Agale.: -See Agris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Branches with Vacant Lockers

Union Bank of India List of Branches having Vacant Lockers State District Branch Name Branch Address Branch Adrress 2 Phone Andaman-Nicobar Andaman PORT BLAIR 10.Gandhi Bhavan, Aberdeen Bazar, Port Blair, Dist. Andaman, 233344 Andhra Pradesh Anantapur HINDUPUR Ground Floor, Dhanalakshmi Road, SD-Hindupur, Dist.Anantapur, 227888 Andhra Pradesh Ananthpur KIRIKERA At & Post Kirikera, Tal. Hindupur, Dist. Anantpur, Andhra Pradesh, 247656 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor SRIKALAHASTI 6-166, Babu Agraharam, Srikalahasti Town, PO Srikalahasti, S.Dist. Srikalahasti, 222285 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor PUNGANUR Survey No. 129, First Floor, Opp. MPDO Office, Madanapalle Road, PO Punganur, 250794 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari RAMACHANDRAPURAM D No:11-01 6/7,Jayalakshmi Complex, Nr Matangi hotel, Opp Town Bank, Main Road, PO & SD 9494952586 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari EETHAKOTA FI Mani Road Eethakota, Near Vedureswaram, Ravulapalem Mandal, Dist: East Godavari, 09000199511 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari SAMALKOT D.No.11-2-24, Peddapuram Road, East Godavari District, Samalkot 2327977 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari MANDAPETA Door No. 34-16-7, Kamath Arcade, Main Road, Post Mandepeta, Dist. East Godavari, 234678 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari SARPAVARAM,KAKINADA DoorNo10-134,OPP Bhavani Castings,First Floor Sri Phani Bhushana Steel Pithapuram Road 2366630 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari TUNI Door No. 8-10-58, Opp. Kanyaka Parameswari Temple, Bellapu Veedhi, Tuni, Dist. 251350 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari VEDURESWARAM At&Post. Vedureswaram, Via Ravulapalem Mandal, Taluka Kothapet, Dist. East Godavari, 255384 KAMBALACHERUVU,RAJAHMUND Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Ground Floor,Yamuna Nilayam,DoorNo26-2-6, Koppisettyvari Street,PO Sriramnagar, 2555575 RY Andhra Pradesh Guntur RAVIPADU Door No.3-76 A, Main Road, PO Pavipadu (Guntur),S.Dist Narasaraopet 222267 Andhra Pradesh Guntur NARASARAOPET 909044 to 46, Bank Street, Arundelpet, P.O. -

Memoirs on the History, Folk-Lore, and Distribution of The

' *. 'fftOPE!. , / . PEIHCETGIT \ rstC, juiv 1 THEOLOGICAL iilttTlKV'ki ' • ** ~V ' • Dive , I) S 4-30 Sect; £46 — .v-..2 SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/memoirsonhistory02elli ; MEMOIRS ON THE HISTORY, FOLK-LORE, AND DISTRIBUTION RACESOF THE OF THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES OF INDIA BEING AN AMPLIFIED EDITION OF THE ORIGINAL SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF INDIAN TERMS, BY THE J.ATE SIR HENRY M. ELLIOT, OF THE HON. EAST INDIA COMPANY’S BENGAL CIVIL SEBVICB. EDITED REVISED, AND RE-ARRANGED , BY JOHN BEAMES, M.R.A.S., BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE ; MEMBER OP THE GERMAN ORIENTAL SOCIETY, OP THE ASIATIC SOCIETIES OP PARIS AND BENGAL, AND OF THE PHILOLOGICAL SOCIBTY OP LONDON. IN TWO VOLUMES. YOL. II. LONDON: TRUBNER & CO., 8 and 60, PATERNOSTER ROWV MDCCCLXIX. [.All rights reserved STEPHEN AUSTIN, PRINTER, HERTFORD. ; *> »vv . SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. PART III. REVENUE AND OFFICIAL TERMS. [Under this head are included—1. All words in use in the revenue offices both of the past and present governments 2. Words descriptive of tenures, divisions of crops, fiscal accounts, like 3. and the ; Some articles relating to ancient territorial divisions, whether obsolete or still existing, with one or two geographical notices, which fall more appro- priately under this head than any other. —B.] Abkar, jlLT A distiller, a vendor of spirituous liquors. Abkari, or the tax on spirituous liquors, is noticed in the Glossary. With the initial a unaccented, Abkar means agriculture. Adabandi, The fixing a period for the performance of a contract or pay- ment of instalments. -

