Lightspeed Magazine Issue 36, May 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jean Harlow ~ 20 Films

Jean Harlow ~ 20 Films Harlean Harlow Carpenter - later Jean Harlow - was born in Kansas City, Missouri on 3 March 1911. After being signed by director Howard Hughes, Harlow's first major appearance was in Hell's Angels (1930), followed by a series of critically unsuccessful films, before signing with Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer in 1932. Harlow became a leading lady for MGM, starring in a string of hit films including Red Dust (1932), Dinner At Eight (1933), Reckless (1935) and Suzy (1936). Among her frequent co-stars were William Powell, Spencer Tracy and, in six films, Clark Gable. Harlow's popularity rivalled and soon surpassed that of her MGM colleagues Joan Crawford and Norma Shearer. By the late 1930s she had become one of the biggest movie stars in the world, often nicknamed "The Blonde Bombshell" and "The Platinum Blonde" and popular for her "Laughing Vamp" movie persona. She died of uraemic poisoning on 7 June 1937, at the age of 26, during the filming of Saratoga. The film was completed using doubles and released a little over a month after Harlow's death. In her brief life she married and lost three husbands (two divorces, one suicide) and chalked up 22 feature film credits (plus another 21 short / bit-part non-credits, including Chaplin's City Lights). The American Film Institute (damning with faint praise?) ranked her the 22nd greatest female star in Hollywood history. LIBERTY, BACON GRABBERS and NEW YORK NIGHTS (all 1929) (1) Liberty (2) Bacon Grabbers (3) New York Nights (Harlow left-screen) A lucky few aspiring actresses seem to take the giant step from obscurity to the big time in a single bound - Lauren Bacall may be the best example of that - but for many more the road to recognition and riches is long and grinding. -

P-234 W.E. Jones Theatre Collection, 1916-1933

P-234 W.E. Jones Theatre Collection, 1916-1933 Repository: Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Span Dates: 1916 – 1933 Extent: 1 letter box; 1 oversize box, 1 folder Language: English Abstract: W.E. Jones was a theatre manager in San Diego and Los Angeles who was associated with several theatres between 1916 and 1933 particularly the Pickwick and Superba in San Diego, and the Superba and Largo in Los Angeles. The W.E. Jones Theatre Collection is comprised of individual photographs as well as a scrapbook of clippings and photographs which focus on stage sets and lobby displays for various films—mainly Universal films of 1920. There are a few photos of other theatres such as the Cameo and the Rampart for which an association with W.E. Jones could not be determined. Conditions Governing Use: Permission to publish, quote or reproduce must be secured from the repository and the copyright holder Conditions Governing Access: Research is by appointment only Preferred Citation: W.E. Jones Theatre Collection, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History Related Holdings: P-26 Motion Picture Collection GC 1146 Theater Programs Collection, ca. 1893-1958 GC 1155ov Theater in Los Angeles Scrapbook, 1886-1924 Seaver Center for Western History Research P-234 Historical Note: Little information could be found regarding any of the theatres pictured in the collection except that they existed between 1916 and 1933. The Superba Theatre in Los Angeles was located at 518 S. Broadway, which later became the site of the Roxie Theatre in 1932. -

Strangest of All

Strangest of All 1 Strangest of All TRANGEST OF LL AnthologyS of astrobiological science A fiction ed. Julie Nov!"o ! Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute Features G. %avid Nordley& Geoffrey Landis& Gregory 'enford& Tobias S. 'uc"ell& (eter Watts and %. A. *iaolin S#ires. + Strangest of All , Strangest of All Edited originally for the #ur#oses of 'EACON +.+.& a/conference of the Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute 0EA$1. -o#yright 0-- 'Y-N--N% 4..1 +.+. Julie No !"o ! 2ou are free to share this 5or" as a 5hole as long as you gi e the ap#ro#riate credit to its creators. 6o5ever& you are #rohibited fro7 using it for co77ercial #ur#oses or sharing any 7odified or deri ed ersions of it. 8ore about this #articular license at creati eco77ons.org9licenses9by3nc3nd94.0/legalcode. While this 5or" as a 5hole is under the -reati eCo77ons Attribution3 NonCo77ercial3No%eri ati es 4.0 $nternational license, note that all authors retain usual co#yright for the indi idual wor"s. :$ntroduction; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :)ar& $ce& Egg& =ni erse; < +..+ by G. %a id Nordley :$nto The 'lue Abyss; < 1>>> by Geoffrey A. Landis :'ac"scatter; < +.1, by Gregory 'enford :A Jar of Good5ill; < +.1. by Tobias S. 'uc"ell :The $sland; < +..> by (eter )atts :SET$ for (rofit; < +..? by Gregory 'enford :'ut& Still& $ S7ile; < +.1> by %. A. Xiaolin S#ires :After5ord; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :8artian Fe er; < +.1> by Julie No !"o ! 4 Strangest of All :@this strangest of all things that ever ca7e to earth fro7 outer space 7ust ha e fallen 5hile $ 5as sitting there, isible to 7e had $ only loo"ed u# as it #assed.; A H. -

