GIPE-167589.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustaining Agricultural Productivity and Enhancing Livelihoods Through

Sustaining agricultural productivity and enhancing livelihoods through optimization of crop and crop-associated biodiversity with emphasis on semi-arid tropical agroecosystems Proceedings of a workshop 23 - 25 September 2002 Patancheru, India Citation: Waliyar F, Collette L, and Kenmore P E. 2003. Beyond the gene horizon: sustaining agricultural productivity and enhancing livelihoods through optimization of crop and crop-associated biodiversity with emphasis on semi-arid tropical agroecosystems. Proceedings of a workshop, 23-25 September 2002, Patancheru, India. Patancheru 502 324, Andhra Pradesh, India: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), and viale delle Terme di Caracalla, Rome 00100, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 206 pp. ICRISAT ISBN 92-9066-457-6 Order code CPE 146 FAO ISBN 92-5-104942-4 Sponsors Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) with partial financial support from the Government of The Netherlands International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) Organizing Committee L Collette, F Waliyar, Murthi Anishetty, P E Kenmore, and I Radha Acknowledgements The Organizing Committee acknowledges the assistance of S D Hainsworth and T N G Sharma in the preparation of these proceedings. Further copies of these proceedings and the summary proceedings (CPE 143) of the meeting are available from: ICRISAT FAO Patancheru 502 324 and viale delle Terme di Caracalla Andhra Pradesh, India Rome 00100, Italy and also at www.icrisat.org -

Climate and Food Security

Climate and Food Security papers presented at the International Symposium on Climate Variability and Food Security in Developing Countries 5-9 February 1987 New Delhi, India organized by American Association for the Advancement of Science Indian National Science Academy International Rice Research Institute with support from Indian Council for Agricultural Research Indian Meteorological Department Indian Council of Scientific and Industrial Research India Department of Environment, Forest, and Wildlife 1989 International Rice Research Institute P.O. Box 933, 1099 Manila, Philipppines in collaboration with American Association for the Advancement of Science 1333 H. Street, N.W., Washington, D.C., 20005 U.S.A. The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) was established in 1960 by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations with the help and approval of the Government of the Philippines. Today IRRI is one ofthe I3 nonprofit international research and training centers supported by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). The CGIAR is sponsored by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank), and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The CGIAR consists of 50 donor countries. international and regional organizations, and private foundations. IRRI receives support, through the CGIAR, from a number of donors including the Asian Development Bank. the European Economic Community, the Ford Foun- dation, the International Development Research Centre, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the OPEC Special Fund, the Rockefeller Foundation, the United Nations Development Programme, the World Bank, and the international aid agencies ofthe following governments: Australia, Belgium, Brazil. Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, France. -

Documents List-Life Member 1 Dr

Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages CompleteDocuments List-Life Member 1 Dr. M.Z. Abdin Dr. (Mrs) Kamruza Zaman Ahmed Dr. R.C. Anand Deptt. of Biotechnology Sr. Scientific Asstt. Deptt. of Microbiology Faculty of Science, Department of Agronomy College of Basic Sciences Jamia Hamdard University Tocklai Experiment Station CCS Haryana Agril. University Hamdard Nagar, Jorhat – 785008, Hisar – 125004, Haryana New Delhi - 110062 Assam Dr. Ajay Dr. Rajiv Angrish Dr. Y.P. Abrol Sr. Scientist (Plant Physiology) Plant Physiologist/Assoc. Prof. 40, S.F.S., Haus Khas Apart. Environmental Soil Sciences Department of Botany Sri Aorubindo Marg Indian Institute of Soil Sciences CCS Haryana Agril. University New Delhi – 110016 (I.I.S.S.), Nabi Bagh, Barasia Road Hisar – 125004, Haryana Bhopal – 462038, M.P. Dr. S.J. AnkeGawda Dr. Bir Singh Afria Dr. Badre Alam Scientist Assoc. Professor Senior Scientist (Plant Physiology) Plant Physiology (Millet Physiologist) NRC for Agroforestry, Indian Institute of Species Res. Agriculture Research Station Near Pahuj Dam, Gwalior Road Cardamom Research Centre Durgapura- 302018, Jaipur Jhansi-284003 Appangala Modikeri - 571201 Rajasthan U.P. Karnataka Dr. A. Jauhar Ali Dr. M.M.R.K. Afridi Mrs. Edna Antony Asstt. Professor Khyber Afridi Compound C/o Dr. M.B. Doddmani Deptt. of Crop Improvement Friends Colony Deptt. of Environmental Sciences Agril. College and Research Instt. 4/417 Nagla Road, Dodhpur University of Agricultural Sciences Navalur, Kuttapattu Aligarh – 202002, U.P. Dharwad 580005, Karnataka Trichy – 620009, Tamil Nadu Dr. (Mrs.) M. Anuradha Dr. R.M. Agarwal Dr. S.A. Ali Div. of Crop Chemistry & Soil Sci., School of Studies in Botany Moh. -

