Gascoigne Et Al.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'A Mind to Copy': Inspired by Meissen

‘A Mind to Copy’: Inspired by Meissen Anton Gabszewicz Independent Ceramic Historian, London Figure 1. Sir Charles Hanbury Williams by John Giles Eccardt. 1746 (National Portrait Gallery, London.) 20 he association between Nicholas Sprimont, part owner of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, Sir Everard Fawkener, private sec- retary to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the second son of King George II, and Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, diplomat and Tsometime British Envoy to the Saxon Court at Dresden was one that had far-reaching effects on the development and history of the ceramic industry in England. The well-known and oft cited letter of 9th June 1751 from Han- bury Williams (fig. 1) to his friend Henry Fox at Holland House, Kensington, where his china was stored, sets the scene. Fawkener had asked Hanbury Williams ‘…to send over models for different Pieces from hence, in order to furnish the Undertakers with good designs... But I thought it better and cheaper for the manufacturers to give them leave to take away any of my china from Holland House, and to copy what they like.’ Thus allowing Fawkener ‘… and anybody He brings with him, to see my China & to take away such pieces as they have a mind to Copy.’ The result of this exchange of correspondence and Hanbury Williams’ generous offer led to an almost instant influx of Meissen designs at Chelsea, a tremendous impetus to the nascent porcelain industry that was to influ- ence the course of events across the industry in England. Just in taking a ca- sual look through the products of most English porcelain factories during Figure 2. -

Non-Invasive On-Site Raman Study of Blue

Non-invasive on-site Raman study of blue-decorated early soft-paste porcelain: The use of arsenic-rich (European) cobalt ores – Comparison with huafalang Chinese porcelains Philippe Colomban, Ting-An Lu, Véronique Milande To cite this version: Philippe Colomban, Ting-An Lu, Véronique Milande. Non-invasive on-site Raman study of blue-decorated early soft-paste porcelain: The use of arsenic-rich (European) cobalt ores – Comparison with huafalang Chinese porcelains. Ceramics International, Elsevier, 2018, 10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.02.105. hal-01723496 HAL Id: hal-01723496 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01723496 Submitted on 5 Mar 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Non-Invasive on-site Raman study of blue-decorated early soft-paste porcelain: the use of Arsenic-rich (European) cobalt ores – Comparison with huafalang Chinese porcelains Philippe Colomban, 1 Ting-An Lu1, Véronique Milande2 1 Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Univ. Paris 06, MONARIS UMR8233, CNRS, 4 Place Jussieu, 75005 Paris, France 2 Département du Patrimoine et des Collections de la Cité de la Céramique, 92310 Sèvres, France corresponding author : [email protected] Tel+33144272785 ; fax +33144273021 Abstract Both European and Asian historical records report that Jesuits were at the origin of enamelling technology transfers from France (and Italy) to Asia during the 17th century. -

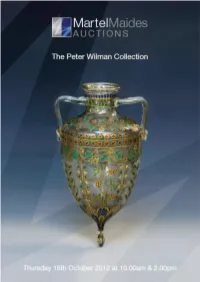

The Wilman Collection

The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Lot 1 Lot 4 1. A Meissen Ornithological part dessert service 4. A Derby botanical plate late 19th / early 20th century, comprising twenty plates c.1790, painted with a central flower specimen within with slightly lobed, ozier moulded rims and three a shaped border and a gilt line rim, painted blue marks square shallow serving dishes with serpentine rims and and inscribed Large Flowerd St. John's Wort, Derby rounded incuse corners, each decorated with a garden mark 141, 8½in. (22cm.) diameter. or exotic bird on a branch, the rims within.ects gilt £150-180 edges, together with a pair of large square bowls, the interiors decorated within.ects and the four sides with 5. Two late 18th century English tea bowls a study of a bird, with underglaze blue crossed swords probably Caughley, c.1780, together with a matching and Pressnumern, the plates 8¼in. (21cm.) diameter, slop bowl, with floral and foliate decoration in the dishes 6½in. (16.5cm.) square and the bowls 10in. underglaze blue, overglaze iron red and gilt, the rims (25cm.) square. (25) with lobed blue rings, gilt lines and iron red pendant £1,000-1,500 arrow decoration, the tea bowls 33/8in. diameter, the slop bowl 2¼in. high. (3) £30-40 Lot 2 2. A set of four English cabinet plates late 19th century, painted centrally with exotic birds in Lot 6 landscapes, within a richly gilded foliate border 6. -

