A Global Understanding of the Spirit Grace Si-Jun Kim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Yin and Yang of Yoga Tend Toward Emotion, Which Distorts Our Perceptions of Part 2 of a Series by Gyandev Mccord Reality

Newsletter of the Ananda Yoga® Teachers Association Vol. 12 No. 3 • Autumn 2007 I emphasize “potential,” because feeling, too, can be misled. To the degree that we cling tightly to the ego, we The Yin and Yang of Yoga tend toward emotion, which distorts our perceptions of Part 2 of a Series by Gyandev McCord reality. (See Figure 1 on page 2: “The Lens of Feeling.”) ast time, I discussed willpower, the “yang” element of But as we calm, refine and clarify our feeling nature, we Lyoga practice, and offered simple exercises that you get a progressively more accurate picture of reality, until can use to help students develop it. at last we see reality as it truly is. This higher expression Now I’ll do the same for the “yin” of our feeling nature is what I will call “deep feeling.” element: “feeling.” Both Paramhansa In contrast to willpower, which you can develop sim- Yogananda and Swami Kriyananda ply by doing (although as we saw last time, there’s much have long emphasized its impor- more to it than that), feeling is less about doing and tance, and I’ve come to realize from more about awareness. It’s subtle, but not mysterious. It experience how absolutely vital it simply requires increasingly sensitive listening, from a is to success in yoga. It also offers place of increasing calmness, expansiveness, receptivity, and above all, impersonal love. excellent potential content for more Gyandev McCord Let’s now explore how to use Ananda Yoga as a vehicle meaningful yoga classes. Director to refine these qualities, and deepen our feeling capacity. -

DEGLI ANGELI, LA LAVERTY Paul 2012 UK/France/Belgium/Ital 2

N. Titolo Regia Anno Nazione 1 "PARTE" DEGLI ANGELI, LA LAVERTY Paul 2012 UK/France/Belgium/Ital "SE TORNO" - ERNEST PIGNON- 2 COLLETTIVO SIKOZEL 2016 Italy/France ERNEST E LA FIGURA DI PASOLINI 3 ... E FUORI NEVICA SALEMME Vincenzo 2014 Italy 4 ... E FUORI NEVICA SALEMME Vincenzo 2014 Italy 5 ...E L'UOMO CREO' SATANA KRAMER, Stanley 1960 USA 6 ...E ORA PARLIAMO DI KEVIN RAMSAY, Lynne 2011 GB ¡VIVAN LAS ANTIPODAS! - VIVE LES Germany/Argentina/Net 7 KOSSAKOVSKY Victor 2011 ANTIPODES! (VIVA GLI ANTIPODI!) herlands/Chile ¡VIVAN LAS ANTIPODAS! - VIVE LES Germany/Argentina/Net 8 KOSSAKOVSKY Victor 2011 ANTIPODES! (VIVA GLI ANTIPODI!) herlands/Chile 007 - CASINO ROYALE - QUANTUM CAMPBELL, Martin - FORSTER, Marc - 9 2006-2012 USA / GB / Italy OF SOLACE - SKYFALL MENDES, Sam 10 007 - DALLA RUSSIA CON AMORE YOUNG, Terence 1963 USA 11 007 - GOLDENEYE CAMPBELL Martin 1995 UK/USA 12 007 - IL DOMANI NON MUORE MAI SPOTTISWOODE Roger 1997 UK/USA 13 007 - IL MONDO NON BASTA APTED, Michael 1999 USA 14 007 - IL MONDO NON BASTA APTED Michael 1999 UK/USA 15 007 - LA MORTE PUO' ATTENDERE TAMAHORI, Lee 2002 USA 16 007 - LICENZA DI UCCIDERE YOUNG, Terence 1962 USA 17 007 - MAI DIRE MAI KERSHNER, Irvin 1983 GB / USA / Germany 18 007 - MAI DIRE MAI KERSHNER Irvin 1983 UK/USA/West Germany 19 007 - MISSIONE GOLDFINGER HAMILTON, Guy 1964 USA 007 - MOONRAKER - OPERAZIONE 20 GILBERT, Lewis 1979 USA SPAZIO 21 007 - QUANTUM OF SOLACE FORSTER, Marc 2008 USA 22 007 - SOLO PER I TUOI OCCHI GLEN, John 1981 USA 007 - THUNDERBALL - OPERAZIONE 23 YOUNG, Terence 1965 USA TUONO -

