Male Vulnerability Seed, Semen and Phallus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jyotirlinga Temple Tour

12- Jyotirlinga Temple Tour Day 1 – Arrive Kolkatta Arrive at Kolkata Airport and transfer to the hotel for overnight stay. Day 2 – Kolkatta / Kiul – Overnight train Morning sightseeing tour of Kolkata city. Rest of the afternoon at leisure. Evening transfer to Howrah Railway Station to board overnight train for Kiul. Day 3 – Kiul – Visit Baijnath Temple Arrive early in the morning at Kiul Railway Station. arrival and continue driving to Deogarh to visit Baijnath temple. Later after visit continue driving to Bodhgaya for overnight stay. Basic accommodation is available. Day 4 – Bodhgaya / Varanasi Morning visit Buddhist sites at Bodhgaya. Afternoon drive to Varanasi and check in at the hotel. Overnight stay. Day 5 – Varanasi Early morning proceed to River Ganges for holy dip and have boat ride. Temple of Lord Viswanath is situated in Varanasi. Known formerly as Kashi or Benares, this ancient city set on the banks of the river Ganga, is one of the holiest cities in India. Being one of the oldest living and most holy city’s in India, Varanasi attracts a lot of tourists. Day 6 – Varanasi / Haridwar – Overnight train Transfer to Railway Station in time to board overnight train for Haridwar. Overnight on board. Day 7 – Arrive Haridwar / Rishikesh Arrive Haridwar in morning. Arrival and proceed for the temple tour of Haridwar and then drive for Rishikesh. Overnight stay. Day 8 – Rishikesh / Hanuman Chati Morning drive to Hanuman Chatti. Check in at Guest House / lodge on arrival. Overnight at the Lodge. Day 9 – Hanuman Chatti / Yamunotri / Hanujman Chatti Proceed for same day excursion to Yamunotri- temple dedicated to Goddess Yamuna . -

Somnath Travel Guide - Page 1

Somnath Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/somnath page 1 devotion at the Somnath Temple. It finds Max: Min: Rain: 31.79999923 19.79999923 2.20000004768371 mention in the Hindu puranas and the 7060547°C 7060547°C 6mm Somnath Mahabharata. Literally translated as the Apr Home to one of the 12 sacred Shiva "Lord of the Moon," the town and its temple Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. celebrate the most auspicious Karthik Jyotirlinga's in India, the grandeur Max: Min: Rain: 0.0mm Poornima (or full-moon) in the month of 32.09999847 22.79999923 of Somnath is sure to take your 4121094°C 7060547°C November/ December with full fervour and May breath away. The lofty shikharas flavour. The reverberating sounds of Shiv Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. add colour to the town and flavour bhajans and the legend, culture and Max: Min: Rain: to the lives of people who visit it. tradition surrounding it, will accompany you 32.79999923 26.20000076 4.40000009536743 during your entire stay at Somanth. It has 706055°C 2939453°C 2mm been popularly dubbed as the "shrine Jun eternal," for its ability to stand tall in the Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, umbrella. face of destruction - it's been rebuilt six Famous For : City Max: 32.5°C Min: Rain: times. 27.39999961 134.800003051757 8530273°C 8mm Somnath is famous for its grand Shiva When To Jul temple, one of the 12 revered Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, Jyotirlingas, located right on the shore of the umbrella. Arabian Sea, in Max: Min: Rain: VISIT 30.70000076 26.60000038 269.799987792968 Junagadh District. -

Temple Foods of India’’

Report on stall of “Temple foods of India’’ National “Eat Right Mela” from 14th to 16th December, 2018 at IGNCA near India Gate, New Delhi The first National “Eat Right Mela” is being organized from 14th to 16th December, 2018 at IGNCA near India Gate, New Delhi. This Mela is being held along with the established and well-known ‘Street Food Festival’ organized by NASVI since the past 10 years. One of the attractions was the stall on “Temple Foods of India” under the pavilion “Flavours of India” which showcased cuisines of India’s most famous temples and the variety of different prasad offered to pilgrims. Following are 13 famous Temples from across India participated in the festival: S. No. Name of temple 1 Arulmigu Meenakshi Sundareshwarar Temple, Madura i, Tamil Nadu 2 Dhandayuthapani Swamy Temple,Palani,Tamil Nadu 3 Ramanathaswamy Temple, Rameshwaram, Tamil Nadu 4 Arunachaleshwarar Temple, Thiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu 5 ISKCON Temple, Delhi 6 Chittaranjan Park Kali Mandir, Delhi 7 Gurudwara, Delhi 8 Somnath Temple, Gujarat 9 Shree Kashtubhanjan Hanumanji Temple, Gujarat 10 Ambaji Temple, Gujarat 11 Swaminarayan temple BAPS, Maharashtra 12 Shirdi Sai Baba Temple, Maharashtra 13 Shrinathji Mandir Nathdwara, Rajasthan Some of the temples are associated with FSSAI under BHOG (Blissful Hygienic Offering to God) which focuses on the hygienic preparation of prasad and training & capacity building of the Temple food ecosystem to ensure the same. Day 1 at Eat Right Mela 14 dec to 16 dec, 2018 Four Temples from Tamil Nadu had brought different kind of Prasad. And these temples have already implemented FSMS in their temples. -