Philippa H Deeley Ltd Catalogue 17 Oct 2015

Philippa H Deeley Ltd Catalogue 17 Oct 2015 1 A Pinxton porcelain teapot decorated in gilt with yellow cartouches with gilt decoration and hand hand painted landscapes of castle ruins within a painted botanical studies of pink roses, numbered square border, unmarked, pattern number 300, 3824 in gilt, and three other porcelain teacups and illustrated in Michael Bertould and Philip Miller's saucers from the same factory; Etruscan shape 'An Anthology of British Teapots', page 184, plate with serpent handle, hand painted with pink roses 1102, 17.5cm high x 26cm across - Part of a and gilt decoration, the saucer numbered 3785 in private owner collection £80.00 - £120.00 gilt, old English shape, decorated in cobalt blue 2 A Pinxton porcelain teacup and saucer, each with hand painted panels depicting birds with floral decorated with floral sprigs and hand painted gilt decoration and borders, numbered 4037 in gilt landscapes with in ornate gilt surround, unmarked, and second bell shape, decorated with a cobalt pattern no. 221, teacup 6cm high, saucer 14.7cm blue ground, gilt detail and hand painted diameter - Part of a private owner collection £30.00 landscape panels - Part of a private owner - £40.00 collection £20.00 - £30.00 3 A porcelain teapot and cream jug, possibly by 8A Three volumes by Michael Berthoud FRICS FSVA: Ridgway, with ornate gilding, cobalt blue body and 'H & R Daniel 1822-1846', 'A Copendium of British cartouches containing hand painted floral sparys, Teacups' and 'An Anthology of British Teapots' co 26cm long, 15cm high - -

Oriental & European Ceramics & Glass

THIRD DAY’S SALE WEDNESDAY 24th JANUARY 2018 ORIENTAL & EUROPEAN CERAMICS & GLASS Commencing at 10.00am Oriental and European Ceramics and Glass will be on view on: Friday 19th January 9.00am to 5.15pm Saturday 20th January 9.00am to 1.00pm Sunday 21st January 2.00pm to 4.00pm Monday 22nd January 9.00am to 5.15pm Tuesday 23rd January 9.00am to 5.15pm Limited viewing on sale day Measurements are approximate guidelines only unless stated to the contrary Enquiries: Andrew Thomas Enquiries: Nic Saintey Tel: 01392 413100 Tel: 01392 413100 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 661 662 A large presentation wine glass and a pair of wine glasses Two late 18th century English wine glasses, one similar the former with bell shaped bowl engraved with the arms of and an early 19th century barrel-shaped tumbler the first Weston, set on a hollow knopped stem and domed fold over two with plain bowls and faceted stems, 13.5 cm; the third foot, 27 cm high, the pair each with rounded funnel shaped engraved with floral sprays and on faceted stem, 14 cm; the bowl engraved with an eagle’s head set on a double knopped tumbler engraved with urns, paterae and swags with the stem and conical foot, 23 cm high. initials ‘GS’,11 cm (4). *£200 - 250 *£120 - 180 663 A George Bacchus close pack glass paperweight set with various multi coloured canes and four Victoria Head silhouettes, circa 1850, 8 cm diameter, [top polished]. *£300 - 500 664 665 A Loetz Phanomen glass vase of A Moser amber crackled glass vase of twelve lobed form with waisted neck shaped globular form, enamelled with and flared rim, decorated overall with a a crab, a lobster and fish swimming trailed and combed wave design, circa amongst seaweed and seagrass, circa 1900-05, unmarked, 19 cm high. -

