Trans Men Actors Resisting Cisnormative Theatrical Traditions with Phenomenal Stage Presence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Rochester

THE UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER In keeping with the nature of the ceremonies and in order that all may see and hear with out distraction, it is requested that those in attendance refrain from smoking and conversation during the ceremonies and from moving onto the floor to take photographs. Your cooperation will be greatly appre ciated. An asterisk preceding the name indicates that the degree is conferred subject to the completion of certain re quirements. COMMENCEMENT HYMN 0 Ma-ter a - ca- de-mi-ca Ro- ces-tri-en-sis, te Quae no-bis tan-ta 0 Ma-ter,quam cog-no-vi-mus per lae-ta tem-po-ra, Quae demonstrasti f 0 Ma-ter, a-ve, sal-ve, tu, va- le, ca-ris-si-ma! Nos ju-vat jam in ~~~,F. Dr J I J F F ~J I ~J. J I J r r J I F. ; J J I mu-ne-ra de- dis-ti 1i - be - re Nunc sa- lu - ta - mus, a-gi-mus nos om-ni-bus la- bo-ris gau- di- a, Quae "Me-li- o - ra" in-di- cas, ex- ex -i - tu dul -cis me- mo- r1- a. Per· vii':'\as due nos as-pe - ras sem- ,~~ J r r F I f' · J I J r F r IF f J J I J J J J I d. II ti- bi gra-ti- as, Et sem-per te lau-da- imus cui no-men ve - ri - tas. eel-sa praemi- a, Ad cae-lum om-nes in-ci-tas, tu Ma- ter splen-di- da! per ad op- ti - rna; Mer-ce-des da per pe-tu-as, bo-na cae-les - ti - a! 1907 -JOHN ROTHWELL SLATER English translation of Commencement Hymn 0 Rochester, our college mother, who hast freely given us so great gifts, we salute thee now, we thank thee, and will ever praise thee, whose name is Truth. -

Sociology 210B Gender, Class, and Race Spring 2017 Brandeis

Sociology 210b Gender, Class, and Race Spring 2017 Brandeis University Professor Karen V. Hansen Wed. 2 to 4:50 Pearlman Hall 209 Pearlman 203 781-736-2651 Office Hours: Wed 10 to 12 [email protected] & by appointment Course Description This course examines the ways that gender, class, and race are conceptualized, constituted, and interpreted. Beginning with gender, it will explore contrasting intersectional theoretical approaches as well as methodological questions and empirical studies. How do social structures and individual agency intertwine to produce gendered, raced, and classed individuals? How are structures reproduced through institutions and action over time and generation? How is change accomplished? The class will examine power and inequality embedded and reinforced in social structures, everyday practices, and internalized identities. It does not seek to be exhaustive. Rather, it introduces students to a range of perspectives that provide analytic tools for asking questions about the social world, interrogating assumptions of theoretical paradigms, assessing empirical research, and constructing an intersectional study. This exploration involves asking epistemological questions. How do we know what we know? As sociologists, in our efforts to surface and analyze patterns of sometimes invisible or elusive social phenomena, at every turn we are going to ask questions about method and sources. If we want to understand inequality from multiple perspectives, including that of the dispossessed, disempowered, and oppressed, how do we gain access to them? Where do we find narratives and experience from these groups? How do we assess and interpret them? How do we adapt our angle of vision given our respective social location? Choose our analytic tools? Assess intersecting structures of inequality? This seminar explores these theoretical and methodological issues through deep engagement with the HistoryMakers Digital Archive, a collection of over 1,600 oral histories with African Americans now available at Brandeis. -

