It's a Big Old Goofy World View: John Prine As a Modern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Bob Denson Master Song List 2020

Bob Denson Master Song List Alphabetical by Artist/Band Name A Amos Lee - Arms of a Woman - Keep it Loose, Keep it Tight - Night Train - Sweet Pea Amy Winehouse - Valerie Al Green - Let's Stay Together - Take Me To The River Alicia Keys - If I Ain't Got You - Girl on Fire - No One Allman Brothers Band, The - Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More - Melissa - Ramblin’ Man - Statesboro Blues Arlen & Harburg (Isai K….and Eva Cassidy and…) - Somewhere Over the Rainbow Avett Brothers - The Ballad of Love and Hate - Head Full of DoubtRoad Full of Promise - I and Love and You B Bachman Turner Overdrive - Taking Care Of Business Band, The - Acadian Driftwood - It Makes No Difference - King Harvest (Has Surely Come) - Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, The - Ophelia - Up On Cripple Creek - Weight, The Barenaked Ladies - Alcohol - If I Had A Million Dollars - I’ll Be That Girl - In The Car - Life in a Nutshell - Never is Enough - Old Apartment, The - Pinch Me Beatles, The - A Hard Day’s Night - Across The Universe - All My Loving - Birthday - Blackbird - Can’t Buy Me Love - Dear Prudence - Eight Days A Week - Eleanor Rigby - For No One - Get Back - Girl Got To Get You Into My Life - Help! - Her Majesty - Here, There, and Everywhere - I Saw Her Standing There - I Will - If I Fell - In My Life - Julia - Let it Be - Love Me Do - Mean Mr. Mustard - Norwegian Wood - Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da - Polythene Pam - Rocky Raccoon - She Came In Through The Bathroom Window - She Loves You - Something - Things We Said Today - Twist and Shout - With A Little Help From My Friends - You’ve -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Donna Summer I'm a Rainbow Mp3, Flac, Wma

Donna Summer I'm A Rainbow mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock / Pop Album: I'm A Rainbow Country: UK Released: 2014 Style: New Wave, Synth-pop, Ballad, Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1747 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1376 mb WMA version RAR size: 1977 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 283 Other Formats: MP4 MPC AAC VOX VOC AHX AU Tracklist Hide Credits I Believe (In You) 1-1 4:31 Vocals [Duet With] – Joe "Bean" Esposito*Written-By – Harold Faltermeyer, Keith Forsey True Love Survives 1-2 3:36 Written-By – Donna Summer, Pete Bellotte You To Me 1-3 4:39 Written-By – Pete Bellotte, Sylvester Levay Sweet Emotion 1-4 3:44 Written-By – Pete Bellotte, Sylvester Levay Leave Me Alone 1-5 4:04 Written-By – Harold Faltermeyer, Keith Forsey Melanie 1-6 3:38 Written-By – Donna Summer, Giorgio Moroder Back Where You Belong 1-7 3:52 Written-By – Harold Faltermeyer, Keith Forsey People Talk 1-8 4:15 Written-By – Donna Summer, Giorgio Moroder To Turn The Stone 1-9 4:20 Written-By – Giorgio Moroder, Pete Bellotte Brooklyn 2-1 4:35 Written-By – Donna Summer, Pete Bellotte, Sylvester Levay I'm A Rainbow 2-2 4:06 Written-By – Bruce Sudano Walk On (Keep On Movin') 2-3 3:49 Written-By – Giorgio Moroder, Pete Bellotte Don't Cry For Me Argentina 2-4 4:22 Written-By – Andrew Lloyd Webber, Tim Rice A Runner With The Pack 2-5 4:06 Written-By – Pete Bellotte Highway Runner 2-6 3:27 Written-By – Donna Summer, Giorgio Moroder Romeo 2-7 3:13 Written-By – Pete Bellotte, Sylvester Levay End Of The Week 2-8 3:38 Written-By – Pete Bellotte, Sylvester Levay I Need Time 2-9 4:23 Written-By – Donna Summer, Giorgio Moroder, Pete Bellotte Companies, etc. -

Elvis Costello Began Writing Songs at the Age of Thirteen. 2017 Marked the 40Th Anniversary of the Release of His First Record Album, My Aim Is True

Elvis Costello began writing songs at the age of thirteen. 2017 marked the 40th anniversary of the release of his first record album, My Aim Is True. He is perhaps best known for the songs, “Alison”, “Pump It Up”, “Everyday I Write The Book” and his rendition of the Nick Lowe song, “(What’s So Funny ‘Bout) Peace Love and Understanding”. His record catalogue of more than thirty albums includes the contrasting pop and rock & roll albums: This Year’s Model, Armed Forces, Imperial Bedroom, Blood and Chocolate and King Of America along with an album of country covers, Almost Blue and two collections of orchestrally accompanied piano ballads, Painted From Memory - with Burt Bacharach and North. He has performed worldwide with his bands, The Attractions, His Confederates - which featured two members of Elvis Presley’s “T.C.B” band - and his current group, The Imposters – Steve Nieve, Pete Thomas and Davey Faragher - as well as solo concerts, most recently his acclaimed solo show, “Detour”. Costello has entered into songwriting collaborations with Paul McCartney, Burt Bacharach, the Brodsky Quartet and with Allen Toussaint for the album The River In Reverse, the first major label recording project to visit New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and completed there while the city was still under curfew. In 2003, Costello acted as lyrical editor of six songs written with his wife, the jazz pianist and singer Diana Krall for her album, The Girl In The Other Room. He has written lyrics for compositions by Charles Mingus, Billy Strayhorn and Oscar Peterson and musical settings for words by W.B. -

