On Rottnest Island: Potential for the Nurse Practitioner Role

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

DR. EVELYN E. GAISER George M. Barley, Jr. Endowed Chair, Institute of Environment Professor, Department of Biological Sciences Florida International University Miami, FL 33199 305-348-6145 (phone), 305-348-4096 (fax), [email protected] EDUCATION 1997 Ph.D. University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, Institute of Ecology 1991 M.S. Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa, Department of Animal Ecology 1989 B.S. Kent State University, Kent, Ohio, Department of Biology ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2018-present George M. Barley, Jr. Endowed Chair of Everglades Research, Institute of Environment, Florida International University, Miami, FL 2014 – 2018 Executive Director, School of Environment, Arts and Society and Associate Dean, College of Arts, Sciences and Education, Florida International University, Miami, FL 2012-present Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, FL 2006-2012 Associate Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, FL 2008-present Research Associate, Archbold Biological Station, Lake Placid, FL 2001- 2006 Assistant Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, FL 1997-2001 Assistant Research Scientist, Southeast Environmental Research Center, Florida International University, Miami, FL 1991-1997 Research/Teaching Assistant, Institute of Ecology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA and Savannah River Ecology Lab, Aiken, SC 1989-1991 Research/Teaching Assistant, Department of Animal Ecology, Iowa State University, Ames, IA and Iowa Lakeside Laboratory, Milford, IA 1987-1988 Research Technician, Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, Ohio State University, Wooster, OH ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE AT FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY 2014 – 2018 Executive Director, School of Environment, Arts and Society and Associate Dean, College of Arts, Sciences and Education. I served as the academic leader of one of three schools in the College of Arts, Sciences and Education. -

Patterns of Propeller Scarring of Seagrass in Florida Bay

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior South Florida Natural Resources Center Everglades National Park RESOURCE EVALUATION REPORT SFNRC Technical Series 2008:1 PATTERNS OF PROPELLER SCARRING OF SEAGRASS IN FLORIDA BAY Associations with Physical and Visitor Use Factors and Implications for Natural Resource Management PATTERNS OF PROPELLER SCARRING OF SEAGRASS IN FLORIDA BAY Associations with Physical and Visitor Use Factors and Implications for Natural Resource Management RESOURCE EVALUATION REPORT SFNRC Technical Series 2008:1 South Florida Natural Resources Center Everglades National Park Homestead, Florida National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Cover photograph of north end of Lower Arsnicker Key by Lori Oberhofer, ENP ii South Florida Natural Resources Center Technical Series (2008:1) Patterns of Propeller Scarring of Seagrass in Florida Bay iii Patterns of Propeller Scarring of Seagrass in Florida Bay: Associations with Physical and Visitor Use Factors and Implications for Natural Resource Management RESOURCE EVALUATION REPORT SFNRC Technical Series 2008:1 EXECUTive SummarY of approximately 10, i.e., there may be as many as 3250 miles of scars in Florida Bay. Everglades National Park (ENP) encompasses over 200,000 Substantially more scarring was identified in this study hectares of marine environments, including most of Florida than in a previous study conducted in 1995. Bay. The ENP portion of Florida Bay was federally designated as submerged wilderness in 1978. Much of Florida Bay sup- ports submerged aquatic vegetation comprised of seagrass Patterns and Associations that provides vast areas of habitat for recreationally and com- mercially important fish and invertebrates. Florida Bay is a The majority of scarring was identified in depths below 3.0 premier shallow-water recreational fishing destination and it ft and scarring density tends to increase with decreasing is heavily used by recreational boaters for access to produc- depth. -

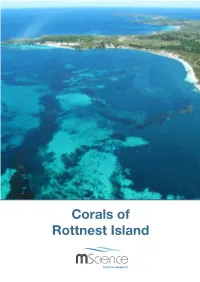

Corals of Rottnest Island Mscience Pty Ltd June 2012 Volume 1, Issue 1

Corals of Rottnest Island MScience Pty Ltd June 2012 Volume 1, Issue 1 MARINE RESEARCH Produced with the Assistance of the Rottnest Island Authority Cover picture courtesy of H. Shortland Jones * Several of the images in this publication are not from Rottnest and were sourced from corals.aims.gov.au courtesy of Dr JEN Veron Contents What are hard corals? ...........................................................................................4 Corals at Rottnest Island .....................................................................................5 Coral Identification .............................................................................................5 Hard corals found at Rottnest Island ...............................................................6 Faviidae ............................................................................................................7 Acroporidae and Pocilloporidae ....................................................................11 Dendrophyllidae ............................................................................................13 Mussidae ......................................................................................................15 Poritidae .......................................................................................................17 Siderastreidae ..............................................................................................19 Coral Identification using a customised key ................................................21 Terms used -

