Northern Territory Government to Questions from the Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yukultji Napangati - Pintupi

YUKULTJI NAPANGATI - PINTUPI Represented by Utopia Art Sydney 983 Bourke St, Waterloo NSW 2017 Tel: 61 2 9319 6437 utopiaartsydney.com.au [email protected] Yukultji Napangati is a rising star of the Papunya Tula Artists. She first came to the notice of a wider audience through her inclusion in the 2005 Primavera exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia. She is renowned for her shimmering surfaces and subtle use of colour, however, as an artist, she continues to explore all possibilities. Born circa 1971 near Wilkinkarra (Lake Mackay), “Yukultji was still a young girl when her family group came out of the desert into Kiwirrkurra in 1984, making national headlines as the ‘last’ of the desert nomads to make ‘first contact’” (Vivien Johnson, 2008). Yukultji began painting for Papunya Tula Artists in 1996. Her work is included in significant public and private collections, including the Art Gallery of New South Wales, National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and the Hood Museum of Art, USA. Yukultji won the Wynne Prize at the AGNSW in 2018. Awards 2018 Winner ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of New South Wales 2013 Highly Commended ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of New South Wales 2012 Winner, ‘The Alice Prize’ 2011 Highly Commended, ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of New South Wales Solo Exhibitions 2020 Yukultji Napangati, Utopia Art Sydney, NSW 2019 Yukultji Napangati, Salon94, New York, USA 2014 Yukultji Napangati, Utopia Art Sydney, NSW Selected Group Exhibitions 2020 ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney -

Infrastructure Requirements to Develop Agricultural Industry in Central Australia

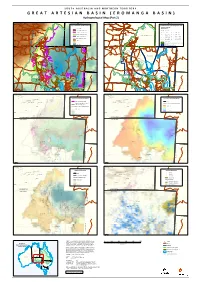

Submission Number: 213 Attachment C INFRASTRUCTURE REQUIREMENTS TO DEVELOP AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY IN CENTRAL AUSTRALIA 132°0'0"E 133°0'0"E 134°0'0"E 135°0'0"E 136°0'0"E 137°0'0"E Aboriginal Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & Water Control Land Trust Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Allocation fully economic Requirements Area (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) Karlantijpa 1000 20 Tennant ALT Creek + Warumungu $12m $3.94m Frewena ALT 2000 40 (Frewena) 19°0'0"S Frewena 19°0'0"S LIKKAPARTA Tennant Creek Karlantijpa ALT Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & Water Aboriginal Control Land Trust Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Area Allocation fully economic Requirements 20°0'0"S (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) 20°0'0"S Illyarne ALT 1500 30 Warrabri ALT 4000 100 $2.9m Western MUNGKARTA Murray $26m (Already Davenport Downs & invested via 1000 ABA $3.5m) Singleton WUTUNUGURRA Station CANTEEN CREEK Illyarne ALT Murray Downs and Singleton Stations ALI CURUNG 21°0'0"S 21°0'0"S WILLOWRA TARA Warrabri ALT AMPILATWATJA WILORA Ahakeye ALT (Community farm) ARAWERR IRRULTJA 22°0'0"S NTURIYA 22°0'0"S PMARA JUTUNTA YUENDUMU YUELAMU Ahakeye ALT (Adelaide Bore) A Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & B Water LARAMBA Control Aboriginal Land Water jobs when direct Infrastructure C District Trust (ALT) / Area Allocation fully economic Requirements Ahakeye ALT (6 Mile farm) (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) Ahakeye ALT Pine Hill Block B ENGAWALA community farm 30 5 ORRTIPA-THURRA Adelaide bore 1000 20 Ti-Tree $14.4m $3.82m Ahakeye ALT (Bush foods precinct) Pine Hill ‘B’ 1800 20 BushfoodsATITJERE precinct 70 5 6 mile farm 400 10 23°0'0"S 23°0'0"S PAPUNYA Potentia Potential Approximate Bore Field & HAASTS BLUFF Water Aboriginal Control Land Trust l Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Area Allocati fully economic Requirements on (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) A.S. -

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

Centring Anangu Voices

Report NR005 2017 Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education Sam Osborne John Guenther Lorraine King Karina Lester Sandra Ken Rose Lester Cen Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education. December 2017 Research conducted by Ninti One Ltd in conjunction with Nyangatjatjara College Dr Sam Osborne, Dr John Guenther, Lorraine King, Karina Lester, Sandra Ken, Rose Lester 1 Executive Summary Since 2011, Nyangatjatjara College has conducted a series of student and community interviews aimed at providing feedback to the school regarding student experiences and their future aspirations. These narratives have developed significantly over the last seven years and this study, a broader research piece, highlights a shift from expressions of social and economic uncertainty to narratives that are more explicit in articulating clear directions for the future. These include: • A strong expectation that education should engage young people in training and work experiences as a pathway to employment in the community • Strong and consistent articulation of the importance of intergenerational engagement to 1. Ground young people in their stories, identity, language and culture 2. Encourage young people to remain focussed on positive and productive pathways through mentoring 3. Prepare young people for work in fields such as ranger work and cultural tourism • Utilise a three community approach to semi-residential boarding using the Yulara facilities to provide access to expert instruction through intensive delivery models • Metropolitan boarding programs have realised patchy outcomes for students and families. The benefits of these experiences need to be built on through realistic planning for students who inevitably return (between 3 weeks and 18 months from commencement). -

