Lessons from the Game Cartridge Kevin Christopher Tuesday, March

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Video Game Consoles Introduction the First Generation

A History of Video Game Consoles By Terry Amick – Gerald Long – James Schell – Gregory Shehan Introduction Today video games are a multibillion dollar industry. They are in practically all American households. They are a major driving force in electronic innovation and development. Though, you would hardly guess this from their modest beginning. The first video games were played on mainframe computers in the 1950s through the 1960s (Winter, n.d.). Arcade games would be the first glimpse for the general public of video games. Magnavox would produce the first home video game console featuring the popular arcade game Pong for the 1972 Christmas Season, released as Tele-Games Pong (Ellis, n.d.). The First Generation Magnavox Odyssey Rushed into production the original game did not even have a microprocessor. Games were selected by using toggle switches. At first sales were poor because people mistakenly believed you needed a Magnavox TV to play the game (GameSpy, n.d., para. 11). By 1975 annual sales had reached 300,000 units (Gamester81, 2012). Other manufacturers copied Pong and began producing their own game consoles, which promptly got them sued for copyright infringement (Barton, & Loguidice, n.d.). The Second Generation Atari 2600 Atari released the 2600 in 1977. Although not the first, the Atari 2600 popularized the use of a microprocessor and game cartridges in video game consoles. The original device had an 8-bit 1.19MHz 6507 microprocessor (“The Atari”, n.d.), two joy sticks, a paddle controller, and two game cartridges. Combat and Pac Man were included with the console. In 2007 the Atari 2600 was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame (“National Toy”, n.d.). -

Alive Dead Media 2020: Tracker and Chip Music

Alive Dead Media 2020: Tracker and Chip Music 1st day introduction, Markku Reunanen Pics gracefully provided by Wikimedia Commons Arrangements See MyCourses for more details, but for now: ● Whoami, who’s here? ● Schedule of this week: history, MilkyTracker with Yzi, LSDJ with Miranda Kastemaa, holiday, final concert ● 80% attendance, two tunes for the final concert and a little jingle today ● Questions about the practicalities? History of Home Computer and Game Console Audio ● This is a vast subject: hundreds of different devices and chips starting from the late 1970s ● In the 1990s starts to become increasingly standardized (or boring, if you may :) so we’ll focus on earlier technology ● Not just hardware: how did you compose music with contemporary tools? ● Let’s hear a lot of examples – not using Zoom audio The Home Computer Boom ● At its peak in the 1980s, but started somewhat earlier with Apple II (1977), TRS-80 (1977) and Commodore PET (1977) ● Affordable microprocessors, such as Zilog Z80, MOS 6502 and the Motorola 6800 series ● In the 1980s the market grew rapidly with Commodore VIC-20 (1980) and C-64 (1982), Sinclair ZX Spectrum (1982), MSX compatibles (1983) … and many more! ● From enthusiast gadgets to game machines Enter the 16-bits ● Improving processors: Motorola 68000 series, Intel 8088/8086/80286 ● More colors, more speed, more memory, from tapes to floppies, mouse(!) ● Atari ST (1984), Commodore Amiga (1985), Apple Macintosh (1984) ● IBM PC and compatibles (1981) popular in the US, improving game capability Not Just Computers ● The same technology powered game consoles of the time ● Notable early ones: Fairchild Channel F (1976), Atari VCS aka. -

Chapter 3 Glossary

Video Game Design Foundations ©2014 Chapter 3: Evolution of the Game—Glossary Atari 2600. First commercially successful video game system (1977) for homes; allowed the owner to purchase individual game cartridges. Backward compatibility. Older games can be played on newer game consoles. Balance. Mix of physical, mental, work, and play activities. Behavioral development. Learning how to react to situations. Bit. Computer term for a single binary digit of 0 or 1. Board game. A portable game environment in which players use imagination to engage in mental or strategic competition. Brain-extremity pathways. Nerve connection from the brain to movement points throughout the body. Card games. A series of uniquely printed cards used within set rules of a game. Carpal tunnel syndrome. Condition that causes pain or tingling in the hand resulting from a pinched nerve in the wrist. Chance. Adds interest to a game by allowing different random results each time a game is played. Cocooning. Social phenomenon where people do not interact with their physical environment. Cognitive development. Building of intelligence through learning, remembering, and problem solving. Commercial success. Product that makes enough of a profit to continue producing it. Compact disc, read-only memory (CD-ROM). Provides interchangeable video games on an inexpensive plastic disc; replacement technology for the ROM game cartridges. Compete. To play against an opponent with a goal or victory condition to determine who is the best. Competitive advantage. Benefit to consumers that other companies do not provide. Content descriptors. Part of a rating system; indicates elements in the game that may have triggered a particular rating. -