July 2020 C the Orion Publishing Group

The Orion Publishing Group New Titles January – July 2020 Weidenfeld & cNicolson | White Rabbit | Trapeze | Gollancz | Orion Spring | OrionC Fiction | Seven Dials ORIONBOOKS.CO.UK Cover artwork from Red At The Bone by Jacqueline Woodson, published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson (p7) Contents I Weidenfeld & Nicolson | P4 Fiction and Non-Fiction White Rabbit | P26 Fiction and Non-Fiction Trapeze | P32 Fiction and Non-Fiction Gollancz | P48 Sci-Fi and Fantasy Orion Fiction | P60 Fiction Orion Spring | P86 Non-Fiction Seven Dials | P92 Non-Fiction Contacts | P98 ORIONBOOKS.CO.UK Artwork from This Happy by Niamh Campbell, published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson (p19) 4 Fiction & Non-Fiction f WEIDENFELD & NICOLSON is one of the most prestigious and dynamic literary imprints in British and international publishing, home of groundbreaking, award-winning, thought-provoking books since 1949. Our passion for extraordinary writing dates back to our two founders, who were responsible for introducing some of the twentieth century’s most remarkable voices – Vladimir Nabokov, Isaiah Berlin, Sybille Bedford, Eric Hobsbawm, Edna O’Brien, Jorge Luis Borges and many others – to a wide readership. They launched their publishing house with the idea of building bridges and opening minds through exceptional works of literature: we have been carrying on their legacy ever since. We publish history, memoir, ideas, popular science, biography, narrative non-fiction, crime and thrillers, translated fiction and literary fiction of all kinds. 5 Who were the great diplomats of history – and what can their achievements tell us about the most important issues of our time? History does not run in straight lines. It is made by men and women and by accident. -

An Evening to Honor Gene Wolfe

AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE Program 4:00 p.m. Open tour of the Sanfilippo Collection 5:30 p.m. Fuller Award Ceremony Welcome and introduction: Gary K. Wolfe, Master of Ceremonies Presentation of the Fuller Award to Gene Wolfe: Neil Gaiman Acceptance speech: Gene Wolfe Audio play of Gene Wolfe’s “The Toy Theater,” adapted by Lawrence Santoro, accompanied by R. Jelani Eddington, performed by Terra Mysterium Organ performance: R. Jelani Eddington Closing comments: Gary K. Wolfe Shuttle to the Carousel Pavilion for guests with dinner tickets 8:00 p.m Dinner Opening comments: Peter Sagal, Toastmaster Speeches and toasts by special guests, family, and friends Following the dinner program, guests are invited to explore the collection in the Carousel Pavilion and enjoy the dessert table, coffee station and specialty cordials. 1 AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE By Valya Dudycz Lupescu A Gene Wolfe story seduces and challenges its readers. It lures them into landscapes authentic in detail and populated with all manner of rich characters, only to shatter the readers’ expectations and leave them questioning their perceptions. A Gene Wolfe story embeds stories within stories, dreams within memories, and truths within lies. It coaxes its readers into a safe place with familiar faces, then leads them to the edge of an abyss and disappears with the whisper of a promise. Often classified as Science Fiction or Fantasy, a Gene Wolfe story is as likely to dip into science as it is to make a literary allusion or religious metaphor. A Gene Wolfe story is fantastic in all senses of the word. -

