That Which You Love

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

“Am I Not of Those Who Reared / the Banner of Old Ireland High?” Triumphalism, Nationalism and Conflicted Identities in Francis Ledwidge’S War Poetry

Romp /1 “Am I not of those who reared / The banner of old Ireland high?” Triumphalism, nationalism and conflicted identities in Francis Ledwidge’s war poetry. Bachelor Thesis Charlotte Romp Supervisor: dr. R. H. van den Beuken 15 June 2017 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Radboud University Nijmegen Romp /2 Abstract This research will answer the question: in what ways does the poetry written by Francis Ledwidge in the wake of the Easter Rising reflect a changing stance on his role as an Irish soldier in the First World War? Guy Beiner’s notion of triumphalist memory of trauma will be employed in order to analyse this. Ledwidge’s status as a war poet will also be examined by applying Terry Phillips’ definition of war poetry. By remembering the Irish soldiers who decided to fight in the First World War, new light will be shed on a period in Irish history that has hitherto been subjected to national amnesia. This will lead to more complete and inclusive Irish identities. This thesis will argue that Ledwidge’s sentiments with regards to the war changed multiple times during the last year of his life. He is, arguably, an embodiment of the conflicting loyalties and tensions in Ireland at the time of the Easter Rising. Key words: Francis Ledwidge, Easter Rising, First World War, Ireland, Triumphalism, war poetry, loss, homesickness Romp /3 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 History and Theory ................................................................................................... -

Visual Gender Separation During the Troubles

Irish Communication Review Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 6 July 2020 Posters, Handkerchiefs and Murals: Visual Gender Separation During the Troubles Bradley Rohlf Mount Aloysius College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr Part of the Communication Commons, History of Gender Commons, Visual Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rohlf, Bradley (2020) "Posters, Handkerchiefs and Murals: Visual Gender Separation During the Troubles," Irish Communication Review: Vol. 17: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr/vol17/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Current Publications at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Communication Review by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Irish Communications Review vol 17 (2020) Posters, handkerchiefs and murals: Visual gender separation during the Troubles Bradley Rohlf, Mount Aloysius College (Pennsylvania) Abstract The Troubles in Northern Ireland provide a complex and intriguing topic for many scholars in various academic disciplines. Their violence, publicity and tragedy are common themes that elicit a plethora of emotional responses throughout the world. However, the very intimate nature of this conflict creates a much more complex system of friends, foes and experiences for those involved. While the very heart of the Irish nationalist movement is founded on liberal and progressive concepts such as socialism and equality, the media associated with it sometimes promote tradition and conservatism, especially regarding gender. -

A League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

THE ROLE OF THE GAELIC LEAGUE THOMAS MacDONAGH PATRICK PEARSE EOIN MacNEILL A League of extraordinary gentlemen Gaelic League was breeding ground for rebels, writes Richard McElligott EFLECTING on The Gaelic League was The Gaelic League quickly the rebellion that undoubtedly the formative turned into a powerful mass had given him nationalist organisation in the movement. By revitalising the his first taste of development of the revolutionary Irish language, the League military action, elite of 1916. also began to inspire a deep R Michael Collins With the rapid decline of sense of pride in Irish culture, lamented that the Easter Rising native Irish speakers in the heritage and identity. Its wide was hardly the “appropriate aftermath of the Famine, many and energetic programme of time for memoranda couched sensed the damage would be meetings, dances and festivals in poetic phrases, or actions irreversible unless it was halted injected a new life and colour DOUGLAS HYDE worked out in similar fashion”. immediately. In November 1892, into the often depressing This assessment encapsulates the Gaelic scholar Douglas Hyde monotony of provincial Ireland. the generational gulf between delivered a speech entitled ‘The Another significant factor participation in Gaelic games. cursed their memory”. Pearse the romantic idealism of the Necessity for de-Anglicising for its popularity was its Within 15 years the League had was prominent in the League’s revolutionaries of 1916 and the Ireland’. Hyde pleaded with his cross-gender appeal. The 671 registered branches. successful campaign to get Irish military efficiency of those who fellow countrymen to turn away League actively encouraged Hyde had insisted that the included as a compulsory subject would successfully lead the Irish from the encroaching dominance female participation and one Gaelic League should be strictly in the national school system. -