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

Cockburn Sound's World War II Anti

1 Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Project aims and methodology Historical background Construction of the World War II Cockburn Sound naval base and boom defences Demolition and salvage Dolphin No.60 2010 site inspections Conclusions Significance Statement of cultural significance Legal protection Recommendations References Appendix 1 – GPS Positions 2 Acknowledgements Thanks to Jeremy Green, Department of Maritime Archaeology for geo- referencing the Public Works Department plans. Thanks to Joel Gilman and Kelly Fleming at the Heritage Council of Western Australia for assistance with legal aspects of the protection of the Dolphin No.60 site. Thanks to Mr Earle Seubert, Historian and Secretary, Friends of Woodman Point for providing valuable information regarding the history and demolition of the boom net and Woodman Point sites. Also to Mr Gary Marsh (Friends of Woodman Point) and Mr Matthew Hayes (Operations Manager, Woodman Point Recreation Camp). Matt Carter thanks the Our World Underwater Scholarship Society (OWUSS) and Rolex for enabling him to assist the WA Museum with this project. Thanks to Marie-Amande Coignard for assistance with the diving inspections. Thanks to Timothy Wilson for the cover design. Cover images Public Works Department Plan 29706 Drawing No.7 Dolphin No.60 (National Archives of Australia) Diver inspecting Dolphin No.60 site (Patrick Baker/ WA Museum) Type ‘A’ anti-boat hurdles (Australian War Memorial) 3 Introduction The Cockburn Sound anti-submarine boom defences were a major engineering project undertaken during World War II to protect the approaches to Cockburn Sound, and the northern boom defences spanned 9.37 km of seabed. In 1964 the timber pylons and dolphins were demolished with explosives and the steel nets were cut and dropped onto the seabed (Jeffery 1988). -

P|Lf Llte^?*F• ^J^'F'^'»:Y^-^Vv1;' • / ' ^;

Poisonous Animals of the Desert Item Type text; Book Authors Vorhies, Charles T. Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Rights Public Domain: This material has been identified as being free of known restrictions under U.S. copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights. Download date 29/09/2021 16:26:58 Item License http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194878 University of Arizona College of Agriculture Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin No. 83 j ^.^S^^^T^^r^fKK' |p|p|lf llte^?*f• ^j^'f'^'»:Y^-^Vv1;' • / ' ^; Gila Monster. Photograph from life. About one-fifth natural size. Poisonous Animals of the Desert By Charles T. Vorhies Tucson, Arizona, December 20, 1917 UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION GOVERNING BOARD (REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY) ttx-Officio His EXCELLENCY, THE GOVERNOR OF ARIZOX v THE STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUULIC INSTRUCTION Appointed by the Governor of the State WILLI\M V. WHITMORE, A. M., M. D Chancellor RUDOLPH R VSMESSEN Treasurer WILLIAM J. BRY VN, JR., A, B Secretary vViLLi \M Sc \RLETT, A. B-, B. D Regent JOHN P. ORME Regent E. TITCOMB Regent JOHN W. FUNN Regent CAPTAIN J. P. HODGSON Regent RLIFUS B. \ON KLEINSMITI, A. M., Sc. D President of the University Agricultural Staff ROBERT H. FORBES, Ph. D. Dean and Director JOHN J. THORNBER, A. M Botanist ALBERT E. VINSON, Ph. D Biochemist CLIFFORD N. CATLJN, A, M \ssistunt Chemist GEORGE E. P. SMITH, C. E Irrigation Engineer FRANK C. KELTON, M. S \ssistnnt Engineer GEORGE F. -