List of Ph.D. Awarded

Geography Dept. B.H.U.: List of PhD awarded, 1958-2013 1 Updated: 19 August 2013: The 67th Geography Foundation Day B.H.U. Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, UP 221005. INDIA Department of Geography Doctoral Dissertation, Ph.D., in Geography: 1958 – 2013. No. Name of Scholar Title of the Doctoral Dissertation Awarded, & pub. year 1 2 3 4 1. Supervisor : Prof. Ram Lochan Singh (1946-1977) (late) 1. Shanti Lal Kayastha Himalayan Beas-Basin : A Study in Habitat, Economy 1958 and Society Pub. 1964 2. Radhika Narayan Ground Water Hydrology of Meerut District, U.P 1960 Mathur (earlier worked under Prof. Raj Nath, Geology Dept.) Pub. 1969 3. M. N. Nigam Urban Geography of Lucknow : (Submitted at Agra 1960 University) 4. S. L. Duggal Land Utilization Pattern in Moradabad District 1962 (submitted at Punjab University) 5. Vijay Ram Singh Land Utilization in the Neighbourhood of Mirzapur, U.P. 1962 Pub. 1970 6. Jagdish Singh Transport Geography of South Bihar 1962 Pub. 1964 7. Baccha Prasad Rao Vishakhapatanam : A Study in Geography of Port Town 1962 Pub. 1971 8. (Ms) Surinder Pannu Agro-Industrial Relationship in Saryupar Plain of U.P. 1962 9. Kashi N. Singh Rural Markets and Rurban Centres in Eastern U.P. 1963 10. Basant Singh Land Utilization in Chakia Tahsil, Varanasi 1963 11. Ram Briksha Singh Geography of Transport in U.P. 1963 Pub. 1966 12. S. P. Singh Bhagalpur : A Study in Regional Geography 1964 13. N. D. Bhattacharya Murshidabad : A Study in Settlement Geography 1965 14. Attur Ramesh TamiInadu Deccan: A Study. in Urban Geography 1965 15. -

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads - A Literature Review Anita Sharma CREATE PATHWAYS TO ACCESS Research Monograph No. 58 January 2011 University of Sussex Centre for International Education The Consortium for Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE) is a Research Programme Consortium supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Its purpose is to undertake research designed to improve access to basic education in developing countries. It seeks to achieve this through generating new knowledge and encouraging its application through effective communication and dissemination to national and international development agencies, national governments, education and development professionals, non-government organisations and other interested stakeholders. Access to basic education lies at the heart of development. Lack of educational access, and securely acquired knowledge and skill, is both a part of the definition of poverty, and a means for its diminution. Sustained access to meaningful learning that has value is critical to long term improvements in productivity, the reduction of inter- generational cycles of poverty, demographic transition, preventive health care, the empowerment of women, and reductions in inequality. The CREATE partners CREATE is developing its research collaboratively with partners in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The lead partner of CREATE is the Centre for International Education at the University of Sussex. The partners are: -