Minor Millets in South Asia: Learnings from IFAD-NUS Project in India and Nepal

Minor Millets in South Asia Learnings from IFAD-NUS Project in India and Nepal Bhag Mal1, S. Padulosi2 and S. Bala Ravi3, editors 1 Bioversity International, Sub-regional Office for South Asia, NASC Complex, Pusa Campus, New Delhi 110 012, India 2 Bioversity International, Via dei Tre Denari, 472/a, 00057 Maccarese, Rome, Italy 3 M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Third Cross Street, Taramani Institutional Area, Chennai 600 113, India December, 2010 Citation Bhag Mal, S. Padulosi and S. Bala Ravi, editors. 2010. Minor Millets in South Asia: Learnings from IFAD-NUS Project in India and Nepal. Bioversity International, Maccarese, Rome, Italy and the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai, India. 185 p. Published by Bioversity International, Via dei Tre Denari 472/a, 00057 Maccarese, Rome, Italy. M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Third Cross Street, Taramani Institutional Area, Chennai 600113, India. ISBN – 978-92-9043-863-2 © 2010. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from Bioversity International and M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation. Photographs by S. Padulosi, Bioversity International, Maccarese, Rome, Italy, and S. Bala Ravi, MSSRF, Chennai, India. Printed at Malhotra Publishing House, B-6 DSIDC Complex, Kirti Nagar, New Delhi 110015, India. CONTENTS iii Contents Foreword v Preface vii Executive Summary 1 Introduction 13 Promoting Nutritious Millets for Enhancing Income and Improved Nutrition: 19 A Case Study from Tamil Nadu and Orissa S. Bala Ravi, S. Swain, D. Sengotuvel and N.R. Parida Enhancing Food Security and Income of the Rural Poor through 47 Technological Support for Improved Cultivation of Finger Millet: A Case Study from Southern Karnataka K.T. -