Yesterday and Today Records March 2007 Newsletter

March 2007 Newsletter ----------------------------------- Yesterday & Today Records 255A Church St Parramatta NSW 2150 phone/fax: (02) 96333585 email: [email protected] web: www.yesterdayandtoday.com.au ------------------------------------------------------ Postage: 1 cd $2.00/ 2cd $3/ 3-4 cds $5.80* (*Recent Australia Post price increase.) Guess what? We have just celebrated our 18th anniversary. Those who try things we recommend are rewarded. We have stayed in business for one reason and that is we have never attempted to appeal to the lowest common denominator as mainstream outlets do. At the same time we recognise that people do have different tastes and to some CMT is actually good. We also appeal to those people and offer many mainstream items in our bargain bin. But the legends and true country music are our bread butter and will always be. If you see something you think you may like but are worried let us know. If you pass our inquisition we may be able to send it on a sale or return basis. I say inquisition because if your favourite artists are SheDaisy and Rascal Flatts we certainly aren’t going to risk something as precious as Justin Trevino. By the same token we believe great music is timeless and knows no bounds. People may think chuck steak is good until they try the best rump! Recently I had the pleasure of seeing Dale Watson. Before hand I had the added pleasure of sitting in with my compatriot Eddie White (a.k.a. “The Cosmic Cowboy”) for an interview at the 2RRR Studios. Dale is a humble, engaging and extremely likeable man with a passion for tradition. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Closer Final Song Blonde Dangerous Woman 1 the Chainsmokers Feat

29 August 2016 CHART #2049 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Closer Final Song Blonde Dangerous Woman 1 The Chainsmokers feat. Halsey 21 M0 1 Frank Ocean 21 Ariana Grande Last week 2 / 4 weeks Disruptor/SonyMusic Last week 24 / 6 weeks SonyMusic Last week - / 1 weeks BoysDon'tCry Last week 26 / 14 weeks Republic/Universal Cold Water Cheap Thrills Suicide Squad OST All Over The World: The Best Of 2 Major Lazer feat. Justin Bieber And... 22 Sia 2 Various 22 ELO Last week 1 / 5 weeks Gold / Because/Warner Last week 23 / 27 weeks Platinum x2 / Inertia/Rhythm Last week 1 / 3 weeks Atlantic/Warner Last week 24 / 19 weeks Gold / SonyMusic Let Me Love You This Girl 25 Lemonade 3 DJ Snake feat. Justin Bieber 23 Kungs And Cookin' On 3 Burners 3 Adele 23 Beyonce Last week 3 / 3 weeks Interscope/Universal Last week 22 / 8 weeks KungsMusic/Universal Last week 4 / 40 weeks Platinum x7 / XL/Rhythm Last week 34 / 18 weeks Gold / Columbia/SonyMusic Heathens Starving Views A Head Full Of Dreams 4 Twenty One Pilots 24 Hailee Steinfeld And Grey feat. Zedd 4 Drake 24 Coldplay Last week 4 / 10 weeks Gold / Atlantic/Warner Last week - / 1 weeks Republic/Universal Last week 3 / 17 weeks CashMoney/Universal Last week - / 33 weeks Gold / Parlophone/Warner Don't Worry Bout It Hurts So Good Blurryface Kaleidoscope World 5 Kings 25 Astrid S 5 Twenty One Pilots 25 The Chills Last week 7 / 7 weeks Gold / ArchAngel/Warner Last week 18 / 5 weeks Universal Last week 2 / 33 weeks Gold / FueledByRamen/Warner Last week - / 11 weeks FlyingNun/FlyingOut One Dance Never Be Like You Poi E: The Story Of Our Song Major Key 6 Drake feat. -

