Dance Doc #2 Revised Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Commons @ Otterbein Nine

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein 2008-2009 Season Productions 2001-2010 5-21-2009 Nine Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/production_2008-2009 Part of the Acting Commons, Dance Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department, "Nine" (2009). 2008-2009 Season. 4. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/production_2008-2009/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Productions 2001-2010 at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2008-2009 Season by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OTTERBEIN COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE AND DANCE AND DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Present Nine Book by ARTHUR KOPIT Music & Lyrics by MAURY YESTON Adaptation from the Italian by Mario Fratti Broadway Production Directed by Tommy Tune Original Cast Album on Columbia Records & Tapes Directed by CHRISTINA KIRK Music Director DENNIS DAVENPORT Choreographer STELLA HIATT-KANE Set Design Costume Design ROB JOHNSON MARCIA HAIN Lighting Design DANA L. WHITE Stage Managed by KELSEY FARRIS May 21-24, 28-30, 2009 Fritsche Theatre at Cowan Hall Produced by special arrangement with SAMUEL FRENCH, INC. cast Guido............................................................................................. Cesar Villavicencio Young Guido..........................................................................................Conner -

Belvoir Terrace Staff 2018

Belvoir Terrace Staff 2018 Belvoir Terrace Staff 2018 Diane Goldberg Marcus - Director Educational Background D.M.A. City University of New York M.M. The Juilliard School B.M. Oberlin Conservatory Teaching/Working Experience American Camping Association Accreditation Visitor Private Studio Teacher - New York, NY Piano Instructor - Hunter College, New York, NY Vocal Coach Assistant - Hunter College, New York, NY Chamber Music Coach - Idyllwild School of Music, CA Substitute Chamber Music Coach - Juilliard Pre-College Division Awards/Publications/Exhibitions/Performances/Affiliations Married to Michael Marcus, Owner/Director of Camp Greylock, boys camp Becket, MA Independent School Liaison - Parents In Action, NYC Health & Parenting Association Coordinator - Trinity School, NYC American Camping Association Accreditation Visitor D.M.A. Dissertation: Piano Pedagogy in New York: Interviews with Four Master Teachers (Interviews with Herbert Stessin, Martin Canin, Gilbert Kalish, and Arkady Aronov) Teaching Fellowship - The City University of New York Honorary Scholarship for the Masters of Music Program – The Juilliard School The John N. Stern Scholarship - Aspen Music Festival Various Performances at: Paul Hall - Juilliard - New York Alice Tully Hall - New York City College - New York Berkshire Performing Arts Center, National Music Center - Lenox, MA WGBH Radio - Boston Reading Musical Foundation Museum Concert Series - Reading, PA Cancer Care Benefit Concert - Princeton, NJ Nancy Goldberg - Director Educational Background M.A. Harvard University -

We Finally See Rockwell, Williams in FX's First 'Fosse/Verdon' Trailer

We Finally See Rockwell, Williams in FX's First 'Fosse/Verdon' Trailer 02.25.2019 FX's upcoming eight-episode limited series, Fosse/Verdon, unpacks the turbulent five-decade relationship of legendary Hollywood director and choreographer, Bob Fosse (Sam Rockwell), and his wife, muse and star in her own right, Gwen Verdon (Michelle Williams). Their relationship starts as a director-star cliche and then evolves into something much more complicated as Fosse fuels his manic creativity with drugs, alcohol and sex. Verdon, meanwhile, reaches the height of her career as a Broadway triple threat and multiple Tony winner but watches Fosse stay in the spotlight as she fades into age and obscurity. Still, she remains his unrecognized collaborator even as their marriage unravels. Eventually, Fosse forges a connection with Ann Reinking (Margaret Qualley), an up-and-coming Broadway dancer who has all the talent and tenacity of a young Verdon. She hopes to follow in Verdon's footsteps, but may not have the stomach to put up with everything Fosse demands. Surrounding the couple are a coterie of fellow artists, friends, collaborators, and rivals: playwright and screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky (Norbert Leo Butz); former modern dancer- turned-homemaker Joan Simon (Aya Cash); Joan's husband, playwright Neil Simon (Nate Corddry); and theater producer and director Hal Prince (Evan Handler). The series is executive produced by Rockwell, Williams, Thomas Kail, Steven Levenson, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Joel Fields and George Stelzner. Levenson wrote the premiere episode, which is directed by Kail. Nicole Fosse, daughter of the couple, serves as key creative consultant, co-executive producer and keeper of the Verdon Fosse legacy. -