Singing Bowl Exercises

MORE PRAISE FOR QUIETING THE MONKEY MIND “Having herself benefitted from their beautiful music, my friend Naomi Judd told me about the husband and wife team of renowned musicians and purveyors of peace, Dudley and Dean Evenson, and shared, ‘you need to know these two and their music.’ So I did just that. I invited Dudley and Dean to perform live for some of my guided group meditations. As I discovered for myself, along with my workshop attendees, their musical gifts are immeasurable. The collaboration was beautiful and raised the experience to a higher level. Meditation with music can truly be transcendent. With their book, Quieting the Monkey Mind, Dudley and Dean transcend traditional teachings and skillfully guide us to disconnect from the noise of life while helping us make a deeper and more peaceful connection with ourselves. Their profound collective wisdom shared within these pages is what we can all benefit from to better understand the benefits of meditation, music, and for achieving the harmony we all seek.” —JOAN BORYSENKO, New York Times bestselling author of Minding the Body, Mending the Mind “Music has been at the core of my being all my life. Amidst my personal and professional busyness of family and career, meditation is a practice that I need and can never have too much of. But, making the time, and getting to that ‘quiet place’ is sometimes a challenge. Well, help has arrived! My longtime friends Dudley and Dean Evenson, renowned musicians and creators of tranquil and peaceful music, have written a beautiful book that teaches meditation and the value of incorporating music into your practice. -

Download the Book from RBSI Archive

About this Document by A. G. Mohan While reading the document please bear in mind the following: 1. The document seems to have been written during the 1930s and early 40s. It contains gems of advice from Krishnamacharya spread over the document. It can help to make the asana practice safe, effective, progressive and prevent injuries. Please read it carefully. 2. The original translation into English seems to have been done by an Indian who is not proficient in English as well as the subject of yoga. For example: a. You may find translations such as ‘catch the feet’ instead of ‘hold the feet’. b. The word ‘kumbhakam’ is generally used in the ancient texts to depict pranayama as well as the holdings of the breath. The original translation is incorrect and inconsistent in some places due to such translation. c. The word ‘angulas’ is translated as inches. Some places it refers to finger width. d. The word ‘secret’ means right methodology. e. ‘Weighing asanas’ meaning ‘weight bearing asanas’. 3. While describing the benefits of yoga practice, asana and pranayama, many ancient Ayurvedic terminologies have been translated into western medical terms such as kidney, liver, intestines, etc. These cannot be taken literally. 4. I have done only very minimal corrections to this original English translation to remove major confusions. I have split the document to make it more meaningful. 5. I used this manuscript as an aid to teaching yoga in the 1970s and 80s. I have clarified doubts in this document personally with Krishnamacharya in the course 2 of my learning and teaching. -

YOGA for Repetitive Use Injury

YOGA For Repetitive Use Injury Stacey Pierce-Talsma DO, MS, RYT [email protected] University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine Objectives • Define yoga and identify the 8 limbs that make up its practice • Discuss the pathophysiology of repetitive use syndromes and understand their healing process • Compare and contrast yogic asana practice to Osteopathic concepts “Words fail to convey • Review yoga literature on the the total value of yoga. application of yoga to chronic repetitive use injuries It has to be experienced.” • Apply and participate in yogic - B.K.S Iyengar pranayama and asana • Introduced to Yoga during my My Personal Holistic Health graduate degree at Western Michigan University Journey as a • Became a regular YOGI practioner several years later • Completed 200 hr YTT Course at Well Heart Yoga • Have been implementing yogic concepts into my NMM/OMM specialty practice • Real connection between yoga and Osteopathic practice as a link to mind body and spirit Introduction to Yoga Yoga for Every Body! 5 Reasons for starting 15 million Americans yoga (1) • practicing yoga more than 3 times a week in 2003 • Flexibility 2012 study- 20.4 million Americans (1) • General conditioning • practice yoga- increase of 29 percent! • Stress relief • Spend an average of $10.3 Billion a year on yoga • Overall health classes and products • Physical fitness • 8.7 percent of U.S Adults • 44.4% of non practioners are “interested in trying yoga” • 82.2% of women, 17.8% men • 38.4% one year or less, 28.9% 1-3 years, 32.7% 3 years or longer • 44.8% beginners, 39.6% intermediate, 15.6% expert/advanced (1) “Yoga in America Market study” 2012- Yoga Journal What is Yoga? • “To Yoke”- Union of the mind, body, and spirit • A “systematic technology to improve the body, understand the mind, and free the spirit” • A collection of methods to attain Samadhi • Sanskrit word for HEALTH • SVASTHA • “Established in the self” • “The light that yoga sheds on Life is something special. -

