Ateetee, an Arsi Oromo Women's Sung Dispute Resolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jawar Mohammed Biography: the Interesting Profile of an Influential Man

Jawar Mohammed Biography: The Interesting Profile of an Influential Man Jawar Mohammed is the energetic, dynamic and controversial political face of the majority of young Ethiopian Oromo’s, who now have been given the green light to freely participate in the country’s changing political scene. It is evident that he now has a wide reaching network that spans across continents, namely, the Americas, Europe, and obviously Africa. Jawar has perfected the art of disseminating his views to reach his massive audience base through the expert use of the many media outlets, some of which he runs. His OMN (Oromia Media Network) was a constant source of information for those hoping to hear and watch the news from a TV broadcast that was not associated with the government. Furthermore, Jawar’s handling of Facebook with a following of no less than 1.2 million people, as well as, his skillful use of various other social media tools has helped firmly place him as an important and influential leader in today's ever changing Ethiopian political landscape. Jawar Mohammed: Childhood Jawar Mohammed was born in Dumuga (Dhummugaa), a small and quiet rural town located on the border of Hararghe and Arsi within the Oromia region of Ethiopia. His parents were considered to be one of the first in the area to have an inter-religious marriage. Some estimates claim that Dumuga, is largely an Islamic town, with over 90% of the population adhering to the Muslim faith. His father being a Muslim opted to marry a Christian woman, thereby; the young couple destroyed one of the age old social norms and customs in Dumuga. -

Oromo Indigenous Religion: Waaqeffannaa

Volume III, Issue IV, April 2016 IJRSI ISSN 2321 – 2705 Oromo Indigenous Religion: Waaqeffannaa Bedassa Gebissa Aga* *Lecturer of Human Rights at Civics and Ethical Studies Program, Department of Governance, College of Social Science, of Wollega University, Ethiopia Abstract: This paper discusses the African Traditional religion on earth. The Mande people of Sierra-Leone call him as with a particular reference to the Oromo Indigenous religion, Ngewo which means the eternal one who rules from above.3 Waaqeffannaa in Ethiopia. It aimed to explore status of Waaqeffannaa religion in interreligious interaction. It also Similar to these African nations, the Oromo believe in and intends to introduce the reader with Waaqeffannaa’s mythology, worship a supreme being called Waaqaa - the Creator of the ritual activities, and how it interrelates and shares with other universe. From Waaqaa, the Oromo indigenous concept of the African Traditional religions. Additionally it explains some Supreme Being Waaqeffanna evolved as a religion of the unique character of Waaqeffannaa and examines the impacts of entire Oromo nation before the introduction of the Abrahamic the ethnic based colonization and its blatant action to Oromo religions among the Oromo and a good number of them touched values in general and Waaqeffannaa in a particular. For converted mainly to Christianity and Islam.4 further it assess the impacts of ethnic based discrimination under different regimes of Ethiopia and the impact of Abrahamic Waaqeffannaa is the religion of the Oromo people. Given the religion has been discussed. hypothesis that Oromo culture is a part of the ancient Cushitic Key Words: Indigenous religion, Waaqa, Waaqeffannaa, and cultures that extended from what is today called Ethiopia Oromo through ancient Egypt over the past three thousand years, it can be posited that Waaqeffannaa predates the Abrahamic I. -

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008)