Enchanting Gujarat

Enchanting Gujarat 06 Nights / 07 Days 2N Dwarka – 2N Somnath (via. Porbandar) - 2N Diu PACKAGE HIGHLIGHTS: In Dwarka, visit Nageshwar Jyotirlinga, Rukmini Temple and Dwarkadhish Temple Enroute visit of Porbandar – Visit Kirti Temple In Somnath, visit Triveni Sangam, Bhalka Tirth and Geeta Mandir Chowpatty In Diu, visit St. Paul Church & Diu Museum. Sightseeing tours by private air- conditioned vehicle Start and End in Rajkot ITINERARY: Day 01 Arrival in Rajkot – Dwarka (230 kms / 4.5 hours) Meet our representative upon arrival Rajkot and proceed to Dwarka. On arrival check into your hotel and enjoy rest of the day at leisure. Overnight in Dwarka. Day 02 Sightseeing in Dwarka After breakfast, take a dip in the sacred River Gomti River according to the customs of the place. Visit the Nageshwar Jyotirlinga, which is one of the 12 Jyotirlingas that are mentioned in the Shiva Purana. Also visit Gopi Talav pond nearby and get to learn about the stories of Lord Krishna and the Gopis. Continue further to visit the island of Bet Dwarka. On your way back, visit the Rukmini Temple and other famous temples in the coastal area. Witness the famous evening aarti at the Dwarkadhish Temple, before returning to the hotel. At the end of a well- spent spiritual day, return to your hotel for overnight stay in Dwarka. Day 03 - Dwarka to Somnath via Porbandar (230 kms / 4.5 hours) After breakfast, check out from the hotel and proceed from Dwarka to Porbandar early in the morning. Visit the Kirti Temple, the memorial built in honour of Mahatma Gandhi. -

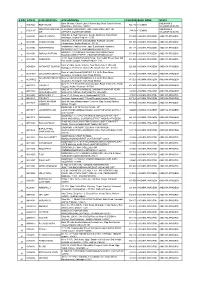

S No Atm Id Atm Location Atm Address Pincode Bank

S NO ATM ID ATM LOCATION ATM ADDRESS PINCODE BANK ZONE STATE Bank Of India, Church Lane, Phoenix Bay, Near Carmel School, ANDAMAN & ACE9022 PORT BLAIR 744 101 CHENNAI 1 Ward No.6, Port Blair - 744101 NICOBAR ISLANDS DOLYGUNJ,PORTBL ATR ROAD, PHARGOAN, DOLYGUNJ POST,OPP TO ANDAMAN & CCE8137 744103 CHENNAI 2 AIR AIRPORT, SOUTH ANDAMAN NICOBAR ISLANDS Shop No :2, Near Sai Xerox, Beside Medinova, Rajiv Road, AAX8001 ANANTHAPURA 515 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 3 Anathapur, Andhra Pradesh - 5155 Shop No 2, Ammanna Setty Building, Kothavur Junction, ACV8001 CHODAVARAM 531 036 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 4 Chodavaram, Andhra Pradesh - 53136 kiranashop 5 road junction ,opp. Sudarshana mandiram, ACV8002 NARSIPATNAM 531 116 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 5 Narsipatnam 531116 visakhapatnam (dist)-531116 DO.NO 11-183,GOPALA PATNAM, MAIN ROAD NEAR ACV8003 GOPALA PATNAM 530 047 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 6 NOOKALAMMA TEMPLE, VISAKHAPATNAM-530047 4-493, Near Bharat Petroliam Pump, Koti Reddy Street, Near Old ACY8001 CUDDAPPA 516 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 7 Bus stand Cudappa, Andhra Pradesh- 5161 Bank of India, Guntur Branch, Door No.5-25-521, Main Rd, AGN9001 KOTHAPET GUNTUR 522 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta, P.B.No.66, Guntur (P), Dist.Guntur, AP - 522001. 8 Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW8001 GAJUWAKA BRANCH 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 9 Gajuwaka, Anakapalle Main Road-530026 GAJUWAKA BRANCH Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW9002 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH -

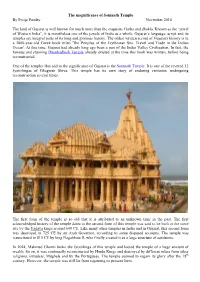

The Magnificence of Somnath Temple by Pooja Pandey November 2016

The magnificence of Somnath Temple By Pooja Pandey November 2016 The land of Gujarat is well known for much more than the exquisite Garba and dhokla. Known as the “jewel of Western India”, it is nonetheless one of the jewels of India as a whole. Gujarat’s language, script and its temples are integral parts of its long and glorious history. The oldest written record of Gujarat's history is in a 2000-year-old Greek book titled 'The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean'. At this time, Gujarat had already long ago been a part of the Indus Valley Civilization. In fact, the famous and stunning Dwarkadhish Temple already existed at the time this book was written, before being reconstructed. One of the temples that add to the significance of Gujarat is the Somnath Temple. It is one of the revered 12 Jyotirlingas of Bhagwan Shiva. This temple has its own story of enduring centuries, undergoing reconstruction several times. The first form of the temple is so old that it is attributed to an unknown time in the past. The first acknowledged history of the temple dates to the second form of this temple was said to be built at the same site by the Yadava kings around 649 CE. Like many other temples in India and in Gujarat, this second form was destroyed in 725 CE by an Arab Governor, according to some disputed accounts. The temple was resuscitated in 815 CE by king Nagabhata II, who finally created it as a large structure of sandstone. -

Incredible Gujarat 06 Nights / 07 Days

Incredible Gujarat 06 Nights / 07 Days Tour Highlights: Highlights: Dwarka: 02 Nights Bet Dwarka Nageshvara Jyotirlinga Gopi Talab Rukmani Temple Gomati Ghats Sudama Setu Somnath: 01 Night Somnath Temple Kirti Mandir (on the way Porbandar) Diu: 01 Night Diu Fort Sent Paul Church Gangeshwar Temple Diu Beaches Rajkot: 01 Night Watson Museum Kaba Gandhi no delo Ramakrishna Ashram Vadodara: 01 Night Lakshmi Vilas Palace Maharaja Fateh Singh Museum Sur Sagar Lake Meal: 06 Breakfast & 06 Dinner Day Wise Itinerary: Day : 1 Ahmedabad – Jamnagar – Dwarka (Driving: Ahmedabad – Dwarka // Approx. 08 hrs // 453 kms). 1 / 5 Arrive at Ahmedabad, pick-up from Airport/Railway station or Hotel. Proceed to Dwarka En-route visit Lakhota Lake, Lakhota Museum and Bala Hanuman Temple known for its nonstop Ramdhun since 1956 and it mentioned in Guinness Book of World Records. later proceed to Dwarka. Dwarka is an ancient city in the north western Indian state of Gujarat. It’s known as a Hindu pilgrimage site. The ancient Dwarkadhish Temple has an elaborately tiered main shrine, a carved entrance and a black-marble idol of Lord Krishna. Dwarka Beach and nearby Dwarka Lighthouse offer views of the Arabian Sea. Southeast, Gaga Wildlife Sanctuary protects migratory birds and endangered species like the Indian wolf. Arrival Dwarka and check in Hotel. Evening free for leisure activities. In evening, enjoy Dinner at Hotel, Overnight stay at Dwarka. Meal: Breakfast & Dinner Day : 2 Dwarka - Bet Dwarka - Dwarka Early Morning enjoy Mangla Aarti Darshan. Later enjoy Breakfast at hotel. Later visit Bet Dwarka, believed to be the original abode of Lord Krishna. -

PILGRIM CENTRES of INDIA (This Is the Edited Reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the Same Theme Published in February 1974)

