Copyright Yvonne Chen 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frédéric Vaysse-Knitter | Biography

ERIC BENOIST CONSEIL Frédéric Vaysse-Knitter | Biography "[Vaysse-Knitter] is clearly following in the tradition of Chopin, Debussy and Liszt. Starting with the first book of Debussy's Images, he achieved a shocking, almost physical beauty, ringing with boundless clarity. (...) The power, gravitas and harmonic richness of his interpretation [of Liszt's Funérailles] cannot fail to impress, as Vaysse-Knitter elicits from this solemn work a diversity of sound that would rival a grand symphony orchestra. Then finally, there is Debussy's Poisson d’or (...), fluidly played, with the delicate touch of overwhelming virtuosity." Bruno Serrou (June 2016) "Every descent into the self is also an ascension, an assumption, a glance toward the true external reality." This quote from Novalis perfectly expresses the quintessence of Vaysee-Knitter's nature – his playing is characterised by an extreme intensity and sense of vital urgency that grips the listener, as the piano under his hands sings melodies of introspection and transcendence. This duality partly explains the fascination that the music of Karol Szymanowski holds for him: For several years, Vaysse-Knitter has devoted himself to Szymanowski's entire piano oeuvre, as well as to the works of his contemporaries, yet all the while, he has remained particularly attached to modern day music. His Szymanowski solo recording was highly regarded among classical music publications, receiving 4 stars from Fonoforum, 5 stars from Piano News and a "Maestro" rating from Pianiste. Similarly, his subsequent album Szymanowski-Stravinsky (released by Aparté), which he recorded with violinist Solenne Païdassi was awarded a "Choc" by Classica, their highest recommendation, as well as 5/5 by Diapason and 10/10 by Klassik Heute. -

Gidon Kremer Oleg Maisenberg

EDITION SCHWETZINGER FESTSPIELE Bereits erschienen | already available: SCHUMANN SCHUBERT BEETHOVEN PROKOFIEV Fritz Wunderlich Hubert Giesen BEETHOVEN � BRAHMS SCHUbeRT LIEDERABEND Claudio Arrau ���� KLAVIERAB END � PIANO R E C ITAL WebeRN FRITZ WUNDERLICH·HUbeRT GIESEN CLAUDIO ARRAU BeeTHOVEN Liederabend 1965 Piano Recital SCHUMANN · SCHUBERT · BeeTHOVEN BeeTHOVEn·BRAHMS 1 CD No.: 93.701 1 CD No.: 93.703 KREISLER Eine große Auswahl von über 800 Klassik-CDs und DVDs finden Sie bei hänsslerCLassIC unter www.haenssler-classic.de, auch mit Hörbeispielen, Download-Möglichkeiten und Gidon Kremer Künstlerinformationen. Gerne können Sie auch unseren Gesamtkatalog anfordern unter der Bestellnummer 955.410. E-Mail-Kontakt: [email protected] Oleg Maisenberg Enjoy a huge selection of more than 800 classical CDs and DVDs from hänsslerCLASSIC at www.haenssler-classic.com, including listening samples, download and artist related information. You may as well order our printed catalogue, order no.: 955.410. E-mail contact: [email protected] DUO RecITAL Die Musikwelt zu Gast 02 bei den Schwetzinger Festspielen Partnerschaft, vorhersehbare Emigration, musikalische Heimaten 03 SERGEI PROKOFIev (1891 – 1953) Als 1952 die ersten Schwetzinger Festspiele statt- Gidon Kremer und Oleg Maisenberg bei den des Brüsseler Concours Reine Elisabeth. Zwei Sonate für Violine und Klavier fanden, konnten sich selbst die Optimisten unter Schwetzinger Festspielen 1977 Jahre später gewann er in Genua den Paganini- Nr. 1 f-Moll op. 80 | Sonata for Violine den Gründern nicht vorstellen, dass damit die Wettbewerb. Dazu ist – was Kremers Repertoire- eutsch eutsch D and Piano No. 1 in 1 F Minor, Op.80 [28:18] Erfolgsgeschichte eines der bedeutendsten deut- Als der aus dem lettischen Riga stammende, Überlegungen, seine Repertoire-Überraschungen D schen Festivals der Nachkriegszeit begann. -

