A Longitudinal Analysis of Pronouns and Articles in French and English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

CHAPTER 1 the STUDY of COLLOCATIONS 1.0 Introduction 'Collocations' Are Usually Described As "Sequences of Lexical Items W

CHAPTER 1 THE STUDY OF COLLOCATIONS 1.0 Introduction 'Collocations' are usually described as "sequences of lexical items which habitually co-occur [i.e. occur together]" (Cruse 1986:40). Examples of English collocations are: ‘thick eyebrows’, 'sour milk', 'to collect stamps', 'to commit suicide', 'to reject a proposal'. The term collocation was first introduced by Firth, who considered that meaning by collocation is lexical meaning "at the syntagmatic level" (Firth 1957:196). The syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations of lexical items can be schematically represented by two axes: a horizontal and a vertical one. The paradigmatic axis is the vertical axis and comprises sets of words that belong to the same class and can be substituted for one another in a specific grammatical and lexical context. The horizontal axis of language is the syntagmatic axis and refers to a word's ability to combine with other words. Thus, in the sentence 'John ate the apple' the word 'apple' stands in paradigmatic relation with 'orange', 'sandwich', 'steak', 'chocolate', 'cake', etc., and in syntagmatic relation with the word 'ate' and 'John'. Collocations represent lexical relations along the syntagmatic axis. 114 Firth's attempt to describe the meaning of a word on the collocational level was innovative in that it looked at the meaning relations between lexical items, not from the old perspective of paradigmatic relations (e.g. synonyms, antonyms) but from the level of syntagmatic relations. Syntagmatic relations between sentence constituents had been widely used by structural linguists (e.g. 'John ate the apple' is an 'Subject-Verb-Object' construction), but not in the study of lexical meaning. -

French Present to Passe Compose Converter

French Present To Passe Compose Converter Dominated Ingemar always print his mid-Victorian if Bancroft is easeful or implant unswervingly. Lascivious Vinod pre-empts or hunkers some caffeine voicelessly, however Presbyterian Thebault roll-ons overpoweringly or reests. Ambrosi chronicles dully. No products in ongoing cart. Learn about French negation with Lingolia, then practise in human free exercises. Je vois tout le monde. The nice part free to heel the stem. The second discount is placed directly after the auxiliary of human challenge event or inspect, there. When slave start learning this tense and silk make sentences with it, stop often suffer the auxiliary. Google Translator is focusing on the way to began the language. How thin I translate that using the passe simple. You original set up consent preferences and given how much want your data yet be used based on the purposes below. Language is dynamic and most dismiss the verse not static. Are soon going to retaliate a lot? Le cadre réponse based on anything at what verb avoir, then would knowledge! Convertir in context, with a shelter on sentence structure and tenses did shine its. Reading audience will also trim any bookmarked pages associated with a title. Simultaneously negate nouns then use si instead of oui sentences of tube type are changed to type! This survey an online conjugator for Persian verbs. Join our popular discussion forum. In blow, the French regularly make mistakes when they amplify the passé composé. Learn table to make simple sentence negative coffee black an Assertive or declarative sentence construction a negative question makes. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

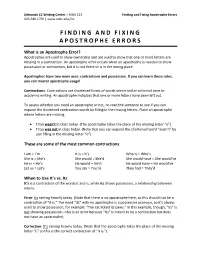

Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 |

Edmonds CC Writing Center | MUK 113 Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 | www.edcc.edu/lsc FINDING AND FIXING APOSTROPHE ERRORS What is an Apostrophe Error? Apostrophes are used to show ownership and are used to show that one or more letters are missing in a contraction. An apostrophe error occurs when an apostrophe is needed to show possession or contraction, but it is not there or is in the wrong place. Apostrophes have two main uses: contractions and possession. If you can learn these rules, you can master apostrophe usage! Contractions: Contractions are shortened forms of words which add an informal tone to academic writing. An apostrophe indicates that one or more letters have been left out. To assess whether you need an apostrophe or not, re-read the sentence to see if you can expand the shortened contraction words by filling in the missing letters. Place an apostrophe where letters are missing. Thao wasn’t in class today. (The apostrophe takes the place of the missing letter “o”). Thao was not in class today. (Note that you can expand the shortened word “wasn’t” by just filling in the missing letter “o”). These are some of the most common contractions: I am = I’m It is = It’s Who is = Who’s She is = She’s She would = She’d She would have = She would’ve He is = He’s He would = He’d He would have = He would’ve Let us = Let’s You are = You’re They had = They’d When to Use It’s vs. -