The Inventory of the Sam Shepard Collection #746

The Inventory of the Sam Shepard Collection #746 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Shepard, Srun Sept,1~77 - Jan,1979 Outline of Inventory I. MANUSCRIPTS A. Plays B. Poetry c. Journal D. Short Prose E. Articles F. Juvenilia G. By Other Authors II. NOTES III. PRINTED MATTER A, By SS B. Reviews and Publicity C. Biographd:cal D. Theatre Programs and Publicity E. Miscellany IV. AWARDS .•, V. FINANCIAL RECOR.EB A. Receipts B. Contracts and Ageeements C. Royalties VI. DRAWINGS AND PHOTOGRAPHS VII. CORRESPONDENCE VIII.TAPE RECORDINGS Shepard, Sam Box 1 I. MANUSCRIPTS A. Plays 1) ACTION. Produced in 1975, New York City. a) Typescript with a few bolo. corr. 2 prelim. p., 40p. rn1) b) Typescript photocopy of ACTION "re-writes" with holo. corr. 4p. marked 37640. (#2) 2) ANGEL CITY, rJrizen Books, 1976. Produced in 1977. a) Typescript with extensive holo. corr. and inserts dated Oct. 1975. ca. 70p. (ft3) b) Typescript with a few holo. corr. 4 prelim. p., 78p. (#4) c) Typescript photocopy with holo. markings and light cues. Photocopy of r.ouqh sketch of stage set. 1 prelim. p., 78p. ms) 3) BURIED CHILD a) First draft, 1977. Typescript with re~isions and holo. corr. 86p. (#6) b) Typescript revisions. 2p. marked 63, 64. (#6) 4) CALIFORNIA HEART ATTACK, 1974. ,•. ' a) Typescript with holo. corr. 23p. (#7) ,, 5) CURSE OF THE STARVING CLASS, Urizen Books, 1976. a) Typescript with holo. corr. 1 prelim. p., 104p. ms) b) Typescript photocopy with holo. corr. 1 prelim. p. 104p. (#9) c) Typescript dialogue and stage directions, 9p. numbered 1, 2, and 2-8. -

Trans Men Actors Resisting Cisnormative Theatrical Traditions with Phenomenal Stage Presence

UCLA Queer Cats Journal of LGBTQ Studies Title Dys-appearing/Re-Appearing: Trans Men Actors Resisting Cisnormative Theatrical Traditions with Phenomenal Stage Presence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/79w7t2v8 Journal Queer Cats Journal of LGBTQ Studies, 2(1) ISSN 2639-0256 Author Cole, Joshua Bastian Publication Date 2018 DOI 10.5070/Q521038307 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Dys-appearing/Re-Appearing: Trans Men Actors Resisting Cisnormative Theatrical Traditions with Phenomenal Stage Presence Joshua Bastian Cole Cornell University “To some, I will never be a ‘real man’ no matter how skilled my portrayal. Maybe, then, I will always be just an actor.”— Scott Turner Schofield, “Are We There Yet?” “What makes us so confident that we know what’s real?”—Jamison Green, Becoming a Visible Man Acting Cis Traditional actor training espouses “bodily unity,” or unobstructed access to all parts of the physiological (and expectedly able) body; anything else would be what Jerzy Grotowski calls “biological chaos.”1 A focus on bodily unity in actor training implies that an alternate, dysphoric, or oth- erwise non-normative embodied experience is “chaotic”—an obstacle to overcome, unhealthy and unwhole—and that embodied disconnections signify failure or lack. This attitude toward disjointedness, when applied to transgender embodiment, infers that trans people are nothing more than broken cisgender people.2 But the trans “whole” body offers an alternative conception of “wholeness,” one with empty spaces creating a fragmented human form. For trans men, that fragmentation localizes around the chest and pelvis, but the empty spaces that emerge there create healthier and more peaceful versions of embodiment for many trans people. -