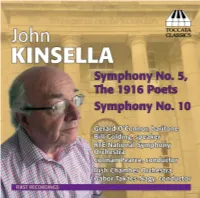

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

A Poet's Rising

A POET’S RISING A POET’S RISING In 2015 the Irish Writers Centre answered the Arts Council’s Open Call for 2016 and A Poet’s Rising was born. Our idea was this: to commission six of Ireland’s most eminent poets to respond through poetry focusing on a key historical figure and a particular location associated with the Rising. The poets would then be filmed in each discreet location and made permanent by way of an app, freely available for download. The resulting poems are beautiful, important works that deserve to be at the forefront of the wealth of artistic responses generated during this significant year in Ireland’s history. We are particularly proud to be producing this exceptional oeuvre in the year of our own 25th anniversary since the opening of the Irish Writers Centre. • James Connolly at Liberty Hall poem by Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin • Pádraig Pearse in the GPO poem by Paul Muldoon • Kathleen Lynn in City Hall poem by Jessica Traynor • The Ó Rathaille at O’Rahilly Parade poem by Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill • Elizabeth O’Farrell in Moore Lane poem by Theo Dorgan • The Fallen at the Garden of Remembrance poem by Thomas McCarthy We wish to thank Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Paul Muldoon, Jessica Traynor, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Theo Dorgan and Thomas McCarthy for agreeing to take part and for their resonant contributions, and to Conor Kostick for writing the historical context links between each poem featured on the app. A special thanks goes to Colm Mac Con Iomaire, who has composed a beautiful and emotive score, entitled ‘Solasta’, featured throughout the app. -

Speech on Joseph Mary Plunkett, Delivered at Stonyhurst College Thursday, 29Th September, 2016

Speech on Joseph Mary Plunkett, delivered at Stonyhurst College Thursday, 29th September, 2016 As Ireland commemorates the centenary of the Easter Rising — the event that sparked a popular movement towards independence from the United Kingdom one hundred years ago this year — the tendency has been to focus, perhaps somewhat simplistically, on the history of the participants and of the event itself. But in the Easter Rising we find that history was born in literature, and reality in text. With the Celtic Revival in its latter days by 1916, and the rediscovery of national heroes from ancient myth, such as Cuchulain, permeating the popular imagination, it should not seem too surprising that a headmaster, a university professor, and an assortment of poets saw themselves — and became — the champions of Irish freedom. As the historian Standish O’Grady prophetically declared in the late nineteenth century: ‘We have now a literary movement, it is not very important; it will be followed by a political movement that will not be very important; then must come a military movement that will be important indeed.’1 The ideas crafted in the study took fire in the streets in 1916, and Joseph Mary Plunkett — poet, aesthete, military strategist, and rebel — offers a fascinating study of this nexus of thought and action. Plunkett is often mythologized as the hero who wed his sweetheart on the eve of his execution in May 1916, but I would like to broaden this narrative by framing this evening’s talk around not one but three women who profoundly shaped Plunkett’s life, and who are the subject of many poems he wrote, some of which I would like to share with you this evening. -

Joseph Mary Plunkett - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Joseph Mary Plunkett - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Joseph Mary Plunkett(21 November 1887 – 4 May 1916) Joseph Mary Plunkett (Irish: Seosamh Máire Pluincéid) was an Irish nationalist, poet, journalist, and a leader of the 1916 Easter Rising. <b>Background</b> Plunkett was born at 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street in one of Dublin's most affluent neighborhoods. Both his parents came from wealthy backgrounds, and his father, George Noble Plunkett, had been made a papal count. Despite being born into a life of privilege, young Joe Plunkett did not have an easy childhood. Plunkett contracted tuberculosis at a young age. This was to be a lifelong burden. His mother was unwilling to believe his health was as bad as it was. He spent part of his youth in the warmer climates of the Mediterranean and north Africa. He was educated at the Catholic University School (CUS) and by the Jesuits at Belvedere College in Dublin and later at Stonyhurst College, in Lancashire, where he acquired some military knowledge from the Officers' Training Corps. Throughout his life, Joseph Plunkett took an active interest in Irish heritage and the Irish language, and also studied Esperanto. Plunkett was one of the founders of the Irish Esperanto League. He joined the Gaelic League and began studying with Thomas MacDonagh, with whom he formed a lifelong friendship. The two were both poets with an interest in theater, and both were early members of the Irish Volunteers, joining their provisional committee. Plunkett's interest in Irish nationalism spread throughout his family, notably to his younger brothers George and John, as well as his father, who allowed his property in Kimmage, south Dublin, to be used as a training camp for young men who wished to escape conscription in England during World War I. -

