Up on the 606. Understanding the Use of a New Elevated Pedestrian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Economic Impact of Parks and Recreation Chicago, Illinois July 30 - 31, 2015

The Economic Impact of Parks and Recreation Chicago, Illinois July 30 - 31, 2015 www.nrpa.org/Innovation-Labs Welcome and Introductions Mike Kelly Superintendent and CEO Chicago Park District Kevin O’Hara NRPA Vice President of Urban and Government Affairs www.nrpa.org/Innovation-labs Economic Impact of Parks The Chicago Story Antonio Benecchi Principal, Civic Consulting Alliance Chad Coffman President, Global Economics Group www.nrpa.org/Innovation-labs Impact of the Chicago Park District on Chicago’s Economy NRPA Innovation Lab 30 July 2015 The charge: is there a way to measure the impact of the Park Districts assets? . One of the largest municipal park managers in the country . Financed through taxes and proceeds from licenses, rents etc. Controls over 600 assets, including Parks, beaches, harbors . 11 museums are located on CPD properties . The largest events in the City are hosted by CPD parks 5 Approach summary Relative improvement on Revenues generated by value of properties in parks' events and special assets proximity . Hotel stays, event attendance, . Best indicator of value museum visits, etc. by regarding benefits tourists capture additional associated with Parks' benefit . Proxy for other qualitative . Direct spending by locals factors such as quality of life indicates economic . Higher value of properties in significance driven by the parks' proximity can be parks considered net present . Revenues generated are value of benefit estimated on a yearly basis Property values: tangible benefit for Chicago residents Hypothesis: . Positive benefit of parks should be reflected by value of properties in their proximity . It incorporates other non- tangible aspects like quality of life, etc. -

Wasson Way Trail Design a Place-Based Approach to Building World-Class Infrastructure

WASSON WAY TRAIL DESIGN A PLACE-BASED APPROACH TO BUILDING WORLD-CLASS INFRASTRUCTURE PREPARED FOR THE CITY OF CINCINNATI & THE WASSON WAY ORGANIZATION Darren Meyer • Overall Project Lead & Point of Responsibility Building Community Through • Lead Designer: Character, Experience & Function Vibrant Public Space • Public Engagement & Public Process Lead Clete Benken • MKSK Team Leader • Project Manager & Client Point of Contact • Team Supervisor & Project Quality Control Joe Nickol • MKSK Urban Design • Urban Development Strategies International Forerunner in Michael King • Public Engagement & Public Processes People-First Transportation Planning • Transportation Design Steven Smith • Burgess & Niple Project Manager • Civil & Transportation Engineering Unparalleled Experience in • Technical & Regulatory Engineering Lead Engineering Complex Infrastructure Steven Anslinger • Transportation Lead • Bridge Engineering INTRODUCTIONS SAFETY EFFICIENCY MOBILITY SINGLE USE A TO B COMMUNITY EVENTS DINING & SOCIAL LIFE 18 HR VIBRANCY & AMBIENCE NEIGHBORHOOD SHOPPING ART & PLACEMAKING MADISONVILLE MADISON ROAD D A MIAMI ROAD O 71 R ERIE AVENUE Y A K W AN ARK MONTGOMERY ROAD B P COLUMBIA PLAINVILLE ROAD RY RED TO TOWNSHIP VIC OAKLEY SQUARE NORWOOD XAVIER UNIVERSITY INDIAN HILL MURRAY PATH OAKLEY COLUMBIA TOWNSHIP ROOKWOOD COMMONS & HYDE PARK GOLF AND COUNTRY CLUB EVANSTON DANA AVE PAVILION BUSINESS HYDE PARK DISTRICT PLAZA MARIEMONT WASSON ROAD MARBURG AVENUE SQUARE WITHROW HIGH SCHOOL DOGWOOD EVANSTON EAST HYDE FAIRFAX PARK WALNUT HILLS MARIEMONT PARK -

