The Case of Australian Wine Producers*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUSTRALIA > Australia

Endeavour Group Limited. ABN: Page 1 of 7 Untitled Document All sales subject to the conditions printed in this catalogue Created on: 30/09/2021 6:17:26 PM HX825 - Explore NSW & ACT 9:00 PM Tuesday, June 9, 2015 A Buyers Premium of 15% excluding GST applies to all lots. All lots sold GST inclusive, except where marked '#'. AUSTRALIA > Australia A-E Lot No Description Vintage Quantity Bottle Winning Price Classification 1 ANGULLONG Taplow Maze Cabernet, Central Ranges. Screwcap Closure. 2011 2 Bottle Passed In 2 BRINDABELLA HILLS WINERY Riesling, Canberra District. Screwcap 2013 1 Bottle $10.0000000000 Closure. 00000000 3 BRINDABELLA HILLS WINERY Riesling, Canberra District. Screwcap 2014 2 Bottle $10.0000000000 Closure. 00000000 4 BRINDABELLA HILLS WINERY Riesling, Canberra District. Screwcap 2014 3 Bottle $10.0000000000 Closure. 00000000 5 BRINDABELLA HILLS WINERY Riesling, Canberra District. Screwcap 2014 6 Bottle Passed In Closure. 6 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. 1996 1 Bottle $120.000000000 Exceptional 000000000 7 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. Minor 1996 1 Bottle Passed In Exceptional Label Stain/s. 8 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. 1996 2 Bottle Passed In Exceptional 9 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. 1996 2 Bottle Passed In Exceptional 10 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. Minor 1996 3 Bottle Passed In Exceptional Label Stain/s. 11 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. 2001 1 Bottle $84.0000000000 Exceptional 00000000 12 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. 2001 2 Bottle $76.0000000000 Exceptional 00000000 13 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. -

Total Entries 2006 Competition

Page 1 TOTAL ENTRIES 2006 COMPETITION WINERY PARTICULAR NAME VINT MAIN GRAPE & % OTHERS & % STATE 3 BRIDGES CABERNET SAUVIGNON - WESTEND ESTATE 2002 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 90 PETIT VERDOT 10 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES CABERNET SAUVIGNON - WESTEND ESTATE SHOW RESERVE2003 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 90 PETIT VERDOT 10 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES CHARDONNAY - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 CHARDONNAY 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES DURIF- WESTEND ESTATE 2003 DURIF 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES RESERVE DURIF - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 DURIF 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES MERLOT - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 MERLOT 85 PETIT VERDOT 15 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES RESERVE BOTRYTIS - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 SEMILLON 60 PEDRO XIMENEZ 40 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES BOTRYTIS SEMILLON - WESTEND ESTATE GOLDEN MIST2003 SEMILLON 85 PEDRO XIMENEZ 15 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES BOTRYTIS SEMILLON - WESTEND ESTATE 2004 SEMILLON 85 PEDRO XIMENEZ 15 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES SHIRAZ - WESTEND ESTATE 2002 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES SHIRAZ - WESTEND ESTATE SHOW RESERVE 2003 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES SHIRAZ - WESTEND ESTATE LIMITED RELEASE RESERVE2003 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW 3 BROTHERS WINERY GISBORNE CHARDONNAY 2004 CHARDONNAY 100 NZ 3 BROTHERS WINERY WAIRARAPA PINOT NOIR 2004 PINOT NOIR 90 MALBEC 10 NZ 3 BROTHERS WINERY MARLBOROUGH SAUVIGNON BLANC 2005 SAUVIGNON BLANC 100 NZ ABERCORN A RESERVE' VINTAGE PORT 2004 CABERNET 100 A/NSW ABERCORN A RESERVE' SHIRAZ 2003 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW ABERCORN NJILLA 2004 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW ABERCORN GROWERS REVENGE 2002 SHIRAZ 40 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 40A/NSW ADINFERN ESTATE SHIRAZ 2004 SHIRAZ 100 A/WA ALCIRA VINEYARD NUGAN ESTATE 2002 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 100 A/SA ALLAN SCOTT WINES -