Calendar of Events Unsafe Areas for Spectators

CALENDAR UNSAFE AREAS BUILD A EXTINGUISH OF EVENTS FOR SPECTATORS SAFE FIRE A CAMP FIRE Make sure there is a 4 x 4 metre clearing Remove slow burning logs and completely extuingish with water WHAT, WHERE & WHEN OF FINKE RACING VEHICLES CAN OVERSHOOT. Dig a hole about 90 cm in diameter and 30 cm State of Origin Screening - 6:00pm deep Shovel the boundary soil over the fire to completely cover it Wednesday 9th June - Lasseters Casino Use the soil that you have removed to make a Finke Street Party & Night Markets - 5:00pm FOR YOUR SAFETY WE INSIST YOU DON’T boundary for the fire Never leave a burning fire unattended Thursday 10th June - Todd Mall STAND/CAMP IN THE MARKED AREAS Build your fire in the hole Ensure all campfires are extinguished before Scrutineering - 4:00pm leaving the campsite Friday 11th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct Have some water nearby Prologue - 7:30am Saturday 12th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct Race Day 1 - 7:00am Under Section 74 of the Bushres Management Act Sunday 13th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct TIGHT CORNERS KEEP LEFT OR RIGHT 2016 (NT) if is an oence if a person leaves a re Race Day 2 - 7:30am unattended. Monday 14th June - Start/Finish Line Precinct No standing & camping zone No standing & camping zone Presentation Night - 6:30pm 4 Meters 90 cm 4 Meters Maximum penalty 500 penalty units or 5 years Monday 14th June - A/S Convention Centre imprisonment (1 penalty unit = $155) TIGHT CORNERS TURN AT CROSS ROAD MERCHANDISE No standing & camping zone No standing & camping zone ADMISSION FINKE -

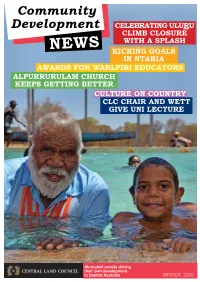

Community Development

Community Development CELEBRATING ULURU CLIMB CLOSURE WITH A SPLASH NEWS KICKING GOALS IN NTARIA AWARDS FOR WARLPIRI EDUCATORS ALPURRURULAM CHURCH KEEPS GETTING BETTER CULTURE ON COUNTRY CLC CHAIR AND WETT GIVE UNI LECTURE Aboriginal people driving their own development in Central Australia WINTER 2020 ANANGU CELEBRATE ULURU CLIMB 2 CLOSURE AND COMMUNITY PROJECTS Ngoi Ngoi Donald talking Anangu have used the Uluru climb with ABC journalist and closure to show off what they have CLC staff Patrick Hookey. achieved with their share of the national park’s gate money. On the afternoon before the celebration, “THAT MONEY, WE USE IT doubt about the pool’s popularity. traditional owners gave politicians, senior EVERYWHERE FOR GOOD The families visiting Mutitjulu for the climb public servants and selected media a special ONES: SWIMMING POOL, closure celebration and the midday heat tour of Mutitjulu’s pool and surrounding helped boost the number of swimmers. recreation area. BUSH TRIPS, DIALYSIS, LOTS OF GOOD THINGS Elder Reggie Uluru swapped his wheel chair The chief executive of the National Indigenous for a special lift to cool off in the pool with his Australians Agency, Ray Griggs and some of FOR COMMUNITY,” MS grandson Andre. his colleagues, then NT opposition leader Gary DONALD SAID. He was back refreshed as night descended Higgins and journalists from the ABC and the CLC chief executive Joe Martin-Jard and on Talinguru Nyakunytjaku (the sunrise Guardian learned that the project has so far community development manager Ian Sweeney viewing area), beating out the rhythm with invested 14 million dollars in more than 100 talked about the history, governance and future two ceremonial boomerangs as Anangu projects in communities across the region. -