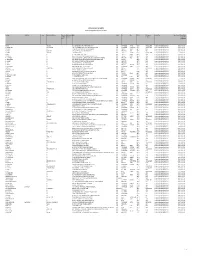

Transfered to IEPF

SATHAVAHANA ISPAT LIMITED unclaimed and unpaid dividend for the year 2008-09 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husband First Name Father/Husb Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Due(in Rs.) Proposed Date of and Middle Last Name Securities transfer to IEPF Name (DD-MON-YYYY) A ARUNA A RAJAGOPAL 17-71/1 RAJA MEDICALS B-KOTHAKOTA POST CHITTOOR DIST A P INDIA ANDHRA PRADESH CHITTOOR 517370 IN30051310356402 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid dividend 300.00 07-NOV-2016 A B R K VARA PRASAD MALLIKARJUNA RAO D NO 1 141 DWAJASTAMBAM STREET PALANGI POST UNDRAJAVARAM MANDAL INDIA ANDHRA PRADESH WEST GODAVARI 534216 IN30102221302854 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid dividend 30.00 07-NOV-2016 A B S MANIAM NA 25, VEERASAMY STREET GROUND FLOOR PURASAWALKAM MADRAS INDIA TAMIL NADU CHENNAI 600007 32168 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid dividend 150.00 07-NOV-2016 A C CHANDY CHANDY CHACKO 4/604 TULSI DHAM MAJIWADA PO THANE MAHARASHTRA INDIA MAHARASHTRA THANE 400607 6153 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid dividend 150.00 07-NOV-2016 A CHANDRAN S ANNAMALAI G 9 TAC NAGAR TUTICORIN INDIA TAMIL NADU TUTICORIN 628008 IN30177410302360 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid dividend 2.00 07-NOV-2016 A GANESH NA 61, EGMORE HIGH ROAD EGMORE CHENNAI INDIA TAMIL NADU CHENNAI 600008 39588 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid dividend 150.00 07-NOV-2016 A JAYA PRAKASH NA M-191 IX TH CROSS ST 3RD MAIN RD T V R NAGAR THIRUVANMIYUR CHENNAI INDIA TAMIL NADU CHENNAI 600041 18768 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid dividend 300.00 07-NOV-2016 -

Annual Report 2013-14

2013-14 Annual Report Nitte University NITTE UNIVERSITY (Declared as Deemed University under Section 3 of the UGC Act, 1956) Placed under Category ‘A’ by MHRD, Govt. of India Accredited with ‘A’ Grade by NAAC Deralakatte, Mangalore – 575 018, Karnataka 1 VISION To build a humane society through excellence in Education and Health care MISSION To develop Nitte University as a Centre of Excellence imparting quality education, generating competent, skilled manpower to face the scientific and social challenges, with a high degree of credibility, integrity, ethical standards and social concern 2 Annual Report 2013-14 For and on behalf of the Board of Management Nitte University (Deemed University under Section 3 of the UGC Act, 1956) Placed under Category ‘A’ by MHRD, Govt. of India Accredited with ‘A’ Grade by NAAC University Enclave, Medical Sciences Complex, Deralakatte, Mangalore – 575 018 Tel: 0824-2204300/01/02/03; Fax: 91-824-2204305 Website: www.nitte.edu.in E-mail: [email protected] 3 THE IMMORTAL Justice K. S. Hegde Founder, Nitte Education Trust Kowdoor Sadananda Hegde, born in Kowdoor village of Karnataka State, completed his early education at Karkala and Mangalore. Thereafter, he obtained a degree in Economics from the Presidency College, Madras and a degree in Law from the Government Law College, Madras. K.S.Hegde began legal practice at Karkala in 1936, after which he moved to Mangalore, where he was appointed as Public Prosecutor of South Kanara District in 1948. He was elected member of the First Council of States (now known as the Rajya Sabha). In 1954, he represented India at the General Assembly of the United Nations. -

Apr-17 to Mar-18 1St TEQIP News Letter.Pub

TEQIP-III / April 2017 – March 2018 / Volume– I P E S COLLEGE of Engineering Mandya—571 401, Karnataka (An Autonomous Institution affiliated to VTU, Belagavi ) Grant in Aid Institution (Govt. of Karnataka), Accredited by NBA, Approved by AICTE, New Delhi Chairman-BoG: Dr. Ramalingaiah Principal: Dr. V. Sridhar Vice Principal & TEQIP Coordinator : Dr. H V Ravindra Editor: Prof. B Dinesh Prabhu TEQIP - NEWS LETTER Vision: The Project, Third phase of Technical Education “P.E.S.C.E. shall be a leading institution imparting Quality Improvement Programme (referred to as quality engineering and management education de- TEQIP-III) is fully integrated with the Twelfth Five- veloping creative and socially responsible profession- year Plan objectives for Technical Education as a als” key component for improving the quality of Engi- Mission: neering Education in existing institutions to improve To provide state of the art infrastructure, motivate their policy, academic and management practices. the faculty to be proficient in their field of speciali- zation and adopt best teaching-learning practices. Project Objectives: To impart engineering and managerial skills Improving quality and equity in engineering institu- through competent and committed faculty, using tions in focus states outcome based educational curriculum. System-level initiatives to strengthen sector gov- To inculcate professional ethics, leadership quali- ernance and performance which include widening ties and entrepreneurial skills to meet socie- the scope of Affiliating Technical Universities tal needs. (ATUs) to improve their policy, academic and man- To promote research, product development and agement practices towards affiliated institutions, industry-institution interaction. and Quality Policy Twinning Arrangements to Build Capacity and Im- prove Performance of institutions and ATUs partici- Highly committed to provide quality, concurrent tech- pating in focus nical education and continuously strive to meet ex- pectations of stake holders. -