CHICAGO PARK DISTRICT $8,000,000* Generalobligation B

PRELIMINARY OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED OCTOBER 20, 2016 NEW ISSUES – FULL BOOK-ENTRY S&P: AA+/stable outlook Fitch: AA-/stable outlook Kroll: AA/stable outlook (See “RATINGS” herein) In the opinion of Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP and Tristan & Cervantes, Co-Bond Counsel, under existing law, if there is continuing compliance with applicable requirements of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, interest on the Bonds will not be includable in gross income for federal income tax purposes. Interest on the Bonds is not required to be included as an item of tax preference for purposes of computing individual or corporate “alternative minimum taxable income.” However, interest on the Bonds is includable in corporate earnings and profits and therefore must be taken into account when computing corporate alternative minimum taxable income for purposes of the corporate alternative minimum tax. Interest on the Bonds is not exempt from Illinois income taxes. See “TAX MATTERS” herein. $119,000,000* CHICAGO PARK DISTRICT $75,000,000* General Obligation Limited Tax Park Bonds, Series 2016A $8,000,000* General Obligation Limited Tax Refunding Bonds, Series 2016B $17,000,000* General Obligation Limited Tax Refunding Bonds, Series 2016C $4,000,000* General Obligation Unlimited Tax Refunding Bonds, Series 2016D (Personal Property Replacement Tax Alternate Revenue Source) $15,000,000* General Obligation Unlimited Tax Refunding Bonds, Series 2016E (Special Recreation Activity Alternate Revenue Source) Dated: Date of Issuance Due: January 1 and November 15, as shown -

The Backbone of the Lakefront Trail

A new elevated pathway provides safe passage for pedestrians and cyclists near one of the Windy City’s premier tourist destinations. The BACKBONE of the Lakefront BY Trail JOHANN F. AAKRE, S.E., P.E., AND JANET ATTARIAN Photos: © 2015 Trey Cambern, courtesy HNTB CHICAGO’S LAKEFRONT TRAIL is a popular cycling, Lake Shore Drive bridge. Construction of the supporting steel walking and running venue for residents and tourists alike. superstructure for phase 1 is now finished as the $27.9 million The 1,750-ft-long, $60 million “Navy Pier Flyover” now first segment nears completion. under construction as part of Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s “Build- ing a New Chicago” program will eventually relieve congestion Eliminating a Bottleneck along the most heavily used section of the 18.5-mile trail. With 60,000 users traversing this segment of the Lakefront Site constraints and limited clearances created by a park- Trail during peak use, in the late 1990s the Chicago Department ing garage, a residential high-rise, local streets, highway access of Transportation (CDOT) began looking at ways to alleviate ramps and several parks, a serpentine alignment was essentially the bottleneck created when trail users crossed paths with pedes- the only option for the grade-separated pathway. Aesthetics trians on city streets, local vehicle traffic and highway entrance were equally as important as functionality because the flyover ramps. All of this congestion, combined with missing or deterio- will be visible from every angle in a highly visible part of the rated pavement markings, lack of way-finding signage and poor city. -

Pdfs/2000874-Equitable-Development- Environmentalists and EJ Advocates (See Sandler & Pezzullo, 2007)

Cities xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Cities journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cities “We're not in the business of housing:” Environmental gentrification and the nonprofitization of green infrastructure projects ⁎ Alessandro Rigolona, , Jeremy Némethb a Department of Recreation, Sport and Tourism, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA b Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Colorado Denver, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Environmental gentrification, or the influx of wealthy residents to historically disenfranchised neighborhoods Environmental gentrification due to new green spaces, is an increasingly common phenomenon around the globe. In particular, investments in Environmental justice large green infrastructure projects (LGIPs) such as New York's High Line have contributed to displacing long- Urban green space term low-income residents. Many consider environmental gentrification to be an important environmental Park nonprofits justice issue, but most of this research has focused on distributional justice; that is, quantifying whether LGIPs Sustainability have indeed contributed to gentrifying neighborhoods around them. Limited work has focused on procedural justice in the context of environmental gentrification, or how planning processes can shape project outcomes. This is a particularly critical oversight because many LGIP planning processes are led by nonprofits, a govern- ance model that has already raised important equity concerns in the context of planning and maintenance of smaller neighborhood parks. Yet less is known about the impacts of park nonprofits leading LGIPs. To address these gaps, we study the planning process of the 606, a rails-to-trails project located in Chicago, U.S. that contributed to environmental gentrification. -