In the Time It Has Taken James Halliday to Compile His 26 Australian Wine

In the time it has taken James Halliday to compile his 26 Australian Wine Companions, the Chardonnay grape has emigrated to almost every hill and vale across our viticultural landscape. No other variety has adapted more successfully, from single barrel selections to vast commercial blends. No other inspires such singular focus in our winemakers to sharpen their craft. No other sends vignerons searching, with gold fever, for that next hill, or clone, or aspect. Chardonnay alone explores the breadth and personality of all Australian wine regions. In our tribute to James Halliday, the true patron of fine Australian wine, no other variety would do for this national wine competition. Organised by Wine Yarra Valley, the objective of the James Halliday Chardonnay Challenge is to affirm the quality of Australian Chardonnay and provide a catalyst for people to take a fresh look at this much-loved wine by providing an appropriate platform for the national search to recognize Australia’s finest chardonnay. A Welcome from the Committee Australian chardonnay has never been better. It is a great news story and one about which we should all be proud and excited. The level of support for the inaugural James Halliday Chardonnay Challenge has been overwhelming and we thank all of the exhibitors for getting behind it so enthusiastically. We thank James for his guidance and support in the design and execution of the competition and agreeing to be our patron. We were very lucky to be able to secure one of the most dynamic and talented groups of judges in Australia, literally from coast-to-coast, and thank them for volunteering their time, expertise and camaraderie. -

Company Guest List

COMPANY GUEST LIST 1847 Wines/Chateau Yaldara Flinders University Accolade Wines Freight Hub Logistics Adelaide Hospital Goodiesons Brewery Amorim Australasia Grounded Cru ASVO Hardy Wines ATEC Haselgrove Wines Australian Vintage Hawk Engineering Australian Wine Research Institute Hydra Consulting AV Plus John Duval Wines Barossa Enterprises Kalleske Wines Barossa Grape & Wine Kauri Barrel Finance & Logistics Kilikanoon Ben Murray Wines Kirri Hill Wines Bentleys (SA) Langmeil Winery Berg Herring Wines Limestone Coast Tourism Berry to Wine LJ Hooker Blue H2O Filtration MEA Business SA MGA Insurance Brokers Capital Evolution Group Nepenthe Chubb Insurance Ocvitti Clean Machine Ord Minnett Cold Logic Orora Core Sponsorship Patrick Iland Wine Promotions Cornershop Design Patrick of Coonawarrs Cragg Cru Wines Patritti Crane Creative Paxton Vineyards Dabblebrook Wines Penley Estate d’Arenberg Pernod Ricard Winemakers Dell’uva Wines Pirathon Denomination Port Adelaide Football Club DTTI Qantas DW Fox Tucker Red Seed Eight at the Gate Wines Revel Global Fastrak Asian Solutions Rusty Mutt COMPANY GUEST LIST Savant Energy vinCreative Scholle IPN Vinous Consulting Seppeltsfield Wines Visy Shottesbrooke Vineyards VoltSaver Sidewood Estate Waterfind SITIA WBM Somerled Wine Australia Stainless Engineering & Maintenance Wine Collaborators Stirling Vineyard Services Wine Communicators of Australia SULLIVAN Consulting Wine Grape Council of South Australia Taglog Australia Wine In A Glass Taylors Wines Wine Tourism Australia The Blok Estate Coonawarra Winegrapes Australia The Lane WineWorks The Pawn Wine Co WISA Thorn-Clarke Wines Wombaroo Treasury Wine Estates Yalumba Family Winemakers University of South Australia Z WINE Thank you to our Award and Event Partners:. -

2018 Results

2018 Adelaide Hills Saint Martin Wine Show CLASS 01 SPARKLING WINE - NV, 2018 AND 2017 VINTAGE Judges: Pablo Theodoras, Bryan Martin, Josephine Perry, Matt L Laube, Matt T Turnbull Entered: 20 Class comments: Top wine great example of sparkling rose, fresh fruit, with complexity and lovely aroma. All wines Judged: 20 that got a medal were lovely drinking bubbles. ENTRY # EXHIBITOR FULL WINE NAME SCORE AWARD 1 Artwine Artwine 2018 Prosecco 85 Bronze 2 Bird in Hand Bird in Hand 2018 Sparkling Pinot Noir 87 Bronze 3 Howard Vineyard Howard Vineyard 2018 Clover Pinot Noir, 90 Silver Chardonnay 4 Wicks Estate Wicks Estate 2018 Sparkling Chardonnay, Pinot 86 Bronze Noir 5 Lambrook Wines Lambrook Wines 2018 'Spark' Sparkling Pinot 85 Bronze Noir 6 Barristers Block Premium Barristers Block 2017 Poetic Justice Sparkling Wines Blush Pinot Noir 7 Lloyd Brothers Wines Lloyd Brothers 2017 Piper Alexandra Sparkling Chardonnay 8 Paracombe Premium Wines Paracombe NV 2017 Release Pinot Noir, Chardonnay 9 Jo Irvine Pty Ltd Levrier by Jo Irvine NV Brut Rose Petit Meslier 10 Unico Zelo Unico Zelo NV Harvest Chardonnay 90 Silver 11 Chain of Ponds Chain of Ponds NV Diva Sparkling Chardonnay 85 Bronze Pinot Noir 12 Accolade Wines Petaluma Wines NV Croser Rose Pinot Noir 13 Grounded Cru Grounded Cru NV Sparkling Pinot Noir, 87 Bronze Chardonnay 14 Shottesbrooke Vineyards Shottesbrooke NV 1337 Heritage Series Blanc 91 Silver de Blancs Chardonnay 15 Accolade Wines Petaluma NV Croser Pinot Noir, Chardonnay 89 Bronze 16 Deviation Road Deviation Road NV Altair Brut -

