The Case of Estonian Chefs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Starter Main Course Dessert Healthy-Drink Healthy-Snack Menu

Menu Estonia Starter Salad Main Course Dessert Healthy-Drink Kama Healthy-Snack BLACK BREAD WITH BALTIC SPRATS Healthy Recipes Salad Ingredients Salad Chopped tomatoes Ingredients Dressing Celery Olive oil Spring onions Balsamic vinegar or Sliced cucumbers fresh-squeezed lemo- Sliced radishes ne juice Small amount of cheese Fresh spices Tuna Cauliflower Broccoli Carrots Preparation Add chopped tomatoes, celery, spring onions, sliced cucumbers and sliced radishes. Add a small amount of cheese. Cheese is high in calories and fat, so use sparingly. Add tuna. Then combine a variety of vegetables like cauliflower, broccoli, carrots. Toss the vegetable combination in- to the salad. Top off your salad by sprinkling on a homemade dressing (olive oil is very good for you when not heat- ed), balsamic vinegar or fresh-squeezed lemon juice. For a different taste, throw in some fresh spices like dill, oregano, basil or garlic. Page 2 ESTLAND Healthy Body Healthy Mind Main Course Ingredients sauer kraut potatoes, peeled beef roast different spices (pepper, mustard, etc.) salt water, 1 cup mustard, for serving Preparation Preheat oven to 180 °C. Place the beef on a roasting pan, rub with spices and salt. Add the water and put it into the oven for 120-160 mins. While the beef is cooking, boil the potatoes in a salted water and heat up the sauerkraut. When ready, set the table and call everyone in for the meal! The meat will taste best with a touch of mustard. You can drink whatever beverage you prefer. Page 3 Healthy Body Healthy Mind ESTLAND Dessert Ingredients 100 gr butter 1 dl dark Muscovado sugar 3 spoonful kama flour 3 dl oatmeal (cereals) 1 egg 100 gr white chocolate Preparation Mix the sugar, egg, cereals and kama flour with butter (butter has to be in room temperature). -

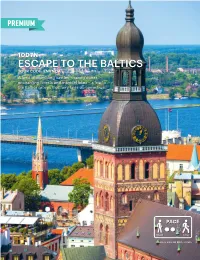

Escape to the Baltics

PREMIUM 10D7N ESCAPE TO THE BALTICS TOUR CODE: ENVNOA A land of crumbling castles, soaring dunes, enchanting forests and magical lakes – a trip to the Baltics proves that fairy tales do come true. 123RF AERIAL VIEW OF RIGA, LATVIA PHOTO: 34 Northern Europe | EU Holidays Helsinki HIGHLIGHTS Tallinn LITHUANIA 2 Estonia VILNIUS • Vilnius Cathedral Basilica Flight path Parnu • Pilies Street Traverse by coach • St. Anne’s, Bernardine’s and St. Michael’s Traverse by cruise Churches Featured destinations 2 • Orthodox Church Overnight stays 1 2 3 Riga Latvia • Gate of Dawn • Vilnius University Lithuania LATVIA 2 RIGA • Dome Cathedral (entrance included) Vilnius • St. Peter’s Tower • Old Guild Houses Poland • Riga Castle 1 • Swedish Gate Warsaw ESTONIA TALLINN • Old Town tour • Gothic Town Hall • Toompea • Alexander Nevski Cathedral DAY 1 among bogs, stumble upon old Soviet ruins HOME → HELSINKI like an abandoned submarine station and see DELICACIES Meals on Board exquisite centuries-old manor houses. Assemble at the airport and take-off to the Meal Plan city of Helsinki, Finland’s southern capital, DAY 4 7 Breakfasts, 3 Lunches, 4 Dinners sits on a peninsula in the Gulf of Finland. TALLINN → PÄRNU → RIGA Breakfast, Latvian Dinner Specialities DAY 2 Join a short sightseeing tour in Pärnu, the Estonian Cuisine HELSINKI TALINN Estonian resort town. The summer capital, Lativan Cuisine → Meals on Board, Estonian Dinner Pärnu, is a town of parks, alleys, beaches, Lithuanian Cuisine Upon arrival, free at leisure till time to board a warm shallow waters and health spas ferry to Tallinn, Estonia’s capital on the Baltic offering various curative treatments including Sea, is the country’s cultural hub. -