Friends of the Lakefront Trail: Public Engagement Report

Friends of the Lakefront Trail: Public Engagement Report May, 2013 THE CASE FOR CHICAGO’S LAKEFRONT TRAIL... Chicago’s Lakefront Trail is the busiest trail in the United States, with peak daily usage reaching 30,000 people at key points. The 18-mile trail is maintained by the Chicago Park District. It’s a popular destination for residents and tourists alike, attracting people from across the region for recreation, transportation and athletic training. In order to understand how the trail can better meet the needs of Chicagoans, Friends of the Lakefront Trail facilitated a community outreach process in 2012 to learn what trail users think about their trail experience. This report summarizes the findings and sets forth principles for improving the Lakefront Trail experience. DevelopeD by the FrienDs oF the lakeFront trail 3 PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT REPORT FRIENDS OF THE LAKEFRONT TRAIL PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS About Friends of the Lakefront Trail 6 Lakefront Trail Principals 7 Survey Methodology 9 Profile of Respondents 10 Survey Results 11 Survey Maps 12 Tables??? 28 5 PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT REPORT ABOUT FRIENDS OF THE Lakefront Trail Friends of the Lakefront Trail is an initiative of the Active Transportation Alliance in partnership with Friends of the Parks and the Chicago Area Runners Association, representing the interests of Lakefront Trail users and advocating to improve conditions for recreation and transportation on the trail. active transportation alliance The Active Transportation Alliance (Active Trans) is a non-profit, member-based advocacy organization that works to make bicycling, walking and public transit so safe, convenient and fun that we will achieve a significant shift from environmentally harmful, sedentary travel to clean, active travel. -

Table Version Website 031621.Xlsx

CHICAGO PARK DISTRICT PARK CAPITAL PROJECTS 2011-2021* As of March 1, 2021 PARK YEAR PARK NAME NO PROG** SUB PROGRAM PROJECT DESCRIPTION STATUS COMPLETE $ ABBOTT (ROBERT) 259 FR Swimming Pool Pool Retrofit - compliance COMPLETE 2012 ABBOTT (ROBERT) 259 SI Playground Chicago Plays! - new equipment COMPLETE 2013 ABBOTT (ROBERT) 259 FR Minor Rehab Misc. pool stairs COMPLETE 2015 ABBOTT (ROBERT) 259 FR Swimming Pool Pool - rehab COMPLETE 2016 ABBOTT (ROBERT) 259 SI Paving 2016 DW Paving COMPLETE 2017 ABBOTT (ROBERT) 259 SI Landscape Tree planting COMPLETE 2018 ABBOTT (ROBERT) 259 SI Site Improvement Park improvements COMPLETE 2018 ABBOTT (ROBERT) 259 FR Concrete Masonry Structural Field house - masonry PRE-DESIGN ADA (SAWYER GARRETT) 45 FR Swimming Pool Pool Retrofit - compliance COMPLETE 2012 ADA (SAWYER GARRETT) 45 FR Minor Rehab Entrance and washrooms COMPLETE 2012 ADA (SAWYER GARRETT) 45 FR HVAC and Energy Efficiency HVAC energy management COMPLETE 2012 ADA (SAWYER GARRETT) 45 SI Paving Paving - playground COMPLETE 2012 ADA (SAWYER GARRETT) 45 SI Lighting Lighting - parking lot COMPLETE 2012 ADA (SAWYER GARRETT) 45 SI Playground Chicago Plays! - new playground equipment COMPLETE 2013 ADA (SAWYER GARRETT) 45 SI Courts Slam Dunk Basketball Court - rehab with lighting COMPLETE 2013 ADA (SAWYER GARRETT) 45 FR Swimming Pool Misc. rehab COMPLETE 2015 ADA (SAWYER GARRETT) 45 FR Concrete Masonry Structural Field house - masonry and tuckpointing COMPLETE 2017 ADA (SAWYER GARRETT) 45 SI Athletic Field Athletic field - rehab COMPLETE 2018 * ADA (SAWYER -

Cities Alive: Towards a Walking World Foreword Gregory Hodkinson | Chairman, Arup Group

