The Corvette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January Cover.Indd

Aircraft Detail In Action Armor Detail In Action Available in Both Hard & Softcover! NEW F8F Bearcat Detail in Action NEW M19-M20 Tank Transporter Detail in Action Doyle. The Grumman F8F Bearcat represents the pinnacle of US carrier-borne piston-engine fighter design. Marrying Doyle. Collectively known as the M19 Heavy Tank Transporter, this truck and trailer combination was conceived at the a compact, lightweight airframe with a powerful 18-cylinder Pratt & Whitney Double Wasp radial engine churning behest of British in 1941, and was later used by the United States Army as well. The prime mover for the combination out more than 2,000 horsepower produced an aircraft intended to be an interceptor that could operate from the was the Diamond T model 980 or 981 12-ton truck, known as the M20, while the 45-ton capacity full trailer it smallest escort carriers. While the Bearcat prototype first took to the air in August 1944, and the first squadron towed was designated the M9. The combination saw widespread use during World War II, and well into the postwar equipped with the new fighters was operational in May 1945, the war ended before the Bearcat actually saw combat years. Explores the development, use, and details of these wartime workhorses. Illustrated with 222 photographs (64 in World War II. The type would ultimately see combat in the First Indochina War. Visually chronicles this diminutive black-and-white vintage photographs in conjunction with 158 detailed full-color photos of immaculately preserved fighter with ample images and captures the nuances of this famed warbird. -

Off They Go, Intothesky

B2 PHOTO GALLERY Morethings to do this weekend exploreLI newsday.com/events 1 IN eL nowonline Below, the U.S. Navy Blue Explor Angels perform at the air show summereats overJones Beach in 2012. ON THE COVER: Our food staff came TheBreitling Jet Team, with up with a bucket list pilots from the French air of iconic foods that force, soarsatlastyear’s show. cry out to be hunted down as the mercury rises. From Long OBO LC Island’s juiciest fried BA chicken to its plump- TO est lobster rolls, must- CRIS have icecream and AN JU more, the quest is on. UltimateLIfoodie list: newsday.com/lifestyle holidaysales To kick off the unoffical startof Offtheygo, summer,retailers offer deals and discounts on clothing and appliances around Memorial Day weekend. Here’s a intothe sky rundown of where CK youcan save. TO IS BY JIM MERRITT BethpageAir Show Corps. Currentlycelebrating Memorial Daysales 2016: newsday.com/lifestyle Special to Newsday their 70th anniversary (1946), the Blue Angels have per- or manyofthe 300,000 brings Blue Angels, formed formorethan 484 spectators expected at million fans. grillingfavorites Jones Beach Memorial Golden Knights and AIRCRAFT Modified Boeing F Dayweekend, the F/A-18 Hornets and the Lock- BethpageAir Showis moretoJones Beach heed Martin C-130Hercules, Whether you’re another chancetospreada the latteraffectionatelyknown hosting abarbecue blanket on the sand and be as “Fat Albert.” or heading to a awestruck by the barrel rolls, will open the show, flying HOME BASE Pensacola, Memorial Day loops and diamond formations single- and twin-engine Piper Florida of those daredevil U.S. -

Airpilotdec 2017 ISSUE 24

AIR PILOT DEC 2017:AIR PILOT MASTER 29/11/17 09:25 Page 1 AirPilot DEC 2017 ISSUE 24 AIR PILOT DEC 2017:AIR PILOT MASTER 29/11/17 09:25 Page 2 Diary DECEMBER 2017 7th General Purposes & Finance Committee Cobham House AIR PILOT 14th Carol Service St. Michaels, Cornhill THE HONOURABLE COMPANY OF JANUARY 2018 AIR PILOTS 10th AST/APT meeting Dowgate Hill House incorporating 16th Air Pilots Benevolent Fund AGM RAF Club Air Navigators 18th General Purposes & Finance Committee Dowgate Hill House 18th Court & Election Dinner Cutlers’ Hall PATRON: His Royal Highness FEBRUARY 2018 The Prince Philip 7th Pilot Aptitude Testing RAF Cranwell Duke of Edinburgh KG KT 8th General Purposes & Finance Committee Dowgate Hill House 20th Luncheon Club RAF Club GRAND MASTER: His Royal Highness The Prince Andrew Duke of York KG GCVO MASTER: VISITS PROGRAMME Captain C J Spurrier Please see the flyers accompanying this issue of Air Pilot or contact Liveryman David Curgenven at [email protected]. CLERK: These flyers can also be downloaded from the Company's website. Paul J Tacon BA FCIS Please check on the Company website for visits that are to be confirmed. Incorporated by Royal Charter. A Livery Company of the City of London. PUBLISHED BY: GOLF CLUB EVENTS The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, Please check on Company website for latest information Cobham House, 9 Warwick Court, Gray’s Inn, London WC1R 5DJ. EDITOR: Paul Smiddy BA (Eco n), FCA EMAIL: [email protected] FUNCTION PHOTOGRAPHY: Gerald Sharp Photography View images and order prints on-line. TELEPHONE: 020 8599 5070 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.sharpphoto.co.uk PRINTED BY: Printed Solutions Ltd 01494 478870 Except where specifically stated, none of the material in this issue is to be taken as expressing the opinion of the Court of the Company. -