Required and Recommended Reading List 2018

Required & Recommended Reading List Required and Recommended Reading List Here is your required and suggested reading list. There are many options to choose from. Delve into what interests you, and you’ll find as you evolve, different books and different authors, will involve you! You have brains in your head. You have feet in your shoes. You can steer yourself any direction you choose. You're on your own. And you know what you know. And YOU are the one who'll decide where to go. -- Dr. Seuss Cat Kabira – [email protected] – www.catkabira.com Required & Recommended Reading List Here is your required and suggested reading list. There are many options to choose from. Delve into what interests you, and you’ll find as you evolve, different books and different authors, will involve you! Required Reading: From the following three categories, select two books (they must be from different categories) and then write a 250 word minimum reflection on what you have read. The categories to choose from are: • Yoga Philosophy and Lifestyle • Introspection and Meditation • Energy If you choose to do so, you can replace one of the reading categories with viewing one of the films from the category below and writing your reflection on that. If you choose to do this, you will need to also read one book and submit the reflection as well. *Please note that The Four Agreements is required reading before the course and does not count toward your writing reflection. Please also purchase (via e-book or hard copy) a copy of the following and bring it with you to the training: The Bhagavad Gita: A Walkthrough for Westerners by Jack Hawley. -

YOGANANDA with Personal Reflections & Reminiscences

YOGANANDA WITH PERSONAL REFLECTIONS & REMINISCENCES A Biography swami kriyananda 2 PRAISE FOR Paramhansa Yogananda, A Biography 2 “ This new biography of Paramhansa Yogananda will pave the path to perfection in the spiritual journey of each individual. It is a masterpiece that serves as a guide in daily life. Through the stories of his life and the unfolding of his destiny, Yogananda’s life story will inspire the reader and flower a spiritual awakening in every heart.” —Vasant Lad, BAM&S, MASc, Ayurvedic Physician, author of Ayurveda: Science of Self-Healing, Textbook of Ayurveda series, and more “ Through this biography of Paramhansa Yogananda, people will discover their divine nature and potential.” —Bikram Choudhury, Founder of Bikram’s Yoga College of India, author of Bikram Yoga “ A deeply insightful look into the life of one of the greatest spiritual figures of our time, by one of his most accomplished, yet last-remaining living disciples. Like the life it depicts, this book is a gem!” —Walter Cruttenden, author of Lost Star of Myth and Time “ Swami Kriyananda’s biography is a welcome addition to the growing literature on Paramhansa Yogananda. Yogananda was a true seer and indeed, his words ‘shall not die.’” —Amit Goswami, PhD, quantum physicist and author of The Self-Aware Universe, Creative Evolution, and How Quantum Activism can Save Civilization “ In this wonderful new work, we are treated to an intimate portrait of Yogananda’s quick wit and profound wisdom, his challenges and his triumphs. We see his indomitable spirit dealing with shattering betrayals and his perseverance in his goal of establishing a spiritual mission that has enriched the world. -

Pricelist 2016 Books and Other Media 1 / 4 Orders Can Be Placed Through the Website, for More Information: Jan J. R. Toussaint