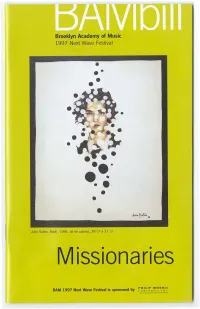

Missionaries

Brooklyn Academy of Music 1997 Next Wave Festival .•- •• • •••••• ••• • • • • Julio Galan, Rado, 1996, oil on canvas, 39 '/>" x 31 W' Missionaries PHILIP MORRIS BAM 1997 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by COMPANIES INC. Brooklyn Academy of Music Bruce C. Ratner Chairman of the Board Harvey Lichtenstein President and Executive Producer presents Missionaries Running time: BAM Majestic Theater approximately November 4-8, 1997 at 7:30pm two hours and twenty minutes Conceived, composed and directed by Elizabeth Swados including one intermission Produced by Ron Kastner, Peter Manning and New York Stage and Film Cast Dorothy Abrahams, Vanessa Aspillaga, Carrie Crow, Josie de Guzman, Pierre Diennet, Marisa Echeverria, Abby Freeman, Peter Kim, Gretchen Lee Krich, Fabio Polanco, Nick Petrone, Heather Ramey, Nina Shreiber, Tina Stafford, Rachel Stern, Amy White Musical direction and piano David Gaines Percussion Genji Ito, Bill Ruyle Guitar Ramon Taranco Cello / keyboards J. Michael Friedman Lighting design Beverly Emmons Costu me design Kaye Voyce Production manager Jack O'Connor General manager Christina Mills Production stage manager Judy Tucker Co-commissioned by Brooklyn Academy of Music Major support provided by ==:ATaaT and The Ford Foundation ~ Missionaries is meant to honor the memory of those who were killed in EI Salvador during the terrible times of the 1970s and 1980s. I hope it will also bring attention to the extraordinary efforts being made today by the MADRES and other groups devoted to stopping violence and bringing freedom and dignity to the poor. Jean Donovan, Dorothy Kazel, Ita Ford, and Maura Clarke were murdered because of their beliefs and dedication to the women and children of EI Salvador. -

GULDEN-DISSERTATION-2021.Pdf (2.359Mb)

A Stage Full of Trees and Sky: Analyzing Representations of Nature on the New York Stage, 1905 – 2012 by Leslie S. Gulden, M.F.A. A Dissertation In Fine Arts Major in Theatre, Minor in English Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. Dorothy Chansky Chair of Committee Dr. Sarah Johnson Andrea Bilkey Dr. Jorgelina Orfila Dr. Michael Borshuk Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Leslie S. Gulden Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to my Dissertation Committee Chair and mentor, Dr. Dorothy Chansky, whose encouragement, guidance, and support has been invaluable. I would also like to thank all my Dissertation Committee Members: Dr. Sarah Johnson, Andrea Bilkey, Dr. Jorgelina Orfila, and Dr. Michael Borshuk. This dissertation would not have been possible without the cheerleading and assistance of my colleague at York College of PA, Kim Fahle Peck, who served as an early draft reader and advisor. I wish to acknowledge the love and support of my partner, Wesley Hannon, who encouraged me at every step in the process. I would like to dedicate this dissertation in loving memory of my mother, Evelyn Novinger Gulden, whose last Christmas gift to me of a massive dictionary has been a constant reminder that she helped me start this journey and was my angel at every step along the way. Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………ii ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………..………………...iv LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………..v I. -

The Drive of Queer Exceptionalism: Transgender Authenticity As Queer Aesthetic Levi Hord Western University, [email protected]

Western University Scholarship@Western 2017 Undergraduate Awards The ndeU rgraduate Awards 2017 The Drive of Queer Exceptionalism: Transgender Authenticity as Queer Aesthetic Levi Hord Western University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/undergradawards_2017 Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Hord, Levi, "The Drive of Queer Exceptionalism: Transgender Authenticity as Queer Aesthetic" (2017). 2017 Undergraduate Awards. 14. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/undergradawards_2017/14 Hord 1 The Drive of Queer Exceptionalism: Transgender Authenticity as Queer Aesthetic Levi C. R. Hord In “Judith Butler: Queer Feminisms, Transgender and the Transubstantiation of Sex”, Jay Prosser suggests that queer communities have appropriated the symbols of gender transition, exposing the “mechanism by which queer can sustain its very queerness […] by periodically adding subjects who appear ever queerer precisely by virtue of their marginality in relation to queer” (279). Situating this claim in a contemporary context, I will develop this line of thought by suggesting that transgender embodiment (or the symbolic aesthetic of it) has become a marker of queer authenticity1. Immersed in a culture where transgender narratives are defined by movement towards an “authentic self,” transgender bodies have come to signify as expression of realness. In this essay, I will argue that combining the assumption of transgender authenticity and the individualism of queer neoliberal exceptionalism works not only to appropriate transition as a symbol to affirm the queerness of “queer”, but to affirm gender ambiguity as the epitome of authentic queer embodiment. Thus, genderqueerness has not only become part of a queer political critique, but may function to explain shifts in queer selfhood, proliferations of trans identifications from within queer communities, and ongoing border wars. -

