Women's Archives and Women's History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Matriarchal Traditions on the Advancement of Ashanti Women in Ghana Karen Mcgee

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Listening to the Voices: Multi-ethnic Women in School of Education Education 2015 The mpI act of Matriarchal Traditions on the Advancement of Ashanti Women in Ghana Karen McGee Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/listening_to_the_voices Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation McGee, Karen (2015). The mpI act of Matriarchal Traditions on the Advancement of Ashanti Women in Ghana. In Betty Taylor (Eds.), Listening to the Voices: Multi-ethnic Women in Education (p. 1-10). San Francisco, CA: University of San Francisco. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Listening to the Voices: Multi-ethnic Women in Education by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Impact of Matriarchal Traditions on the Advancement of Ashanti Women in Ghana Karen McGee What is the impact of a matriarchal tradition and the tradition of an African queenmothership on the ability of African women to advance in political, educational, and economic spheres in their countries? The Ashanti tribe of the Man people is the largest tribe in Ghana; it is a matrilineal society. A description of the precolonial matriarchal tradition among the Ashanti people of Ghana, an analysis of how the matriarchal concept has evolved in more contemporary governments and political situations in Ghana, and an analysis of the status of women in modern Ghana may provide some insight into the impact of the queenmothership concept. -

The Concept of "Woman": Feminism After the Essentialism Critique

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Philosophy Theses Department of Philosophy 4-21-2008 The Concept of "Woman": Feminism after the Essentialism Critique Katherine Nicole Fulfer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_theses Recommended Citation Fulfer, Katherine Nicole, "The Concept of "Woman": Feminism after the Essentialism Critique." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_theses/36 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Philosophy at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CONCEPT OF “WOMAN”: FEMINISM AFTER THE ESSENTIALISM CRITIQUE by KATHERINE N. FULFER Under the direction of Christie J. Hartley and Andrew I. Cohen ABSTRACT Although feminists resist accounts that define women as having certain features that are essential to their being women, feminists are also guilty of giving essentialist definitions. Because women are extremely diverse in their experiences, the essentialist critics question whether a universal (non-essentialist) account of women can be given. I argue that it is possible to formulate a valuable category of woman, despite potential essentialist challenges. Even with diversity among women, women are oppressed as women by patriarchal structures such as rape, pornography, and sexual harassment that regulate women’s sexuality and construct women as beings whose main role is to service men’s needs. INDEX WORDS: Feminism, Essentialism, Essentialist critique, Rape, Pornography, Sexual harassment, Oppression THE CONCEPT OF “WOMAN”: FEMINISM AFTER THE ESSENTIALISM CRITIQUE by KATHERINE N. -

Women and Conflict in Afghanistan

Women and Conflict in Afghanistan Asia Report N°252 | 14 October 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Decades of Civil War ........................................................................................................ 2 A. The Anti-Soviet Jihad ................................................................................................ 2 B. The Taliban’s Gender Apartheid ................................................................................ 4 III. Post-2001 Gains ............................................................................................................... 7 A. Constitutional Guarantees and Electoral Rights ....................................................... 7 B. Institutional Equality, Protection and Development ................................................ 9 IV. Two Steps Forward, One Step Back ................................................................................. 13 A. Political Empowerment and Electoral Gains............................................................ -

Women in Afghanistan Fact Sheet

WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN AFGHANISTAN BACKGROUND INFORMATION Since the fall of the Taliban in 2001 progress has been made to protect the rights of women in Afghanistan but, with the withdrawal of international troops planned for the end of 2014, insecurity could increase and Amnesty International is very concerned that women’s rights are at risk. KEY FACTS The Taliban ruled Afghanistan from 1996 – 2001 Afghan women right’s activists demonstrating Under the Taliban, women and girls were: • Banned from going to school or studying. • Banned from working. An Afghan woman wearing a burqa votes in Kabul 2004 • Banned from leaving the house without a male chaperone. • Banned from showing their skin in public. • Banned from accessing healthcare delivered by men (as women weren’t allowed to work this meant healthcare was not available to women). • Banned from being involved in politics or speaking publicly. If these laws were disobeyed, punishments were harsh. A woman could be flogged for showing an inch or two of skin under her full-body burqa, beaten for attempting to study, stoned to death if she was found guilty of adultery. After the fall of the Taliban in 2001 women and girls in Afghanistan gradually began to claim their basic human AMNESTY’S POSITION rights: many schools opened their doors to girls, women Our campaign on Afghan women’s rights is known as went back to work and voted in local and national ‘Protect the Progress’. elections. Some entered politics even though it was still very risky. We demand that the UK government: • Improves their support and protection for those It’s now been over ten years since the Taliban were women who work to defend human rights. -