Pricelist 2016 Books and other media 1 / 4 Orders can be placed through the website, for more information: Jan J. R. Toussaint, In de Watermolen 30, 1115 GC Duivendrecht Telephone: 020-4160316 - Mailto: [email protected] Sales prices in € (EURO) Titles (highlighted if new/price changed) Excl. BTW BTW Incl. BTW Books A Class After A Class 4,72 0,28 5,00 A Gem For Women 14,15 0,85 15,00 A Matter Of Health 45,28 2,72 48,00 Alpha and Omega Of Trikonasana 8,49 0,51 9,00 Art Of Yoga 14,15 0,85 15,00 Asta Dala-1 16,98 1,02 18,00 Asta Dala-2 16,98 1,02 18,00 Asta Dala-3 16,98 1,02 18,00 Asta Dala-4 16,98 1,02 18,00 Asta Dala-5 16,98 1,02 18,00 Asta Dala-6 16,98 1,02 18,00 Asta Dala-7 16,98 1,02 18,00 Asta Dala-8 16,98 1,02 18,00 Basic Guidelines For Teachers Of Yoga 8,49 0,51 9,00 Chitta Vijanyana of Yogasanas 4,72 0,28 5,00 Discourses on YOG 16,98 1,02 18,00 Fundamentals of Patanjalí Philosophy 13,21 0,79 14,00 Growing Young 5,66 0,34 6,00 Guruji Uvacha 8,49 0,51 9,00 Illustrated Light On Yoga 11,32 0,68 12,00 Iyengar - His Life and Works 14,15 0,85 15,00 Light on Astanga Yoga 10,38 0,62 11,00 Light on Life 14,15 0,85 15,00 Light On Pranayama 13,21 0,79 14,00 Light On Yoga 16,04 0,96 17,00 Light On Yoga Sutras Of Patanjali 13,21 0,79 14,00 Light On Yoga Sutras (US edition) 16,04 0,96 17,00 Organology and sensology in Yogashastra 5,66 0,34 6,00 Prashant Uvacha 15,09 0,91 16,00 Prashantji's Yogasanas and Adhyyamatik science 5,66 0,34 6,00 Tree Of Yoga 10,38 0,62 11,00 Understanding Yoga Through Body Knowledge 11,32 0,68 12,00 Yaugika Manas 7,55 0,45 8,00 Yoga als Levenskunst (paperback editie) 26,37 1,58 27,95 Yoga And The New Millenium 7,55 0,45 8,00 Yoga Dipika 27,83 1,67 29,50 Pricelist 2016 Books and other media 2 / 4 Sales prices in € (EURO) Titles (highlighted if new/price changed) Excl. -

KRIYANANDA As We Have Known Him SWAMI KRIYANANDA As We Have Known Him

SWAMI KRIYANANDA As We Have Known Him SWAMI KRIYANANDA As We Have Known Him Asha Praver C O N T E N T S Introduction 9 15 Copyright © 2006 Hansa Trust 1. Moments of Truth All rights reserved Library of Congree Cataloging-in-Publication Data 2. God Alone 59 Praver, Asha. Swami Kriyananda - As We Knew Him p. cm. 3. Divine Friend 103 Includes bibliographical references & Teacher ISBN: 978-156589-220-0 1. alsdkajsdfòkljd 2. alkdsjfalsdkfjasdlkj 3. alsdkjfadslfkjsdlfkj 173 R155.F36Jdkdkf 2006 610’.92 - dc34 4. From Joy I Came [B] 2000000000 183 Printed in Canada OR USA 5. First Impressions 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 6. In Service to His Guru 225 Design by Tejindra Scott Tully Thanks to all the photographers, known and unknown, who have so lovingly contributed to this book. 7. For Joy I Live 285 8. Through All Trials 331 I Sing Thy Name Crystal Clarity Publishers 14618 Tyler Foote Road Nevada City, CA 95959 USA 9. Grace 399 Tel: 800.424.1055 or 530.478.7600 [email protected] email: www.crystalclarity.com 10. In Sacred Joy I Melt 439 I N T R O D U C T I O N Vivid in My Heart The first time I saw Swami Kriyananda was in a tent set up behind the Beta Chi fraternity house on the campus of Stanford University, in Palo Alto, California. It was late November 1969. He was in his early forties. I was twenty-two years old. Usually the tent served as an expanded venue for the parties for which the fraternity was famous. -