An Actor Remembers: Memory's Role in the Training of the United States

An Actor Remembers: Memory’s Role in the Training of the United States Actor by Devin E. Malcolm B.A. in The Human Drama, Juniata College, 1997 M.A. in Theatre, Villanova University, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre History and Performance Studies University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Devin E. Malcolm It was defended on November, 5th 2012 and approved by Kathleen George, PhD, Theatre Arts Bruce McConachie, PhD, Theatre Arts Edouard Machery, PhD, History and Philosophy of Science Dissertation Advisor: Attilio Favorini, PhD, Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Devin E. Malcolm 2012 iii AN ACTOR REMEMBERS: MEMORY’S ROLE IN THE TRAINING OF THE UNITED STATES ACTOR Devin E. Malcolm, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This dissertation examines the different ways actor training techniques in the United States have conceived of and utilized the actor’s memory as a means of inspiring the actor’s performance. The training techniques examined are those devised and taught by Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, Joseph Chaikin, Stephen Wangh and Anne Bogart and Tina Landau. As I shall illustrate, memory is not the unified phenomenon that we often think and experience it to be. The most current research supports the hypothesis that the human memory is composed of five distinctly different, yet interrelated systems. Of these five my research focuses on three: episodic, semantic, and procedural. -

Transfeminisms

Cáel M. Keegan—Sample syllabus (proposed) This is a proposed syllabus for an advanced WGSS seminar. Transfeminisms Course Overview:_________________________________________________ Description: Recent gains in visibility and recognition for transgender people have reactivated long- standing arguments over whether feminism can or should support trans rights, and whether transgender people should be considered feminist subjects. Rather than re- staging this decades-long debate as a zero-sum game, this course traces how—far from eradicating each other—“trans” and “feminist” share a co-constitutive history, each requiring and evolving the other. To quote Jack Halberstam from his talk "Why We Need a Transfeminism" at UC Santa Cruz in 2002, “Transgender is the gender trouble that feminism has been talking about all along.” We will explore the unfolding of the transfeminist imaginary from its roots in gay liberation and woman of color feminisms, through the sex wars of the 1970s and 80s, and into the 21st century. Throughout, we will examine a number of key points in feminist discourse and politics at which the paradoxical formation “transfeminism” becomes legible as a framework, necessity, legacy, or impending future. We will uncover transfeminist histories and grapple with the complexity of transfeminist communities, activisms, and relations. We will explore transfeminist world-building and practice our own transfeminist visions for the world. Required Text: Transgender Studies Quarterly, “Trans/Feminisms.” Eds. Susan Stryker and Talia Mae Bettcher. 3.1-2 (May 2016). The required text is available at the bookstore. All other readings are available via electronic reserve on Blackboard. Required Films: Films are on course reserve for viewing at the library. -