CHRISTOPHER WINDOM Director/Choreographer

CHRISTOPHER WINDOM Director/Choreographer www.ChristopherWindom.com Christopher Windom recently choreographed the visionary production of Les Misérables under the direction of Liesl Tommy at Dallas Theatre Center. He is currently serving as Associate Director for the national tour of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, directed and choreographed by Andy Blankenbuehler. He is also Movement Director for The Public Theatre Mobile Shakespeare production of Pericles directed by Rob Melrose. He served as Drama League Assistant Director on the Broadway revival of Pippin for Tony winning director Diane Paulus. He received the Dean Goodman Choice Award for best choreography for Ragtime at TheatreWorks in Palo Alto, California and received an Excellence Award for choreography and an Honorable Mention for directing Central Avenue Breakdown (NYMF.) Christopher has directed Moony's Kid Don't Cry by Tennessee Williams (Drama League). He’s directed and choreographed A Christmas Carol (Trinity Repertory Company), and Into The Woods (Webster University.) He directed The Three Times She Knocked by A.D. Penedo (Fringe NYC), which received a Critic's Pick and a Best of the Fest mention. He also directed Big River (Arrow Rock Lyceum Theatre), Chicago (Festival 56), Woyzeck, The Tempest, Our Country’s Good, (Brown/Trinity Rep), and Mo’ Reece and the Girls by Jackie Sibblies (New Plays Festival, Brown/Trinity Rep.) He choreographed Dessa Rose and Crowns (TheatreWorks), Oklahoma!, My Fair Lady (Maples Rep) Meet Me In St Louis, Chicago (Arrow Rock Lyceum -

Fred Ebb & Bob Fosse

Barry & Fran Weissler in association with Kardana/Hart Sharp Entertainment WELCOME. present LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, YOU ARE ABOUT TO SEE A Lyrics by Music By Book by STORY OF Fred Ebb John Kander Fred Ebb & Bob Fosse MURDER, Original Production Directed and Choreographed by Bob Fosse Based on the play by Maurine Dallas Watkins GREED, Supervising Music Director Music Director Rob Fisher Leslie Stifelman Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design John Lee Beatty William Ivey Long Ken Billington Sound Design Orchestrations Dance Music Arrangements CORRUPTION, Scott Lehrer Ralph Burns Peter Howard Script Adaptation Musical Coordinator Hair Design David Thompson Seymour Red Press David Brian Brown VIOLENCE, Casting Original Casting Duncan Stewart and Company Jay Binder Technical Supervisor Dance Supervisor Production Stage Manager Arthur Siccardi Gary Chryst David Hyslop Executive Producer Presented in Association with EXPLOITATION, Alecia Parker Broadway Across America General Manager Press Representative B.J. Holt Jeremy Shaffer The Publicity Office ADULTERY & Based on the presentation by City Center’s Encores!SM Choreography by Ann Reinking in the style of Bob Fosse TREACHERY Directed by Walter Bobbie – ALL THOSE THINGS WE HOLD Cast Recording on RCA Victor NEAR AND DEAR TO OUR HEARTS. AMY SPANGER STEPHANIE POPE This production isn’t just smoke and mirrors. It’s flesh and blood shaped by discipline and artistry into a parade of vital pulsing talent. If there’s any justice in this world (and Chicago insists there isn’t), audiences will be -