Short Code Rural 10.Xls

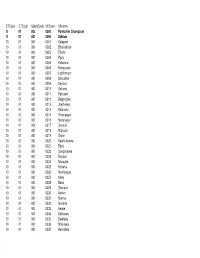

STCode DTCode SubdtCode VillCode Villname 10 01 000 0000 Pashchim Champaran 10 01 001 0000 Sidhaw 10 01 001 0001 Kalapani 10 01 001 0002 Bhaisalotan 10 01 001 0003 Tharhi 10 01 001 0004 Pipra 10 01 001 0005 Kotaraha 10 01 001 0006 Rampurwa 10 01 001 0007 Lachhmipur 10 01 001 0008 Daruabari 10 01 001 0009 Santpur 10 01 001 0010 Soharia 10 01 001 0011 Parsauni 10 01 001 0012 Balgangwa 10 01 001 0013 Jharharwa 10 01 001 0014 Shiunaha 10 01 001 0015 Champapur 10 01 001 0016 Narainapur 10 01 001 0017 Gonauli 10 01 001 0018 Malkauli 10 01 001 0019 Gorar 10 01 001 0020 Satchubanwa 10 01 001 0021 Pipra 10 01 001 0022 Songaharwa 10 01 001 0023 Dardari 10 01 001 0024 Misraulia 10 01 001 0025 Kotraha 10 01 001 0026 Naurangiya 10 01 001 0027 Kerai 10 01 001 0028 Berai 10 01 001 0029 Ghurauli 10 01 001 0030 Amhat 10 01 001 0031 Mohna 10 01 001 0032 Matiaria 10 01 001 0033 Amwa 10 01 001 0034 Katharwa 10 01 001 0035 Dewtaha 10 01 001 0036 Mahuawa 10 01 001 0037 Bankatwa 10 01 001 0038 Semra 10 01 001 0039 Harnatanr 10 01 001 0040 Mahdewa 10 01 001 0041 Bairiya Kalan 10 01 001 0042 Bairiya Khurd 10 01 001 0043 Chhatraul 10 01 001 0044 Garkatti 10 01 001 0045 Jarar 10 01 001 0046 Sinagahi 10 01 001 0047 Balua 10 01 001 0048 Bihar 10 01 001 0049 Belahwa 10 01 001 0050 Pachrukha 10 01 001 0051 Madanpur 10 01 001 0052 Rampurwa 10 01 001 0053 Rampur 10 01 001 0054 Naakar Rampur 10 01 001 0055 Jamunapur 10 01 001 0056 Pipra Dharauli 10 01 001 0057 Chegauna 10 01 001 0058 Binwaliya 10 01 001 0059 Dudhaura 10 01 001 0060 Karmaha 10 01 001 0061 Budhsar 10 01 -

CIN/BCIN Company/Bank Name Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L24110MH1978GOI020185 Prefill Company/Bank Name RASHTRIYA CHEMICALS AND FERTILIZERS LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 21-Sep-2017 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 801172.90 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) NO 3 4TH CROSS STREET SIVANTHIPATTI ROAD MAHARAJA IN300394-17247304- Amount for unclaimed and A KANNAN MARIMUTHU ARUMUGAM NAGAR WEST TIRUNELVELI INDIA Tamil Nadu 627011 0000 unpaid dividend 11.00 28-Oct-2023 AYIRAMVELIL,KARIMPADAM 12023900-00195809- Amount for unclaimed and A M MOHANAN NA CHENDAMANGALAM KOCHI INDIA Kerala 683512 RA00 unpaid dividend 27.50 28-Oct-2023 12044700-04899061- Amount for unclaimed and A MAREESWARAN ANDISAMY 19/160 KAMATI STREET NELLORE INDIA Andhra Pradesh 524001 RA00 unpaid dividend 8.80 28-Oct-2023 H. -

Studies in the History of Prostitution in North Bengal : Colonial and Post - Colonial Perspective

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF PROSTITUTION IN NORTH BENGAL : COLONIAL AND POST - COLONIAL PERSPECTIVE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TAMALI MUSTAFI Under the Supervision of PROFESSOR ANITA BAGCHI DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL RAJA RAMMOHUNPUR DARJEELING, PIN - 734013 WEST BENGAL SEPTEMBER, 2016 DECLARATION I declare that the thesis entitled ‘STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF PROSTITUTION IN NORTH BENGAL : COLONIAL AND POST - COLONIAL PERSPECTIVE’ has been prepared by me under the guidance of Professor Anita Bagchi, Department of History, University of North Bengal. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. Date: 19.09.2016 Department of History University of North Bengal Raja Rammohunpur Darjeeling, Pin - 734013 West Bengal CERTIFICATE I certify that Tamali Mustafi has prepared the thesis entitled ‘STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF PROSTITUTION IN NORTH BENGAL : COLONIAL AND POST – COLONIAL PERSPECTIVE’, of the award of Ph.D. degree of the University of North Bengal, under my guidance. She has carried out the work at the Department of History, University of North Bengal. Date: 19.09.2016 Department of History University of North Bengal Raja Rammohunpur Darjeeling, Pin - 734013 West Bengal ABSTRACT Prostitution is the most primitive practice in every society and nobody can deny this established truth. Recently women history is being given importance. Writing the history of prostitution in Bengal had already been started. But the trend of those writings does not make any interest to cover the northern part of Bengal which is popularly called Uttarbanga i.e. -