Aerobatic Teams of the World

AIRFORCES MONTHLY 16-pAGE SUPPLEMENT JUNE 2013 Military DisplayEdited by Mark Broadbent Teamsof the World 2013 IR FORCES operate display teams Ato showcase the raw skills of airmanship, precision and teamwork that underpin military flying and to promote awareness and recruitment. They also have an ambassadorial role, promoting an air force and country overseas. Many covered in this supplement display overseas each year and, in some cases, frequently undertake international tours. Teams are also used to promote a country’s aerospace industry, playing informal roles in sales campaigns. As financial constraints continue to affect air force budgets globally, it will be interesting to see if aerobatic teams can maintain their military, political and industrial value. FRECCE TRICOLORI - AMI Military display teams of the world 2013 Australia Roulettes ARGENTINACruz del Sur Brazil Esquadrilha Brunei Alap-Alap ROYAL AUSTRALIAN AIR FORCE da Fumaça Formation Official designation: ROYAL BRUNEI AIR FORCE Royal Australian Air BRAZILIAN AIR FORCE (Angkatan Tentera Udara Force Aerobatic Team (Força Aérea Brasileira) DiRaja Brunei - ATUDB) Aircraft: 6 x Pilatus PC-9 English translation: English translation: Base: RAAF Base East Sale Smoke Squadron Eagle Formation History: The Roulettes team Official designation: Official designation: Royal was established in 1970 for the Brazilian Air Force Air Brunei Air Force Aerobatic Team RAAF’s Golden Jubilee using Demonstration Squadron Aircraft: 3 x Pilatus PC-7II the Vampire’s replacement, the Aircraft: 7 x Embraer Base: Rimba AB Macchi MB326. It grew from T-27 Super Tucano History: Alap-Alap Formation its initial four aircraft to seven Base: Pirassununga AB was established in February 2011 in 1981, but a year later was History: The team was to mark the 50th anniversary reduced to five. -

The Public Face of the Royal Canadian Air Force: the Importance of Air Shows and Demonstration Teams to the R.C.A.F

The Public Face of the Royal Canadian Air Force: The Importance of Air Shows and Demonstration Teams to the R.C.A.F. For History 394 A02 Dr. Timothy Balzer An Essay by Luke F. Kowalski V00738361 April 1st, 2013 1 For almost as long as Canada has had an air force, it has had demonstration flyers displaying the skill and daring required to be a pilot. From the first formation flight in 1919 on, demonstration teams have played an important role in keeping the Royal Canadian Air Force engaged and interacting with the Canadian public.1 Examining the history of R.C.A.F. air show participation and demonstration flying reveals that Canadian demonstration teams regularly faced adversity and criticisms, such as being too expensive or having ulterior motives, despite the fact that they have provided many important services and benefits to the R.C.A.F. This paper will argue that R.C.A.F. participation at air shows is not only an important way to demonstrate the skill and professionalism of the force, but also a significant part of public relations and a vital recruiting tool. For these reasons, today’s 431 Squadron Snowbirds are an integral part of the Canadian Forces. Rather than relying on secondary sources, this paper’s argument will primarily be supported by the information drawn from three oral history interviews conducted by the author of this paper. This is because reliable sources on the topic of Canadian air shows and demonstration flying is limited, and, as military historian Edward M. Coffman points out, if you want information “you must seek it among the impressions which can be obtained only from those who have lived a life amid particular surroundings.”2 The three interviewees are Major General Scott Eichel (Ret’d), former base commander and Chief Air Doctrine officer;3 Lieutenant 1 Dan Dempsey, A Tradition of Excellence: Canada's Air Show Team Heritage, (Victoria, B.C. -

