FOR-PROFIT COLLEGES in MICHIGAN: Path Forward Or Dead End?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Undergrad Bulletin.Qxp

The Felician Sisters conduct three colleges: Felician College Lodi and Rutherford, New Jersey 07644 Villa Maria College Buffalo, New York 14225 Madonna University Livonia, Michigan 48150 MADONNA UNIVERSITY The , the first initial of Madonna, is a tribute to Mary, the patroness of Madonna University. The flame symbolizes the Holy Spirit, the source of all knowledge, and signifies the fact that liberal arts education is the aim of Madonna University whose motto is Sapientia Desursum (Wisdom from Above). The upward movement of the slanted implies continuous commitment to meeting the ever growing educational needs and assurance of standards of academic quality. The box enclosing the is symbolic of unity through ecumenism. The heavy bottom line of the box signifies the Judeo-Christian foundation of the University. (The Madonna University logo was adopted in 1980) Madonna University guarantees the right to equal education opportunity without discrimination because of race, religion, sex, age, national origin or disabilities. The crest consists of the Franciscan emblem, which is a cross and the two pierced hands of Christ and St. Francis. The Felician Sisters' emblem is the pierced Heart of Mary, with a host symbolizing the adoration of the Eucharist through the Immaculate Heart, to which the Community is dedicated. The University motto, Sapientia Desursum, is translated “Wisdom from Above”. MADONNA UNIVERSITY Undergraduate Bulletin Volume 38, 2004 - 2006 (Effective as of Term I, 2004) Madonna University 36600 Schoolcraft Livonia, Michigan 48150-1173 (734) 432-5300 (800) 852-4951 TTY (734) 432-5753 FAX (734) 432-5393 email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.madonna.edu Madonna University guarantees the right to equal educational opportunity without discrimination because of race, religion, sex, age, national origin, or disabilities. -

Bulletin 2009-2011

Madonna University Graduate Bulletin Your Success Is Our Greatest Achievement Volume 14 . 2009-2011 Madonna University Graduate Bulletin 36600 Schoolcraft Road Livonia, Michigan 48150-1176 www.madonna.edu 2009-2011 Madonna University Calendar Telephone Directory SEMESTER I — FALL 2009-2010 2010-2011 2011-2012 Faculty Conference Aug. 31 Aug. 30 Aug. 29 All phone numbers are preceded by area code 734 Final Registration Sept. 4 Sept. 3 Sept. 2 Classes Begin Sept. 8 Sept. 7 Sept. 6 Course Add Period See Tuition and Fees Section Deans and Graduate Program Directors General Information Deadline: Removal of “I” grade from Spring/Summer semester Sept. 4 Sept. 10 Sept. 9 Graduate School Office 432-5667 Central Switchboard (734) 432-5300 Filing Deadline–Application for Graduation Winter Semester, May Sept. 25 Oct. 1 Sept. 30 Dr. Edith Raleigh, Dean 432-5667 (800) 852-4951 Community Gathering Oct. 9 Oct. 8 Oct. 14 School of Business 432-5355 Orchard Lake Center (248) 683-0521 Web Registration Begins–Winter Semester Oct. 26 Oct. 25 Oct. 24 Dr. Stuart Arends, Dean 432-5366 In Person/Open Registration Begins–Winter Semester Nov. 2 Nov. 1 Oct. 31 Video Phone I.P.# 198.019.72.8 Management and Marketing Chair, Final Date, Election of S Grade Nov. 6 Nov. 5 Nov. 4 Dr. Betty Jean Hebel 432-5357 Final Filing Date/December graduation: Doctoral Capstone Experience — — Nov. 17 Management Information Systems Chair, Student Services Final Date, Withdrawal from courses Nov. 20 Nov. 19 Nov. 18 Dr. William McMillan 432-5367 **Thanksgiving Recess Nov. 26-29 Nov. 25-28 Nov. -