Tasting Room Program Download

*Conditions apply, ask your store for more details. l’art de vivre by roche bobois Photo: Michel Gibert. Special thanks: Juan Antonio Sánchez Morales - www.adhocmsl.com - “Pieuvre” www.ekaacosta.com - TASCHEN. Manufactured in Europe. Beach Bay modular sofa, design Philippe Bouix Ovni cocktail tables, design Vincenzo Maiolino VANCOUVER CALGARY 716 West Hastings 225 10th Avenue SW Tel. 604-633-5005 Tel. 403-532-4401 [email protected] [email protected] Com plimentary 3D Interior Design Service* Showroom, collections, news and catalogs www.roche-bobois.com THE 37TH VANCOUVER INTERNATIONAL WINE FESTIVAL FEBRUARY 20 - MARCH 1, 2015 1,750+ wines * 170 wineries * 14 countries * 53 events * 8 days * 25,000 attendees Welcome to the 2015 Vancouver International Wine Festival, Canada’s premier wine show. This annual TABLE OF CONTENTS celebration of the grape has become a February highlight in Vancouver, with a full slate of wine tastings and WELCOME MESSAGES .................................................................................5 parties, lunches, brunches and dinners, seminars, and a three-day FESTIVAL PARTNERS.....................................................................................7 conference for trade professionals. The heart of VanWineFest, however, PARTICIPATING WINERIES ............................................................................8 is the International Festival Tastings, where all 170 wineries gather TASTING ROOM MAP...................................................................................9 -

Alternative and Extraordinary Australia

ALTERNATIVE AND EXTRAORDINARY AUSTRALIA MASTER CLASS AND FREE POUR TASTING WEDNESDAY, 17 APRIL 2019 BEDRIJVENCENTRUM DE PUNT, GENT Wine regions Welcome of Australia Darwin We’re delighted to be back in Belgium, following a successful event in Antwerp last year, sharing our wines and stories in Gent for the first time. Australia has thousands of wineries, dotted throughout 65 wine regions across the country. Our unique climate and vast landscape enables us to produce an incredibly diverse range of wine, which can be seen in more than 130 different INDIAN OCEAN grape varieties. NORTHERN TERRITORY At this master class, led by The Wine Detective, Sarah Ahmed, we’ll explore the country’s climatic diversity, winemaking brilliance and innovative spirit. QUEENSLAND Through these 12 wines, you’ll discover how Australian winemakers are experimenting with alternative varieties and new styles to create something WESTERN AUSTRALIA extraordinary. The line-up will showcase Mediterranean grape varieties and their unique style in Australia, as well as unusual and rare varieties. 28 South Eastern Australia* The master class is followed by a free pour tasting of Australia’s classic whites SOUTH AUSTRALIA Brisbane and summer reds. Taste fresh, elegant and iconic styles of Australian wine, 29 from Hunter Valley Semillon to Clare Valley Riesling, Mornington Peninsula 30 Pinot Noir to McLaren Vale Grenache. This is a great opportunity to revisit hero NEW SOUTH WALES styles as well as find out what’s coming out of Australia today. 1 31 2 Perth 10 32 33 3 GREAT 11 Exports of Australian wine continue to grow globally and there is positive 44 34 PACIFIC OCEAN AUSTRALIAN BIGHT 12 14 35 4 15 6 13 36 growth across a number of markets in Europe. -