Aerobatic Teams Free

FREE AEROBATIC TEAMS PDF Gerard Baloque | 128 pages | 19 Jan 2011 | HISTOIRE & COLLECTIONS | 9782352501688 | English | Paris, France Canadian Harvard Aerobatic Team He saw the need for a team Aerobatic Teams display using the Sukhoi aerobatic aircraft to add to his already popular solo displays. Warwick was obviously so impressed with the new format that he left the team to make yoghurt in Poland. They won 4 gold medals, 2 silver medals and 1 bronze medal. Inwe are concentrating on displaying in the UK. The team flew solely the Sukhoi aerobatic aircraft from to the end of Since the start ofthe Aerobatic Teams has just been flying the XA For more details: Link to XA41 Details. XtremeAir XA Paul hails from a flying family and got the aerobatic bug whilst Aerobatic Teams out after school Aerobatic Teams White Waltham airfield in Berkshire. His progression from private pilot to commercial pilot took him along the well trodden path of flying instructor, air-taxi pilot and airline pilot whilst simultaneously enjoying lots of aerobatics from White Waltham. The aerobatic career path took him into display aerobatics at the age of 22 and has been doing it ever since. Paul is the team leader of the Matadors and has been since The role of leader is to startle surprise and amaze the crowd whilst simultaneously not startling, surprising or amazing Steve Jones. Paul thinks he manages this most of the time! Paul Aerobatic Teams in Cambridgeshire with Aerobatic Teams wife and three children. Bornlearned to fly Steve Jones is the wingman in the team. -

CASM-Canadair-CL-13B-Sabre-F-86

CANADA AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUM AIRCRAFT CANADAIR CL-13B / F-86 SABRE MK 6 RCAF GOLDEN HAWKS SERIAL 23651 Introduction In August 1949, Canadair Limited, located at the Cartierville Airport facilities near Montreal, and the Department of National Defence (DND) signed a contract for the manufacture under license of 100 of the most advanced swept-wing day fighter aircraft of the time, the North American Aviation (NAA) F-86 Sabre. Assigned the Canadair model number CL-13, this order led to the largest aircraft production run in Canadair’s history. From 1949 to October 1958, Canadair Limited went on to produce some 1,815 examples of the famed fighter, in models ranging from the Sabre Mark (Mk) 1 up to the ultimate Sabre Mk 6 series, with a few special experimental models emanating from the production batches. The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) was the prime customer for the majority of these aircraft, but the power and reputation of the Canadian-built examples had other nations sit up and take notice, eventually culminating in numerous orders to North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and non-NATO countries. Canadair delivered versions of the CL-13 Sabre to the United States, Britain, Greece, Turkey, Italy, Yugoslavia, Germany, Columbia, and South Africa. RCAF variants served domestically training pilots and crews, and performed an important role in the Canadian commitment to provide a European air contingent for NATO operations. Some of the Canadian-based RCAF units wished to proudly show off their shiny new jet mounts to the general public, seeing as they were paying for them in one way or another, and permission was eventually granted for limited public expositions. -

The Canadian Forces Snowbirds Value in the Future: Public Affairs Role

THE CANADIAN FORCES SNOWBIRDS VALUE IN THE FUTURE: PUBLIC AFFAIRS ROLE Maj S.M. Scanlon-Simms JCSP 43 PCEMI 43 Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs do not represent Department of National Defence or et ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used Ministère de la Défense nationale ou des Forces without written permission. canadiennes. Ce papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2017. le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2017. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 43 – PCEMI 43 2016 – 2017 EXERCISE SOLO FLIGHT – EXERCICE SOLO FLIGHT THE CANADIAN FORCES SNOWBIRDS VALUE IN THE FUTURE: PUBLIC AFFAIRS ROLE Maj S.M. Scanlon-Simms “This paper was written by a student “La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College stagiaire du Collège des Forces in fulfilment of one of the requirements canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des of the Course of Studies. The paper is a exigences du cours. L'étude est un scholastic document, and thus contains document qui se rapporte au cours et facts and opinions, which the author contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et correct for the subject. It does not convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète pas necessarily reflect the policy or the nécessairement la politique ou l'opinion opinion of any agency, including the d'un organisme quelconque, y compris le Government of Canada and the gouvernement du Canada et le ministère Canadian Department of National de la Défense nationale du Canada. -