List of Nodal Officer

List of Nodal Officer Designa S.No tion of Phone (With Company Name EMAIL_ID_COMPANY FIRST_NAME MIDDLE_NAME LAST_NAME Line I Line II CITY PIN Code EMAIL_ID . Nodal STD/ISD) Officer 1 VIPUL LIMITED [email protected] PUNIT BERIWALA DIRT Vipul TechSquare, Golf Course Road, Sector-43, Gurgaon 122009 01244065500 [email protected] 2 ORIENT PAPER AND INDUSTRIES LTD. [email protected] RAM PRASAD DUTTA CSEC BIRLA BUILDING, 9TH FLOOR, 9/1, R. N. MUKHERJEE ROAD KOLKATA 700001 03340823700 [email protected] COAL INDIA LIMITED, Coal Bhawan, AF-III, 3rd Floor CORE-2,Action Area-1A, 3 COAL INDIA LTD GOVT OF INDIA UNDERTAKING [email protected] MAHADEVAN VISWANATHAN CSEC Rajarhat, Kolkata 700156 03323246526 [email protected] PREMISES NO-04-MAR New Town, MULTI COMMODITY EXCHANGE OF INDIA Exchange Square, Suren Road, 4 [email protected] AJAY PURI CSEC Multi Commodity Exchange of India Limited Mumbai 400093 0226718888 [email protected] LIMITED Chakala, Andheri (East), 5 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 6 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 7 NECTAR LIFE SCIENCES LIMITED [email protected] SUKRITI SAINI CSEC NECTAR LIFESCIENCES LIMITED SCO 38-39, SECTOR 9-D CHANDIGARH 160009 01723047759 [email protected] 8 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 9 SMIFS CAPITAL MARKETS LTD. -

Break-Up of Contesting Candidates

1- Dhanaha 1. No. and Name of the Constituency : : 1 - Dhanaha 2. Form Unique Serial Number (FUSN) Prefix : : KMQ 3. Type of Constituency (Gen/SC/ST) : : GEN 4. Name and Designation of the Returning Officer : Sri M.Jaya Deputy Director, Consolidation, West Champaran 5. Date of Poll 13/11/05 6. Date of Repoll (if any) - 7. Date of Commencement of Counting 22-Nov-2005 8. Date of Declaration of Result 22-Nov-2005 9. Data About Polling Stations : Regular Polling Stations - 129 Average No. of Electors Per Polling Station - 876 Auxilliary Polling Stations 9 Average No. of Voters Per Polling Station - 429 Total Polling Stations 138 10. Data About Candidates : Men Women Total No. of Nomination Filed : 11 0 11 No. of Nomination Rejected : 0 0 0 No. of Nomination found correct after scrutiny : 11 0 11 No. of Withdrawals : 0 0 0 No. of Contesting Candidates : 11 0 11 No. of Candidates who forfeited their deposits : 8 0 8 Break-Up of Contesting Candidates National Parties : 1 0 1 State Parties : 4 0 4 Registered (Unrecognised) Parties : 2 0 2 Independents : 4 0 4 11. Details about Electors : General Service Total Male 68,015 5 68,020 Female 52,823 3 52,826 Total 120,838 8 120,846 12. Details about Voters : General Postal Total Male 33,424 0 33,424 Female 25,829 0 25,829 Total 59,253 0 59,253 Rejected Votes 0 Missing Votes 0 1- Dhanaha 13. Names of Contesting Candidates and their details : Sl. Candidate Name & Address SC/ Sex Party Symbol Final No. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & Unreached People

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) AGWM Western edition I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