Annual Report 1996-97 ~~

ftl/{J-cc 753 ANNUAL REPORT 1996-97 ~~ DIRECTORATE OF RICE RESEARCH (INDIAN COUNCIL OF AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH) RAJENDRANAGAR HYDERABAD-500030 ~~~ (cql'lol£J ~ ~ qf{lSJC::) ,(1:JiO:<;:1~1,(, %<Usll< - 500 030 ISBN 81-7232-012-4 Correct CztatlOn Annual Report 1996-1997 DIrectorate of RlCe Research RaJendranagar Hyderabad-500030, IndIa Complied by APK Reddy, V Ba1asubramaman, AV Rao, NP Sarma, Mahabir Smgh K Rama Rao, SV Subbmah, IC Pasalu, U Prasada Rao MN Reddy, M Ilyas Ahmed Edlted by APK Reddy, and K Knshnmah Publlshed by Dr K Knshnmah, Project DIrector DIrectorate of RIce Research, Rajendranagar Hyderabad-500030 PrzntedAt HERITAGE PRINT SERVICES (P) LTO ,Hyderabad - 44 Ph +91 (40) 760 2453 7608604 <J1te ~ ~ 01 tk. ~~ 01 RICe ReJ.eaIzcIt, (~,tI1), 1~ eo. ~ RICe1~~) a bJ. co.-~ ~ teduu; 0I1UCe pM- ~~,~~,~~a.Hd~~mtk. cMeM 01 ~ IUCe eco.-~ a.Hd bJ. ~~ 01 ~ a.Hd ~ ReJ.eaIzcIt, ~ IuuMt ken ~ a.Hd ~ bJ. ~ tIeeJe ~ <lite ,4~ Rep<Yd ~ tk. ~~a.Hd adwdte4 kuu; ~ a.Hd tk. ~~ ~,tI1),1~ eo.-~ RICe 1~ P~, ~ ~ a.Hd Led, ~ m ~~, ~, Vrvueid, 1~, ,4~, god gCleHCe, Plaid P~, ~, Plaid P~, ,tI~ ~ a.Hd e~ <l~ eenbut <lite ~ a tk. tudco.me 01 tk. ~ 01 tk. ~01 ~RR a.Hd co.-~ ~ locaieJ ~ tk. ~ (!)~,tk.~wa4~~~~HUiedoHU~~ tudrud 0/UUded ~ ~~ 1996-97 iuJG ~ ~ w.e.'le ~ ~ cud!zd ~~ etUHHUitee a.Hd 18 ~ w.e.'le ~ ~ date ~~ ~ e~~~w.e.'leHUUkmtk.~eco.-~ ~ Uhe ~ ~ ped a.Hd ~ ~ /;vt ~ &uJ.p ~a.Hd~ ~ Me ~ bJ. ~ ~ ~ ~ UJdI" Naiuutd a.Hd 1~ ~ dJ-HlliJun, a; ~ ~ ku ken ~ ~ ~ ~~,~a.Hd~wIueJ"MeF~a.Hd~~ /;vt IUCe ~ a.Hd ~ gbuu«; ~ IJMe a kuu; Iuutt up at tk.