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008) ma, maa (O) why? HES37 Ma 1258'/3813' 2093 m, near Deresge 12/38 [Gz] HES37 Ma Abo (church) 1259'/3812' 2549 m 12/38 [Gz] JEH61 Maabai (plain) 12/40 [WO] HEM61 Maaga (Maago), see Mahago HEU35 Maago 2354 m 12/39 [LM WO] HEU71 Maajeraro (Ma'ajeraro) 1320'/3931' 2345 m, 13/39 [Gz] south of Mekele -- Maale language, an Omotic language spoken in the Bako-Gazer district -- Maale people, living at some distance to the north-west of the Konso HCC.. Maale (area), east of Jinka 05/36 [x] ?? Maana, east of Ankar in the north-west 12/37? [n] JEJ40 Maandita (area) 12/41 [WO] HFF31 Maaquddi, see Meakudi maar (T) honey HFC45 Maar (Amba Maar) 1401'/3706' 1151 m 14/37 [Gz] HEU62 Maara 1314'/3935' 1940 m 13/39 [Gu Gz] JEJ42 Maaru (area) 12/41 [WO] maass..: masara (O) castle, temple JEJ52 Maassarra (area) 12/41 [WO] Ma.., see also Me.. -- Mabaan (Burun), name of a small ethnic group, numbering 3,026 at one census, but about 23 only according to the 1994 census maber (Gurage) monthly Christian gathering where there is an orthodox church HET52 Maber 1312'/3838' 1996 m 13/38 [WO Gz] mabera: mabara (O) religious organization of a group of men or women JEC50 Mabera (area), cf Mebera 11/41 [WO] mabil: mebil (mäbil) (A) food, eatables -- Mabil, Mavil, name of a Mecha Oromo tribe HDR42 Mabil, see Koli, cf Mebel JEP96 Mabra 1330'/4116' 126 m, 13/41 [WO Gz] near the border of Eritrea, cf Mebera HEU91 Macalle, see Mekele JDK54 Macanis, see Makanissa HDM12 Macaniso, see Makaniso HES69 Macanna, see Makanna, and also Mekane Birhan HFF64 Macargot, see Makargot JER02 Macarra, see Makarra HES50 Macatat, see Makatat HDH78 Maccanissa, see Makanisa HDE04 Macchi, se Meki HFF02 Macden, see May Mekden (with sub-post office) macha (O) 1. -

20Th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies ፳ኛ የኢትዮጵያ ጥናት ጉባኤ

20th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies ኛ ፳ የኢትዮጵያ ጥናት ጉባኤ Regional and Global Ethiopia – Interconnections and Identities 30 Sep. – 5 Oct. 2018 Mekelle University, Ethiopia Message by Prof. Dr. Fetien Abay, VPRCS, Mekelle University Mekelle University is proud to host the International Conference of Ethiopian Studies (ICES20), the most prestigious conference in social sciences and humanities related to the region. It is the first time that one of the younger universities of Ethiopia has got the opportunity to organize the conference by itself – following the great example set by the French team of the French Centre of Ethiopian Studies in Addis Abeba organizing the ICES in cooperation with Dire Dawa University in 2012, already then with great participation by Mekelle University academics and other younger universities of Ethiopia. We are grateful that we could accept the challenge, based on the set standards, in the new framework of very dynamic academic developments in Ethiopia. The international scene is also diversifying, not only the Ethiopian one, and this conference is a sign for it: As its theme says, Ethiopia is seen in its plural regional and global interconnections. In this sense it becomes even more international than before, as we see now the first time a strong participation from almost all neighboring countries, and other non-Western states, which will certainly contribute to new insights, add new perspectives and enrich the dialogue in international academia. The conference is also international in a new sense, as many academics working in one country are increasingly often nationals of other countries, as more and more academic life and progress anywhere lives from interconnections. -

Download E-Book (PDF)

African Journal of Political Science and International Relations Volume 11 Number 9 September 2017 ISSN 1996-0832 ABOUT AJPSIR The African Journal of Political Science and International Relations (AJPSIR) is published monthly (one volume per year) by Academic Journals. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations (AJPSIR) is an open access journal that publishes rigorous theoretical reasoning and advanced empirical research in all areas of the subjects. We welcome articles or proposals from all perspectives and on all subjects pertaining to Africa, Africa's relationship to the world, public policy, international relations, comparative politics, political methodology, political theory, political history and culture, global political economy, strategy and environment. The journal will also address developments within the discipline. Each issue will normally contain a mixture of peer-reviewed research articles, reviews or essays using a variety of methodologies and approaches. Contact Us Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/AJPSIR Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/ Editors Dr. Thomas Kwasi Tieku Dr. Aina, Ayandiji Daniel Faculty of Management and Social Sciences New College, University of Toronto Babcock University, Ilishan – Remo, Ogun State, 45 Willcocks Street, Rm 131, Nigeria. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Prof. F. J. Kolapo Dr. Mark Davidheiser History Department University of Guelph Nova Southeastern University 3301 College Avenue; SHSS/Maltz Building N1G 2W1Guelph, On Canada Fort Lauderdale, FL 33314 USA. Dr. Nonso Okafo Graduate Program in Criminal Justice Dr. Enayatollah Yazdani Department of Political Science Department of Sociology Norfolk State University Faculty of Administrative Sciences and Economics University of Isfahan Norfolk, Virginia 23504 Isfahan Iran. -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: the Political Situation