WI 2010 Brochure 1:Layout 1

THE WINE INNOVATION AWARDS RESULTS 2009 WINE INNOVATION 2009 The Wine Innovation Awards were The awards are open to new and corners of the winemaking world. Our launched in 2009 by the drinks business existing producers who have started Business Awards were equally popular to recognise and reward the creative in fresh winemaking projects – a first with particularly high entry levels in the wine. The awards were established to vintage, a new launch or an experiment. green and ethical categories. highlight the work of those brand Every winemaker from anywhere around These awards have obviously owners and winemakers who are the world is welcome to enter as long as caught the imagination of the wine innovating and making top-quality wines the people behind the wine are world and we are very much looking – whether in the vineyard or the winery dedicated to innovation. forward to the second year of – and give the winners the opportunity The response to the Wine Innovation the Wine Innovation Awards and to shout about how they are changing Awards in its first year has been discovering the wine world’s most the face of modern winemaking. excellent with entries coming in from all innovative winemakers. THE JUDGES In 2009 we were lucky enough to count All wines entered into the Wine professionals to discover the best of the upon the experience, expertise and Innovation Awards competition were best in wine business innovation. integrity of a number of judges drawn then blind tasted by panels of industry The judges were particularly impressed from across the drinks sector – both experts and re-tasted as appropriate. -

Australia Trade Tasting 2019

AUSTRALIA TRADE TASTING 2019 30 JANUARY THE MANSION HOUSE, DUBLIN #ATTwine Wine regions Darwin Introduction of Australia Welcome to our Australia Trade Tasting. The 2018 vintage in Australia was down by We’re delighted to return to The Mansion 10% on the previous year, producing 1.79m House to host the biggest, brightest and tonnes and increasing the purchase price Indian Ocean NORTHERN most diverse showcase of Australian wine of grapes by 8%, reflecting the increased TERRITORY in Ireland. demand from the world markets. Total exports to the end of September 2018 QUEENSLAND Australia has thousands of wineries, were $2.71bn, up 11%. China is now the dotted throughout 65 wine regions across largest destination by value, growing at the country. Our unique climate and vast WESTERN AUSTRALIA 29%, followed by the USA in slight decline landscape enables us to produce an and the UK up 9%. White wine production 28 incredibly diverse range of wine, which SOUTH AUSTRALIA South Eastern Australia* returned to growth driven by a strong Brisbane can be seen in more than 100 different Chardonnay crush up 9%, while red 29 grape varieties. Australian winemakers production was down. 30 are proud creators and innovators and we Darling R NEW SOUTH WALES During the tasting, don’t miss the Women 1 31 are lucky to have the freedom to make 2 Perth 10 33 32 exceptional wine, and to do it our own in Wine Focus Table, showcasing wines Great 3 11 44 Pacific Ocean 12 14 Lachlan R 35 34 4 Australian Bight 15 6 13 36 way. -

Participating Exhibitors & Sponsors

FAR FROM ORDINARY AUSSIE WINE MONTH FAR FROM ORDINARY ROADSHOW PARTICIPATING EXHIBITORS NEW YORK CITY Accolade Wines Helen & Joey Estate Penfolds An Approach to Relaxation Henschke Penley Estate Angove Family Winemakers Hewitson Periscope Management Barossa Valley Estate Hickinbotham Clarendon Vineyard Peter Lehmann Wines Best’s Great Western Hill-Smith Family Vineyards Serafino Wines Blue Pyrenees Estate Howard Park Wines Shaw + Smith / Tolpuddle Vineyard Brockenchack Wines Hudson Wine Brokers The Chook / Thomas Goss Brothers in Arms Irvine Wines Torbreck Vintners Cabernet Corp. Jim Barry Wines Tournon Calabria Family Wines Kay Brothers Tyrrell’s Wines Campbells Wines Leconfield / Richard Hamilton Wines Vasse Felix Cape Mentelle Vineyards Living Roots Wine & Co. Vinaceous Wines Château Tanunda Mac Forbes Wines Vintage Longbottom d’Arenberg Margaret River Wine Association Wakefield Wines Dandelion Vineyards McGuigan Wines Wine Dogs Imports De Bortoli Wines McLaren Vale Grape Wine & Wine Yarra Valley Epicurean Wines Tourism Association Xanadu First Drop Wines Mo Sisters Yalumba Family Winemakers 1849 Fowles Wines Mollydooker Wines Yangarra Estate Vineyard Giant Steps Negociants USA / Winebow Yering Station / Mount Langi Ghiran Handpicked Wines Old Bridge Cellars Last updated September 13, 2019 1/5 FAR FROM ORDINARY ROADSHOW PARTICIPATING EXHIBITORS CHICAGO Accolade Wines Henschke Peter Lehmann Wines An Approach to Relaxation Hewitson The Chook / Thomas Goss Angove Family Winemakers Hickinbotham Clarendon Vineyard Torbreck Vintners Barossa -