The Global Distribution and Status of Seagrass Ecosystems

The global distribution and status of seagrass ecosystems ^^ ^^^H Discussion paper prepared for tlie UNEP-WCWIC Global Seagrass Workshop St Pete's Beach, Florida, 9 November, 2001 Prepared by: Mark D. Spalding, Michelle L. Taylor, Sergio Martins, Edmund P. Green, and Mary Edwards WA.. WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2010 witii funding from UNEP-WCIVIC, Cambridge Iittp://www.archive.org/details/globaldistributi01spal The global distribution and status of seagrass ecosystems Discussion paper prepared for tlie UNEP-WCIVIC Global Seagrass Workshop St Pete's Beach, Florida, 9 November, 2001 Prepared by: Mark D. Spalding, Michelle L. Taylor, Sergio Martins, Edmund P. Green, and Mary Edwards With assistance from: Mark Taylor and Corinna Ravilious Table of Contents Introduction to the workshop 2 The global distribution and status of seagrass ecosystems 3 Introduction 3 Definitions 3 The diversity of seagrasses 3 Species distribution 4 Associated Species 6 Productivity and biomass 7 The distribution and area of seagrass habitat 8 The value of seagrasses 13 Threats to seagrasses 13 Management Interventions 14 Bibliography; 16 29 Annex 1 : Seagrass Species Lists by Country Annex 2 - Species distribution maps 34 Annex 3 - Seagrass distribution maps 68 74 Annex 4 -Full list of MPAs by country ; /4^ ] UNEP WCMC Introduction to the workshop The Global Seagrass Workshop of 9 November 2001 has been set up with the expressed aim to develop a global synthesis on the distribution and status of seagrasses world-wide. Approximately 20 seagrass experts from 14 counu-ies, representing all of the major seagrass regions of the world have been invited to share their knowledge and expertise. -

Clinical Inbox

Clinical Documentation in AED AED Poisoning Case Management Form Dr. Joseph Yao Health Informatics Hong Kong Hospital Authority Poisoning incidents are common Background • According to The Hong Kong Poison Information Centre (HKPIC), there were around 4,000 poisoning cases reported in 2010 in Hong Kong • Most of the patients were admitted via AEDs and received immediate treatment • The Poison Form was developed to align with the enhanced features of CMS III, as well as the readiness for electronic clinical documentation in AEDs Efficiency Challenges in AED • High patient volume • Timing critical Mobility • Interacting with multiple patients and team members at any one time • Vast variety of clinical conditions • Sentinel point for the whole Knowledge community support • ….. Connect to the Community Goal ... • Full electronic clinical documentation in AEDs • Poisoning Case Management Form as a trial Most cases are clinically less critical Data items standardized Case load not too heavy AED record Free Text Future interface Induce frontline staff to adopt electronic documentation at AEDs Acquisition Institutionalization % of User Adoption Adoption Trial Use Understanding Awareness Contact Time How do we record Poisoning Cases in AEDs?? Current situation • Poisoning cases in A&E are manually recorded: i. Handwritten AED card ii. Locally-developed manual forms • Wide range of non-standardized information captured among different hospitals. Limited standardized data captured in A&D card Limitations • Difficult to retrieve information based -

Zootaxa, Mollusca, Vetigastropoda

ZOOTAXA 714 New species of Australian Scissurellidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda) with remarks on Australian and Indo-Malayan species DANIEL L. GEIGER & PATTY JANSEN Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand DANIEL L. GEIGER & PATTY JANSEN New species of Australian Scissurellidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda) with remarks on Australian and Indo-Malayan species (Zootaxa 714) 72 pp.; 30 cm. 4 November 2004 ISBN 1-877354-66-X (Paperback) ISBN 1-877354-67-8 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2004 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41383 Auckland 1030 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2004 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 714: 1–72 (2004) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 714 Copyright © 2004 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) New species of Australian Scissurellidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda) with remarks on Australian and Indo-Malayan species DANIEL L. GEIGER1 & PATTY JANSEN2 1 Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, 2559 Puesta del Sol Road, Santa Barbara, CA 93105, USA. E- mail: [email protected] 2 P. O. Box 345, Lindfield, NSW 2070, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] Table of contents Abstract . -