Oriental & European Ceramics & Glass

SECOND DAY’S SALE WEDNESDAY 17th APRIL 2019 ORIENTAL & EUROPEAN CERAMICS & GLASS Commencing at 10.00am Oriental and European Ceramics and Glass will be on view on: Friday 12th April 9.00am to 5.15pm Saturday 13th April 9.00am to 1.00pm Sunday 14th April 2.00pm to 4.00pm Monday 15th April 9.00am to 5.15pm Tuesday 16th April 9.00am to 5.15pm Limited viewing on sale day Measurements are approximate guidelines only unless stated to the contrary Enquiries: Andrew Thomas Enquiries: Nic Saintey Tel: 01392 413100 Tel: 01392 413100 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 521 522 A group of four English wine glasses Two English wine glasses of Jacobite comprising a pair with bell-shaped interest each with rounded funnel bowls with basal tiers extending into shaped bowls, engraved with a bloom an air twist stem with vermiform collar and an insect verso, set on straight on a conical foot, circa 1750, 17 cm [rim double series opaque twist stems on chip], together with a pair of double conical foot, circa 1750-60, 14.5 cm and series opaque twist champagne flutes, 15 cm [chips to both foot rims] 20.5 cm [chip to foot rim] *£200 - 300 *£100 - 200 523 A Cork, probably Waterloo Glass Co., mould blown decanter of mallet shaped form with double feathered triple neck rings and basal comb flutes and flattened grid stopper, embossed marks to base, circa 1800, 27 cm high. *£200 - 300 524 A group of seven Bristol blue glass decanters and stoppers each of mallet shaped form with lozenge stoppers decorated with gilt labels, chains and embellishments, three for Rum, two Brandy and one each of Shrub and Hollands, 22 - 25 cm high. -

Antiques & Collectables

Antiques & Collectables Thursday 26 July 2012 10:30 British Bespoke Auctions The Old Boys School Gretton Road Winchcombe GL54 5EE British Bespoke Auctions (Antiques & Collectables) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Lot: 10 TWO OBLONG STONE PLANTERS - APPROX. 66cm LONG, A GENT'S VINTAGE SILK COURT HAT BY EDE & 23cm WIDE (2) RAVENSCROFT, THE HAT HAVING MARCASITE STEEL Estimate: £20.00 - £30.00 TRIMMINGS TOGETHER WITH A CHRISTYS LONDON ASCOT HAT Estimate: £15.00 - £20.00 Lot: 2 A WEATHERED STONE GARDEN BIRD BATH IN THE FORM OF A GIRL SITTING WHILE HOLDING A SHELL, APPROX. Lot: 11 100cm HIGH A MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTION OF THREE OPERA Estimate: £60.00 - £80.00 GLASSES IN THEIR ORIGINAL CASES, ONE BY W HEATH AND CO, PLYMOUTH. (3) Estimate: £15.00 - £20.00 Lot: 3 A LARGE OLIVE GREEN FREE-STANDING GARDEN TRELLIS, APPROX. 62cm LONG X 180cm HIGH Lot: 12 Estimate: £20.00 - £30.00 THREE ASSORTED ITEMS COMPRISING A PAIR OF LEATHER SLEEVED WADE BINOCULARS TOGETHER WITH A VICTORIAN BRASS TOPPED GLASS INKWELL AND A Lot: 4 GLASS PAPER WEIGHT DEPICTING A CASTLE (3) A VINTAGE WOOD AND CANVAS STEAMER TRUNK Estimate: £15.00 - £20.00 LABELLED BRANTED FAXITE FIB TOGETHER WITH A VINTAGE LEATHER SUITCASE AND A TRAVELLING HAT BOX INITIALLED C M H (3) Lot: 13 Estimate: £20.00 - £30.00 A CHINESE FUKIEN INTRICATE COURT PICTURE DEPICTING A PAGODA AND CRANES TOGETHER WITH AN ANTIQUE CHINESE BLACK LACQUER BOX DEPICTING Lot: 5 FLOWERS (2) A VINTAGE ELECTROLUX VACUUM CLEANER IN ORIGINAL Estimate: £15.00 - £20.00 WOODEN CASE Estimate: £15.00 - £20.00 Lot: 14 A CARVED QUARTZ STONE Lot: 6 Estimate: £15.00 - £20.00 A HARDY SPLIT CANE FOUR PIECE TROUT ROD, 'THE FAIRY ROD' PLAKONA REGD. -