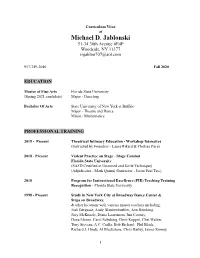

Michael Jablonski's CV

Curriculum Vitae of Michael D. Jablonski 51-34 30th Avenue #E4P Woodside, NY 11377 [email protected] 917-749-2040 Fall 2020 EDUCATION Master of Fine Arts Florida State University (Spring 2021 candidate) Major - Directing Bachelor Of Arts State University of New York at Buffalo Major - Theatre and Dance Minor - Mathematics PROFESSIONAL TRAINING 2019 - Present Theatrical Intimacy Education - Workshop Intensives (Instructed by Founders - Laura Rikard & Chelsea Pace) 2018 - Present Violent Practice on Stage - Stage Combat Florida State University (SAFD Certified in Unarmed and Knife Technique) (Adjudicator - Mark Quinn) (Instructor - Jason Paul Tate) 2018 Program for Instructional Excellence (PIE) Teaching Training Recognition - Florida State University 1998 - Present Study in New York City at Broadway Dance Center & Steps on Broadway, & other locations with various master teachers including: Josh Bergasse, Andy Blankenbuehler, Ann Reinking, Joey McKneely, Diana Laurenson, Jim Cooney, Dana Moore, Carol Schuberg, Dorit Koppel, Chet Walker, Tony Stevens, A.C. Ciulla, Bob Richard, Phil Black, Richard J. Hinds, Al Blackstone, Chris Bailey, James Kinney 1 2010 - Present One on One Studio - New York City On Camera Workshops (Selection by Audition) Instructors - Bob Krakower & Marci Phillips EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 2020 - 2021 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) (Culminations - Senior Seminar Course) (Instructor - Michael D. Jablonski) 2019 - 2020 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) Graduate Teaching Assistant (Performance I - Uta Hagen Acting Class) (Instructor of Record - Chari Arespacochaga) (Performance I Lab - Uta Hagen Workshop class) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. -

Lainie's Resume

LAINIE MUNRO AEA HR: AUBURN RED EYES: GREEN VOICE: BELT/SOPRANO HEIGHT: 5’4” WEIGHT: 120 RANGE: LOW F to HIGH C CELL: (917) 749-4849 [email protected] NATIONAL TOUR MY FAIR LADY TREVOR NUNN, DIR. SWING (PERFORMED ALL CAMERON MACKINTOSH/ MATTHEW BOURNE, CHOREO. FEATURED CHARACTER ROLES) NATIONAL THEATRE/ NETWORKS SHAUN KERRISON, RESIDENT DIR. INTERNATIONAL TOUR SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER LOREN VAN BRENK, DIR. FLO MANERO ROYAL CARIBBEAN PRODUCTIONS DIEGO ORENGO, CHOREO. THEATRE/REGIONAL OKLAHOMA! STARRING RUE MCCLANAHAN DANCE CAPT. /FEATURED DANCER BROADWAY SERIES OF CHARLOTTE 42ND STREET GEORGE MARTIN, DIR. PHYLLIS EUROPEAN TOUR JON ENGSTROM, CHOREO. AN INVITATION TO THE DANCE: GALA WITH NEW YORK POPS CHARLES STROUSE, DIR. FEATURED DANCER CARNEGIE HALL CHICAGO VELMA KELLY ALGONQUIN THEATRE, NJ A CHORUS LINE KRISTINE ALHAMBRA DINNER THEATRE SWEET CHARITY HELENE CPCC SUMMER THEATRE, NC ANYTHING GOES VIRTUE FIRESIDE PLAYHOUSE OF THEE I SING DIANA DEVEREAUX ALGONQUIN THEATRE, NJ TRAINING EDUCATION: B.F.A. IN MUSICAL THEATRE FROM FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY NEW YORK: BROADWAY DANCE CENTER, STEPS, ALVIN AILEY DANCE CENTER TAP: RANDY SKINNER, GERMAINE SALSBERG, BOB AUDY THEATRE: ANN REINKING, RANDY SKINNER, CHET WALKER BALLET: FINIS JHUNG, ROBERT ATWOOD, DORIT KOPPEL JAZZ: MICHAEL OWENS, MICHELE ASSAF VOICE TEACHER: PETER VAN DERICK VOICE COACH: BRAD GARSIDE SPECIAL SKILLS DIALECTS: BRITISH (RP), COCKNEY, AUSTRALIAN, SOUTHERN, NEW YORK, SPANISH VOICE: BELT/SOPRANO (LOW F TO HIGH C) AND EXCELLENT EAR FOR PART HARMONIES SPORTS: EQUESTRIAN- SKILLED IN DRESSAGE; CAN RIDE BOTH ENGLISH AND WESTERN ABILITIES: OUTSTANDING SWING SKILLS AND DANCE CAPT. SKILLS; EXCEPTIONAL MEMORY AND QUICK STUDY; EXTENSIVE DANCE CAPT. & ASST. CHOREOGRAPHER EXPERIENCE; SPECIAL GIFT FOR TEACHING NON-DANCERS HOW TO DANCE; EXCELLENT W/ CHILDREN . -