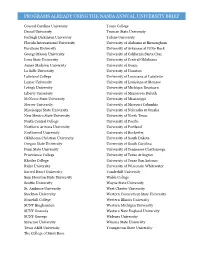

Programs Already Using the Nasba Annual University Brief

PROGRAMS ALREADY USING THE NASBA ANNUAL UNIVERSITY BRIEF Coastal Carolina University Touro College Drexel University Truman State University Farleigh Dickinson University Tulane University Florida International University University of Alabama at Birmingham Fordham University University of Arkansas at Little Rock George Mason University University of California Santa Cruz Iowa State University University of Central Oklahoma James Madison University University of Guam La Salle University University of Houston Lakeland College University of Louisiana at Lafayette Lamar University University of Louisiana at Monroe Lehigh University University of Michigan Dearborn Liberty University University of Minnesota Duluth McNeese State University University of Mississippi Mercer University University of Missouri Columbia Mississippi State University University of Nebraska at Omaha New Mexico State University University of North Texas North Central College University of Pacific Northern Arizona University University of Portland Northwood University University of Rochester Oklahoma Christian University University of South Dakota Oregon State University University of South Carolina Penn State University University of Tennessee Chattanooga Providence College University of Texas Arlington Rhodes College University of Texas San Antonio Rider University University of Wisconsin Whitewater Sacred Heart University Vanderbilt University Sam Houston State University Walsh College Seattle University Wayne State University St. Ambrose University West Chester University Stockton University Western Connecticut State University Stonehill College Western Illinois University SUNY Binghamton Western Michigan University SUNY Oneonta Western New England University SUNY Oswego Widener University Syracuse University Winona State University Texas A&M University Youngstown State University The College of Saint Rose . -

UNDERGRADUATE and GRADUATE Catalog and Student Handbook 2017—2018

UNDERGRADUATE and GRADUATE Catalog and Student Handbook 2017—2018 For more information: 1.800.686.1883 or www.cleary.edu Page i Cleary University is a member of and accredited by the Higher Learning Commission 30 North LaSalle Street Suite 2400 Chicago, IL 60602-2504 312.263.0456 http://www.ncahlc.org For information on Cleary University’s accreditation or to review copies of accreditation documents, contact: Dawn Fiser Assistant Provost, Academic Services Cleary University 3750 Cleary Drive Howell, MI 48843 The contents of this catalog are subject to revision at any time. Cleary University reserves the right to change courses, policies, programs, services, and personnel as required. Version 2.1, June 2017 For more information: 1.800.686.1883 or www.cleary.edu Page ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CLEARY UNIVERSITY ............................................................................................................................ 6 ENROLLMENT AND STUDENT PROFILE ..................................................................................................... 6 CLEARY UNIVERSITY FACULTY .................................................................................................................. 6 CLEARY UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC PROGRAMS .................................................................................. 2 OUR VALUE PROPOSITION ......................................................................................................................... 2 Graduation and Retention Rates ................................................................................................................... -

5111 Tuition Incentive Program Flyer

Tuition Incentive PROGRAM Have you ever been Medicaid eligible? What is TIP? If so, then you might be TIP eligible! If you qualified for Medicaid for at The Tuition Incentive least two years between age nine and high school graduation, you are Program encourages encouraged to contact MI Student Aid to learn more and complete your students to complete TIP application, if eligible. high school by providing college tuition assistance How Do I Complete My Application or Check My Eligibility? after graduation. There are two ways to check eligibility or complete an application: 1. Create a MiSSG Student Portal account, log in, and complete the How does TIP work? online application. 2. Call our Customer Care Center at 888-447-2687. TIP helps the student • Only eligible students may complete an application. pursue a certificate or • Eligible students must complete the application before August 31st associate degree by of their graduating year from high school. Students must graduate providing tuition and from high school before their 20th birthday. mandatory fee assistance • Beginning with the class of 2017, students who attend an Early/ at participating Michigan Middle College Program have until age 21 to graduate and institutions. complete the TIP application. Students who meet this criteria must contact us to complete the application. After earning a certificate, associate degree, or even Where is the MiSSG Student Portal? 56 transferable credits, the student can then be Go to www.michigan.gov/missg and click the Student button. eligible to receive up to What Happens After I Complete My Application? $500 per semester while pursuing a bachelor’s Only the institution you list first on your Free Application for Federal Student degree, not to exceed Aid (FAFSA) will be notified of your TIP eligibility. -

DIRECTORY (As of August 1, 2018)

DIRECTORY (As of August 1, 2018) Officers of the University Keith A. Pretty ........................................................................................................................... President and Chief Executive Officer B.S., Western Michigan University J.D., Thomas M. Cooley Law School Kristin Stehouwer ........................................................ Executive Vice President / Chief Operating Officer / Chief Academic Officer B.A., M.A., Ph.D., Northwestern University Rhonda Anderson .............................................................................................................. Vice President of Enrollment Management A.A., B.B.A., M.B.A., Northwood University Justin Marshall ................................................................................................ Vice President of Advancement and Alumni Relations A.A., B.B.A., Northwood University Timothy Nash ........................................................................................... Senior Vice President of Strategic and Corporate Alliances; A.A., B.B.A., Northwood University Robert C. NcNair Endowed Chair; M.A., Central Michigan University Director, The McNair Center for the Advancement of Ed.D., Wayne State University Free Enterprise and Entrepreneurship W. Karl Stephan .............................................................................. Vice President of Finance and Chief Financial Officer/Treasurer B.A., Yale University M.B.A., University of Chicago Rachel Valdiserri ..................................................................... -