Albert Amor Ltd

ALBERT AMOR LTD. RECENT ACQUISITIONS AUTUMN 2019 37 BURY STREET, ST JAMES’S, LONDON SW1Y 6AU Opening Times Monday to Friday 10.00am - 5.30pm Saturday and Sunday by appointment Telephone: 0207 930 2444 www.ALBERTAMOR.co.uk Foreword I am delighted this autumn to present a catalogue of our recent acquisitions, the largest such catalogue we have issued for some time, and with a great variety of 18th and 19th century pieces. Amongst these, there are many items with an illustrious provenance, and many that have been widely illustrated over the years. We were fortunate to acquire a fine group of early Derby and important Rockingham from the collection of the late Dennis Rice, many pieces illustrated and discussed in his various books, including the rare mug, number 39, which he had acquired from us, and the unrecorded Rockingham horse, number 85. From a distinguished American collection we offer a superb pair of Bow models of Kestrels, a rare Chelsea group and two Chelsea figures, formerly in the celebrated collection of Irwin Untermyer at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The rare early Chelsea beaker, number 7, was in the T D Barclay Collection, and the very unusual Chelsea vase, number 16, was formerly in the John Hewett Collection, and exhibited here in 1997. A great element of the history of Albert Amor Limited is our reputation for helping to form collections, and then in later years be called upon to help curate and disperse those collections again. For twenty five years I have been fortunate to work with Rt. -

Rough Notes on Pottery

0- A Lasting Pleasure * one of JOHN MADD0CK& SONS, ud. j & Royal Vitreous & Dinner, Tea or Toilet Sets They cost just a little more than the ordinary kinds, but all better things do Beautiful Shapes * «fe Tasty, Modern, Up-to-date Decorations Novel, Attractive Colors For sale by all First-Class Dealers in Pottery who will substantiate every claim we have advanced & ^ Look at this Stamp The Potters' Art can produce Thej' are made by JOHN MADDOCK & SONS, Ltd., BURSLEM, ENGLAND. CAUTION. Be sure in buying that the name Maddock and England are BOTH on the stamp as our mark has been extensively copied. For Hotels, Boarding-houses, etc., we make goods of special strength for their require- ments. Inquire about Maddock' s goods at your nearest China Store. — CONTENTS. Page. BY WAY OF PREFACE 6 THE ANTIQUITY OF POTTERY 7 AN ICONOCLAST 8 EARLY ENGLISH POTTERY g-J2 Dwight Stoneware—The Elers— Salt Glaze John Astbury's Discovery of Flint- Ralph Shaw—Whieldon—Cookworthy— The New Hall China- Liverpool— Leeds- Rockingham Ware. JOSIAH WEDGWOOD AND HIS SUCCESSORS 13-17 MINTONS 18-22 SPODE—COPELAND—PARIAN 23-25 DAVENPORTS 25 CAULDON (BROWN-WESTHEAD MOORE & CO.) 25 AMERICAN HISTORICAL EARTHENWARE 27-31 FOR THE AMERICAN MARKET 32-33 T. & R. Boote — The Old Hall Earthenware Co.— Geo. Jones & Sons—Johnson Bros.—J. & G. Meakin—Furnivals— Burton Factories - Burmantofts Luca della Robbia Pottery. JOHN MADDOCK & SONS 34-35 CHELSEA 36 BOW 37 DERBY 38 CAUGHLEY—COALPORT 39-41 WORCESTER 42-43 G. GRAINGER & CO 43 LOWESTOFT 44 DOULTON 44-46 BELLEEK—W. -