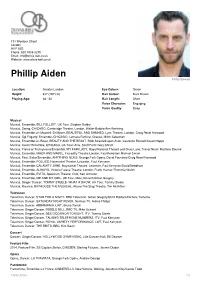

Phillip Aiden Philip Stewart

191 Wardour Street London W1F 8ZE Phone: 020 7439 3270 Email: [email protected] Website: www.olivia-bell.co.uk Phillip Aiden Philip Stewart Location: Greater London Eye Colour: Green Height: 6'2" (187 cm) Hair Colour: Dark Brown Playing Age: 36 - 50 Hair Length: Short Voice Character: Engaging Voice Quality: Deep Musical Musical, Ensemble, BILLY ELLIOT, UK Tour, Stephen Daldry Musical, Swing, CHICAGO, Cambridge Theatre, London, Walter Bobbie/Ann Reinking Musical, Ensemble u/s Maxwell, Dr Meyer, BEAUTIFUL AND DAMNED, Lyric Theatre, London, Craig Revel Horwood Musical, Sgt Fogarty/ Ensemble, CHICAGO, Larnaca Festival, Greece, Mitch Sebastian Musical, Ensemble u/s Beast, BEAUTY AND THE BEAST, RSC Stratford upon Avon, Laurence Boswell/Stuart Hopps Musical, Aaron/ Ensemble, CHICAGO, UK Tour/ Asia, Scott Faris/ Gary Chryst Musical, Prince of Transylvania/Ensemble, MY FAIR LADY, Royal National Theatre and Drury Lane, Trevor Nunn/ Matthew Bourne Musical, Ensemble, MACK AND MABEL, Piccadilly Theatre,London, Paul Kerryson/ Michael Smuin Musical, Feat. Sailor/Ensemble, ANYTHING GOES, Grange Park Opera, David Pountney/Craig Revel Horwood Musical, Ensemble, FOLLIES, Haymarket Theatre, Leicester, Paul Kerryson Musical, Ensemble, CALAMITY JANE, Haymarket Theatre, Leicester, Paul Kerryson/David Needham Musical, Ensemble, ALWAYS, Victoria Palace Theatre, London, Frank Hauser/Thommie Walsh Musical, Ensemble, EVITA, Spektrum Theatre, Oslo, Ken Urmston Musical, Ensemble, ME AND MY GIRL, UK Tour, Mike Ockrent/Gillian Gregory Musical, Singer/ Dancer, -

“Isn't It Swell... Nowadays?”: the Reception History of Chicago On

“Isn’t It Swell . Nowadays?”: The Reception History of Chicago on Stage and Screen A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Michael M. Kennedy BM, Butler University, 2004 MM, University of Hartford, 2008 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, PhD Abstract The musical Chicago represents an anomaly in Broadway history: its 1996 revival far surpassed the modest success of the original 1975 production. Despite the original production’s box-office accomplishments, it received disparaging reviews regarding the cynicism of the work’s content. The musical celebrates the crimes and acquittals of two murderesses, and is based on Maurine Dallas Watkins’s coverage as a Chicago Tribune reporter of two 1924 murder cases, from which she generated a 1926 Broadway play. The 1975 Broadway production of Chicago: A Musical Vaudeville utilized this historical source material to comment on contemporary American society, highlighting parallels between the U.S. justice system and the entertainment industry, which critics and audiences of the post-Watergate era deemed as too cynical. Although Chicago initially achieved a mixed reception, the revival’s producers made few changes to John Kander’s music, Fred Ebb’s lyrics, and Ebb and Bob Fosse’s book, aside from simplifying the title to Chicago: The Musical. This suggests that the musical’s newfound success can be attributed to a societal shift in the perception of its subject matter. With further success from Chicago’s 2002 film adaptation, the originally dark and sardonic material became a smash hit and found itself as mainstream entertainment at the turn of the millennium. -