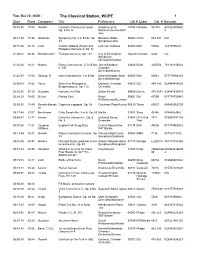

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Oct 20, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:00 Handel Concerto Grosso in D minor, Academy of St. 12704 Hanssler 98.918 401027600655 Op. 3 No. 5 Martin-in-the-Fields/Br 8 own 00:12:3037:36 Glazunov Symphony No. 8 in E flat, Op. Bavarian Radio 00963 Orfeo 093 201 N/A 83 Symphony/Jarvi 00:51:0608:15 Liszt Tearful Andante (Poetic and Leif Ove Andsnes 06005 EMI 57002 72435700223 Religious Harmonies, No. 9) 01:00:5108:35 Mendelssohn Trumpet Overture, Op. 101 City of Birmingham DownloadChandos 5235 n/a Symphony Orchestra/Gardner 01:10:2630:41 Mozart Piano Concerto No. 27 in B flat, Jarrett/Stuttgart 03926 ECM 1655/56 781182156524 K. 595 Chamber Orchestra/Davies 01:42:0717:06 Strauss, R. Horn Concerto No. 1 in E flat Damm/Dresden State 06500 EMI 69661 077776966120 Orchestra/Kempe 02:00:4314:22 Fauré Suite from Masques et Orpheus Chamber 04533 DG 449 186 028944918625 Bergamasques, Op. 112 Orchestra 02:16:0507:20 Debussy Nocturne in D flat Zoltan Kocsis 09850 Decca 478 3691 028947836919 02:24:25 35:00 Delius Florida Suite Royal 00853 EMI 47509 077774750981 Philharmonic/Beecham 03:00:5515:49 Rimsky-Korsak Capriccio espagnol, Op. 34 Cincinnati Pops/Kunzel 06630 Telarc 80657 089408065729 ov 03:17:44 27:57 Beethoven Cello Sonata No. 3 in A, Op. 69 Ma/Ax 01536 Sony 42446 07464424462 03:46:4113:17 Handel Concerto Grosso in F, Op. 6 Guildhall String 01887 RCA Red 7921 078635792126 No. -

Wednesday Playlist

October 23, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “Art and life are not two separate things.” — Gustav Mahler Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Chausson Poéme, Op. 25 Perlman/New York Philharmonic/Mehta DG 423 063 028942306325 Awake! 00:18 Buy Now! Brahms Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 Nakamatsu/Tokyo String Quartet Harmonia Mundi 8007558 093046755867 unavailable for 01:01 Buy Now! Mozart Horn Concerto No. 2 in E flat, K. 417 Slagter/New Amsterdam Sinfonietta/Markiz Radio Netherlands N/A sale Choir of St. Paul's Episcopal 01:15 Buy Now! Rorem Breathe on me Breath of God Pro Organo 7058 n/a Indianapolis/Boles 01:18 Buy Now! Bach, J.C. Sinfonia Concertante in A Camerata Budapest/Gmur Naxos 8.553085 730099408523 01:36 Buy Now! Rimsky-Korsakov Suite ~ The Tale of Tsar Saltan, Op. 57 Scottish National Orchestra/Jarvi Chandos 8327/8/9 N/A 01:59 Buy Now! Chopin Ballade No. 1 in G minor, Op. 23 Krystian Zimerman DG 423 090 028942309029 Symphony No. 3 in C minor, Op. 78 Reference 02:10 Buy Now! Saint-Saëns Kraybill/Kansas City Symphony/Stern 136 030911113629 "Organ" Recordings 02:46 Buy Now! Bach Flute Sonata in A, BWV 1032 Galway/Cunningham/Moll RCA Victor 68182 09026681822 03:00 Buy Now! Lortzing Overture ~ The Armor Maker Leipzig Radio Symphony/Guhl Hong Kong 8.220310 N/A 03:09 Buy Now! Moszkowski Piano Concerto in E, Op. 59 Lane/BBC Scottish Symphony/Maksymiuk Hyperion 66452 034571164526 03:47 Buy Now! Dvorak Romance in F minor, Op. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FOURTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 2, 2014, at 8:00 Friday, October 3, 2014, at 1:30 Saturday, October 4, 2014, at 8:30 Riccardo Muti Conductor Christopher Martin Trumpet Panufnik Concerto in modo antico (In one movement) CHRISTOPHER MARTIN First Chicago Symphony Orchestra performances Performed in honor of the centennial of Panufnik’s birth Stravinsky Suite from The Firebird Introduction and Dance of the Firebird Dance of the Princesses Infernal Dance of King Kashchei Berceuse— Finale INTERMISSION Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 3 in D Major, Op. 29 (Polish) Introduction and Allegro—Moderato assai (Tempo marcia funebre) Alla tedesca: Allegro moderato e semplice Andante elegiaco Scherzo: Allegro vivo Finale: Allegro con fuoco (Tempo di polacca) The performance of Panufnik’s Concerto in modo antico is generously supported by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute as part of the Polska Music program. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Andrzej Panufnik Born September 24, 1914, Warsaw, Poland. Died October 27, 1991, London, England. Concerto in modo antico This music grew out of opus 1.” After graduation from the conserva- Andrzej Panufnik’s tory in 1936, Panufnik continued his studies in response to the rebirth of Vienna—he was eager to hear the works of the Warsaw, his birthplace, Second Viennese School there, but found to his which had been devas- dismay that not one work by Schoenberg, Berg, tated during the uprising or Webern was played during his first year in at the end of the Second the city—and then in Paris and London. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