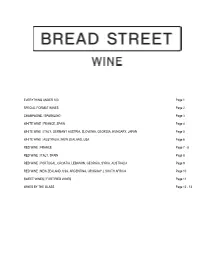

EVERYTHING UNDER 100 Page 1 SPECIAL FORMAT WINES

EVERYTHING UNDER 100 Page 1 SPECIAL FORMAT WINES Page 2 CHAMPAGNE / SPARKLING Page 3 WHITE WINE | FRANCE, SPAIN Page 4 WHITE WINE | ITALY, GERMANY AUSTRIA, SLOVENIA, GEORGIA, HUNGARY, JAPAN Page 5 WHITE WINE | AUSTRALIA,| NEW ZEALAND, USA Page 6 RED WINE | FRANCE Page 7 - 8 RED WINE | ITALY, SPAIN Page 8 RED WINE | PORTUGAL, CROATIA, LEBANON, GEORGIA, SYRIA, AUSTRALIA Page 9 RED WINE | NEW ZEALAND, USA, ARGENTINA, URUGUAY, | SOUTH AFRICA Page 10 SWEET WINES | FORTIFIED WINES Page 11 WINES BY THE GLASS Page 12 - 13 EVERYTHING UNDER 100 SPARKLING 11229 NV François Pinon, Brut, Vouvray, Loire Valley, France ……………………………………………………………… 99 11319 NV André-Michel Brégeon, Gai Perlé, Pays Nantais, Loire Valley, France ………………………………………….. 99 WHITE 11028 2015 Domaine Michel Brégeon, Muscadet Sèvre-et-Maine, Original, Loire Valley, France ……..………………… 96 11283 2015 François Cazin, Les Bisollières, Cheverny, Loire Valley, France ……………………………………………..… 98 11341 2016 Petit Chablis, William Fevre, Burgundy .............................................................................................................. 90 11027 2016 Dourthe N°1, Sauvignon Blanc, Bordeaux, France ………………………………………………………………... 89 11026 2015 Domaine de Ménard, Colombard, Côtes de Gascogne, France …………………………………………………. 78 11079 2013 Tour des Gendres, Bergerac Sec, Southwest, France …………………………………………………..…..……. 94 11254 2017 Tenuta Maccan, Pinot Grigio, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Italy ………………………………………………………….. 85 11045 2016 Pieropan, Soave Classico, Veneto, Italy ………………………………….…………………………………………. -

Sale Results Catalogue All Sales Subject to the Conditions Printed in This Catalogue Created On: 28/09/2021 10:39:39 AM

Endeavour Group Limited. ABN: Page 1 of 9 Sale Results Catalogue All sales subject to the conditions printed in this catalogue Created on: 28/09/2021 10:39:39 AM F21BQ001 - 13 SUN: Brilliant BBQ Reds Bidding closed 7:00 PM Sunday, September 13, 2020 A Buyers Premium of 15% excluding GST applies to all lots. All lots sold GST inclusive, except where marked '#'. AUSTRALIA > Australia A-E Lot No Description Vintage Quantity Bottle Winning Price Classification 1 ALLEGIANCE WINES The Artisan Shiraz, Barossa Valley. Screwcap 2015 1 Bottle Passed In Closure. # 2 ALLEGIANCE WINES The Artisan Shiraz, Barossa Valley. Screwcap 2015 1 Bottle Passed In Closure. # 3 ALLEGIANCE WINES The Artisan Shiraz, Barossa Valley. Screwcap 2016 1 Bottle Passed In Closure. # 4 ALLEGIANCE WINES The Artisan Shiraz, Barossa Valley. Screwcap 2016 1 Bottle Passed In Closure. # 5 ALLEGIANCE WINES The Artisan Shiraz, Barossa Valley. Screwcap 2016 1 Bottle Passed In Closure. # 6 ALLEGIANCE WINES Unity Grenache Shiraz Mataro, Barossa Valley. 2015 1 Bottle $41.0000000000 Screwcap Closure. 00000000 7 AMATO VINO Mantra Cabernet, Margaret River. # 2017 1 Bottle Passed In 8 AMATO VINO Mantra Cabernet, Margaret River. # 2017 1 Bottle Passed In 9 AMATO VINO Mantra Cabernet, Margaret River. # 2017 2 Bottle Passed In 10 ANDEVINE WINES Reserve Shiraz, Hunter Valley. Screwcap Closure. 2013 1 Bottle Passed In 11 ANDEVINE WINES Reserve Shiraz, Hunter Valley. Screwcap Closure. 2013 1 Bottle Passed In 12 ANDEVINE WINES Reserve Shiraz, Hunter Valley. Screwcap Closure. 2013 1 Bottle Passed In 13 ANDEVINE WINES Reserve Shiraz, Hunter Valley. Screwcap Closure. 2013 1 Bottle Passed In 14 BIRD ON A WIRE Pinot Noir, Yarra Valley.