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: The political situation Conducted 16 September 2019 to 20 September 2019 Published 10 February 2020 This project is partly funded by the EU Asylum, Migration Contentsand Integration Fund. Making management of migration flows more efficient across the European Union. Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 Background ............................................................................................................ 5 Purpose of the mission ........................................................................................... 5 Report’s structure ................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 6 Identification of sources .......................................................................................... 6 Arranging and conducting interviews ...................................................................... 6 Notes of interviews/meetings .................................................................................. 7 List of abbreviations ................................................................................................ 8 Executive summary .................................................................................................. 9 Synthesis of notes ................................................................................................ -

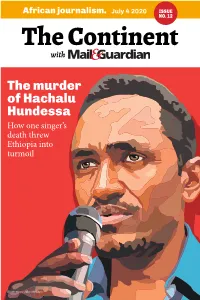

The Continent ISSUE 12

African journalism. July 4 2020 ISSUE NO. 12 The Continent with The murder of Hachalu Hundessa How one singer’s death threw Ethiopia into turmoil Illustration: John McCann Graphic: JOHN McCANN The Continent Page 2 ISSUE 12. July 4 2020 Editorial Abiy Ahmed’s greatest test When Abiy Ahmed became prime accompanying economic crisis, from minister of Ethiopia in 2018, he made which Ethiopia is not spared. the job look easy. Within months, he had released thousands of political All this occurs against prisoners; unbanned independent media and opposition groups; fired officials the backdrop of the implicated in human rights abuses; and global pandemic and made peace with neighbouring Eritrea. the accompanying Last year, he was rewarded with the economic crisis Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his efforts in brokering that peace. But the job of prime minister is never The future of 109-million Ethiopians easy, and now Abiy faces two of his now depends on what Abiy and his sternest tests – simultaneously. administration do next. The internet With the rainy season approaching, and information blackout imposed this Ethiopia is about to start filling the week, along with multiple reports of Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam brutality from state security forces and on the Blue Nile. No deal has been the arrests of key opposition leaders, are concluded with Egypt and Sudan, who a worrying sign that the government are both totally reliant on the waters of is resorting to repression to maintain the Nile River, and regional tensions are control. rising fast. Prime Minister Abiy was more than And then, this week, the assassination happy to accept the Nobel Peace Prize of Hachalu Hundessa (p15), an iconic last year, even though that peace deal singer and activist, sparked a wave of with Eritrea had yet to be tested (its key intercommunal conflict and violent provisions remain unfulfilled by either protests that threatens to upend side). -

Evidence of Social Media Blocking and Internet Censorship in Ethiopia

ETHIOPIA OFFLINE EVIDENCE OF SOCIAL MEDIA BLOCKING AND INTERNET CENSORSHIP IN ETHIOPIA Amnesty International is a global ABOUT OONI movement of more than 7 million The Open Observatory of Network Interference people who campaign for a (OONI) is a free software project under the Tor world where human rights are enjoyed Project that aims to increase transparency of internet censorship around the world. We aim to by all. empower groups and individuals around the world with data that can serve as evidence of internet Our vision is for every person to enjoy censorship events. all the rights enshrined in the Since late 2012, our users and partners around the Universal Declaration of Human world have contributed to the collection of millions of network measurements, shedding light on Rights and other international human multiple instances of censorship, surveillance, and rights standards. traffic manipulation on the internet. We are independent of any government, political We are independent of any ideology, economic interest or religion. government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Youth in Addis trying to get Wi-Fi Connection. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. ©Addis Fortune https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. -