Live and Die Down to the River to Pray (Oh Brother

THE AVETT BROTHERS Live and Die GEORGE HARRISON If Not For You PETE SEEGER If I had a Hammer ALISON KRAUSS Down to The River to Pray GEORGE HARRISON My Sweet Lord RICHIE HAVENS Here Comes The Sun (Oh Brother Where Art Thou?) GILLIAN WELCH Dear Someone RUFUS WAINWRIGHT Hallelujah THE BAND The Weight GILLIAN WELCH I’ll Fly Away (Oh Brother Where Art Thou?) RYAN ADAMS When The Stars Go Blue BONNIE RAITT Angel From Montgomery GRATEFUL DEAD Cold Rain And Snow THE SHINS New Slang BIG STAR 13 HANK WILLIAMS Jambalaya TOWNES VAN ZANDT I’ll Be Here In The Morning BLIND WILLIE JOHNSON John The Revelator JACKSON BROWN These Days TOWNES VAN ZANDT White Freightliner Blues BOB DYLAN Lay, Lady Lay JOAN BAEZ House of The Rising Sun THE TRIO Do I Ever Cross Your Mind BON IVER Skinny Love JOHN DENVER Take Me Home, Country Roads THE VELVET UNDERGROUND Pale Blue Eyes BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN I’m on Fire JOHNNY CASH Ring of Fire THE ZOMBIES This Will Be Our Year THE BYRDS You Aint Going Nowhere JOHN PRINE/ BONNIE RAITT Up Above My Head VAN MORRISON Astral Weeks CANNED HEAT Going Up The Country JONI MITCHELL California WILCO California Stars THE CARTER FAMILY Keep on the Sunny Side JOSE GONZALEZ Heartbeats WILLIE NELSON Always on My Mind CAT POWER Sea of Love THE KINKS Strangers WOODY GUTHRIE Hard Travelin’ CAT STEVENS Here Comes My Baby LED ZEPPELIN Tangerine DOLLY PARTON Jolene LOUDON WAINWRIGHT Daughter DUSTY SPRINGFIELD Son Of A Preacher Man LOUVIN BROTHERS My Baby’s Gone EAGLES One of These Nights LOUVIN BROTHERS You’re Running Wild EDWARD SHARPE Home THE LUMINEERS Ho Hey EVERLY BROTHERS All I Have To Do Is Dream NEIL YOUNG Harvest Moon EVERLY BROTHERS Down In The Willow Garden NEIL YOUNG Unknown Legend THE FACES Ooh La La OLD CROW MEDICINE SHOW Wagon Wheel FAIRPORT CONVENTION Who Knows Where the Time Goes? PAUL SIMON Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes FLEET FOXES Mykonos PAUL SIMON Me and Julio Down by The Schoolyard FLEETWOOD MAC Never Going Back Again PENNY & QUARTERS You And Me . -

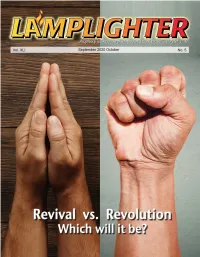

Lamplighter Sep/Oct 2020

Observations by the Editor Gloom and Doom Dr. David R. Reagan Now may the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in be- The Lamplighter lieving, so that you will abound in is published bi-monthly hope by the power of the Holy by Lamb & Lion Ministries Spirit (Romans 15:13). Mailing Address: received a message recently from a P.O. Box 919 McKinney, TX 75070 Igentleman who wrote to complain about our publishing too many negative Telephone: 972/736-3567 Email: [email protected] articles. He suggested that we write more Website: www.lamblion.com about hope. b b b b b b b b b I was surprised by his complaint be- Chairman of the Board: cause each of our staff members who Mark Strickland write for this magazine always try to end Dr. David R. Reagan Founder & Senior Evangelist: our articles with an assurance of hope. Believers even have the hope of escape Dr. David R. Reagan We have done that consistently since the from this steadily darkening world of im- Chief Operating Officer: beginning of the ministry in 1980. morality and violence. That hope is called Rachel Houck the Rapture of the Church, which will occur What has changed is that in the de- before the Great Tribulation begins. Yes, Associate Evangelist: cade of the 80s, we would usually con- Tim Moore Church Age believers — both the living and clude any article about our nation by the dead — will be taken off this planet Internet Evangelist: pointing the reader to 2 Chronicles 7:14, Nathan Jones before God begins pouring out His wrath on asking them to pray for a spiritual revival the world’s rebellious nations. -

Most Requested Songs of 2016

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2016 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Ronson, Mark Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 6 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 7 Swift, Taylor Shake It Off 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 10 Sheeran, Ed Thinking Out Loud 11 Williams, Pharrell Happy 12 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 13 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 14 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 15 Mars, Bruno Marry You 16 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 17 Maroon 5 Sugar 18 Isley Brothers Shout 19 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 20 B-52's Love Shack 21 Outkast Hey Ya! 22 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 23 Legend, John All Of Me 24 DJ Snake Feat. Lil Jon Turn Down For What 25 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 26 Timberlake, Justin Can't Stop The Feeling! 27 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 28 Beatles Twist And Shout 29 Earth, Wind & Fire September 30 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 31 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 32 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 33 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 34 Spice Girls Wannabe 35 Temptations My Girl 36 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 37 Silento Watch Me 38 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 39 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 40 Jordan, Montell This Is How We Do It 41 Sister Sledge We Are Family 42 Weeknd Can't Feel My Face 43 Dnce Cake By The Ocean 44 Flo Rida My House 45 Lmfao Feat.