List of Common Service Centres Established in Uttar Pradesh

LIST OF COMMON SERVICE CENTRES ESTABLISHED IN UTTAR PRADESH S.No. VLE Name Contact Number Village Block District SCA 1 Aram singh 9458468112 Fathehabad Fathehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 2 Shiv Shankar Sharma 9528570704 Pentikhera Fathehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 3 Rajesh Singh 9058541589 Bhikanpur (Sarangpur) Fatehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 4 Ravindra Kumar Sharma 9758227711 Jarari (Rasoolpur) Fatehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 5 Satendra 9759965038 Bijoli Bah Agra Vayam Tech. 6 Mahesh Kumar 9412414296 Bara Khurd Akrabad Aligarh Vayam Tech. 7 Mohit Kumar Sharma 9410692572 Pali Mukimpur Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 8 Rakesh Kumur 9917177296 Pilkhunu Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 9 Vijay Pal Singh 9410256553 Quarsi Lodha Aligarh Vayam Tech. 10 Prasann Kumar 9759979754 Jirauli Dhoomsingh Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 11 Rajkumar 9758978036 Kaliyanpur Rani Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 12 Ravisankar 8006529997 Nagar Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 13 Ajitendra Vijay 9917273495 Mahamudpur Jamalpur Dhanipur Aligarh Vayam Tech. 14 Divya Sharma 7830346821 Bankner Khair Aligarh Vayam Tech. 15 Ajay Pal Singh 9012148987 Kandli Iglas Aligarh Vayam Tech. 16 Puneet Agrawal 8410104219 Chota Jawan Jawan Aligarh Vayam Tech. 17 Upendra Singh 9568154697 Nagla Lochan Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 18 VIKAS 9719632620 CHAK VEERUMPUR JEWAR G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 19 MUSARRAT ALI 9015072930 JARCHA DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 20 SATYA BHAN SINGH 9818498799 KHATANA DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 21 SATYVIR SINGH 8979997811 NAGLA NAINSUKH DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 22 VIKRAM SINGH 9015758386 AKILPUR JAGER DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 23 Pushpendra Kumar 9412845804 Mohmadpur Jadon Dankaur G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 24 Sandeep Tyagi 9810206799 Chhaprola Bisrakh G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. -

In Valmiki Tiger Reserve Terai Arc Landscape, Bihar Phase IV Monitoring - 2013 © Kamlesh K

STATUS OF TIGERS IN VALMIKI TIGER RESERVE Terai Arc Landscape, Bihar PHASE IV MONITORING - 2013 © WWF-India 2014 Published by WWF-India Any reproduction in full or part of this publication must mention the title and credit the mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. Citation Maurya, K. K. and Borah, J. 2013. Status of tigers in Valmiki Tiger Reserve,Terai Arc Landscape, Bihar, India. WWF-India. Note: This report presents the current status of tigers within Valmiki Tiger Reserve. Here we present minimum tiger numbers based on the camera trapping exercise within Valmiki. Given the contiguity between Valmiki and Chitwan National Park in Nepal, and tiger capture loca- tions from the study, these numbers may not exclusively represent the resident population from Valmiki. Future monitoring will robustly estimate population in this transboundary for- est complex. Cover Picture: Kamlesh K. Maurya/WWF-India Report Designed by: Aspire Design | aspiredesign.in A I AURYA / WWF-IND AURYA M © KAMLESH K. STATUS OF TIGERS IN VALMIKI TIGER RESERVE Terai Arc Landscape, Bihar PHASE IV MONITORING - 2013 FOREWORD Chief Minister of Bihar State III FOREWORD IV STATUS OF TIGERS IN VALMIKI TIGER RESERVE, TERAI ARC LANDSCAPE, BIHAR - PHASE IV MONITORING - 2013 Acknowledgements vii Executive Summary ix 1 Introduction 1.1 Tiger Monitoring in Valmiki Tiger Reserve 2 2 Study Area 2.1 Brief History 5 2.2 Location 5 2.3 Physical features 5 2.4 Climate 6 2.5 Flora & Fauna 7 2.6 Land Use Land Cover (LULC) 8 2.7 Human Population 8 3 Methods 3.1 Pre- Field Work 11 3.2