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent Reviewer Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (Cth) 1999 16 April 2020 HEAD OFFICE 27 Stuart Hwy, Alice Springs POST PO Box 3321 Alice Springs NT 0871 1 PHONE (08) 8951 6211 FAX (08) 8953 4343 WEB www.clc.org.au ABN 71979 619 0393 ALPARRA (08) 8956 9955 HARTS RANGE (08) 8956 9555 KALKARINGI (08) 8975 0885 MUTITJULU (08) 5956 2119 PAPUNYA (08) 8956 8658 TENNANT CREEK (08) 8962 2343 YUENDUMU (08) 8956 4118 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 3 2. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... 4 3. OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 5 4. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 5. MODERNISING CONSULTATION AND INPUT ......................................................... 7 5.1. Consultation processes ................................................................................................... 8 5.2. Consultation timing ........................................................................................................ 9 5.3. Permits to take or impact listed threatened species or communities ........................... 10 6. CULTURAL HERITAGE AND SITE PROTECTION .................................................. 11 7. BILATERAL -

Family News 67

Family News Edition 67 Lexi Ward from Aputula and story on pg4 © Waltja Tjutangku Palyapayi Aboriginal Corporation “ doing good work with families” Postal: PO Box 8274 Alice Springs NT 0871 Location: 3 Ghan Rd Alice Springs NT 0870 Ph: (08) 8953 4488 Fax: (08) 89534577 Website: www.waltja.org.au Waltja Chairperson 2020ngka ngarangu watjil, watjilpa, tjilura, tjiluru nganampa Waltja tjutaku. Ngurra tjutanya patirringu marrkunutjananya ngurrangka nyinanytjaku wiya tawunukutu ngalya yankutjaku. Tjananya watjanu wiya, ngaanyakuntjaku Waltja kutjupa tjutangku tjana patikutu nyinangi Waltjangku, katjangku, yuntalpanku, tjamuku nyaakuntja wiya. Ngurra purtjingka nyinapaiyi tjutanya, Kapumantaku marrkunu tjananya nyinantjaku ngurrangka Tjanaya watjil watjilpa, nyinangi wiya nganana yuntjurringnyi tawunukatu yankutjaku mangarriku, yultja mantjintjaku Waltjalu? Tjanampa yiyanangi yultja tjuta ngurra winkikutu. Tjana yunparringu ngurra winkinya mangarriku Walytjalu yiyanutjangka. Walytjalu yilta tjananya puntura alpamilaningi. Panya Sharijnlu watjanutjangka. Yanangi warrkana tjutanya ngurra tjutakutu. Youth worker, NDIS, culture anta governance tjuta warrkanarripanya Walytjaku kimiti tjutanyalatju tjungurrikula miitingingka wankangi 12 times Member tjutangku miitingingka wangkangi AGM miitingi. Panya minta kuyangkulampa yangatjunu. AGM miitingi ngaraku March-tjingka (2021-ngngka) Nganana yuntjurrinyi minmya tjutaku ngurra tjutaku. Yukarraku, Ulkumanuku, nganana yuntjurringanyi. Palyaya nyinama ngurrangka Walytja tjuta kunpurringamaya. Palya Nangala. 2020 was a hard year, a sad year for people. The remote communities were locked down and no visiting each other. No shopping in Alice Springs. Everyone was crying for warm clothes and food. Oh we were too busy at Waltja clothes and food everywhere! Sending to every community. The rest of the year we were working with Sharijn to do all the programs, help the workers to go bush. Youth work, NDIS, culture and governance work. -

The Debilitating Aftermath of 10 Years of NT Intervention

18 Land Rights News • Northern Edition July 2017 • www.nlc.org.au The debilitating aftermath of 10 years of NT Intervention Jon Altman* n the April issue of Land Rights News I This is of special concern to Indigenous I do this because the Intervention was Both communities were established by celebrated the 30th anniversary of the people in the Northern Territory if the heavily promoted as a major project of the Commonwealth in 1959 and 1957 progressive and supportive Blanchard Commonwealth’s constitutional territory improvement and modernisation. Who can respectively and were colloquially referred report Return to Country: the Aboriginal powers remain in place and if, as in 2007, forget Malcolm Brough’s heroic call to to as ‘the Jewel of the Centre’ and ‘the Homelands Movement in Australia. And racial discrimination laws can be suspended ‘Stabilise, Normalise and Exit’ remote NT Jewel of the North’: these were to be the I wondered what celebration or reproach at the whim of the government of the day. communities, the delivery of what can be two demonstration communities where the the 10th anniversary of the Northern thought of as a domestic ‘Marshall Plan’ to Welfare Branch was going to show to all Third are the views expressed by Territory National Emergency Response, demonstrate the developmental powers of how modernisation and development could Indigenous community leaders who are the Intervention that was militaristically the Australian government in a jurisdiction and should be delivered. also subjects of the Intervention, several launched with extraordinary media fanfare where owing to a quirk of the Australian whom I heard present views in two events In 1972 when policy shifted to self- on 21 June 2007 might elicit. -

