Untangling Relationships Among Terraranan Frogs: a Phylogenomic Approach Based on 2,665 Loci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

Historically, Direct-Developing Frogs of The

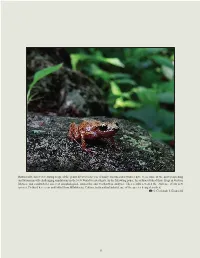

Historically, direct-developing frogs of the genus Eleutherodacylus (Family: Eleutherodactylidae) have been some of the most perplexing and taxonomically challenging amphibians in the New World to investigate. In the following paper, the authors studied these frogs in western Mexico, and conducted a series of morphological, molecular, and vocalization analyses. Their results revealed the existence of six new species. Pictured here is an individual from Ixtlahuacán, Colima, in its natural habitat, one of the species being described. ' © Christoph I. Grünwald 6 Grünwald et al. Six new species of Eleutherodactylus www.mesoamericanherpetology.com www.eaglemountainpublishing.com Version of record: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:3EDC9AB7-94EE-4EAC-89B4-19F5218A593A Six new species of Eleutherodactylus (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae: subgenus Syrrhophus) from Mexico, with a discussion of their systematic relationships and the validity of related species CHRISTOPH I. GRÜNWALD1,2,3,6, JACOBO REYES-VELASCO3,4,6, HECTOR FRANZ-CHÁVEZ3,5,6, KAREN I. 3,6 3,5,6 2,3,6 4 MORALES-FLORES , IVÁN T. AHUMADA-CARRILLO , JASON M. JONES , AND STEPHANE BOISSINOT 1Biencom Real Estate, Carretera Chapala - Jocotepec #57-1, C.P. 45920, Ajijic, Jalisco, Mexico. E-mail: [email protected] (Corresponding author) 2Herpetological Conservation International - Mesoamerica Division, 450 Jolina Way, Encinitas, California 92024, United States. 3Biodiversa A. C., Chapala, Jalisco, Mexico. 4New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. 5Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Carretera a Nogales Km. 15.5. Las Agujas, Nextipac, Zapopan, C.P. 45110, Jalisco, Mexico. 6Herp.mx A.C., Villa de Alvarez, Colima, Mexico. ABSTRACT: We present an analysis of morphological, molecular, and advertisement call data from sampled populations of Eleutherodactylus (subgenus Syrrhophus) from western Mexico and describe six new spe- cies. -

Diptera: Sarcophagidae) in Anuran of Leptodactylidae (Amphibia)

CASO CLÍNICO REVISTA COLOMBIANA DE CIENCIA ANIMAL Rev Colombiana Cienc Anim 2015; 7(2):217-220. FIRST REPORT OF MYIASIS (DIPTERA: SARCOPHAGIDAE) IN ANURAN OF LEPTODACTYLIDAE (AMPHIBIA) PRIMER REGISTRO DE MIASIS (DIPTERA: SARCOPHAGIDAE) EN ANUROS DE LEPTODACTYLIDAE (AMPHIBIA) GERSON AZULIM MÜLLER,1*Dr, CARLOS RODRIGO LEHN,1 M.Sc, ABEL BEMVENUTI,1 M.Sc, CARLOS BRISOLA MARCONDES,2 Dr. 1Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia Farroupilha, Campus Panambi, RS, Brasil. 2 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Departamento de Microbiologia e Parasitologia, Centro de Ciências Biológicas, SC, Brasil. Key words: Abstract Anura, This note is the first report of myiasis caused by Sarcophagidae flies in an anuran of Brazil, Leptodactylidae. The frog, identified asLeptodactylus latrans (Steffen, 1815), was Leptodactylus latrans, collected in Atlantic forest bioma, southern Brazil. The frog had extensive muscle parasitism. damage and orifices in the tegument caused by presence of 21 larvae, identified as Sarcophagidae. Ecological interactions between dipterans and anuran are poorly known. The impact of sarcophagid flies in anuran popuilations requires further study. Palabras Clave: Resumen Anura, Esta nota es el primer registro de ocurrencia de miasis generada por moscas Brasil, Sarcophagidae en anuro de la familia Leptodactylidae. El anfibio, identificado Leptodactylus latrans, como Leptodactylus latrans (Steffen, 1815), fue recolectado en el bioma Mata parasitismo. Atlântica, en el sur de Brasil. La rana presentaba extensas lesiones musculares y orificios en el tegumento generados por la presencia de 21 larvas, identificadas como Sarcophagidae. Las interacciones ecológicas entre insectos dípteros y anuros son poco conocidas. El impacto de las moscas Sarcophagidae en las poblaciones de anuros requiere más estudio. -

Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Publications Plant Health Inspection Service 2012 Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae) Christina A. Olson Utah State University, [email protected] Karen H. Beard Utah State University, [email protected] William C. Pitt National Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Olson, Christina A.; Beard, Karen H.; and Pitt, William C., "Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae)" (2012). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 1174. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/1174 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae)1 Christina A. Olson,2 Karen H. Beard,2,4 and William C. Pitt 3 Abstract: The greenhouse frog, Eleutherodactylus planirostris, is a direct- developing (i.e., no aquatic stage) frog native to Cuba and the Bahamas. It was introduced to Hawai‘i via nursery plants in the early 1990s and then subsequently from Hawai‘i to Guam in 2003. The greenhouse frog is now widespread on five Hawaiian Islands and Guam. -

Froglog95 New Version Draft1.Indd

March 2011 Vol. 95 FrogLogwww.amphibians.org News from the herpetological community The new face of the ASG “Lost” Frogs Red List The global search Updating South comes to an end. Africas Red Where next? Lists. Page 1 FrogLog Vol. 95 | March 2011 | 1 2 | FrogLog Vol. 95 | March 2011 CONTENTS The Sierra Caral of Guatemala a refuge for endemic amphibians page 5 The Search for “Lost” Frogs page 12 Recent diversifi cation in old habitats: Molecules and morphology in the endangered frog, Craugastor uno page 17 Updating the IUCN Red List status of South African amphibians 6 Amphibians on the IUCN Red List: Developments and changes since the Global Amphibian Assessment 7 The forced closure of conservation work on Seychelles Sooglossidae 8 Alien amphibians challenge Darwin’s naturalization hypothesis 9 Is there a decline of amphibian richness in Bellanwila-Attidiya Sanctuary? 10 High prevalence of the amphibian chytrid pathogen in Gabon 11 Breeding-site selection by red-belly toads, Melanophryniscus stelzneri (Anura: Bufonidae), in Sierras of Córdoba, Argentina 11 Upcoming meetings 20 | Recent Publications 20 | Internships & Jobs 23 Funding Opportunities 22 | Author Instructions 24 | Current Authors 25 FrogLog Vol. 95 | March 2011 | 3 FrogLog Editorial elcome to the new-look FrogLog. It has been a busy few months Wfor the ASG! We have redesigned the look and feel of FrogLog ASG & EDITORIAL COMMITTEE along with our other media tools to better serve the needs of the ASG community. We hope that FrogLog will become a regular addition to James P. Collins your reading and a platform for sharing research, conservation stories, events, and opportunities. -

Amphibia: Anura: Eleutherodactylidae), from Eastern Cuba

124 SOLENODON 12: 124-135, 2015 Another new cryptic frog related to Eleutherodactylus varleyi Dunn (Amphibia: Anura: Eleutherodactylidae), from eastern Cuba Luis M. DÍAZ* and S. Blair HEDGES** *Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Cuba, Obispo #61, Esquina Oficios, Plaza de Armas, Habana Vieja, CP 10100, Cuba. [email protected] **Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Laboratory, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802-530, USA. [email protected] ABSTRacT. A new cryptic frog, Eleutherodactylus beguei sp. nov., is described from the pine forests of La Munición, Yateras, Guantánamo Province, Cuba. It is sympatric with E. feichtin- geri, another recently described grass frog closely related to E. varleyi, but differs in morphol- ogy, vocalization and DNA sequences of the mitochondrial Cyt-b gene. One female of the new species was found vocalizing in response to a calling male, a behavior that is still poorly documented in anurans. Same male and female were found in axillary amplexus and sur- rounded by 9 eggs (3.5–3.7 mm in diameter) 5 hours after being isolated in a small container. Key words: Amphibia, Anura, Eleutherodactylidae, Eleutherodactylus, new species, Terrarana, Euhyas, West Indies, Guantánamo, female reciprocation calls, eggs. INtrODUCtION After a recent review of the geographic variation of the Cuban Grass Frog Eleutherodactylus varleyi Dunn, Díaz et al. (2012) described E. feichtingeri, a cryptic species widely distributed in central and eastern Cuba. the two species differ primarily in tympanum size, supratympanic stripe pattern, and advertisement calls. Species recognition was also supported by genetic and cytogenetic data. One of the authors (SBH) conducted DNA sequence analyses that confirmed the existence of two species at La Munición, Humboldt National Park. -

Seasonal Distribution and Circadian Activity in the Troglophile Long-Footed Robber Frog, Eleutherodactylus Longipes (Anura: Brac