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA A DISTINCTIVE CULTURAL MAGAZINE OF INDIA (A Half-Yearly Publication) Vol.38 No.2, 76th Issue Founder-Editor : MANANEEYA EKNATHJI RANADE Editor : P.PARAMESWARAN PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA (This is the edited reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the same theme published in February 1974) EDITORIAL OFFICE : Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan Trust, 5, Singarachari Street, Triplicane, Chennai - 600 005. The Vivekananda Kendra Patrika is a half- Phone : (044) 28440042 E-mail : [email protected] yearly cultural magazine of Vivekananda Web : www.vkendra.org Kendra Prakashan Trust. It is an official organ SUBSCRIPTION RATES : of Vivekananda Kendra, an all-India service mission with “service to humanity” as its sole Single Copy : Rs.125/- motto. This publication is based on the same Annual : Rs.250/- non-profit spirit, and proceeds from its sales For 3 Years : Rs.600/- are wholly used towards the Kendra’s Life (10 Years) : Rs.2000/- charitable objectives. (Plus Rs.50/- for Outstation Cheques) FOREIGN SUBSCRIPTION: Annual : $60 US DOLLAR Life (10 Years) : $600 US DOLLAR VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements 1 2. Editorial 3 3. The Temple on the Rock at the Land’s End 6 4. Shore Temple at the Land’s Tip 8 5. Suchindram 11 6. Rameswaram 13 7. The Hill of the Holy Beacon 16 8. Chidambaram Compiled by B.Radhakrishna Rao 19 9. Brihadishwara Temple at Tanjore B.Radhakrishna Rao 21 10. The Sri Aurobindo Ashram at Pondicherry Prof. Manoj Das 24 11. Kaveri 30 12. Madurai-The Temple that Houses the Mother 32 13. -

Jyotirlinga Darshan Yatra 2020

Om Namah Shivaya Jyotirlinga Darshan Yatra 2020 सौराष्ट्रे सोमनाथं च श्रीशैले मल्ललका셍जुनम्। उज्जल्िनिां महाकालमो敍कारममलेश्वरम्॥ परलिां वैद्यनाथं च डाककनिां भीमश敍करम्। सेतजबनधे तज रामेशं नागेशं दा셁कावने॥ वाराणसिां तज ल्वश्वेशं त्र्ि륍बकं गौतमीतटे। ल्हमालिे तज केदारं घज�मेशं च ल्शवालिे॥ एताल्न 煍िोल्त셍लु敍गाल्न सािं प्रातः पठेन्नरः। सप्त셍नमकृतं पापं समरणेन ल्वन�िल्त॥ Yatra Overview: Jyotirlinga is considered as one of the prime worship spots for the devotees of Lord Shiva. In Hindu Mythology, it is believed that Jyotirlinga means "The Radiant symbol of the Almighty", so it is the resplendent flame of the almighty solidified to make the worship of it simple. There are a total of 64 Jyotirlingas that are well spread around the landscape of India. However, 12 Jyotirlingas are presumed to be very auspicious and highly revered among them. These jyotirlingas are positioned in eight states of India, likes of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamilnadu, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. As per the Hindu mythologies, visiting Jyotirlingas is an important pilgrimage that wades off all the sins and makes the soul sacrosanct and pure. The devotees visiting these Jyotirlingas become chaste, pure and calm. After visiting these Jyotirlingas, devotees turn home with illuminated and enlightened with highest and divine knowledge. It is also believed that wishes are fulfilled after visiting and having Darshan of these sacred Jyotirlingas. Thus, these Jyotirlingas are visited by Lord Shiva's devotees every year in huge numbers. -