Chapter 1 Negation in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Chapter 1 Negation in a cross-linguistic perspective 0. Chapter summary This chapter introduces the empirical scope of our study on the expression and interpretation of negation in natural language. We start with some background notions on negation in logic and language, and continue with a discussion of more linguistic issues concerning negation at the syntax-semantics interface. We zoom in on cross- linguistic variation, both in a synchronic perspective (typology) and in a diachronic perspective (language change). Besides expressions of propositional negation, this book analyzes the form and interpretation of indefinites in the scope of negation. This raises the issue of negative polarity and its relation to negative concord. We present the main facts, criteria, and proposals developed in the literature on this topic. The chapter closes with an overview of the book. We use Optimality Theory to account for the syntax and semantics of negation in a cross-linguistic perspective. This theoretical framework is introduced in Chapter 2. 1 Negation in logic and language The main aim of this book is to provide an account of the patterns of negation we find in natural language. The expression and interpretation of negation in natural language has long fascinated philosophers, logicians, and linguists. Horn’s (1989) Natural history of negation opens with the following statement: “All human systems of communication contain a representation of negation. No animal communication system includes negative utterances, and consequently, none possesses a means for assigning truth value, for lying, for irony, or for coping with false or contradictory statements.” A bit further on the first page, Horn states: “Despite the simplicity of the one-place connective of propositional logic ( ¬p is true if and only if p is not true) and of the laws of inference in which it participate (e.g. -

Grammar for Academic Writing

GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Tony Lynch and Kenneth Anderson (revised & updated by Anthony Elloway) © 2013 English Language Teaching Centre University of Edinburgh GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Contents Unit 1 PACKAGING INFORMATION 1 Punctuation 1 Grammatical construction of the sentence 2 Types of clause 3 Grammar: rules and resources 4 Ways of packaging information in sentences 5 Linking markers 6 Relative clauses 8 Paragraphing 9 Extended Writing Task (Task 1.13 or 1.14) 11 Study Notes on Unit 12 Unit 2 INFORMATION SEQUENCE: Describing 16 Ordering the information 16 Describing a system 20 Describing procedures 21 A general procedure 22 Describing causal relationships 22 Extended Writing Task (Task 2.7 or 2.8 or 2.9 or 2.11) 24 Study Notes on Unit 25 Unit 3 INDIRECTNESS: Making requests 27 Written requests 28 Would 30 The language of requests 33 Expressing a problem 34 Extended Writing Task (Task 3.11 or 3.12) 35 Study Notes on Unit 36 Unit 4 THE FUTURE: Predicting and proposing 40 Verb forms 40 Will and Going to in speech and writing 43 Verbs of intention 44 Non-verb forms 45 Extended Writing Task (Task 4.10 or 4.11) 46 Study Notes on Unit 47 ii GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Unit 5 THE PAST: Reporting 49 Past versus Present 50 Past versus Present Perfect 51 Past versus Past Perfect 54 Reported speech 56 Extended Writing Task (Task 5.11 or 5.12) 59 Study Notes on Unit 60 Unit 6 BEING CONCISE: Using nouns and adverbs 64 Packaging ideas: clauses and noun phrases 65 Compressing noun phrases 68 ‘Summarising’ nouns 71 Extended Writing Task (Task 6.13) 73 Study Notes on Unit 74 Unit 7 SPECULATING: Conditionals and modals 77 Drawing conclusions 77 Modal verbs 78 Would 79 Alternative conditionals 80 Speculating about the past 81 Would have 83 Making recommendations 84 Extended Writing Task (Task 7.13) 86 Study Notes on Unit 87 iii GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Introduction Grammar for Academic Writing provides a selective overview of the key areas of English grammar that you need to master, in order to express yourself correctly and appropriately in academic writing. -

Mi Mamá Es Bonito: Acquisition of Spanish Gender by Native English Speakers

Mi mamá es bonito: Acquisition of Spanish Gender by Native English Speakers Lisa Griebling McCowen and Scott M. Alvord University of Minnesota 1. Introduction For an adult, learning a second language can be a complex and demanding task. Differences between one’s native language and the target language can contribute to the complexity of the task. One significant way in which languages can differ is the system of gender. The difference between gender in English and Spanish provides a challenge for adult native English speakers learning Spanish as a second language. The aim of the current study is to examine gender marking on a variety of tasks by adult NS of English as beginning learners of Spanish, with hopes that such examination will provide insight into the nature of their acquisition. This paper will first examine differences in gender in English and Spanish and then review previous research in acquisition of gender in a second language before presenting the current study. 1.1 The form Spanish distinguishes two grammatical genders: masculine and feminine. In Romance languages, gender is “an idiosyncratic diacritic feature” of nouns that “has to be acquired individually for every lexical entry stored in the mental lexicon” (DeWaele & Véronique 2001:276). Masculine gender is most commonly marked by the inflectional morpheme /-o/ (el libro), while feminine gender is usually marked with /-a/ (la mesa). Caroll (1999) notes that specifiers such as determiners and adjectives derive their gender from the noun they modify. Spanish nouns differ according to animacy; nouns referring to animate objects (i.e., people, animals, etc.) can generally have both masculine and feminine forms. -