Documentary Theatre, the Avant-Garde, and the Politics of Form

“THE DESTINY OF WORDS”: DOCUMENTARY THEATRE, THE AVANT-GARDE, AND THE POLITICS OF FORM TIMOTHY YOUKER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Timothy Earl Youker All rights reserved ABSTRACT “The Destiny of Words”: Documentary Theatre, the Avant-Garde, and the Politics of Form Timothy Youker This dissertation reads examples of early and contemporary documentary theatre in order to show that, while documentary theatre is often presumed to be an essentially realist practice, its history, methods, and conceptual underpinnings are closely tied to the historical and contemporary avant-garde theatre. The dissertation begins by examining the works of the Viennese satirist and performer Karl Kraus and the German stage director Erwin Piscator in the 1920s. The second half moves on to contemporary artists Handspring Puppet Company, Ping Chong, and Charles L. Mee. Ultimately, in illustrating the documentary theatre’s close relationship with avant-gardism, this dissertation supports a broadened perspective on what documentary theatre can be and do and reframes discussion of the practice’s political efficacy by focusing on how documentaries enact ideological critiques through form and seek to reeducate the senses of audiences through pedagogies of reception. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS iii INTRODUCTION: Documents, Documentaries, and the Avant-Garde 1 Prologue: Some History 2 Some Definitions: Document—Documentary—Avant-Garde -

Along with Peter Brook and Jerzy Grotowski, Joseph Chaikin Is One of the Main Forces in the Last Two Decades Showing Us Who the Actor Is

Along with Peter Brook and Jerzy Grotowski, Joseph Chaikin is one of the main forces in the last two decades showing us who the actor is. For several dozen years plus Joe's devotion to excellence has challenged us. Theatre artists around the world recognize his tremendous contribution to the growth of the idea of a purposeful theatre. His vision of theatre is not restricted to linear plot and psychological naturalism. He has tuagh1 us the importance of association and counterpoint. He has shown us that the visual image is at least as important as the spoken word. Joe's idea of theatre is a'blend of the pers onal, poli tical and metaphysical. Sam Shepard says that Joe is the main force in American Theatre. The Stanislavski viewpoint about acting · encourages the actor to merge his personality with the character. Through Joe's work we can now know that who the person is on. stage is also part of the theatre process, and that person must not be lost. Joe Chaikin began his career in the early 60's by heading to New York to be discovered so he could make movies and become famous and rich. Not long after he was in the B.i&Jppel, however, he began work with The Living Theatre, and thos~:amoltions did not prevail. In 1963, he started the Open Theatre, a loosely knit group of artists who experiment• with voic.e, mov~emen t, and the relationships between performers and spectators. Then ·in 1973 . the Open Theatre separated, and Joe r..eturnoclcnd·i~<J.,.t-< t-e- actir::f and directing, and star ted The Winter Project. -

Living Theatre for Immediate Release the Brooklyn Academy of Music March 20, 1975 30 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn, N.Y.11217 Press Office ( 212) 636-4123

8Affl Living Theatre For Immediate Release The Brooklyn Academy of Music March 20, 1975 30 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn, N.Y.11217 Press Office ( 212) 636-4123 Brooklyn Academy of Music and Universal Movement Theatre Repertory will present a benefit for The Living Theatre Collective's newest work, a cycle of plays called The Legacy of Cain --- An Open Discussion On Theatre Now with Julian Beck Joseph Chaikin Judith Malina Richard Schechner and the Entire Audience Wednesday evening, April 23, 1975, 8:00pm, Lepercq Space. Donation: $4.00. TDF vouchers accepted. For information and reservations: 212-989-2207. The Living Theatre's productions of Paradise Now, Frankenstein, Mysteries and Smaller Pieces and Antigone (seen in performances at BAM during the company's 1968-69 United States tour) are among the works which have earned its reputation as one of the most important American theatrical groups of this generation. The Living Theatre has been influential not only in the United States but also in Europe where the company toured extensively between 1961-70. In 1970-71 The Living Theatre went to Brazil where work on The Legacy of Cain began. The Legacy of Cain includes a variety of theatrical forms, many of which are planned to be performed in non-theatrical environments: streets, factories and mills, social halls, churches, gymnasiums, parks, schools, hospitals, empty lots and prisons. The forms which the plays will take include parades, a street carnival, a tower 40 feet high to be erected in the open air, a labyrinth, oratoriums, action pieces, children's plays, pieces for television and radio, games, rituals and dream plays.