Download for the Reader

Folklore Electronic Journal of Folklore http://www.folklore.ee/folklore Printed version Vol. 71 2018 Folk Belief and Media Group of the Estonian Literary Museum Estonian Institute of Folklore Folklore Electronic Journal of Folklore Vol. 71 Edited by Mare Kõiva & Andres Kuperjanov Guest editor: Liisi Laineste ELM Scholarly Press Tartu 2018 Editor in chief Mare Kõiva Co-editor Andres Kuperjanov Guest editor Liisi Laineste Copy editor Tiina Mällo News and reviews Piret Voolaid Design Andres Kuperjanov Layout Diana Kahre Editorial board 2015–2020: Dan Ben-Amos (University of Pennsylvania, USA), Larisa Fialkova (University of Haifa, Israel), Diane Goldstein (Indiana University, USA), Terry Gunnell (University of Iceland), Jawaharlal Handoo (University of Mysore, India), Frank Korom (Boston University, USA), Jurij Fikfak (Institute of Slovenian Ethnology), Ülo Valk (University of Tartu, Estonia), Wolfgang Mieder (University of Vermont, USA), Irina Sedakova (Russian Academy of Sciences). The journal is supported by the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (IUT 22-5), the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund (Centre of Excellence in Estonian Studies), the state programme project EKKM14-344, and the Estonian Literary Museum. Indexed in EBSCO Publishing Humanities International Complete, Thomson Reuters Arts & Humanities Citation Index, MLA International Bibliography, Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory, Internationale Volkskundliche Bibliographie / International Folklore Bibliography / Bibliographie Internationale d’Ethnologie, -

Best of British Best

Foo d and Tr a vel June 2011 Issue No 137 Estonia, Suffolk, Mongolia, Osijek, Mainz, Toulouse, Seaside Rentals vel June 2011 Issue No 137 Estonia, Suffolk, Mongolia, Osijek, Mainz, Toulouse, , Food Festivals, Raymond Blanc, Broad Beans WORLD FOOD from China, Estonia and Morocco Raymond Blanc Horseback adventures in shares his kitchen secrets Mongolia Why it's worth indulging in Taste the experience – taste Taste CITY BREAKS California wine France, Germany and Croatia £3.95 BEST OF BRITISH FOOD FESTIVALS GOURMET TRAVEL SEASIDE RENTALS SAVING HONEY JUNE 2011 001_Food cover repro OPTION.indd 1 15/4/11 15:35:36 SEAN - PLEASE PLACE NEW COVERS THX 26 On the cover 28 Estonia 38 Mongolia WO RL D FOOD from China, Estonia and Morocco Horseback adventures in M o n g o l i a 47 Raymond Blanc 65 Best of British s s Raymond Blanc shares his kitchen secrets WO RL D FOOD from China, Estonia a n d Mo r o c c o Raymond Blanc 74 Seaside rentals Horseback adventures in shares his kitchen secrets Why it's worth indulging in Mo n g o l i a Why it's worth indulging in California w i n e C I T Y BR EAKS California wine France, Germany and Croatia C I T Y BR EAKS £3.95 £3.95 France, Germany and Croatia 93 City breaks BEST OF BRITISH BEST OF BRITISH F O O D FE S T I V A L S GOU RM E T T RAVEL SE A S I D E RE N T A L S SAVIN G H O N E Y F O O D FESTIVALS GOU RM E T T RAVEL SE A S I D E RENTALS SAVIN G H O N E Y JUNE 2011 JUNE 2011 113 California wine 66 t t Regulars Features 7 Arrivals 28 Baltic flavours 00 The latest food, drink and travel Francis Pearce samples -