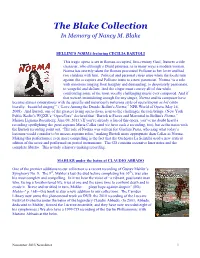

The Blake Collection in Memory of Nancy M

The Blake Collection In Memory of Nancy M. Blake BELLINI’S NORMA featuring CECILIA BARTOLI This tragic opera is set in Roman-occupied, first-century Gaul, features a title character, who although a Druid priestess, is in many ways a modern woman. Norma has secretly taken the Roman proconsul Pollione as her lover and had two children with him. Political and personal crises arise when the locals turn against the occupiers and Pollione turns to a new paramour. Norma “is a role with emotions ranging from haughty and demanding, to desperately passionate, to vengeful and defiant. And the singer must convey all of this while confronting some of the most vocally challenging music ever composed. And if that weren't intimidating enough for any singer, Norma and its composer have become almost synonymous with the specific and notoriously torturous style of opera known as bel canto — literally, ‘beautiful singing’” (“Love Among the Druids: Bellini's Norma,” NPR World of Opera, May 16, 2008). And Bartoli, one of the greatest living opera divas, is up to the challenges the role brings. (New York Public Radio’s WQXR’s “OperaVore” declared that “Bartoli is Fierce and Mercurial in Bellini's Norma,” Marion Lignana Rosenberg, June 09, 2013.) If you’re already a fan of this opera, you’ve no doubt heard a recording spotlighting the great soprano Maria Callas (and we have such a recording, too), but as the notes with the Bartoli recording point out, “The role of Norma was written for Giuditta Pasta, who sang what today’s listeners would consider to be mezzo-soprano roles,” making Bartoli more appropriate than Callas as Norma. -

In Search of Harmony: the Works by Andrzej Panufnik

MUSIC HistorY IN SEARCH OF HARMONY: THE WORKS BY ANDRZEJ PANUFNIK O.V. Sobakina Annotation. Andrzej Panufnik belongs to those composers, who were able to create their own musical language and technique of composing. The life way of prominent composer in postwar Poland and well-known conductor in Europe was dramatic: then he emigrated in England in 1954, his music turned out to be performed in the countries of the Eastern Europe. That’s why in Russia during decennials till now he didn’t share the fame, which the other Polish composers received. After some break in composing he realized in his works ideas, which were the most exiting for him and revealing the interaction between musical mentality, geometric schemes and nature’s phenomena. The features of Panufnik’s works consist in consequent development of traditions of the European music; using such traditional genres as symphony, concerto, overture, he interpreted them anew and created the new forms of musical structures. Differing in their individual construction of the forms, Panufnik’s symphonies are penetrated through really symphonic dramaturgy that emphasizes their attribution to classical symphonic traditions. In spite of pure originality and bold- ness of experiments, the works by Panufnik never lose the relationship with the Polish traditions and culture, which are revealed in the subjects of his music and also in the accordance of abstract perfection with the richness of emotional content. All this give us evidences of rare composer» creative talent and explains the incontestable interest to his music. In the Russian musicology the works by Panufnik had no analyzed with the exception of some articles of the author. -

Michael-Francis-Press-Kit.Pdf

_____________________________________________ M I C H A E L F R A N C I S Conductor _______________________________________ ichael Francis has quickly established himself 2014/2015 conduct return engagements with the BBC M as an international conductor creating National Orchestra of Wales, RTÉ National ongoing relationships with the world’s leading Symphony of Ireland, the Dresden Philharmonic, orchestras. He came to prominence as a conductor in and the symphonies of Oregon, Cincinnati, Ottawa January 2007 when he replaced an indisposed and Pittsburgh. Valery Gergiev for concerts with the London Symphony Orchestra during the BBC His European engagements have included the Gubaidulina festival at the Barbican Centre. Only English Chamber Orchestra, Orchestre de Chambre one month later, Francis was asked, this time with de Lausanne, Orquesta Sinfónica de RTVE Madrid, only two hours’ notice, to replace the Helsinki Philharmonic, the Mariinsky Orchestra, composer/conductor John Adams in a performance Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte-Carlo, and of his own works with the LSO at the Philharmonie Stuttgart Radio Symphony. Luxembourg and one short year later, January 2009, he replaced André Previn leading a German tour of Michael Francis’ 2010 debut with the San Francisco the Stuttgart Radio Symphony. Symphony quickly established a formidable relationship with the orchestra. He has now led Recently appointed Music Director for the Florida twenty-one different classical programs and three Orchestra in the Tampa Bay area, Michael Francis New Year’s Eve programmes with the orchestra. will assume his new role September 2015. He is also in his third season as Chief Conductor and Artistic In Asia, Michael Francis has worked with Japan Advisor to Sweden’s Norrköping Symphony Philharmonic, Tokyo Symphony, Hong Kong Orchestra and follows in the footsteps of Herbert Philharmonic, and National Taiwan Symphony with Blomstedt and Franz Welser-Möst each of who was upcoming returns to the Malaysia and Seoul Chief Conductor with the orchestra. -