A BED and a CHAIR: a New York Love Affair

Contact: Helene Davis [email protected]/212.354.7436 Helene Davis Public Relations: NORM LEWIS, JEREMY JORDAN join CYRILLE AIMÉE, BERNADETTE PETERS in A BED AND A CHAIR: A New York Love Affair New Stephen Sondheim/Wynton Marsalis Collaboration Presented by NEW YORK CITY CENTER & JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER Directed by John Doyle; Choreographed by Parker Esse November 13 – 17 at City Center Special Gala Benefit Performance on November 14 New York, N.Y., October 11, 2013 – Norm Lewis and Jeremy Jordan will join Cyrille Aimée and Bernadette Peters in Stephen Sondheim and Wynton Marsalis’s A BED AND A CHAIR: A New York Love Affair, a new musical event featuring Sondheim’s music arranged and performed by the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis. This Encores! Special Event, directed by frequent Sondheim collaborator John Doyle, with choreography by Parker Esse and musical supervision by David Loud, was conceived by Peter Gethers, Jack Viertel and John Doyle, and will run for seven performances, November 13 – 17 at City Center. The cast will include Cyrille Aimée, Jeremy Jordan, Norm Lewis and Bernadette Peters with dancers Meg Gillentine, Tyler Hanes, Grasan Kingsberry and Elizabeth Parkinson. A BED AND A CHAIR: A New York Love Affair, presented by the combined forces of City Center’s Encores! program and Jazz at Lincoln Center, celebrates love in New York and love of New York. Native Manhattanite Sondheim and adopted citizen Marsalis (originally from New Orleans) and compared musical notes on their shared passion for our city in a program that features more than two dozen Sondheim compositions, each piece newly re-imagined by the unique musical sensibility of Marsalis and performed by the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. -

Dance on TV: Fosse/Verdon by Mira Treatman

Photo courtesy of FX Networks Dance on TV: Fosse/Verdon by Mira Treatman Carol Burnett once called Gwen Verdon “the sweetest, and most talented dancer in the whole wide world.” In Fosse/Verdon, a mini- series produced by Lin-Manuel Miranda on FX, Verdon emerges as the heroine in contrast to a bitter, terse Robert [Bob] Fosse. The mini-series tracks the parallel biographies of the choreographer Fosse and the dancer-muse Verdon through the course of their courtship, marriage, divorce, and beyond. Fosse is the household name of the couple, but this series offers an equal amount of screen time and narrative space for actor Michelle Williams to portray Verdon as a full human being. Sam Rockwell as Fosse brings out the choreographer’s tortured pursuits of fame and glory. The best part of this series, by far, is the wickedly talented ensemble of concert and stage dancers who perform reconstructions of the classic Fosse numbers as created for the screen by choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler. This crew includes Georgina Pazcoguin in “Big Spender” from Sweet Charity, Heather Lang in “Mein Herr” from Cabaret, and Bianca Marroquín as Chita Rivera in Chicago, among other stand outs. These Broadway dance reconstructions serve as a delicious Fosse career retrospective spanning approximately 1955 to his death in 1987. Blankenbuehler does Fosse justice in translating them to the screen, although several, such as Cabaret and Chicago, have already been presented as films prior to their inclusion in this mini-series. Unsurprisingly, Fosse/Verdon is created for a general audience, perhaps for the period-drama market looking to fill the void left by Mad Men or The Marvelous Mrs. -

Cast Biographies

CAST BIOGRAPHIES BEN DANIELS (Paul Grayson) Ben Daniels is known for his impressive work in theatre, television and film. Daniels can most recently be seen on the small screen in “Jamaica Inn” (BBC), “The Paradise” (BBC) “Law and Order: UK,” the Netflix Original Series “House of Cards” alongside Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright, and Buckingham in The Hollow Crown, Richard III alongside Bendedict Cumberbatch. On the big screen he can most recently be seen in the films Luna, as the voice of Gareth in Locke alongside Tom Hardy. Previous film credits include Jack the Giant Slayer (Warner Bros.) Wipers Times, Doom (Universal Studios), Married Unmarried, Fanny and Elvis, Madeleine (Sony), I Want You, Passion in the Desert (New Line), and Beautiful Thing (Channel 4 Films). Previous television credits include, “Merlin,” “Women in Love,” “The Last Days of Lehman Brothers,” “The Passion,” “Lark Rise To Candleford ,” “Who Killed Mrs. De Ropp,” “The State Within,” “Ian Fleming: Bondmaker,” “Elizabeth – The Virgin Queen,” “MI-5,” “Miss Marple: What Mrs. Mcgillicuddy Saw,” “Real Men,” “Cutting It,” “Conspiracy,” “Aristocrats” “Silent Witness,” “Britannic,” “David,” “Outside Edge,” “Inspector Alleyn Mysteries: Death At The Bar,” “Truth Or Dare,” “Romeo And Juliet,” and “The Lost Language Of Cranes.” On stage, Daniels last starred in the Broadway revival of “Don’t Dress For Dinner” in 2012. Prior to this he appeared in “Haunted Child” and “Luise Miller” in 2011. He first starred on Broadway in “Les Liaisons Dangereuses » in 2008 for which he earned a Tony Award nomination for Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Play and was the winner of a TWA award for Outstanding Broadway Debut.