To View Online Click Here

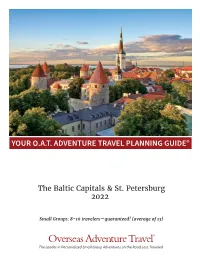

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® The Baltic Capitals & St. Petersburg 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Enhanced! The Baltic Capitals & St. Petersburg itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: What I love about the little town of Harmi, Estonia, is that it has a lot of heart. Its residents came together to save their local school, and now it’s a thriving hub for community events. Harmi is a new partner of our Grand Circle Foundation, and you’ll live a Day in the Life here, visiting the school and a family farm, and sharing a farm-to-table lunch with our hosts. I love the outdoors and I love art, so my walk in the woods with O.A.T. Trip Experience Leader Inese turned into something extraordinary when she led me along the path called the “Witches Hill” in Lithuania. It’s populated by 80 wooden sculptures of witches, faeries, and spirits that derive from old pagan beliefs. You’ll go there, too (and I bet you’ll be as surprised as I was to learn how prevalent those pagan practices still are.) I was also surprised—and saddened—to learn how terribly the Baltic people were persecuted during the Soviet era. -

Tallinn Travel Guide

TALLINN TRAVEL GUIDE FIREFLIES TRAVEL GUIDES TALLINN Steeped in Medieval charm, yet always on the cutting- edge of modernity, Tallinn offers today’s travelers plenty to see. The city is big enough and interesting enough to explore for days, but also small and compact enough to give you the full Tallinn experience in just a few hours. DESTINATION: TALLINN 1 TALLINN TRAVEL GUIDE Kids of all ages, from toddlers to teens, will love ACTIVITIES making a splash in Tallinn’s largest indoor water park, conveniently located at the edge of Old Town. Visitors can get their thrills on the three water slides, work out on the full length pool or have a quieter time in the bubble-baths, saunas and kids’ pool. The water park also has a stylish gym offering various training classes including water aerobics. Aia 18 +372 649 3370 www.kalevspa.ee Mon-Fri 6.45-21.30, Sat-Sun 8.00-21.30 If your idea of the perfect getaway involves whacking a ball with a racquet, taking a few laps at MÄNNIKU SAFARI CENTRE high speed or battling your friends with lasers, The Safari Centre lets groups explore the wilds of then Tallinn is definitely the place to be. Estonia on all-terrain quad bikes. Groups of four to 14 people can go on guided trekking adventures There are sorts of places to get your pulse rate up, that last anywhere from a few hours to an entire from health and tennis clubs to skating rinks to weekend. Trips of up to 10 days are even available. -

INSTRUCTIONS for FOCUS TOPIC of CULTURAL HOLIDAY Estonian Culture Is Extensive and Deep, and Has Through the Ages Reached High Levels During Its Peak Moments

“Introduce Estonia” sub-strategy for tourism INSTRUCTIONS FOR FOCUS TOPIC OF CULTURAL HOLIDAY Estonian culture is extensive and deep, and has through the ages reached high levels during its peak moments. It is impossible to visit Estonia without encountering the local culture. Many things that seem regular and daily to us might be very interesting and exciting cultural phenomena for bystanders. It is our task to find these and make them work for all of us. In order to illustrate positive messages we should find vivid and surprising facts and details, using the principle of contrast to accentuate them. For example, contradictions could be the medieval buildings of Tallinn Old Town offering modern culinary and entertainment culture and wireless Internet, or high culture events taking place basically in the middle of nowhere (Leigo, Nargen Opera, Viinistu). This is a fruitful approach as contradiction and contrast is one of the pervading and essential elements of the so called Estonian thing. On one hand our habits and culture are individualistic, people needing a lot of personal space (e.g. low density areas of farms), on the other hand gaining independence through massive events (Song Festivals, The Singing Revolution, The Baltic Way). As Estonian culture is such a broad concept, the suitable symbols for generating a message are divided into four focus topics: A ARCHITECTURE B TRADITIONAL CULTURE C MODERN CULTURE D CUISINE Depending on the target audience you can choose the most suitable of these or combine several topics. Arguments: Culture can be FOUND both in cities and rural areas. It is impossible to travel in Estonia without encountering the local culture. -

