The Return to Sinjar Education Health WASH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gurriculum Vitae

حوكمةتا هةريَما كوردستانىَ – عرياق حكومت أقليم كودستان – العراق وزارة التعليم العالي والبحث العلمي وةزراتا خوندنا باﻻ وتوذينيَت زانستى رئاست جامعت بولينكنيك دهوك سةوركاتيا زانلويا ثوليتةكنيلا دهوك Kurdistan Regional Government-Iraq Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Duhok Polytechnic University Curriculum Vitae University Address: 61 Zahko Road, 1006 Mazi Qt., Duhok , Kurdistan -Iraq A / Personal data Name: Mohammed Haydar Mosa Date of Birth: 1/1/1971 Place of Birth: Mosul City \ lraq Marital Status: Married Mother Tongue: Kurdish Other Language: Kurdish, English and Arabic Degree: M.Sc. Nursing from Nursing College/ Mosul University\ Iraq 2005 B\Educational University University Collage Degree Date (Year) Specialty Mosul Mosul Technical Technical Diploma 199 - 1993 Anesthesia Institute\Iraq Institute\Iraq Mosul College of Nursing B.SC 1994 - 1998 University Nursing Science Mosul College of Pediatric M.SC 2003 - 2005 University Nursing health nursing C\Training and education: Name ,Place , Country Type Years attended Academic degree obtained From To Tumor workshop \ Tumor 21/9/1996 - 29/9/1996 Training Mosul \Iraq nursing Second conference tumor Tumor 22/9/1996 - 24/9/1996 Training Of Mosul \Iraq Course & methods to teach public health\ Community 12 October 2004 Training Community health health nursing - 15 October 2004 nursing \ Duhok \ Iraq Cardiac catheterization Cardiac \ Azadi teaching 2007 Training catheterization hospital \Duhok\ Iraq Methods of education Methods of \Duhok Technical 4/7/2009 - 18/7/2006 education institute \Iraq Evaluation of health Environmental states At health Institutions In 7th scientific conference conference 27-28 September 2010 Iraq. Mosul proceedings university\Nursing collage The role of Scientific research in Developing 10th National scientific of public health . -

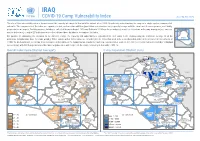

COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020

IRAQ COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020 The aim of this vulnerability index is to understand the capacity of camps to deal with the impact of a COVID-19 outbreak, understanding the camp as a single system composed of sub-units. The components of the index are: exposure to risk, system vulnerabilities (population and infrastructure), capacity to cope with the event and its consequences, and finally, preparedness measures. For this purpose, databases collected between August 2019 and February 2020 have been analysed, as well as interviews with camp managers (see sources next to indicators), a total of 27 indicators were selected from those databases to compose the index. For purpose of comparing the situation on the different camps, the capacity and vulnerability is calculated for each camp in the country using the arithmetic average of all the IRAQ indicators (all indicators have the same weight). Those camps with a higher value are considered to be those that need to be strengthened in order to be prepared for an outbreak of COVID-19. Each indicator, according to its relevance and relation to the humanitarian standards, has been evaluated on a scale of 0 to 100 (see list of indicators and their individual assessment), with 100 being considered the most negative value with respect to the camp's capacity to deal with COVID-19. Overall Index Score (District Average*) Camp Population (District Sum) TURKEY TURKEY Zakho Zakho Al-Amadiya 46,362 Al-Amadiya 32 26 3,205 DUHOK Sumail DUHOK Sumail Al-Shikhan 83,965 Al-Shikhan Aqra -

Irak : Situation Sécuritaire Dans Le District De Sinjar

Irak : situation sécuritaire dans le district de Sinjar Recherche rapide de l’analyse-pays Berne, 28 novembre 2018 Conformément aux standards COI, l’OSAR fonde ses recherches sur des sources accessibles publiquement. Lorsque les informations obtenues dans le temps imparti sont insuffisantes, elle fait appel à des expert -e-s. L’OSAR documente ses sources de manière transparente et traçable, mais peut toutefois décider de les anony- miser, afin de garantir la protection de ses contacts. Impressum Editeur Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés (OSAR) Case postale, 3001 Berne Tél. 031 370 75 75 Fax 031 370 75 00 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.osar.ch CCP dons: 10-10000-5 Versions français, allemand COPYRIGHT © 2018 Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés (OSAR), Berne Copies et impressions autorisées sous réserve de la mention de la source 1 Introduction Le présent document a été rédigé par l’analyse-pays de l’Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés (OSAR) à la suite d’une demande qui lui a été adressée. Il se penche sur les ques- tions suivantes: Quelle est la situation sécuritaire dans le district de Sinjar (province de Ninawa) ? L’ « État islamique » (EI) autoproclamé /Daesh est-il encore présent ou représente-il encore une menace dans ce district ? 1. Quels sont les principaux obstacles au retour des personnes déplacées et à la recons- truction dans le district de Sinjar ? 2. Est-il concevable qu'un enfant mineur irakien d'origine kurde, qui a passé plusieurs mois dans un camp de l’EI/Daesh dans le district de Sinjar, puisse à son retour subir des me- sures de représailles de la part de la population locale ? Pour répondre à ces questions, l’analyse-pays de l’OSAR s’est fondée sur des sources ac- cessibles publiquement et disponibles dans les délais impartis (recherche rapide) ainsi que sur des renseignements d’expert-e-s. -