Erotica Menu: Ideas for Alternatives to Traditional

OHSU Program in Vulvar Health Erotica Menu Suggestions for Exploring Intimacy Without Pain Vulvar and vulvovaginal pain affect each woman and her sexuality differently. Some of you have not been able to feel or behave sexually for some time, and you may fear that you have lost your ability to do so. Part of your recovery from your pain is to (re)build your sexual and relationship confidence. We therefore encourage you to consider the kinds of relationship activities and ideas below as part of your treatment for your vulvar symptoms. Vaginal and penetrative intercourse is only one way of being sexual. And, although it is the behavior that most of us consider to be “having sex,” it is often not the most sexually gratifying activity for women. When you have vulvar pain, intercourse can become impossible. Although facing this can be difficult, it can also be an excellent opportunity for women and couples to find out what else they might like to do together that can help them to restore and/or maintain sexual and physical intimacy in their relationship. And for those of you not in relationships, it can be a time to learn a lot about what your own body enjoys and desires. In the spirit of exploration and pleasure enhancement for you and your partner (if you have one), we offer the following “menu.” Some of these activities are genitally/sexually focused, others are not. Please use them as guides and experiments. The list is not exhaustive and we encourage you to use the books, websites and other resources contained in these suggestions in order to further your own sexual research. -

How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F

Hofstra Law Review Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 5 2004 How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F. Moran Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Moran, Rachel F. (2004) "How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 33: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol33/iss1/5 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moran: How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman HOW SECOND-WAVE FEMINISM FORGOT THE SINGLE WOMAN Rachel F. Moran* I cannot imagine a feminist evolution leading to radicalchange in the private/politicalrealm of gender that is not rooted in the conviction that all women's lives are important, that the lives of men cannot be understoodby burying the lives of women; and that to make visible the full meaning of women's experience, to reinterpretknowledge in terms of that experience, is now the most important task of thinking.1 America has always been a very married country. From early colonial times until quite recently, rates of marriage in our nation have been high-higher in fact than in Britain and western Europe.2 Only in 1960 did this pattern begin to change as American men and women married later or perhaps not at all.3 Because of the dominance of marriage in this country, permanently single people-whether male or female-have been not just statistical oddities but social conundrums. -

Daoist Connections to Contemporary Feminism in China Dessie Miller [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-19-2017 Celebrating the Feminine: Daoist Connections to Contemporary Feminism in China Dessie Miller [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Feminist Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Dessie, "Celebrating the Feminine: Daoist Connections to Contemporary Feminism in China" (2017). Master's Projects and Capstones. 613. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/613 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. !1 CELEBRATING THE FEMININE: DAOIST CONNECTIONS TO CONTEMPORARY FEMINISM IN CHINA Dessie D. Miller APS 650: MA Capstone Seminar University of San Francisco 16 May 2017 !2 Acknowledgments I wish to present my special thanks to Professor Mark T. Miller (Associate Professor of Systematic Theology and Associate Director of the St. Ignatius Institute), Professor John K. Nelson (Academic Director and Professor of East Asian religions in the Department of Theology and Religious Studies), Mark Mir (Archivist & Resource Coordinator, Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History), Professor David Kim (Associate Professor of Philosophy and Program Director), John Ostermiller (M.A. in Asia Pacific Studies/MAPS Program Peer-Tutor), and my classmates in the MAPS Program at the University of San Francisco for helping me with my research and providing valuable advice. -

Implications of Illicit Rendezvous in Medieval Narrative

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1-1-2018 She is Right to Behave Thus: Implications of Illicit Rendezvous in Medieval Narrative Catherine Albers University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Albers, Catherine, "She is Right to Behave Thus: Implications of Illicit Rendezvous in Medieval Narrative" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1196. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1196 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SHE IS RIGHT TO BEHAVE THUS”: IMPLICATIONS OF ILLICIT RENDEZVOUS IN MEDIEVAL NARRATIVE A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of Mississippi by CATHERINE M. ALBERS May 2018 Copyright Catherine M. Albers 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT While preconceptions of the Middle Ages often rely on assumptions about Christianity and the kind of society that the Catholic Church promoted, the reality is that the historical and literary medieval world is much more complicated. When discussing the issues of sexuality, women, and sexual normativity, these assumptions hinder our ability to accurately analyze the content and reception of medieval literature. This project addresses this gap by positioning itself among the criticism set forth by scholars of four different cultures (Irish, Norse, English, and Italian) to examine the connections between the reception of women who act outside of the boundaries of both their society and our modern expectations of medieval female sexuality. -