Complete List of Participating Tuition Exchange Institutions

Complete List of Participating Tuition Exchange Institutions United Arab Emirates Massachusetts (continued) Ohio (continued) American University Sharjah - UAE Boston University - MA Mercy College of Northwest Ohio Clark University - MA - OH Greece Curry College - MA Mount St. Joseph University - American College of Greece - GR Dean College - MA OH Elms College - MA Mount Vernon Nazarene Canada Emerson College - MA University - OH King's University College at Western Emmanuel College - MA Muskingum University - OH University - CN Endicott College - MA Notre Dame College - OH Fisher College - MA Ohio Dominican University - OH Alabama Hampshire College - MA Ohio Northern University - OH Birmingham-Southern College - AL Hellenic College Holy Cross - MA Ohio Wesleyan University - OH Huntingdon College - AL Lasell College - MA Otterbein University - OH Judson College - AL Lesley University - MA Tiffin University - OH Samford University - AL Merrimack College - MA University of Dayton - OH Mount Holyoke College - MA University of Findlay - OH Alaska Mount Ida College -MA University of Mount Union - OH Alaska Pacific University - AK National Graduate School of Quality Ursuline College - OH Management - MA Walsh University - OH Arizona Newbury College - MA Wilmington College - OH Arizona Christian University - AZ Nichols College - MA Wittenberg University - OH Grand Canyon University - AZ Pine Manor College - MA Xavier University - OH Prescott College - AZ Regis College - MA Simmons College - MA Oklahoma Arkansas Smith College - MA Oklahoma City -

What Is Your

What is your POSTSECONDARY Plan? MICHIGANWhatever COLLE yourGES Postsecondary AND UNIVERSITIES Plan, Michigan offers a wide variety of college options to help you achieve it. Finlandia University (Hancock) Detroit Area Michigan Technological University • The Art Instute of Michigan (Houghton) • College for Creave Studies • Henry Ford College Bay Mills • Lawrence Technological University Community • Macomb Community College Powered by College • Madonna University Northern Michigan University • Marygrove College • Sacred Heart Major Seminary Lake Superior State University • Schoolcra College Gogebic • University of Detroit Mercy Community • University of Michigan, Dearborn College • Walsh College • Wayne County Community College District Bay de Noc • Wayne State University Community • Yeshiva Gedolah College North Central Michigan College Alpena Flint Area Community • Baker College, Flint College • Mo Community College • Keering University • University of Michigan, Flint Northwestern Michigan College Kirtland Community College Grand Rapids Area • Aquinas College West Shore • Calvin College Community Saginaw Chippewa • Compass College of Cinemac Arts College Tribal College Mid Michigan • Cornerstone University Community • Davenport University, Grand Rapids College • Grace Bible College Ferris State • Grand Rapids Community College University Northwood • Grand Valley State University Central University • Kuyper College Michigan Delta College University Saginaw Valley State Alma College University Muskegon Community College Montcalm Community -

College Night Location!

Questions to Ask! WEDNESDAY College Night October 8, 2014 Location! What are the admission requirements and what do I need to do to be accepted? How much does it cost–tuition, fees, and room/board–to attend your school? Schoolcraft College Campus Map What scholarships and/or financial aid are available? How many students are on campus and what is the average class size? Does your college offer housing? If so, COLLEGE what choices are available? Will I have a roommate? How are roommates selected? Do most students graduate in four years? night What academic resources do you offer if I need extra help? College Night Here! Representatives Is there an honors program for from more than advanced students? BOARD OF TRUSTEES 80 COLLEGES What traditions make your campus special? Brian D. Broderick ....................................... Chair & UNIVERSITIES Carol M. Strom ...................................... Vice Chair will be in attendance James G. Fausone ................................. Secretary How can I arrange a campus tour? Joan A. Gebhardt ................................... Treasurer Gretchen Alaniz ........................................ Trustee Find your What clubs, extracurricular activities, or Terry Gilligan ............................................. Trustee Eric Stempien ........................................... Trustee PERFECT COLLEGE FIT! other “extras” are available to students? Conway A. Jeffress, Ph.D., President Financial Aid information will be available! HOSTED BY SCHOOLCRAFT COLLEGE IN THE VISTATECH CENTER -