A. Espino del Castillo, G. Castan˜o-Meneses, M.J. Da´vila-Montes, M. Miranda-Anaya, J.B. Morales-Malacara, and R. Paredes-Leo´n – Seasonal distribution and circadian activity in the troglophile long-footed robber frog, Eleutherodactylus longipes (Anura: Brachycephalidae) at Los Riscos Cave, Quere´taro, Mexico: Field and laboratory studies. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, v. 71, no. 1, p. 24–31. SEASONAL DISTRIBUTION AND CIRCADIAN ACTIVITY IN THE TROGLOPHILE LONG-FOOTED ROBBER FROG, ELEUTHERODACTYLUS LONGIPES (ANURA: BRACHYCEPHALIDAE) AT LOS RISCOS CAVE, QUERE´ TARO, MEXICO: FIELD AND LABORATORY STUDIES ADRIANA ESPINO DEL CASTILLO1,GABRIELA CASTAN˜ O-MENESES2,4,MAYRA J. DA´ VILA-MONTES1,3, MANUEL MIRANDA-ANAYA3,JUAN B. MORALES-MALACARA1,4,6, AND RICARDO PAREDES-LEO´ N5 Abstract: Los Riscos Cave belongs to the El Abra limestone and its geographical location is in the Sierra Gorda in the State of Quere´taro, Mexico. The cave has a high faunal diversity that includes arthropods and some vertebrates, such as vampire bats and anurans, and includes the robber frog Eleutherodactylus longipes (Baird, 1859). The abundance of the robber frog changes non-randomly between dry and rainy seasons and is related to the search for humid conditions inside the cave. In addition, the robber frog was located in areas where some scattered light may influence its dispersion inside the cave; and therefore, its activity. Frogs displayed spontaneous circadian rhythms of locomotor activity from the first days of the experimental observation in constant darkness. The average period of circadian rhythms was 24.85 6 0.93 h indicating, in isolated conditions, a diurnal activity. -

A Review of Chemical Defense in Poison Frogs (Dendrobatidae): Ecology, Pharmacokinetics, and Autoresistance

Chapter 21 A Review of Chemical Defense in Poison Frogs (Dendrobatidae): Ecology, Pharmacokinetics, and Autoresistance Juan C. Santos , Rebecca D. Tarvin , and Lauren A. O’Connell 21.1 Introduction Chemical defense has evolved multiple times in nearly every major group of life, from snakes and insects to bacteria and plants (Mebs 2002 ). However, among land vertebrates, chemical defenses are restricted to a few monophyletic groups (i.e., clades). Most of these are amphibians and snakes, but a few rare origins (e.g., Pitohui birds) have stimulated research on acquired chemical defenses (Dumbacher et al. 1992 ). Selective pressures that lead to defense are usually associated with an organ- ism’s limited ability to escape predation or conspicuous behaviors and phenotypes that increase detectability by predators (e.g., diurnality or mating calls) (Speed and Ruxton 2005 ). Defended organisms frequently evolve warning signals to advertise their defense, a phenomenon known as aposematism (Mappes et al. 2005 ). Warning signals such as conspicuous coloration unambiguously inform predators that there will be a substantial cost if they proceed with attack or consumption of the defended prey (Mappes et al. 2005 ). However, aposematism is likely more complex than the simple pairing of signal and defense, encompassing a series of traits (i.e., the apose- matic syndrome) that alter morphology, physiology, and behavior (Mappes and J. C. Santos (*) Department of Zoology, Biodiversity Research Centre , University of British Columbia , #4200-6270 University Blvd , Vancouver , BC , Canada , V6T 1Z4 e-mail: [email protected] R. D. Tarvin University of Texas at Austin , 2415 Speedway Stop C0990 , Austin , TX 78712 , USA e-mail: [email protected] L. -

Factors Influencing the Behavior and Distribution of Spea Intermontana in Eastern Washington State

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Spring 2018 Life in the Dirt: Factors Influencing the Behavior and Distribution of Spea Intermontana in Eastern Washington State Corey Brumbaugh Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Desert Ecology Commons, Other Animal Sciences Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Brumbaugh, Corey, "Life in the Dirt: Factors Influencing the Behavior and Distribution of Spea Intermontana in Eastern Washington State" (2018). All Master's Theses. 930. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/930 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIFE IN THE DIRT: FACTORS INFLUENCING THE BEHAVIOR AND DISTRIBUTION OF SPEA INTERMONTANA IN EASTERN WASHINGTON STATE __________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University ___________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Biological Sciences ___________________________________ by Corey Jacob Brumbaugh June 2018 i CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Corey Jacob Brumbaugh Candidate for the degree of Master of Science APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. R. Steven Wagner, Committee Chair ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Wayne Quirk ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Robert E. Weaver ______________ _________________________________________ Dean of Graduate Studies ii ABSTRACT I divided my thesis into two major studies focusing on the Great Basin Spadefoot Toad, Spea intermontana, at the Beverley Dunes (Beverley, WA). -

Contact Toxicities of Anuran Skin Alkaloids Against the Fire Ant (Solenopsis Invicta)