Making the Invisible Visible: Gender Microaggressions

UNH ADVANCE INSTITUTIONAL TRANSFORMATION An NSF funded program to improve the climate for UNH faculty through fair and equitable policies, practices and leadership development. Making the Invisible Visible: Gender Microaggressions Imagine these scenarios: You are a member of a faculty search committee hiring an committee member frequently looks at her chest, which makes assistant professor in biology. The committee is just starting a the candidate very uncomfortable. The committee member face-to-face interview with a candidate named Maria Vasquez. seems unaware of her behavior. She has dark hair, dark eyes, and a tan complexion. Most During a meeting of the faculty search committee on which you committee members assume Dr. Vasquez is Latina. One of your are serving, almost every time a female colleague tries to speak, colleagues asks an ice-breaking question, “Where are you from?” she is interrupted by a male colleague. No one says anything Dr. Vasquez responds, “Minneapolis.” Your colleague follows-up when this happens. Finally, your female colleague stops trying with, “No, I mean, where do you come from originally?” to ofer contributions to the discussion. You wonder what she Dr. Vasquez frowns. “Minneapolis,” she repeats with an edge to wanted to say. her voice. An African American man named Alex is a candidate for a A search committee hiring a department chair in environmental tenure-track job in chemistry. During his on-campus interview, science is meeting to discuss the fnal list of candidates, which the chairperson of the search committee is giving him a tour. As includes two men and one women. -

Afghan Women and Girls: Status and Congressional Action

Updated August 18, 2021 Afghan Women and Girls: Status and Congressional Action The status of Afghan women and girls is increasingly 2004 Afghan constitution prohibits discrimination on the precarious in light of the Taliban’s takeover of the country basis of gender and enshrines equal rights between men and in mid-August 2021. Given the Taliban’s views on women. It mandates that at least two women be elected to women’s rights, and entrenched cultural attitudes the lower house of parliament from each of Afghanistan’s (particularly in rural areas), the status of Afghan women 34 provinces, creating a female representation quota of and girls has long been a topic of congressional concern and about 27% in the lower house and 17% in the upper house. action. Concern among some Members of Congress has The Afghan government had also committed to achieving increased in the wake of the drawdown of U.S. military and 30% representation of women in the civil service (around civilian personnel and the Taliban takeover. Reports 27% as of 2019) and increasing the number of women in indicate that the Taliban have re-imposed restrictions on the Afghanistan National Defense and Security Forces women in some areas taken in 2021. In addition to fears for (ANDSF) (just over 2% as of May 2021). the rights, health, and economic wellbeing of Afghan women broadly, some Members’ immediate concerns focus Some recent surveys suggested that traditional, restrictive on evacuation and visa questions, with a longer-term focus views of gender roles and rights, including some views consistent with the Taliban’s former practices, remain on how, if at all, U.S. -

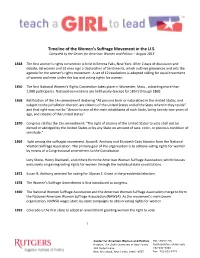

Timeline of the Women's Suffrage Movement in the U.S

Timeline of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the U.S. Compiled by the Center for American Women and Politics – August 2014 1848 The first women's rights convention is held in Seneca Falls, New York. After 2 days of discussion and debate, 68 women and 32 men sign a Declaration of Sentiments, which outlines grievances and sets the agenda for the women's rights movement. A set of 12 resolutions is adopted calling for equal treatment of women and men under the law and voting rights for women. 1850 The first National Women's Rights Convention takes place in Worcester, Mass., attracting more than 1,000 participants. National conventions are held yearly (except for 1857) through 1860. 1868 Ratification of the 14th amendment declaring “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside” and that right may not be “denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States” 1870 Congress ratifies the 15th amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” 1869 Split among the suffragist movement. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton form the National Woman Suffrage Association. The primary goal of the organization is to achieve voting rights for women by means of a Congressional amendment to the Constitution. -

Transfeminist Perspectives in and Beyond Transgender and Gender Studies Seeks to Highlight the Productive and Sometimes Fraught Potential of This Relationship

A. FINN ENKE Introduction Transfeminist Perspectives his book is born of the conviction that feminist studies and transgender studies are intimately connected to one another in their endeavor to T analyze epistemologies and practices that produce gender. Despite this connection, they are far from integrated. Transfeminist Perspectives in and beyond Transgender and Gender Studies seeks to highlight the productive and sometimes fraught potential of this relationship. Feminist, women’s, and gender studies grew partly from Simone de Beauvoir’s observation that “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.”1 Transgender studies extends this founda- tion, emphasizing that there is no natural process by which anyone becomes woman, and also that everyone’s gender is made: Gender, and also sex, are made through complex social and technical manipulations that naturalize some while abjecting others. In this, both feminist and transgender studies acknowledge the mutual imbrications of gender and class formations, dis/abilities, racializations, political economies, incarcerations, nationalisms, migrations and dislocations, and so forth. We share, perhaps, a certain delight and trepidation in the aware- ness that gender is trouble: Gender may trouble every imaginable social relation and fuel every imaginable social hierarchy; it may also threaten to undo itself and us with it, even as gender scholars simultaneously practice, undo, and rein- vest in gender.2 Women’s and gender studies have registered increasing interest in things transgender since the mid-1990s. Scholars have organized conferences on the topic, and numerous feminist journals have published special transgender issues.3 Th is interest has been inspired in part by inquiry into the meanings of gender, bodies, and embodiment, by transnational and cross-cultural studies that address the varied ways in which cultures ascribe gender, and also by insti- tutional practices that circumscribe or broaden the range of gender legibility.