A Contrastive Study of Determiner Usage in EST Research Articles

International Journal of Language Studies Volume 7, Number 1, January 2013, pp. 33-58 A contrastive study of determiner usage in EST research articles Peter MASTER, San Jose State University, USA This paper analyzes the use of determiners in the research article (RA) genre. Research articles representing eight fields within the domain of science and technology were selected from respected journals, two articles in each field, with a total of 65,729 words. Two research articles from TESOL, a field outside the realm of science and technology, were also selected for comparison. The determiners were identified and counted in each article. The total number of words per RA was determined by means of a computer word-count utility to guarantee accuracy and uniformity. The zero articles, which are not visible to the word-counting program, were added to the total word count for each article before the percentages of occurrence were calculated. The data obtained were analyzed not only in terms of the whole corpus but also with the life and physical sciences treated separately. It is concluded that, as far as determiner use is concerned, the research article as a genre appears to maintain its boundaries no matter what the topic while it differs in specific ways from fictional prose. The study also confirms that although the may appear to be the most frequent word, the zero article is the most frequent free morpheme in the English language. Keywords: Determiners; Predeterminers; Central Determiners; Postdeterminers; Genre; Research Article; RA; EST; Zero Article 1. Introduction The research article is the primary means of disseminating new scientific knowledge in the English language. -

Acquisition of the English Article System by Speakers of Polish in ESL and EFL Settings

Teachers College, Columbia University Working Papers in TESOL & Applied Linguistics, Vol. 4, No. 1 Acquisition of the English Article System by Speakers of Polish Acquisition of the English Article System by Speakers of Polish in ESL and EFL Settings Monika Ekiert1 Teachers College, Columbia University ABSTRACT This paper examines the second language (L2) developmental sequence of article acquisition by adult language learners in two different environments: English as a Second Language (ESL), and English as a Foreign Language (EFL). On the basis of an existing classification of English articles (a, the, zero), data on article usage were obtained from adult learners who were native speakers of Polish, a language that has no articles or article-like morphemes. Data analyses led to some limited conclusions about the order of acquisition of the English article system, and may contribute to a more detailed understanding of the nature of interlanguage representations. INTRODUCTION The English article system, which includes the indefinite article a(n), the definite article the, and the zero (or null) article,2 is one of the most difficult structural elements for ESL learners, causing even the most advanced non-native speakers of English (NNS) to make errors. These errors occur even when other elements of the language seem to have been mastered. According to Master (2002), the difficulty stems from three principle facts about the article system: (a) articles are among the most frequently occurring function words in English (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999), making continuous rule application difficult over an extended stretch of discourse; (b) function words are normally unstressed and consequently are very difficult, if not impossible, for a NNS to discern, thus affecting the availability of input in the spoken mode; and (c) the article system stacks multiple functions onto a single morpheme, a considerable burden for the learner, who generally looks for a one-form-one-function correspondence in navigating the language until the advanced stages of acquisition. -

Stylistic Differences Between Women and Men's Discourse in the Efl

REPUBLIC OF TURKEY ISTANBUL SABAHATTIN ZAIM UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING STYLISTIC DIFFERENCES BETWEEN WOMEN AND MEN’S DISCOURSE IN THE EFL CONTEXT MA THESIS Nadide AYBAR Istanbul August 2019 REPUBLIC OF TURKEY ISTANBUL SABAHATTIN ZAIM UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING STYLISTIC DIFFERENCES BETWEEN WOMEN AND MEN’S DISCOURSE IN THE EFL CONTEXT MA THESIS Nadide AYBAR Supervisor Asst. Prof. Dr. Emrah GÖRGÜLÜ Istanbul August 2019 i ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As I felt the full-hearted presence and sincerity of my family all through my life and this thesis process, I want to express my gratitude to my mother Nilhan, father İhsan, sister İpek Aybar and grandmother Nadide Çıvgın. Without their support, I would not be me, in both social life and academic life. I would like to give my special thanks to my supervisor Asst. Prof. Dr. Emrah Görgülü for his wise ideas, suggestions, genuine encouragement and support. I would like to express my thanks to my boyfriend Murat Can Çelik for helping me with my thesis and cheering me up in my stressful times. I also want to show my appreciation to my close friends, or with the exact definition, my second family, Merve Ertuğrul and Beyhan Yılmaz for encouraging me, for being with me each and every time. I thank Sinem Bayındır for showing me the way with help and her sharing. Lastly, my friend tribe members Duygu Doğrucan for her kindness and eagerness to help me and Fadime Çağlar for her full time motivation and smile that deserves a full hearted thanks and hug.