Puri in Orissa, During 12Th to 15Th Century on the Basis of Epigraphical Records

Pratnatattva Vol. 23; June 2017 Journal of the Department of Archaeology Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ISSN 1560-7593 Pratnatattva Vol. 23; June 2017 Editorial Board Sufi Mostafizur Rahman Executive Editor Ashit Boran Paul Jayanta Singh Roy Mokammal Hossain Bhuiyan Bulbul Ahmed Shikder Mohammad Zulkarnine Pratnatattva is published annually in June. It publishes original research articles, review articles, book reviews, short notes, seminar and conference news. The main objective of this journal is to promote researches in the field of Archaeology, Art History, Museology and related relevant topics which may contribute to the understanding and interpretation of the dynamic and varied interconnections among past, people and present. This journal is absolutely academic and bilingual. One can write and express his/her views either in Bangla (with a summary in English) or in English (with a summary in Bangla). Contribution to this Journal should be sent to Executive Editor, Pratnatattva, Journal of the Department of Archaeology, Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka ([email protected]). Contributors should strictly follow the guidelines printed in the Journal or can ask for the copy of guideline from the Executive Editor. The Journal is distributed from the Department of Archaeology, Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka – 1342. Cover Concept : Jayanta Singh Roy Front Cover : Hindu, Buddhist & Jaina deities Publisher : Department of Archaeology, Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Phone Numbers: 880-2-7791045-51, ext. 1326 Email: [email protected] Printers : Panir Printers, Dhaka Price : 500 BDT/ 10 USD © : Department of Archaeology, Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh. EDITORIAL In this volume (Vol. 23) of Pratnatattva contains articles across diverse topics. -

Iconic Sites

30 ICONIC SITES Making Swachhata Icons Under inspiration from the Kanvashram • Kanvashram, located 14 KM from Kotdwar in Uttarakhand, has Hon’ble Prime Minister, 100 immense historical and archeological significance. • Surrounded by serene beauty of forest, Kanvashram has its iconic places in India are to be existence from 5500 years. Legend has it that sages like Vishvamitra and Kanva have meditated on this holy land for developed in phases as models of years. • It is also said that King Bharat was born here in Kanvashram. The cleanliness (Swachhata). name of our country- ‘Bharatvarsha’ has been derived from his name. The project is being coordinated by Ministry of Drinking Water & Sanitation, in collaboration with Union Ministries of Housing and Urban Affairs, Tourism, Culture, state governments, municipal and Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation local agencies with support from leading Public Sector (Swachh Bharat Mission) Website: www.mdws.gov.in, Telephone No. : 011-24368614 Undertakings. 30 iconic sites have been taken up in phase-I , II & III. Phase-I: Iconic Sites Phase-I: Iconic Sites Meenakshi Temple, Madurai, Tamil Nadu • Madurai temple city was built in the 6th century A.D., during the Pandiyan rule, and is one of the oldest cities in the world. • It evolved, over the centuries, as the epicenter of Dravidian as well as Tamil culture. • Considered as the state cultural capital, the Meenakshi Amman temple alone attracts 15,000 visitors every day during the weekdays and around 25,000 on weekends. • Plastic ban, renovation of toilets, mechanical sand sweeping trucks to reduce pollution around temple, battery operated vehicles for solid waste collection, compactor bins, water ATMs, appointment of 25 Swachh Police to ensure cleanliness in and around the temple are some of the initiatives taken. -

Amazing Gujarat

Amazing Gujarat [rev_slider amazing-gujarat] OUR PROGRAM FIRST DAY- Arrive Ahmedabad – Lothal – Rajkot (215 Kms / 4 Hrs) Arrive at Ahmedabad Airport/Railway Station and proceed towards Rajkot. En-route visit Lothal which literally means “mound of the dead”. Lothal is the most extensively excavated site of Harappan site in India and therefore allows the most insight into the story of the Indus Valley civilization, its exuberant flight, and its tragic decay. Arrive Rajkot and check in at hotel. If time permits visit Swamy Narayan temple built out of hand carved stones and the temple is renowned world over for its social work and humanitarian services. Night stay in Rajkot. SECOND DAY - Rajkot – Dwarka (230 Kms/ 4 Hrs) After breakfast proceed towards Dwarka - town of Lord Krishna. Arrive Dwarka and check in at hotel. Later visit Dwarkadish Temple. Take a holy dip in Gomti River, later leave to visit Nageshwar Jyotirling, Gopi Talav, Bet Dwarka, and on way back do visit Rukmani Temple. Evening visit other temples on coastal area, attend evening aarti at Dwarkadish temple. Overnight stay in Dwarka. THIRD DAY - Dwarka – Porbandar – Somnath (240 Kms/ 4 Hrs) After breakfast proceed towards Somnath. Enroute visit Porbandar – the birth place of Mahatma Gandhi and Sudama. Visit Kirti Mandir and Sudama Temple. Later drive to Somnath. Arrive Somnath and check in at hotel. Later visit Somnath Temple, a renowned Shiva Temple and considered one of the 12 Jyotirlinga Temples and one of the most visited Shiva Temples in India. Attend evening aarti and see the sound and light show at Somnath Temple premises.