Tuition Incentive Program Fact Sheet Academic Year 2010-11

Michigan Department of Treasury 3981 (10/10) Tuition Incentive Program Fact Sheet Academic Year 2010-11 Description The Tuition Incentive Program (TIP) is an incentive program that encourages eligible students to complete high school by providing tuition assistance for the first two years of college and beyond. To meet the financial eligibility requirement, a student must have (or have had) Medicaid coverage for 24 months within a 36-consecutive-month period as identified by the Michigan Department of Human Services (DHS). TIP provides assistance in two phases. Phase I covers tuition and mandatory fee charges for eligible students enrolled in a credit-based associate degree or certificate program at a participating Michigan community college, public university, degree-granting independent college, federal tribally-controlled college, or Focus: HOPE. Phase II provides a maximum of $2,000 total tuition assistance for credits earned in a four-year program at an in-state, degree-granting college or university. Award parameters are subject to legislative changes. Application Students are identified by DHS as having met the Medicaid eligibility requirement. Students may be identified as TIP eligible as early as sixth grade, using the 36-month period immediately preceding enrollment in the sixth grade. Medicaid eligibility prior to that 36-month period is not counted. After being identified, the Office of Scholarships and Grants (OSG) will send the student an acceptance form. The student must then complete the acceptance form and return it to OSG before graduation from high school or GED completion1 and before their 20th birthday to activate financial eligibility for the program. -

UNDERGRADUATE and GRADUATE Catalog and Student Handbook 2011—2012

UNDERGRADUATE and GRADUATE Catalog and Student Handbook 2011—2012 For more information: 1.800.686.1883 or www.cleary.edu Page i Page ii For more information: 1.800.686.1883 or www.cleary.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS CLEARY UNIVERSITY............................................................................................................................................. 1 ENROLLMENT AND STUDENT PROFILE ......................................................................................................... 1 CLEARY UNIVERSITY FACULTY ...................................................................................................................... 1 LEARNING ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................................................................... 1 CLEARY UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC PROGRAMS ................................................................................................... 2 Program Features ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Institutional Learning Outcomes .......................................................................................................................... 2 ACADEMIC PROGRAMS ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Traditional Program ............................................................................................................................................ -

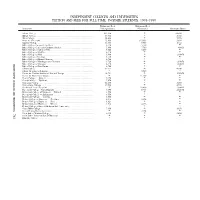

Independent Colleges and Universities Tuition and Fees for Full-Time, In-State Students, 1998-1999

INDEPENDENT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES TUITION AND FEES FOR FULL-TIME, IN-STATE STUDENTS, 1998-1999 Tuition and Fees Tuition and Fees Institution (Undergraduate) (Graduate) Room and Board Adrian College . $13,150 **0 $4,630 Albion College . 17,712 **0 5,072 Alma College . 14,424 **0 5,250 Andrews University . 13,098 $13,835 3,630 Aquinas College . 13,168 5,580 4,432 Baker College Corporate Services . 6,720 5,160 **0 Baker College Center for Graduate Studies . 5,040 7,700 600(R) Baker College of Auburn Hills . 5,040 5,600 **0 Baker College of Cadillac . 6,720 **0 **0 Baker College of Flint . 5,060 **0 1,800(R) Baker College of Jackson . 6,720 **0 **0 Baker College of Mount Clemens . 6,720 **0 **0 Baker College of Muskegon and Fremont . 6,720 **0 1,800(R) INDEPENDENT COLLEGES ANDUNIVERSITIES Baker College of Owosso . 6,720 **0 1,800(R) Baker College of Port Huron . 6,720 **0 **0 Calvin College . 12,915 **0 4,500 Calvin Theological Seminary . **0 5,520 **0 Center for Creative Studies of Arts and Design . 14,721 **0 3,050(R) Center for Humanistic Studies . **0 11,700 **0 Cleary College — Howell . 7,470 **0 **0 Cleary College — Ypsilanti . 7,470 **0 **0 Concordia College . 12,200 **0 5,250 Cornerstone College . 10,026 **0 4,592 Cranbrook Academy of Art . **0 14,400 2,800(R) Davenport College (Grand Rapids) . 7,695 5,736 2,325(R) Davenport College of Business — Holland . 8,550 **0 **0 Davenport College — Kalamazoo .