Estonian Cuisine

ESTONIAN 200 g boiled carrots CUISINE 2–3 boiled eggs 200 g roasted pork or boiled meat 1 medium salted herring Beetroot salad 700 g boiled beetroot Dressing: 5 dl 20% sour cream, salt, 0.5 teaspoonfuls mustard, 1–2 pickled cucumbers a pinch of sugar From the heyday of the Republic of Estonia 400 g boiled potatoes in the 1930s until the late 1950s, no decent party in the country was held without beetroot salad. This fashionable dish was gradually replaced Cut everything (except eggs) into by potato salad that is much easier to prepare. small cubes. For the dressing, mix Besides, the latter contains no herring, a fish not soured cream, mustard, salt and to everyone’s liking. It is worthwhile recalling sugar. Add the cubes, leave for an hour this nearly forgotten dish, as correctly prepared or two. Cover the salad with crushed egg whites and yolks. beetroot salad is quite exceptional and resem- 2 apples bles no other mixed salad today. ESTONIAN CUISINE Chicken-dumpling soup 1 whole chicken water 1 onion – unpeeled salt 10 grains of pepper 5 potatoes 3 carrots freshly chopped herbs (parsley, dill, chive) butter for frying Dumplings: 100 ml broth 1 egg 0.5 teaspoons salt 100 g 20% sour cream 2 dl flour Put the chicken into cold water, bring to a boil. Remove froth. Add salt, pepper and unpeeled onion. Allow to simmer for an hour or an hour and a half, until the chicken is soft. Remove the chicken and the onion. Scoop out a ladle of fatty broth for dump- lings from the surface. -

Tallinn Guide Tallinn Guide Money

TALLINN GUIDE TALLINN GUIDE MONEY The Estonian currency is the euro = 100 cents. 4* hotel (average price/night) – €100 Essential Information Car-hire (medium-sized car/day) – €120 Money 3 The majority of larger restaurants, hotels and shops accept credit cards, but always have some Tipping Communication 4 Tallinn, the capital of Estonia and a seaport cash on you, especially for taxis and bus tickets. Tipping in Estonia is voluntary and tips are never with nearly 420,000 inhabitants, is a vibrant Smaller shops, some petrol stations and B&Bs included in the bill. You are not obliged to leave Holidays 5 city mixing old and new. Its charming histor- may not accept card payments, so always check a tip, but a common practise is to leave 10% in in advance. ATMs are scattered around the city Transportation 6 ical center is listed as a UNESCO World Her- restaurants if the service was satisfactory. itage Site, but Tallinn is also often referred to and it should never be a problem finding one. You Food 8 as the Silicon Valley of the Baltic Sea, rank- can exchange money at any bank or exchange of- ing as one of the top 10 digital cities in the fice. Try to avoid the exchange booths in the Old Events During The Year 9 world. On one hand, it is the birthplace of Town, the rates are not very good there. You can Skype and home to a big Ericsson production also just withdraw money from the ATM if you 10 Things to do plant for Europe; on the other hand, it is home want to save yourself trouble. -

Mining Cross-Cultural Relations from Wikipedia - a Study of 31 European Food Cultures