A History of the Peterborough Airport

DOUG ROBERTSON & TIGER MOTHS 55 YEARS APART PETERBOROUGH AIRPORT TODAY 1 2 PETERBOROUGH AVIATION HISTORY 1946 to 1980 3 DOUG ROBERTSON MAY 2008 4 By Doug Robertson After World War II in 1946, ex-RCAF pilots, Harvey Strub, Eldon Purves, Ed Brown, and several other RCAF types moved to Peterborough. They started building an airport called Skyboro and a flying service out of the field on the Chemong highway near the Lindsay turnoff. They operated two fleet Cunucks and a Globe Swift doing sightseeing trips and charter flights. The following year they ran into some bad luck and all work on the airport stopped. Several attempts were made to get it up and running again. The only flying that went on around Peterborough for many years was float equipped Cubs and Aeroncas. The only fuel that was available came by 45 gal. drum from Imperial Oil in Cobourg Ont. We all kept our own supplies. I contacted the Dept. of Transport in 1952 about getting the old Skyboro strip licensed. They visited Peterborough and gave me a list of work that had to be done to get the strip licensed. The east-west runway was only usable during dry weather conditions and several local people and a few tourists used the strip. Because of its poor condition, several aircraft were damaged over the years until the strip was improved. In 1953, along with a friend, Ken Colmer, we bought a DH Tiger Moth for $300. We painted and rejuvenated the Moth and eventually applied for a ferry permit to take it to the old Barker Airport on Dufferin Street in Toronto to Jim Leggett for its Certificate of Airworthiness. -

Dutch Air Force Open Days 2007

Aircraft Checklist Dutch Air Force Open House 2006 Open Dagen Koninklijke Luchtmacht 2006 Leeuwarden AB (LWR / EHLW) · Netherlands · 16 - 17 June 2006 www.militaryaircraft.de Serial Number Type Registration Unit Display A-109 H29 Belgian Air Component S AB.412SP R-01 303 Sq., Royal Netherlands AF F AB.412SP R-02 303 Sq., Royal Netherlands AF F AB-412SP R-03 303 Sq., Royal Netherlands AF F AH-64D Q-14 301 Sq., Royal Netherlands AF S AH-64D Q-26 301 Sq., Royal Netherlands AF S Alouette III A-247 300 Sq., Royal Netherlands AF F Alouette III A-275 300 Sq., Royal Netherlands AF F Alouette III A-301 300 Sq., Royal Netherlands AF F Alpha Jet 15202 Esq 103, "Asas de Portugal", Portugese AF F Alpha Jet 15206 Esq 103, "Asas de Portugal", Portugese AF F Alpha Jet 15208 Esq 103, "Asas de Portugal", Portugese AF F Alpha Jet 15250 Esq 103, "Asas de Portugal", Portugese AF F Alpha Jet E E117 / 7 "Patrouille de France", French AF F Alpha Jet E E130 / 1 "Patrouille de France", French AF F Alpha Jet E E134 / 6 "Patrouille de France", French AF F Alpha Jet E E163 / 2 "Patrouille de France", French AF F Alpha Jet E E31 / 8 "Patrouille de France", French AF F Alpha Jet E E41 / 4 "Patrouille de France", French AF F Alpha Jet E E46 / 0 "Patrouille de France", French AF F Alpha Jet E E73/312-RV "Patrouille de France", French AF F Alpha Jet E E75 / 3 "Patrouille de France", French AF F Alpha Jet E E94 / 5 "Patrouille de France", French AF F An-26 2408 24.zDL/241.dsl, Czech AF S AS.532U2 S-456 300 Sq., Royal Netherlands AF S AS.532UL S-400 300 Sq., Royal Netherlands -