Towards a walking world Towards a walking world 50 DRIVERS OF CHANGE 50 BENEFITS 40 ACTIONS 80 CASE STUDIES This report is the product of collaboration between Arup’s Foresight + Research + Innovation, Transport Consulting and Urban Design teams as well as other specialist planners, designers and engineers from across our global offices. We are also grateful for the expert contributions from a range of external commentators. Contacts Susan Claris Chris Luebkeman Associate Director Arup Fellow and Director Transport Consulting Global Foresight + Research + Innovation [email protected] [email protected] Demetrio Scopelliti Josef Hargrave Architect Associate Masterplanning and Urban Design Foresight + Research + Innovation [email protected] [email protected] Local Contact Stefano Recalcati Associate Masterplanning and Urban Design [email protected] Released June 2016 #walkingworld 13 Fitzroy Street London W1T 4BQ arup.com driversofchange.com © Arup 2016 Contents Foreword 7 Executive summary 9 Introduction 14 Benefits 28 Envisioning walkable cities 98 Achieving walkable cities 110 Next steps 153 References 154 Acknowledgements 165 5 higher experience parking walk neighbourhoods community route increasing culture places strategies improving travel change research policies air needs road work study temporary services route digital cycling efcient physical local time potential order accessible transport improve attractive context investment city risk towards space walkable use people world live urban data -

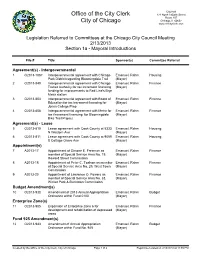

Referred Matters Report

City Hall Office of the City Clerk 121 North LaSalle Street Room 107 City of Chicago Chicago, IL 60602 www.chicityclerk.com Legislation Referred to Committees at the Chicago City Council Meeting 2/13/2013 Section 1a - Mayoral Introductions File # Title Sponsor(s) Committee Referral Agreement(s) - Intergovernmental 1 O2013-1087 Intergovernmental agreement with Chicago Emanuel, Rahm Housing Park District regarding Bloomingdale Trail (Mayor) 2 O2013-848 Intergovernmental agreement with Chicago Emanuel, Rahm Finance Transit Authority for tax increment financing (Mayor) funding for improvements to Red Line's Bryn Mawr station 3 O2013-853 Intergovernmental agreement with Board of Emanuel, Rahm Finance Education for tax increment financing for (Mayor) Jones College Prep 4 O2013-858 Intergovernmental agreement with Metra for Emanuel, Rahm Finance tax iIncrement financing for Bloomingdale (Mayor) Bike Trail Project Agreement(s) - Lease 5 O2013-810 Lease agreement with Cook County at 5333 Emanuel, Rahm Housing N Western Ave (Mayor) 6 O2013-811 Lease agreement with Cook County at 9059 Emanuel, Rahm Housing S Cottage Grove Ave (Mayor) Appointment(s) 7 A2013-17 Appointment of Simone E. Freeman as Emanuel, Rahm Finance member of Special Service Area No. 19, (Mayor) Howard Street Commission 8 A2013-18 Appointment of Peter C. Toalson as member Emanuel, Rahm Finance of Special Service Area No. 29, West Town (Mayor) Commission 9 A2013-20 Appointment of Lawrence O. Powers as Emanuel, Rahm Finance member of Special Service Area No. 33, (Mayor) Wicker Park & Bucktown Commission Budget Amendment(s) 10 O2013-938 Amendment of 2013 Annual Appropriation Emanuel, Rahm Budget Ordinance within Fund 0100 (Mayor) Enterprise Zone(s) 11 O2013-905 Expansion of Enterprise Zone 6 for Emanuel, Rahm Finance development and rehabilitation of depressed (Mayor) areas Fund 925 Amendment(s) 12 O2013-943 Amendment of Annual Appropriation Emanuel, Rahm Budget Ordinance within Fund No. -