Decorative Arts,Design & Interiors

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Decorative Arts,Design & Interiors Tuesday 5th January 2021 at 10.00 Viewing on a rota basis by appointment only Special Auction Services Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL Telephone: 01635 580595 Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Harriet Mustard Helen Bennett Nick Forrester Antiques & Antiques & Antiques & Fine Art Fine Art Fine Art Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price 1. A large 20th Century Chinese 6. A quantity of glassware to 14. A quantity of silver plated wares 21. A clear glass pharmaceutical 30. A 20th Century squat cut glass 37. An early 18th Century issue sancai glazed statue of a horse after the include a Victorian blue opaline raised to include mid century modern jug and type bottle of substantial proportions decanter with multifaceted spherical of ‘The Primer set forth by the Kings Tang, a/f with loss to ear, 66.5cm x 64cm bowl with foliated edging and floral sugar bowl on tapered legs, the jug 5cm labelled ‘Liq:Ferri.Iod: 1 to 7’, height stopper, height 27cm, together with majesty and his clergy’, psalms, prayer, -

Auction Results Srandr10124 Wednesday, 05 February 2020

Auction Results srandr10124 Wednesday, 05 February 2020 Lot No Description 1 A loose set of epns Kings pattern flatware and cutlery for six place-settings (72pcs) £40.00 2 A 19th century electroplated urn-shaped samovar with twin scrolled handles and scallop-carved wooden tap, on stemmed £40.00 square base. 47 cm high 3 £50.00 An oak canteen containing a set of OEP flatware (little used) to/w another canteen containing mixed electroplated flatware (2) 4 An Edwardian brass-mounted mahogany two-drawer canteen, containing a mixed set of OEP and other flatware, condiments £85.00 Aetc mahogany to/w an oak-cased boxed case part of set twelve of electroplated electroplated fish fish knives knives and and forks forks, (2) to/w a Victorian ivory-handled set of six fish knives and 5 forks and a pair of fish servers with silver-mounted ivory handles, Sheffield 1925 and a carving knife and fork with silver- £30.00 mounted antler handles - all a/f (box) 6 An epns Art Deco teapot and hot water jug from Barkers of Kensington to/w an oak canteen of electroplated flatware and ivory- £45.00 handled cutlery and two cased sets of flatware and cutlery (5) 7 An epns Jersey cream and sugar pair on stand, a three-piece tea service, trophy cup and other items (box) £30.00 8 A set of three seven-sconce (six branch) candelabra on baluster stems 36 cm high (3) £120.00 9 A walnut canteen table with two fitted drawers, containing a part set of electroplated flatware for twelve settings (ivory-handled £50.00 knives and forks removed) 10 Various electroplated wares including -

BRITISH and EUROPEAN CERAMICS and GLASS | Knightsbridge, London | Monday 2 November 2015 22841

BRITISH AND EUROPEAN CERAMICS AND GLASS Monday 2 November 2015 Knightsbridge, London BRITISH AND EUROPEAN CERAMICS GLASS | Knightsbridge, London Monday 2 November 2015 22841 BRITISH AND EUROPEAN CERAMICS AND GLASS Monday 2 November 2015 at 10.30am and 2.30pm Knightsbridge, London VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Friday 30 October +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Glass Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm 9am – 4.30pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax John Sandon +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Saturday 31 October To bid via the internet please +44 (0) 20 7468 8244 11am – 3pm visit bonhams.com [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder Sunday 1 November information including after-sale 11am – 3pm Please note that telephone British Ceramics collection and shipment bidding is only available on Fergus Gambon SALE NUMBER lots with the low estimate in +44 (0) 20 7468 8245 IMPORTANT INFORMATION 22841 excess of £500. Bids should be [email protected] The United States Government submitted no later than 4pm on has banned the import of ivory CATALOGUE the day prior to the sale. New European Ceramics into the USA. Lots containing £25.00 bidders must also provide proof Sophie von der Goltz ivory are indicated by the symbol of identity when submitting bids. +44 (0) 20 7468 8349 Ф printed beside the lot number Failure to do this may result in [email protected] in this catalogue. your bid not being processed. General Enquiries LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS [email protected] AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE [email protected] Please email [email protected] with ‘live bidding’ in the subject line 48 hours before the auction to register for this service Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams 1793 Ltd Directors Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No.