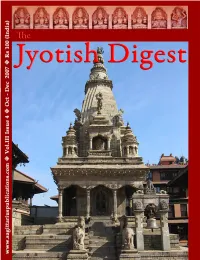

2007 04 Oct-Dec

Th e Jyotish Digest Volume III Issue 4 Quarter Oct-Dec, 2007 Contents Released Nov 1, 2007 2 Letters Editor Pt. Sanjay Rath Editorial office 4 The Jyotish News 15B, Gangaram Hospital Road, New Delhi -110060, India E-mail: [email protected] 12 The Präëapada Lagna Sanjay Rath Book Review Sarbani Rath 22 Parasara’s Drigdasa PVR Narasimha Rao E-mail: [email protected] Layout & Design Sanjay Rath 28 Ratnas – Divine Potencies Swee Chan Cover Photo Vatsala Durga Temple 33 Savitur Aditya, William Shakespeare & Bhaktapur, Nepal Magic Power of Words Steven Hubball Subscription & Membership Mihir Guha Roy 15 B Gangaram Hospital Road, New Delhi 110060, India 37 A Jyotish Critique of the Works of [email protected] P.G.Wodehouse Anurag Sharma Web pages http://sagittariuspublications.com 41 Nakñatra Devatäs Part-II Freedom Cole http://srijagannath.org 49 Vastu astra Niranjan Babu Copyright © The Jyotish Digest. All rights reserved. Individual articles are copyrighted by 54 Read Charts: Raja Yoga Visti Larsen authors after one year of publication. Price 61 Käla Chakra-Introduction Sarbani Rath Rs 100, US$ 15 70 Sohamsa.com RNI No. DELENG 14534/29/1/2004-TC Editor: Sanjay Rath 72 Astrologers Directory Published & Printed by Mihir Guha Roy, Owned and Edited by Sanjay Rath, 15B Gangaram Hospital Road, New Delhi 110060 Meditation and printed at Cirrus Graphics, 261 Phase-I, Naraina Indl. Area, New Delhi 110028 kale v;Rtu pjRNy> käle varñatu parjanyaù JJD0704.inddD0704.indd 1 117-12-20127-12-2012 110:57:420:57:42 letters ` Letters Curse in Badhaka House in its new avatar SJC (Sri Jagannath Center), 1. -

Interfaith Companion Guide

The Companion Letter from Executive Director, Janet Seckel-Cerrotti The mission of FriendshipWorks has creating meaningful intergenerational remained unchanged during the enormous friendships. In a time so full of challenge, the hardships experienced by older adults as a richness of our spritual traditions and result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our communities still provides us with hope and country’s response, sometimes lacking, other optimism for a future where older adults are times inspiring and humbling, has made me treated with the dignity and respect they reflect on something Rabbi Abraham Joshua deserve. Heschel once said: In this way, The Companion provides a venue “A test of a people is how it behaves for intergenerational, interreligious reflections toward the old...the true gold mines of a on faith and aging. It is our hope that the culture.” contents of this newsletter will bring you a sense of spiritual companionship while we all continue The virus’ disproportionate toll on our elders to adapt to physical distancing measures that has made our mission to reduce social may keep us from our churches, mosques, isolation, enhance the quality of life, and temples, meditation groups and prayer preserve the dignity of older adults throughout meetings. Greater Boston ever more urgent and necessary. Since our inception in 1984, when We at FriendshipWorks have been heartened by we were known as MATCH-UP Interfaith the incredible ongoing work of our volunteers, Volunteers, a key partner in this work has the resiliency of our elders, and the been our local religious communities and contributions of our religious partners. -

A Brief Guide to Meditation Excerpts from Awaken to Superconsciousness

A Brief Guide to Meditation Excerpts from Awaken to Superconsciousness Swami Kriyananda (J. Donald Walters) Crystal Clarity Publishers, Nevada City, CA 95959 Copyright © 2000 by Hansa Trust All rights reserved The material in this document is excerpted from Awaken to Superconsciousness: How to Use Meditation for Inner Peace, Intuitive Guidance, and Greater Awareness by Swami Kriyananda Awaken to Superconsciousness was originally published as Superconsciousness: A Guide to Meditation Crystal Clarity Publishers www.CrystalClarity.com 800-424-1055 [email protected] A Brief Guide to Meditation 1 Contents What Is Meditation? .....................................................................3 Asana: Right Posture .....................................................................4 Where to Concentrate ...................................................................5 When to Meditate ........................................................................5 Meditation Exercise: Expansion of Light....................................................6 About the Author .......................................................................8 Further Exploration .....................................................................9 A Brief Guide to Meditation 2 What Is Meditation? began meditating nearly fifty years ago, in 1948. Since then I haven’t, to the best of my recollection, missed I a single day of practice. No stern-minded self-discipline was needed to keep me regular. Meditation is sim- ply the most meaningful activity in