James GUNN Not Enough

Spring 2013 LonestarCon 3 Progress rePort 4 The fourth Progress Report for LoneStarCon 3, the 71st Worldcon, to be held August 29–September 2, 2013, in San Antonio, Texas Welcome to the New Frontier A bid for the 73rd World Science Fiction Convention Spokane, Washington August 19-23, 2015 Let's bring the Worldcon to the Northwest! We want to share with the rest of the world · a huge active local and regional communities of fans, authors, artists, filkers, costumers, gamers, otaku, and more creative folks · in the heart of a beautiful, thriving city with hundreds of restaurants nearby, and cultural and outdoor activities (with perfect weather in August) · at a 21st century facility with a Broadway-quality theater for events. Find out more at spokanein2015.org. The Spokane in 2015 Worldcon Bid is a project of SWOC. Letter From the Chair Howdy y’all! Welcome to Progress Report 4. My name is Randall Shepherd, and I am the new significance of being tasked with Chair for LoneStarCon 3. selecting not only the 2015 Worldcon I’m writing this the day after the final ballot for the Hugo Awards was announced. host city, but also the site of the 2014 The process was rather like watching a duck gliding smoothly over the surface of a NASFiC. If you find you can’t attend lake… then you realize there’s a lot of furious paddling going on underneath! in person, this is a good way to still participate and show your support for There were so many folks who helped to make this Hugo ballot announcement Worldcon. -

Starshipsofa Stories: Volume 1

VOLUME 1 Contents Tony C. Smith . Ed’s Letter 3 Michael Moorcock . London Bone 5 Ken Scholes . .Into The Blank Where Life Is Hurled 19 Elizabeth Bear . Tideline 29 Michael Bishop Vinegar Peace (or, The Wrong-Way Used-Adult Orphanage) 37 Spider Robinson . In The Olden Days 51 Gord Sellar . Lester Young And The Jupiter’s Moons’ Blues 55 Lawrence Santoro . Little Girl Down The Way 77 Gene Wolfe . .The Vampire Kiss 87 Benjamin Rosenbaum . The Ant King: A California Fairy Tale 91 Joe R. Lansdale . Godzilla’s Twelve Step Program 103 Alastair Reynolds . The Sledge-maker’s Daughter 109 Ken Macleod . Jesus Christ, Reanimator 123 Peter Watts . The Second Coming Of Jasmine Fitzgerald 131 Ruth Nestvold . Mars: A Travelers’ Guide 145 Jeffrey Ford . Empire Of Ice Cream 151 ILLUSTRATIONS Skeet Scienski . Cover Art Adam Koford . When they Come 4 Anton Emdin . .Weather Forecasting 36 Jouni Koponen . Little Girl Down The Way 77 Bob Byrne . .The Vampire Kiss 87 Steve Boehme . The Ant King: A California Fairy Tale 91 Jouni Koponen . Empire Of Ice Cream 151 EDiteD BY TonY C. SMitH Copyright © 2009 by StarShipSofa. Cover design, interior layout & design by Dee Cunniffe. www.StarShipSofa.com PErMissiONS: “London Bone” © Michael Moorcock, 1998. New Worlds, 1998, David Garnett, White Wolf. Reprinted by permission of the author. “Into The Blank Where Life Is Hurled” © Ken Scholes, 2005. Writers of the Future Volume XXI, Aug 2005, Algis Budrys, Galaxy Press. Reprinted by permission of the author. “Tideline” © Elizabeth Bear, 2007. Asimov’s Science Fiction, June 2007 Jun 2007, Sheila Williams, Dell Magazines.Reprinted by permission of the author. -