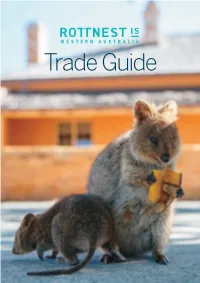

Trade Guide Contents

WESTERN AUSTRALIA Trade Guide Contents Welcome to Rottnest Island 3 How to get to Rottnest Island 4 Visit all year round 5 A peaceful Class A nature reserve 5 Getting around 6 Rottnest Island’s top ten experiences 7 Accommodation 9 Dining and Refreshments 10 Internationally Ready Product 11 Rottnest Island business contacts 16 Rottnest Island map 18-19 All details correct at time of printing June 2021 2 Welcome to Rottnest Rottnest Island’s photogenic ambassador, Island the quokka, skyrocketed Western Australia’s favourite WESTERN AUSTRALIA’S island paradise to international fame PREMIER ISLAND ESCAPE! after high-profile celebrities including Roger Federer, Margot Robbie and Located less than 20 kilometres from Chris Hemsworth posted selfies with Western Australia’s world-renowned these cute, native marsupials on their port city of Fremantle, Rottnest Island social media channels. is an easily accessible nature No wonder quokkas are considered the lover’s paradise. happiest animals on Earth; they inhabit Rottnest Island is so close to Perth Australia’s most beautiful island. It’s easy that it’s visible from coastal vantage to see why our visitors love it here as points on clear days, which is much as they do. most often the case for Australia’s sunniest capital city. WESTERN Rottnest Island, or ‘Rotto’, as it’s AUSTRALIA affectionately known by locals, has been the destination of choice for Western Australians for generations, is also a “must see” destination for Hillarys people visiting Western Australia from interstate and overseas. Perth Rottnest Island Fremantle 3 How to get to Rottnest Island Hillarys 45 mins Rottnest Island’s pristine turquoise bays, Perth aquatic activities, walking trails, historic attractions and abundance of wildlife Rottnest Island 90 mins are just a short ferry ride from Perth, Fremantle or Hillarys Ferry Terminals. -

I&I NSW Game Fish Tagging Program

I&I NSW Game Fish Tagging Program Summary 2006/2007 & 2007/2008 I&I NSW Game Fish Tagging Program Summary and Report 2006/2007 & 2007/2008 This report of the I&I NSW Game Fish Tagging Program incorporates both the 2006/2007 and 2007/2008 game fishing seasons. The report provides a summary from each year and a detailed description of recaptures of note. Also included is an analysis of striped marlin and southern bluefin tuna recaptures since the start of the Program. The Game Fish Tagging Program, which has been operated since 1973 by NSW Fisheries (later NSW DPI and now I&I NSW), has continued strongly over these past two seasons. Large numbers of key game fish were tagged in each of these years and recaptures of tagged fish continued to add new information to our understanding of the biology of many species. As might be expected over such a long period, the number of fish tagged each year has fluctuated, although following steady growth to the mid 1980s, in nearly all years since then, the total tagged has exceeded 10,000 (Figure 1 – number of tagged fish in dark blue, number of recaptures in light blue). Three of the last four years of the Program saw more than 14,000 fish tagged, followed by a slight drop in the 2007/2008 season. This drop was attributable to a relatively poor season in the Cairns black marlin fishery, the lower abundance of juvenile black marlin along the east coast, and generally bad weather during the New South Wales summer fishing season which restricted the number of days fished. -

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants used by Maonan people in China Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine S(2015)ample 11:32 doi:10.1186/s13002-015-0019-1 Liya Hong ([email protected]) Zhiyong Guo ([email protected]) Kunhui Huang ([email protected]) Shanjun Wei ([email protected]) Bo Liu ([email protected]) Shaowu Meng ([email protected]) Chunlin Long ([email protected]) Sample ISSN 1746-4269 Article type Research Submission date 29 November 2014 Acceptance date 11 April 2015 Article URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13002-015-0019-1 For information about publishing your research in BioMed Central journals, go to http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/ © 2015 Hong et al. ; licensee BioMed Central This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants used by Maonan people in China Liya Hong1 Email: [email protected] Zhiyong Guo1 Email: [email protected] Kunhui Huang1 Email: [email protected]