Alice Springs & Macdonnell Ranges Summary-01.Indd

Destination Management Plan Alice Springs and MacDonnell Ranges Region 2020 Summary Key Partners 1 Front Cover: Trephina Gorge Nature Park – East MacDonnell Ranges Back Cover: Hermannsburg Potters - Ntaria / Hermannsburg This Page: RT Tours2 Australia - Tjoritja / West MacDonnell National Park Contents Destination Management Plan role and process 5 Alice Springs and MacDonnell Ranges Region overview 6 Tourism in the Region Value of tourism in the Region Visitor market profile Trends in regional tourism Destination management planning for the Alice 12 Springs and MacDonnell Ranges Region Guiding principles Destination awareness Approach to developing visitor experiences in the Region Industry gaps and opportunities Action plan 15 Capacity building activities Facilitation of collaborative action Strategic product packaging and marketing Investment attraction initiatives Product development opportunities 19 Implementation 20 Reporting and reviews 22 Acronyms – References – Further information 22 3 Hermannsburg Historic Precinct – Ntaria / Hermannsburg 4 Destination Management Plan role and process The Department of Industry, Destination management requires Tourism and Trade has invested alignment and collaboration across the in destination management public, private and community sectors. It involves stakeholders from both the planning as part of a suite tourism and general industry sectors of actions following the contributing to the development development and release of priority experiences in the Alice of the NT’s Tourism Industry Springs and MacDonnell Ranges Strategy 2030. Destination Region. management ensures that Strategically planned and tourism is cohesively integrated implemented tourism experiences can be an economic driver, contributing into the economic, social, to the growth and development cultural and ecological fabrics of a Region through job creation, of a community, by considering investment attraction, and tourism growth holistically, infrastructure development. -

Chapter 9: Northern Territory Intervention and Indigenous Land

Chapter 9 187 Northern Territory intervention and Indigenous land The federal government on 21 June 2007 announced measures to tackle sexual abuse against Aboriginal children in the Northern Territory. The legislation it passed to implement the measures has significant implications for Aboriginal owned and controlled land. This chapter sets out the main provisions in that legislation that affect land. Concerns are identified. A more comprehensive analysis of the intervention in the Northern Territory and human rights is set out in my Social Justice Report 2007. In that report I provide an overview of the main human rights standards and legal obligations relevant to the government’s intervention. In this Native Title Report 2007 I focus on native title and land issues. The areas addressed are: n compulsory five-year leases; n town camps; n effects of other laws; and n rights in construction areas and infrastructure. Overview Legislation giving effect to the Australian Government’s intervention into Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory received Royal Assent1 on 17 August 2007. The main provisions dealing with the federal government’s acquisition of rights, titles and interests in land are contained in Part 4 of the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007 (Cth) (NTNER Act). There are also provisions dealing with infrastructure in Schedule 3 (Infrastructure) of the Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and Other Legislation Amendment (Northern Territory National Emergency Response and Other Measures) Act 2007 (Cth) (FCSIA(NTNER) Act). That Act amends the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (ALRA) inserting Part IIB (Statutory rights over buildings or infrastructure). -

Outstations Through Art: Acrylic Painting, Self‑Determination and the History of the Homelands Movement in the Pintupi‑Ngaanyatjarra Lands Peter Thorley1

8 Outstations through art: Acrylic painting, self-determination and the history of the homelands movement in the Pintupi-Ngaanyatjarra Lands Peter Thorley1 Australia in the 1970s saw sweeping changes in Indigenous policy. In its first year of what was to become a famously short term in office, the Whitlam Government began to undertake a range of initiatives to implement its new policy agenda, which became known as ‘self-determination’. The broad aim of the policy was to allow Indigenous Australians to exercise greater choice over their lives. One of the new measures was the decentralisation of government-run settlements in favour of smaller, less aggregated Indigenous-run communities or outstations. Under the previous policy of ‘assimilation’, living arrangements in government settlements in the Northern Territory were strictly managed 1 I would like to acknowledge the people of the communities of Kintore, Kiwirrkura and Warakurna for their assistance and guidance. I am especially grateful to Monica Nangala Robinson and Irene Nangala, with whom I have worked closely over a number of years and who provided insights and helped facilitate consultations. I have particularly enjoyed the camaraderie of my fellow researchers Fred Myers and Pip Deveson since we began working on an edited version of Ian Dunlop’s 1974 Yayayi footage for the National Museum of Australia’s Papunya Painting exhibition in 2007. Staff of Papunya Tula Artists, Warakurna Artists, Warlungurru School and the Western Desert Nganampa Walytja Palyantjaku Tutaku (Purple House) have been welcoming and have given generously of their time and resources. This chapter has benefited from discussion with Bob Edwards, Vivien Johnson and Kate Khan.