Lane Is Chairman of Township Board Mrs. Prentis Dies in Philadelphia

ONE DOLLAR THE YEAR V /lf £i VOLUME NINETLEN. NO, 1 OCEAN GROVE. NEW JERSEY, SATURDAY, JANUARY 7, 1 9 1 1 &LANE IS CHAIRMAN AUTO CLUB INDEPENDENT JANUARY GRAND JURY MRS. PRENTIS DIES WiiSLEY LAKE BIDS OPENED ENGINEER HOWLAND A SUICIDE Slate Body llas^Wlllidrawn From Ihe Neptune’s Representative is Randolph IN PHILADELPHIAImprovement Conlracl is Awarded Depression Leads Railroad Man lo OF TOWNSHIP BOARD American Association Miller Gen. Paiterson, ol Ocean Grove. Take His Life - " ’/•A t / $ $ f i | By supporting the constitution and 6n‘ Tuesday at .Freehold, Sheriff - .BidS ' for the boulevard • improve ■;Early-, last Friday- ' morning " VVII-^ by-laws of the New Jersey ‘Automo Hetrick selected the grand jury for SDE HAS LONG IDtNTIFIED WITH ment of the head of Wesley lake fiiim .flenry Howlandfpr ihahy years/ 1HURLEV SUCCEEDS BULIT AS TREflS- bile and Motor Chib the members at the January term of court. After be were opened by Secretary . Cole/ of aii engineer .on th^/C eiitra!.’Railrp.a'd.:’.'^i® ^ . ' ’ :tlieir large meethig< held recently, ing sworn in,, the members ;of. the LOCAL HOTEL INTERESTS the-Ocean Groye: Association;, on of New .Jersey and wiio. retired from ' . JJRER OF THAT BODY s ;voted to sustain the board of trus^ jury listened to a- charge delivered Tl i u r fc d a y a f tor no o n,, Four bids were active; sefvlee July . 5 last, committed tees'who recently, decided that af by Justice Willard P.-Voorliees. In presented j as follows:' - \ , ... - siiIcidoVat Uio Long Branch horao o£; filiation with tlio American Automo- this-, charge, .mentlbn was made > 61 Geli.V John i-C. -

WARNER ARCHIVE DVD COLLECTION – Informal Collection List As of Winter 2013

WARNER ARCHIVE DVD COLLECTION – informal collection list as of Winter 2013. For updated information or to arrange viewing, please e-mail [email protected]. Item # Title DVD8925 2 WEEKS IN ANOTHER TOWN [1962] DVD7519 20,000 YEARS IN SING SING [1933] DVD9691 24 HOURS TO KILL [1965] DVD7301 3 SAILORS AND A GIRL [1953] DVD8754 -30- [1959] DVD10749 5 TIME CHAMPION [2012] DVD9877 7 FACES OF DR. LAO [1963] DVD9174 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET CAPTAIN KIDD [1952] DVD7192 ABDICATION, THE [1974] DVD7206 ABE LINCOLN IN ILLINOIS [1940] DVD7171 ABOVE AND BEYOND [1952] DVD7934 ABOVE SUSPICION [1943] DVD9781 ACROSS THE WIDE MISSOURI [1951] DVD7520 ACROSS TO SINGAPORE [1928] DVD7201 ACTRESS, THE [1953] DVD10743 ADA [1961] DVD8764 ADAM’S WOMAN [1969] DVD9634 ADVANCE TO THE REAR [1963] DVD9780 ADVENTURE [1945] DVD7191 ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN, THE [1939] DVD7216 ADVENTURES OF MARK TWAIN, THE [1944] DVD7743 ADVENTURES OF ONE ESKIMO, THE [2009] DVD9976 AFFAIRS OF DOBIE GILLIS, THE [1953] DVD8554 AGATHA [1978] DVD10336 AGE OF CONSENT, THE [1932] DVD9136 AGE OF INNOCENCE, THE [1934] DVD7195 AH, WILDERNESS! [1935] DVD7669 AIRBORNE [1993] DVD9800 AKIRA KUROSAWA’S DREAMS [1990] DVD7226 AL CAPONE [1959] DVD9807 ALEX IN WONDERLAND [1970] DVD8845 ALIAS THE DOCTOR [1932] DVD8118 ALIBI IKE [1935] DVD10532 ALICE [THE COMPLETE FIRST SEASON] [DISC 1 OF 3] DVD10533 ALICE [THE COMPLETE FIRST SEASON] [DISC 2 OF 3] DVD10534 ALICE [THE COMPLETE FIRST SEASON] [DISC 3 OF 3] DVD10772 ALICE [THE COMPLETE SECOND SEASON] [DISC 1 OF 3] DVD10773 ALICE [THE COMPLETE SECOND SEASON] -