Mining cross-cultural relations from Wikipedia - A study of 31 European food cultures Paul Laufer Claudia Wagner Graz University of Technology GESIS & U. of Koblenz Graz, Austria Cologne, Germany [email protected] [email protected] Fabian Flöck Markus Strohmaier GESIS GESIS & U. of Koblenz Cologne, Germany Cologne, Germany fabian.fl[email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT the editor community of the Romanian-language Wikipedia For many people, Wikipedia represents one of the primary could either have a deviant mental picture of the French sources of knowledge about foreign cultures. Yet, differ- cuisine { or it might estimate the priorities of Romanian- ent Wikipedia language editions offer different descriptions speaking readers to rather be on meat-based French deli- of cultural practices. Unveiling diverging representations of catessen than on wine and baking goods. Further, the gen- cultures provides an important insight, since they may foster eral interest of the Romanian-speaking readers in the French the formation of cross-cultural stereotypes, misunderstand- cuisine (for example measured by the number of views of the ings and potentially even conflict. In this work, we explore article about French cuisine in the Romanian language edi- to what extent the descriptions of cultural practices in var- tion) might serve to potentially displease any Francophile, ious European language editions of Wikipedia differ on the since the Romanian speaking community might show no- example of culinary practices and propose an approach to tably less interest in the French kitchen than in the Russian mine cultural relations between different language commu- or Hungarian one. This hypothetical scenario serves as an nities trough their description of and interest in their own example for numerous similar real-world cases (which can- and other communities' food culture. -

Deeper Connection with Points That Show How Estonian Cuisine Enables Travellers to Make the Most of Their the Restaurants, Recipes and Ingredients They Discover

Visit Estonia Experiences with Food Strategy and Story Introduction We talk about Estonia’s food-based travel experiences to an audience of Flavour Seekers. For them, dining is as much about understanding the ingredients, as it is about enjoying the meal, meaning foraging for mushrooms is as life affirming as five-star dining. Brand Essence Our Brand Essence distils our strategy into a few short words, capturing Estonia’s spellbinding ability to flex its space and time, so it’s tailored to the traveller. It’s about time Experience Positioning Estonia is the insatiable choice for the Flavour Seeker. Our Experience Positioning is a brief description of the overall experience offered It’s for those wanting to experience food at their own pace to the Flavour Seeker. It highlights proof and those who want to experience a deeper connection with points that show how Estonian cuisine enables travellers to make the most of their the restaurants, recipes and ingredients they discover. precious time when travelling. Because in Estonia, no matter your schedule, you’ll have all the time in the world; Centuries of influence slowly simmer together. Foraging for mushrooms means getting lost in the moment. Fine dining can last a day, and fast food comes as fast as it grows. Thanks to our compact size and effortless accessibility,Estonia tailors its time to the traveller, meaning you can better connect to our food – and your own. Experience Promise Through our compact size and effortless accessibility, Our Experience Promise outlines our commitment to our audience and our we commit to enabling Flavour Seekers to make the ambition for their experience when most of their time when discovering our food. -

Cima Xviii 2017

Traditions and Change – Sustainable Futures PROCEEDINGS http://cima2017.publicon.ee 18th triennial Congress of International Association of Agricultural Museums (AIMA) Hosted by Estonian Agricultural Museum Co-financed by Estonian Ministry of Rural Affairs Secretariat Publicon PCO Ltd Print version sponsored by Proceedings compiled by Merli Sild Scientific Committee: Debra Reid, Kerry-Leigh Burchill, Oliver Douglas, Merli Sild, Rando Värnik Proofreading by Piret Hion Design and layout by Marat Viires ISBN 978-9949-9933-2-1 ISBN 978-9949-9933-3-8 (pdf) Downloadable at www.agriculturalmuseums.org www.maaelumuuseumid.ee Printed by Vali Press Ltd Introduction to CIMA XVIII The purpose of AIMA is to educate the public about the significance of agriculture to human society, to explain the many ways that agriculture has evolved through time, and facilitate dialogue between museums across the globe about agricultural topics and discoveries. Today, museums face a momentous task of keeping up with changes while keeping alive the invaluable past. At AIMA’s triennial congress CIMA XVIII we focussed on how traditions and rural heritage can be used to create changes for sustainable futures. Agricultural museums take many forms – they operate as research institutions, as places of civic dialogue, and as repositories of tangible and intangible cultural heritage. Their collections grew during periods when rapid outmigration from rural and farm settings prompted public memorialisation of rural and farm expe- riences. The following questions were addressed: 1. How can rural heritage be used to ensure global food safety? 2. Should modern museums expand missions to incorporate the current social reactions to agricultural controversies (such as GMOs, government regulation, and chemical applications and environmental effects)? 3.