On Her Shoulders

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE ON HER SHOULDERS Lead Sponsor Exclusive Education Partner Supported by An agency of the Government of Ontario Un organisme du gouvernement de l’Ontario Additional support is provided by The Andy and Beth Burgess Family Foundation, the Hal Jackman Foundation, J.P. Bickell Foundation and through contributions by Like us on Facebook.com/docsforschools individual donors. WWW.HOTDOCS.CA/YOUTH HEADER ON HER SHOULDERS Directed by Alexandria Bombach 2018 | USA | 94 min In English, Kurmanji and Arabic, with English subtitles TEACHER’S GUIDE This guide has been designed to help teachers and students enrich their experience of On Her Shoulders by providing support in the form of questions and activities. There are a range of questions that will help teachers frame discussions with their class, activities for before, during and after viewing the film, and some weblinks that provide starting points for further research or discussion. The Film The Filmmaker Having seen and experienced the atrocities committed Alexandria Bombach is an award-winning cinematographer, against the Yazidi community in Iraq, Nadia Murad becomes editor and director from Santa Fe, New Mexico. Her feature- the reluctant but powerful voice of her people in a crusade to length documentary On Her Shoulders follows Nadia Murad, get the world to finally pay attention to the genocide taking a 23-year-old Yazidi woman who survived genocide and place. The 23-year-old survived repeated sexual assaults and sexual slavery committed by ISIS. In addition to her feature bore witness to the ruthless murders of her loved ones. Now, documentary work, Alexandria’s production company Red her bravery to speak openly is put to the test daily as Reel has been producing award-winning, character-driven reporters, politicians and activists push for her to recount stories since 2009. -

Iraq: Opposition to the Government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Opposition to the government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) Version 2.0 June 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

COI Note on the Situation of Yazidi Idps in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

COI Note on the Situation of Yazidi IDPs in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq May 20191 Contents 1) Access to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KR-I) ................................................................... 2 2) Humanitarian / Socio-Economic Situation in the KR-I ..................................................... 2 a) Shelter ........................................................................................................................................ 3 b) Employment .............................................................................................................................. 4 c) Education ................................................................................................................................... 6 d) Mental Health ............................................................................................................................ 8 e) Humanitarian Assistance ...................................................................................................... 10 3) Returns to Sinjar District........................................................................................................ 10 In August 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham (ISIS) seized the districts of Sinjar, Tel Afar and the Ninewa Plains, leading to a mass exodus of Yazidis, Christians and other religious communities from these areas. Soon, reports began to surface regarding war crimes and serious human rights violations perpetrated by ISIS and associated armed groups. These included the systematic -

In the Aftermath of Genocide

IN THE AFTERMATH OF GENOCIDE Report on the Status of Sinjar 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS expertise, foremost the Yazidi families who participated in this work, but also a number of other vital contributors: ADVISORY BOARD Nadia Murad, Founder of Nadia’s Initiative Kerry Propper, Executive Board Member of Nadia’s Initiative Elizabeth Schaeffer Brown, Executive Board Member of Nadia’s Initiative Abid Shamdeen, Executive Board Member of Nadia’s Initiative Numerous NGOs, U.N. agencies, and humanitarian aid professionals in Iraq and Kurdistan also provided guidance and feedback for this report. REPORT TEAM Amber Webb, lead researcher/principle author Melanie Baker, data and analytics Kenglin Lai, data and analytics Sulaiman Jameel, survey enumerator co-lead Faris Mishko, survey enumerator co-lead Special thanks to the team at Yazda for assisting with the coordination of this report. L AYOUT AND DESIGN Jens Robert Janke | www.jensrobertjanke.com PHOTOGRAPHY Amber Webb, Jens Robert Janke, and the Yazda Documentation Team. Images should not be reproduced without authorization. reflect those of Nadia’s Initiative. To protect the identities of those who participated in the research, all names have been changed and specific locations withheld. For more information please visit www.nadiasinitiative.org. © FOREWORD n August 3rd, 2014 the world endured yet another genocide. In the hours just before sunrise, my village and many others in the region of Sinjar, O Iraq came under attack by the Islamic State. Tat morning, IS militants began a campaign of ethnic cleansing to eradicate Yazidis from existence. In mere hours, many friends and family members perished before my eyes. Te rest of us, unable to flee, were taken as prisoners and endured unspeakable acts of violence. -