2017 Hugo Report #2 the Nominations Tally

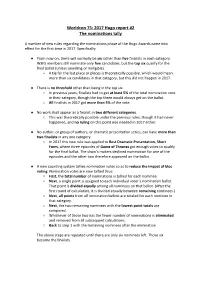

Worldcon 75: 2017 Hugo report #2 The nominations tally A number of new rules regarding the nominations phase of the Hugo Awards came into effect for the first time in 2017. Specifically: ● From now on, there will normally be six rather than five finalists in each category. WSFS members still nominate only five candidates, but the top six qualify for the final ballot (unless unwilling or ineligible). ○ A tie for the last place or places is theoretically possible, which would mean more than six candidates in that category, but this did not happen in 2017. ● There is no threshold other than being in the top six. ○ In previous years, finalists had to get at least 5% of the total nomination vote in their category, though the top three would always get on the ballot. ○ All finalists in 2017 got more than 5% of the vote. ● No work shall appear as a finalist in two different categories. ○ This was theoretically possible under the previous rules, though it had never happened, and no ruling on this point was needed in 2017 either. ● No author, or group of authors, or dramatic presentation series, can have more than two finalists in any one category. ○ In 2017 this new rule was applied to Best Dramatic Presentation, Short Form, where three episodes of Game of Thrones got enough votes to qualify for the final ballot. The show’s makers declined nomination for one of the episodes and the other two therefore appeared on the ballot. ● A new counting system tallies nomination votes so as to reduce the impact of bloc voting. -

BSFG News 469 October 2010

NOVACON 40 – the Brum Group’s own convention and the longest-running regional convention in the UK, will be once again held at The Park Inn, 296 Mansfield Brum Group News Road, Nottingham, NG5 2BT. Dates are November 12th to The Free Monthly Newsletter of the 14th November. Guests of Honour are Iain M Banks and our Co-President Brian Aldiss, O.B.E. Full details at BIRMINGHAM SCIENCE FICTION GROUP http://novacon.org.uk/ October 2010 Issue 469 Honorary Presidents: BRIAN W ALDISS, O.B.E. & HARRY HARRISON FUTURE MEETINGS OF THE BSFG November 5th – SF author CHARLES STROSS Committee: December 3rd – Christmas Social Vernon Brown (Chairman); Pat Brown (Treasurer); Jan 2011 – Annual General Meeting and Auction Vicky Stock (Secretary); Rog Peyton (Newsletter Editor); Dave Corby (publicity Officer); William McCabe (Website); Feb – QUIZ with University SF Society NOVACON 40 Chairman: Vernon Brown Mar – tba website: Email: April 8th – comic SF/Fantasy author ROBERT RANKIN www.birminghamsfgroup.org.uk/ [email protected] BRUM GROUP NEWS #469 (October 2010) copyright 2010 for Birmingham Friday 18th October SF Group. Designed by Rog Peyton (19 Eves Croft, Bartley Green, Birmingham, B32 3QL – phone 0121 477 6901 or email rog.peyton [at] btinternet [dot] com). Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the committee or ADAM the general membership or, for that matter, the person giving the ‘opinion’. Thanks to all the named contributors in this issue and to William McCabe who sends me reams of news items every month which I sift through for the best/most entertaining items. ROBERTS Adam Roberts was ‘born two-thirds of the way through the last century’ and educated ‘at a rundown state school in Kent’ and the ancient University of Aberdeen where he graduated with a degree in English and Classics. -

SF/SF #103 When I Noticed (And I Really Should Have Noticed This Way Earlier) Minor Errors in the Spelling of Goh’S

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 104 Editor-in-Chief: Jean Martin April 28, 2010 Editor: España Sheriff email: [email protected] Proofreader: Rina Weisman Compositor: Tom Becker Contents Editorial............................................................................................ España Sheriff.................................... ...................................................................... 2 World Horror Con in Brief............................................................. Christopher J. Garcia........ ........................................................................................ 3 Hugo Nomination Thoughts............................................................ Christopher J. Garcia........ ........................................................................................ 4 Nova Albion...................................................................................... España Sheriff.................. Photos by Deborah Kopec and Jean Martin................... 6 WonderCon Gets Better Every Year.............................................. España Sheriff.................. Photo by Nicole Klepper.............................................. 10 Encom Press Conference and Flynn Lives Rally.......................... JohnnyAbsinthe................ Photos by JohnnyAbsinthe and Jet Set Sean................ 14 Letters of Comment......................................................................... Jean Martin....................... .....................................................................................