Comparing Three Elevated Parks—The High Line, 606, and High Bridge

sustainability Article What Park Visitors Survey Tells Us: Comparing Three Elevated Parks—The High Line, 606, and High Bridge Jisoo Sim 1,* , Cermetrius Lynell Bohannon 1 and Patrick Miller 1 Department of Landscape Architecture, College of Architecture and Urban Studies, Virginia Tech., Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA; [email protected] (C.L.B.); [email protected] (P.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-540-449-5143 Received: 3 November 2019; Accepted: 10 December 2019; Published: 22 December 2019 Abstract: Many cities have replaced abandoned transportation infrastructure with an elevated park to gain increased economic benefits by developing old fabric. By following this trend, most studies to this point have only focused on the economic rewards from the replacement rather than its uses in the real world. This study aims to understand how park visitors use elevated parks through a park visitors’ survey. The authors selected three representative elevated parks—the High Line in New York City, the 606 in Chicago, and the High Bridge in Farmville—for the study and asked visitors about their activities, perceived benefits, and satisfaction. Results indicate that the 606, a mixed-use elevated park, allows visitors to engage in high-intensity activity, the High Line as an elevated urban park provides visitors public arts and gardens, and the High Bridge as an elevated green park provided visitors with a connection to unique natural scenery. This study, as the first to compare three different elevated parks, contributes to an understanding of who uses elevated parks and how they use elevated parks. Keywords: elevated park; park visitor survey; High Line; 606; Bloomingdale Trail; High Bridge 1. -

Your Next Big Idea Is Here

Your next big idea is here. harris.uchicago.edu Welcome to the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy. What sets the University of Chicago apart? We lead with a focus on inquiry and a commitment to impact. We empower individuals to challenge conventional thinking in pursuit of original ideas. UChicago research has led to revolutionary theories of economics and tools to effect social change. In all we do, we are driven to dig deeper, push further, and ask bigger questions—and to leverage our knowledge to enrich all human life. 92 140+ 100+ Nobel Laureates affiliated Interdisciplinary Research Programs, initiatives, with the University, including Centers and Institutes and partnerships in six Nobel Prize winners currently over 48 nations and on faculty at UChicago on every continent 1 1 The University of Chicago CHICAGO HIGHLIGHTS American Writers Museum The 606 / Bloomingdale Trail Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art Chicago is: The Windy City. Bahá’í Temple The City of Big Shoulders. The Plant vertical farm The City that Works. Design Museum of Chicago National Museum of Mexican Art Chicago is known by many names Garfield Park Conservatory but its spirit is singular. One of River cruise architecture tours The Second City comedy club the great American cities and the largest city in the Midwest, TO-DO LIST Chicago offers all the perks of an Cubs or White Sox game international metropolis. Lakefront beach barbecue Free music and movies in Millennium Park And the University of Chicago campus, with its dramatic mixture of Gothic and Postmodern Live jazz at the Green Mill architecture, its world-famous Frank Lloyd Wright Free contemporary art exhibitions home, quirky student-run cafés, and more Nobel at Hyde Park Art Center Prize winners than just about anywhere else in Talks and exhibitions at the DuSable the world, is the setting for your next big idea. -

A Look Back on Eight Years of Progress

MOVING CHICAGO FORWARD: A LOOK BACK ON EIGHT YEARS OF PROGRESS MAYOR RAHM EMANUEL MOVING CHICAGO FORWARD • A LOOK BACK ON EIGHT YEARS OF PROGRESS LETTER FROM THE MAYOR May 2, 2019 Dear Fellow Chicagoans, It has been the honor of my lifetime to serve the people of this great city as mayor for eight years. Together, we have addressed longstanding challenges, overcome old obstacles and confronted new headwinds. At the outset of my administration, Chicago was beset by fiscal, economic and academic crises. Many thought our best days were behind us, and that the ingenuity and ability to rise to meet great challenges that had defined our city for generations was part of our past, but not our future. In response, Chicagoans came together and showed the resolve and resilience that define the character of this great city. Today, Chicago’s fiscal health is stronger than it has been in many years, with a smaller structural deficit, a larger rainy day fund, true and honest accounting of city finances, and dedicated recurring revenues for all four city pension funds. Our economic landscape is dramatically improved, with historic lows in unemployment, the highest level of jobs per-capita in the city in over five decades, and a record amount of corporate relocations and foreign direct investment. Academically, Chicago’s students are raising the bar for success and making our city proud. Every year for the past seven, a new record number of Chicago’s students have graduated high school. More graduates than ever now go to college. Stanford University found CPS students are learning faster than 96 percent of students of all districts in the United States.