Fern Villeneuve, Afc Lt-Col

LT-COL FERN VILLENEUVE, AFC hawkPART 1: THE FLEDGLING YEARS one One of Canada’s most illustrious airmen, Lt-Col FERN VILLENEUVE died on December 25, 2019. Best known as the founding leader of the RCAF’s Golden Hawks innovative formation aerobatic team, his 32-year Service career took in much else besides. In the first half of a previously unpublished 2005 interview with TAH’s Editor, Fern traces the first decade of his remarkable life in aviation T WAS WITH great sadness that we learned of the death of Lt-Col Fern Villeneuve AFC, one of Canada’s most distinguished aviators and a much-valued friend, on December 25, 2019. Back in 2005 I had the privilege — and Igreat pleasure — of interviewing Fern, best known in his home country as the founding leader of the Royal Canadian Air Force’s trailblazing Golden Hawks formation aerobatic display team. We met at Lee Bottom Flying Field in Indiana, USA, where he was a regular visitor to the annual Wood, Fabric & Tailwheels Fly-in. With his Globe Swift parked in the paddock outside, Fern, softly spoken and ever-willing to discuss anything and everything connected with aviation, devoted several hours to a wide- ranging conversation about his flying career. During our conversation he demonstrated his passion for flying of all kinds, from spine- cracking formation aerobatics in state-of-the-art jet fighters to the rather more sedate glider- TAH ARCHIVE TAH towing for students he later enjoyed. His ABOVE Fern Villeneuve during his leadership of the Royal Canadian Air Force’s Golden Hawks formation aero- batic display team, which he established in 1959. -

B&W+Foreign+Military+PDF.Pdf

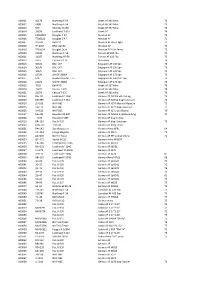

A00001 10476 Northrop F‐5A Greek AF 341 Mira 73 A00002 1400 Northrop F‐5A Greek AF 341 Mira 73 A00003 949 Sikorsky H‐19D Greek AF 357 Mira 70 A00004 29876 Lockheed T‐33A Greek AF 74 A00005 FAM6023 Douglas C‐47 Mexican AF 72 A00006 TTD6021 Douglas C‐47 Mexican AF 72 A00007 TPH‐02 Bell 212 Mexican AF Pres.Flight 72 A00008 TP‐0207 BN2 Islander Mexican AF 72 A00009 TP10014 Douglas DC‐6 Mexican AF 6 Gr Aereo 72 A00010 21193 Northrop F‐5A Turkish AF 192 Filo 73 A00011 21207 Northrop RF‐5A Turkish AF 192 Filo 73 A00012 1625 Cessna U‐17B Thai Army 74 A00013 300/A BAC‐167 Singapore AF 130 Sqn 73 A00014 301/B BAC‐167 Singapore AF 130 Sqn 73 A00015 302/C BAC‐167 Singapore AF 130 Sqn 73 A00016 127/H SIAI SF‐260M Singapore AF 172 Sqn 73 A00017 516 Hawker Hunter T.75 Singapore AF 140/141 Sqn 73 A00018 126/G SIAI SF‐260M Singapore AF 172 Sqn 73 A00019 7928 Bell 47G Greek AF 357 Mira 70 A00020 25971 Cessna T‐37C Greek AF 361 Mira 70 A00021 25973 Cessna T‐37C Greek AF 361 Mira 70 A00022 EB+121 Lockheed F‐104G German AF AKG52 wfu Erding 72 A00023 EB+399 Lockheed T‐33A German AF AKG52 displ Uetersen 71 A00024 JD+105 NA F‐86E German AF JG74 Munich Museum 72 A00025 JB+110 NA F‐86E German AF JG72 displ Uetersen 71 A00026 JA+332 NA F‐86E German AF JG71 wfu Buchel 72* A00027 EB+231 Republic RF‐84F German AF AKG52 displNeuaubing 72 A00028 ..+105 Republic F‐84F German AF displ Erding A00029 BR+239 Fiat G‐91R German AF displ Uetersen 71 A00030 KM+103 Transall German AF ferry serial A00031 PA+142 Sud Alouette II German Army HFB1 64 A00032 AA+014 Fouga Magister German