Friday 14 February 2020 12:00 Music Through the Night 6:00 Daybreak

Spanish Songs - Alison Balsom (tpt), G450 - Kazuhito Yamashita (gtr), Phil/Daniel Harding (Virgin 5 45480) Gothenburg SO/Edward Gardner Tokyo String Quartet (RCA RD 60421) (EMI 3 53255) CHOPIN: Ballade No 1 in G minor R SMITH: Air Castles - Ryan Smith HILL: String Quartet No 3 in A minor, Op 23 - Krystian Zimerman (pno) (DG (accordian), Robyn Jaquiery (pno) Carnival - Dominion Quartet (Naxos 423 090) 8.570491) PUCCINI: Oh, saro la piu bella! - Tu, VIVALDI: Violin Concerto in G RV310 Friday 14 February 2020 BACH: Keyboard Concerto in G tu, amore? Tu?, from Manon Lescaut - Adrian Chandler (vln/dir), La Wq43/5 - Trevor Pinnock - Kiri Te Kanawa (sop), José Carreras, Serenissima (Avie AV 2106) 12:00 Music Through the (hpschd/dir), English Concert (CRD Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Night 3311) Bologna/Richard Cheetham (Decca 7.00 ZIPOLI arr Hunt: Elevazione - SZYMANOWSKI: Nocturne & 475 459) Gordon Hunt (ob/dir), Niklass Tarantella Op 28 - Tasmin Little (vln), KOEHNE: Way Out West - Diana HAYDN: Cello Concerto No 2 in D Veltman (cello), Norrköping SO (BIS Piers Lane (pno) (Chandos CHAN Doherty (ob), Sinfonia HobVIIb/2 (3) - Gautier Capuçon CD 5017) 10940) Australis/Mark Summerbell (ABC 980 (cello), Mahler CO/Daniel Harding LISZT transcr Grainger: Hungarian RACHMANINOV: Prelude No 4 in E 046) (Virgin 5 45560) Fantasy S123 - Ivan Hovorun (pno), Minor, Op 32 - Colin Horsley (pno) DUSSEK: Sinfonia in A - Helsinki Royal Northern College of Music (Atoll ACD 442) Baroque Orch/Aapo Häkkinen RACHMANINOV: Symphony No 2 in Wind Orch/Clark Rundell (Chandos -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

The Blake Collection in Memory of Nancy M

The Blake Collection In Memory of Nancy M. Blake BELLINI’S NORMA featuring CECILIA BARTOLI This tragic opera is set in Roman-occupied, first-century Gaul, features a title character, who although a Druid priestess, is in many ways a modern woman. Norma has secretly taken the Roman proconsul Pollione as her lover and had two children with him. Political and personal crises arise when the locals turn against the occupiers and Pollione turns to a new paramour. Norma “is a role with emotions ranging from haughty and demanding, to desperately passionate, to vengeful and defiant. And the singer must convey all of this while confronting some of the most vocally challenging music ever composed. And if that weren't intimidating enough for any singer, Norma and its composer have become almost synonymous with the specific and notoriously torturous style of opera known as bel canto — literally, ‘beautiful singing’” (“Love Among the Druids: Bellini's Norma,” NPR World of Opera, May 16, 2008). And Bartoli, one of the greatest living opera divas, is up to the challenges the role brings. (New York Public Radio’s WQXR’s “OperaVore” declared that “Bartoli is Fierce and Mercurial in Bellini's Norma,” Marion Lignana Rosenberg, June 09, 2013.) If you’re already a fan of this opera, you’ve no doubt heard a recording spotlighting the great soprano Maria Callas (and we have such a recording, too), but as the notes with the Bartoli recording point out, “The role of Norma was written for Giuditta Pasta, who sang what today’s listeners would consider to be mezzo-soprano roles,” making Bartoli more appropriate than Callas as Norma.