Refugee Status Appeals Authority New Zealand

REFUGEE STATUS APPEALS AUTHORITY NEW ZEALAND REFUGEE APPEAL NO 76505 AT AUCKLAND Before: B L Burson (Chairperson) S A Aitchison (Member) Counsel for the Appellant: D Mansouri-Rad Appearing for the Department of Labour: No Appearance Date of Hearing: 3 & 4 May 2010 Date of Decision: 14 June 2010 DECISION [1] This is an appeal against the decision of a refugee status officer of the Refugee Status Branch (RSB) of the Department of Labour (DOL) declining refugee status to the appellant, a national of Iraq. INTRODUCTION [2] The appellant claims to have a well-founded fear of being persecuted in Iraq on account of his former Ba’ath Party membership in the rank of Naseer Mutakadim, and due to his father’s position as Branch Member of the al-Amed Organisation for the Ba’ath Party in City A. He fears persecution at the hands of members of the Mahdi Army – a Shi’a militia group in Iraq, the police who collaborate with them, and the Iraqi Government that is infiltrated by militias. [3] The principal issues to be determined in this appeal are the well- foundedness of the appellant’s fears and whether he can genuinely access meaningful domestic protection. 2 THE APPELLANT’S CASE [4] What follows is a summary of the appellant’s evidence in support of his claim. It will be assessed later in this decision. Background [5] The appellant is a single man in his early-30s. He was born in Suburb A in City A. He is one of three children, the youngest of two boys. -

Iraq 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAQ 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Iraq is a constitutional parliamentary republic. The 2018 parliamentary elections, while imperfect, generally met international standards of free and fair elections and led to the peaceful transition of power from Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi to Adil Abd al-Mahdi. On December 1, in response to protesters’ demands for significant changes to the political system, Abd al-Mahdi submitted his resignation, which the Iraqi Council of Representatives (COR) accepted. As of December 17, Abd al-Mahdi continued to serve in a caretaker capacity while the COR worked to identify a replacement in accordance with the Iraqi constitution. Numerous domestic security forces operated throughout the country. The regular armed forces and domestic law enforcement bodies generally maintained order within the country, although some armed groups operated outside of government control. Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) consist of administratively organized forces within the Ministries of Interior and Defense, and the Counterterrorism Service. The Ministry of Interior is responsible for domestic law enforcement and maintenance of order; it oversees the Federal Police, Provincial Police, Facilities Protection Service, Civil Defense, and Department of Border Enforcement. Energy police, under the Ministry of Oil, are responsible for providing infrastructure protection. Conventional military forces under the Ministry of Defense are responsible for the defense of the country but also carry out counterterrorism and internal security operations in conjunction with the Ministry of Interior. The Counterterrorism Service reports directly to the prime minister and oversees the Counterterrorism Command, an organization that includes three brigades of special operations forces. The National Security Service (NSS) intelligence agency reports directly to the prime minister. -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

Kurdistan Regional Government

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/13/2021 9:45:57 AM Newroz Video Message from KRG Representation in USA 1 message Kurdistan Regional Government - USA <[email protected]> Sun, Mar 21,2021 at 1:28 PM Reply-To: [email protected] To: [email protected] Kurdistan Regional Government Representation in the United States Washington D.C. Newroz Video Message from KRG Representation in USA Every year we look forward to celebrating Newroz, the Kurdish new year, and the arrival of spring on March 21st. Through gatherings with family, friends, and community, we also celebrate our people's liberation from tyranny and demonstrate support for the Kurdish cause. Regrettably, this year, we had to celebrate Newroz far away from each other due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, on March 5th, we invited you to submit a short video Newroz message of yourself or with your loved ones, answering the question: what does Newroz mean to you or remind you of? The answer is in this video. Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/13/2021 9:45:57 AM Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/13/2021 9:45:57 AM piroa ©e 9fa^/?y Aft jro/ Sign Up for KRG Updates Share the Podcast Follow us Share Tweet Share oo NOTIFICATION: The Kurdistan Regional Government Liaison Office - U.S.A. is registered as an agent of the Kurdistan Regional Government under 22 U.S.C. § 611 et seq. | 1532 16th Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036 Unsubscribe [email protected] Update Profile | Customer Contact Data Notice Sent by [email protected] powered by Constant Contact ©Try email marketing for free today! Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/13/2021 9:45:57 AM Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/13/2021 9:45:57 AM Reminder: KRG-US March 2021 newsletter 1 message Kurdistan Regional Government - USA <[email protected]> Sat, Apr 3, 2021 at 6:13 PM Reply-To: [email protected] To: [email protected] Kurdistan Regional Government Representation in the United States Washington D.C. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project.