Naturwissenschaften (2013) 100:185–192 DOI 10.1007/s00114-013-1010-0 ORIGINAL PAPER Contact toxicities of anuran skin alkaloids against the fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) Paul J. Weldon & Yasmin J. Cardoza & Robert K. Vander Meer & W. Clint Hoffmann & John W. Daly & Thomas F. Spande Received: 19 July 2012 /Revised: 4 January 2013 /Accepted: 7 January 2013 /Published online: 23 January 2013 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (outside the USA) 2013 Abstract Nearly 500 alkaloids, representing over 20 struc- estimated the cutaneous concentrations of several com- tural classes, have been identified from the skin of neotrop- pounds based on their reported recoveries from skin extracts ical poison frogs (Dendrobatidae). These cutaneous of free-ranging frogs and our measurements of the skin compounds, which are derived from arthropod prey of the surface areas of museum specimens. Pumiliotoxin 251D frogs, generally are believed to deter predators. We tested exhibited contact toxicity below its estimated cutaneous the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) for toxicosis concentration in the Ecuadorian frog, Epipedobates antho- following contact with 20 alkaloids (12 structural classes) nyi, an observation consistent with the hypothesized role identified from dendrobatids or other anurans. Individual of this compound in anuran chemical defense. Our results ants forced to contact the dried residues of 13 compounds and those of a previous study of mosquitoes indicate that exhibited convulsions and/or reduced ambulation. We some anuran skin compounds function defensively as contact toxins against arthropods, permeating their exoskeleton. Communicated by: Sven Thatje . John W. Daly deceased 5 March, 2008 Keywords Alkaloid Allomone Ant Defense Frog Toxicity P. -

Zootaxa, a New Species of Ischnocnema from Highlands of the Atlantic Forest

Zootaxa 2617: 55–65 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new species of Ischnocnema from highlands of the Atlantic Forest, Southeastern Brazil (Terrarana, Brachycephalidae) ITAMAR A. MARTINS1,3 & CÉLIO F. B. HADDAD2 1Laboratório de Zoologia – Instituto Básico de Biociências, Universidade de Taubaté – UNITAU, 12030-180 Taubaté, SP, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] 2Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista, 13506-900 Rio Claro, SP, Brasil 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new species of Ischnocnema is described from Serra da Mantiqueira, Municipality of Campos do Jordão, State of São Paulo, Brazil. The new species is a member of the Ischnocnema lactea Species Series. The new species differs from other species in the Ischnocnema lactea Species Series by its small size, snout sub-elliptical in dorsal view and acuminate-rounded in lateral view, and advertisement call. Descriptions of the dorsal coloration, advertisement call, and natural history are presented. Key words: New species; Ischnocnema; Brachycephalidae; Southeastern Brazil Introduction The taxon Terrarana contains four families: Brachycephalidae, Eleutherodactylidae, Craugastoridae, and Strabomantidae (Hedges et al., 2008). The distribution of Terrarana ranges from Texas in the USA southward throughout Mexico, Central America, and the West Indies, and the tropical and subtropical areas of South America to northern Argentina (Hedges et al., 2008). The family Brachycephalidae contains two genera: Brachycephalus with 12 species and Ischnocnema with 32 species (Alves et al., 2009; Targino et al., 2009; Frost, 2010). The family is distributed from north to southern Atlantic forest and central Brazil and in most of southeastern Brazil and northern Argentina (Hedges et al., 2008; Frost, 2010). -

3Systematics and Diversity of Extant Amphibians

Systematics and Diversity of 3 Extant Amphibians he three extant lissamphibian lineages (hereafter amples of classic systematics papers. We present widely referred to by the more common term amphibians) used common names of groups in addition to scientifi c Tare descendants of a common ancestor that lived names, noting also that herpetologists colloquially refer during (or soon after) the Late Carboniferous. Since the to most clades by their scientifi c name (e.g., ranids, am- three lineages diverged, each has evolved unique fea- bystomatids, typhlonectids). tures that defi ne the group; however, salamanders, frogs, A total of 7,303 species of amphibians are recognized and caecelians also share many traits that are evidence and new species—primarily tropical frogs and salaman- of their common ancestry. Two of the most defi nitive of ders—continue to be described. Frogs are far more di- these traits are: verse than salamanders and caecelians combined; more than 6,400 (~88%) of extant amphibian species are frogs, 1. Nearly all amphibians have complex life histories. almost 25% of which have been described in the past Most species undergo metamorphosis from an 15 years. Salamanders comprise more than 660 species, aquatic larva to a terrestrial adult, and even spe- and there are 200 species of caecilians. Amphibian diver- cies that lay terrestrial eggs require moist nest sity is not evenly distributed within families. For example, sites to prevent desiccation. Thus, regardless of more than 65% of extant salamanders are in the family the habitat of the adult, all species of amphibians Plethodontidae, and more than 50% of all frogs are in just are fundamentally tied to water.