Irish Working-Class Poetry 1900-1960

Irish Working-Class Poetry 1900-1960 In 1936, writing in the Oxford Book of Modern Verse, W.B. Yeats felt the need to stake a claim for the distance of art from popular political concerns; poets’ loyalty was to their art and not to the common man: Occasionally at some evening party some young woman asked a poet what he thought of strikes, or declared that to paint pictures or write poetry at such a moment was to resemble the fiddler Nero [...] We poets continued to write verse and read it out at the ‘Cheshire Cheese’, convinced that to take part in such movements would be only less disgraceful than to write for the newspapers.1 Yeats was, of course, striking a controversial pose here. Despite his famously refusing to sign a public letter of support for Carl von Ossietzky on similar apolitical grounds, Yeats was a decidedly political poet, as his flirtation with the Blueshirt movement will attest.2 The political engagement mocked by Yeats is present in the Irish working-class writers who produced a range of poetry from the popular ballads of the socialist left, best embodied by James Connolly, to the urban bucolic that is Patrick Kavanagh’s late canal-bank poetry. Their work, whilst varied in scope and form, was engaged with the politics of its time. In it, the nature of the term working class itself is contested. This conflicted identity politics has been a long- standing feature of Irish poetry, with a whole range of writers seeking to appropriate the voice of ‘The Plain People of Ireland’ for their own political and artistic ends.3 1 W.B. -

Coffey & Chenevix Trench

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 153 Coffey & Chenevix Trench Papers (MSS 46,290 – 46,337) (Accession No. 6669) Papers relating to the Coffey and Chenevix Trench families, 1868 – 2007. Includes correspondence, diaries, notebooks, pamphlets, leaflets, writings, personal papers, photographs, and some papers relating to the Trench family. Compiled by Avice-Claire McGovern, October 2009 1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction....................................................................................................................... 4 I. Coffey Family............................................................................................................... 16 I.i. Papers of George Coffey........................................................................................... 16 I.i.1 Personal correspondence ....................................................................................... 16 I.i.1.A. Letters to Jane Coffey (née L’Estrange)....................................................... 16 I.i.1.B. Other correspondence ................................................................................... 17 I.i.2. Academia & career............................................................................................... 18 I.i.3 Politics ................................................................................................................... 22 I.i.3.A. Correspondence ........................................................................................... -

"The Given Note": Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title "The Given Note": traditional music and modern Irish poetry Author(s) Crosson, Seán Publication Date 2008 Publication Crosson, Seán. (2008). "The Given Note": Traditional Music Information and Modern Irish Poetry, by Seán Crosson. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Publisher Cambridge Scholars Publishing Link to publisher's http://www.cambridgescholars.com/the-given-note-25 version Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6060 Downloaded 2021-09-26T13:34:31Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. "The Given Note" "The Given Note": Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry By Seán Crosson Cambridge Scholars Publishing "The Given Note": Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry, by Seán Crosson This book first published 2008 by Cambridge Scholars Publishing 15 Angerton Gardens, Newcastle, NE5 2JA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2008 by Seán Crosson All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-84718-569-X, ISBN (13): 9781847185693 Do m’Athair agus mo Mháthair TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................. -

What's in an Irish Name?

What’s in an Irish Name? A Study of the Personal Naming Systems of Irish and Irish English Liam Mac Mathúna (St Patrick’s College, Dublin) 1. Introduction: The Irish Patronymic System Prior to 1600 While the history of Irish personal names displays general similarities with the fortunes of the country’s place-names, it also shows significant differences, as both first and second names are closely bound up with the ego-identity of those to whom they belong.1 This paper examines how the indigenous system of Gaelic personal names was moulded to the requirements of a foreign, English-medium administration, and how the early twentieth-century cultural revival prompted the re-establish- ment of an Irish-language nomenclature. It sets out the native Irish system of surnames, which distinguishes formally between male and female (married/ un- married) and shows how this was assimilated into the very different English sys- tem, where one surname is applied to all. A distinguishing feature of nomen- clature in Ireland today is the phenomenon of dual Irish and English language naming, with most individuals accepting that there are two versions of their na- me. The uneasy relationship between these two versions, on the fault-line of lan- guage contact, as it were, is also examined. Thus, the paper demonstrates that personal names, at once the pivots of individual and group identity, are a rich source of continuing insight into the dynamics of Irish and English language contact in Ireland. Irish personal names have a long history. Many of the earliest records of Irish are preserved on standing stones incised with the strokes and dots of ogam, a 1 See the paper given at the Celtic Englishes II Colloquium on the theme of “Toponyms across Languages: The Role of Toponymy in Ireland’s Language Shifts” (Mac Mathúna 2000).