Download the Pdf Version

Oromo Legacy Leadership PRESS RELEASE Oromoand Legacy Advocacy Leadership Association & Advocacy Association CONTACT US: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 07/23/2021 Senate Foreign Relations Committee Wants More Action to be Taken with African Allies FALLS CHURCH, VA (7/23/2021) – On July 20, 2021, U.S. Senator Jim Risch (R-Idaho), ranking member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, made the following statement regarding the nomination of assistant secretary for African Affairs, the Honorable Mary Catherine Phee: “The Biden Administration has stated that “Africa is a priority,” but it’s unclear where Africa fits in that priority list.” He continues, “First, I am troubled by the conflict and humanitarian situation in Tigray. However, I am concerned that the U.S. is so focused on the Tigray crisis that it is ignoring the significant challenges to peace and democracy we face across Ethiopia. This is a complex challenge, I get that. I look forward to hearing how we navigate Ethiopia’s challenges and the other crises across the Horn of Africa which is becoming more and more of a focus and a crisis.” Mr. Risch is clear in his understanding that this is not strictly an Ethiopian issue, but a regional and global issue. The “complexity” includes the imprisonment of political opponents, such as Jawar Mohammed. “Jawar, a founder of the United States-based Oromia Media Network, was an ally of Abiy and played a key role in coordinating the protests that catapulted him to power, before becoming a public critic of his administration.” Mohammed and others were imprisoned following the violence that erupted throughout Ethipia after the murder of singer-songwriter Hachalu Hundessa on June 29, 2020. -

Ethiopia 2020 Human Rights Report

ETHIOPIA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Ethiopia is a federal republic. The Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front, a coalition of four ethnically based parties, controlled the government until December 2019 when the coalition dissolved and was replaced by the Prosperity Party. In the 2015 general elections, the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front and affiliated parties won all 547 seats in the House of Peoples’ Representatives (parliament) to remain in power for a fifth consecutive five-year term. In 2018 former prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn announced his resignation to accelerate political reforms in response to demands from the country’s increasingly restive youth. Parliament then selected Abiy Ahmed Ali as prime minister to lead these reforms. Prime Minister Abiy leads the Prosperity Party. National and regional police forces are responsible for law enforcement and maintenance of order, with the Ethiopian National Defense Force sometimes providing internal security support. The Ethiopian Federal Police report to the Ministry of Peace. The Ethiopian National Defense Force reports to the Ministry of National Defense. The regional governments (equivalent to a U.S. state) control regional security forces, which are independent from the federal government. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Members of all security forces committed some abuses. Abiy’s assumption of office was followed by positive changes in the human rights climate. The government decriminalized political movements that in the past were accused of treason, invited opposition leaders to return and resume political activities, allowed peaceful rallies and demonstrations, enabled the formation and unfettered operation of political parties and media outlets, and carried out legislative reform of repressive laws. -

A Critical Hermeneutic Examination of the Dynamic of Identity Change in Christian Conversion Among Muslims in Ethiopia

A Critical Hermeneutic Examination of the Dynamic of Identity Change in Christian Conversion among Muslims in Ethiopia By Gary Ray Munson Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY In the subject of MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: DR. GERRIE LUBBE OCTOBER 2014 STATEMENT STUDENT NUMBER 4583-652-3 I declare that A Critical Hermeneutic Examination of the Dynamic of Identity Change in Christian Conversion among Muslims in Ethiopia Is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete reference. Signed: …………………….…………….. Date: ………………… Name: …………………………………… ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the many Ethiopian missionaries and church planters working among Muslims in Ethiopia who are sacrificing much to serve the Lord in this important work. They are an inspiration to all who know them. I also would like to thank my friend Musa who has explained much about Islam and the Muslim community of Ethiopia. Many thanks as well to Ato Gezahane Asmamaw, Director of Rift Valley Vision Project for his help and support in gathering many of the subjects of this research. Especially I thank my wife Felecia for her patience in my many months of study with tables full of books and articles filling the house. KEY TERMS C-5, Contextualization, Conversion, Identity, Narrative Identity, Muslim Outreach, church planting, Ethiopia, Ricoeur, Islam, Insider Movements Bible Quotations are taken from The Holy Bible: English Standard Version. 2001 Wheaton: Standard Bible Society, unless otherwise noted. ii DEDICATION This work is dedicate to my father, Ray Munson who went to be with Jesus during its writing.