Openbsd Gaming Resource

OPENBSD GAMING RESOURCE A continually updated resource for playing video games on OpenBSD. Mr. Satterly Updated August 7, 2021 P11U17A3B8 III Title: OpenBSD Gaming Resource Author: Mr. Satterly Publisher: Mr. Satterly Date: Updated August 7, 2021 Copyright: Creative Commons Zero 1.0 Universal Email: [email protected] Website: https://MrSatterly.com/ Contents 1 Introduction1 2 Ways to play the games2 2.1 Base system........................ 2 2.2 Ports/Editors........................ 3 2.3 Ports/Emulators...................... 3 Arcade emulation..................... 4 Computer emulation................... 4 Game console emulation................. 4 Operating system emulation .............. 7 2.4 Ports/Games........................ 8 Game engines....................... 8 Interactive fiction..................... 9 2.5 Ports/Math......................... 10 2.6 Ports/Net.......................... 10 2.7 Ports/Shells ........................ 12 2.8 Ports/WWW ........................ 12 3 Notable games 14 3.1 Free games ........................ 14 A-I.............................. 14 J-R.............................. 22 S-Z.............................. 26 3.2 Non-free games...................... 31 4 Getting the games 33 4.1 Games............................ 33 5 Former ways to play games 37 6 What next? 38 Appendices 39 A Clones, models, and variants 39 Index 51 IV 1 Introduction I use this document to help organize my thoughts, files, and links on how to play games on OpenBSD. It helps me to remember what I have gone through while finding new games. The biggest reason to read or at least skim this document is because how can you search for something you do not know exists? I will show you ways to play games, what free and non-free games are available, and give links to help you get started on downloading them. -

New Joysticks Available for Your Atari 2600

May Your Holiday Season Be a Classic One Classic Gamer Magazine Classic Gamer Magazine December 2000 3 The Xonox List 27 Teach Your Children Well 28 Games of Blame 29 Mit’s Revenge 31 The Odyssey Challenger Series 34 Interview With Bob Rosha 38 Atari Arcade Hits Review 41 Jaguar: Straight From the Cat’s 43 Mouth 6 Homebrew Review 44 24 Dear Santa 46 CGM Online Reset 5 22 So, what’s Happening with CGM Newswire 6 our website? Upcoming Releases 8 In the coming months we’ll Book Review: The First Quarter 9 be expanding our web pres- Classic Ad: “Fonz” from 1976 10 ence with more articles, games and classic gaming merchan- Lost Arcade Classic: Guzzler 11 dise. Right now we’re even The Games We Love to Hate 12 shilling Classic Gamer Maga- zine merchandise such as The X-Games 14 t-shirts and coffee mugs. Are These Games Unplayable? 16 So be sure to check online with us for all the latest and My Favorite Hedgehog 18 greatest in classic gaming news Ode to Arcade Art 20 and fun. Roland’s Rat Race for the C-64 22 www.classicgamer.com Survival Island 24 Head ‘em Off at the Past 48 Classic Ad: “K.C. Munchkin” 1982 49 My .025 50 Make it So, Mr. Borf! Dragon’s Lair 52 and Space Ace DVD Review How I Tapped Out on Tapper 54 Classifieds 55 Poetry Contest Winners 55 CVG 101: What I Learned Over 56 Summer Vacation Atari’s Misplays and Bogey’s 58 46 Deep Thaw 62 38 Classic Gamer Magazine December 2000 4 “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to Issue 5 repeat it” - George Santayana December 2000 Editor-in-Chief “Unfortunately, those of us who do remember the past are Chris Cavanaugh condemned to repeat it with them." - unaccredited [email protected] Managing Editor -Box, Dreamcast, Play- and the X-Box? Well, much to Sarah Thomas [email protected] Station, PlayStation 2, the chagrin of Microsoft bashers Gamecube, Nintendo 64, everywhere, there is one rule of Contributing Writers Indrema, Nuon, Game business that should never be X Mark Androvich Boy Advance, and the home forgotten: Never bet against Bill. -

Sega Genesis Manual

January 22, 2009 Sega Technical Overview 1.00 Page 1 GENESIS Technical Overview CONFIDENTIAL PROPERTY OF SEGA Look forward to more Tech notes: Super Nintendo Jaguar Edited by Nemesis – corrupted images repaired January 22, 2009 Sega Technical Overview 1.00 Page 2 GENESIS: 68000 @8 MHz • main CPU • 1 MByte (8 Mbit) ROM Area • 64 KByte RAM Area VDP (Video Display Processor) • dedicated video display processor - controls playfield & sprites - capable of DMA - Horizontal & Vertical interrupts • 64 KBytes of dedicated VRAM (Video Ram) • 64 x 9-bits of CRAM (Color RAM) Z80 @4 MHz • controls PSG (Programmable Sound Generator) & FM Chips • 8 KBytes of dedicated Sound Ram VIDEO: • NOTE: Playfield and Sprites are character-based • Display Area (visual) - 40 chars wide x 28 chars high • each char is 8 x 8 pixels • pixel resolution = 320 x 224 - 3 Planes • 2 scrolling playfields • 1 sprite plane • definable priorities between planes - Playfields: • 6 different sizes • 1 playfield can have a "fixed" window • playfield map - each char position takes 2 Bytes, that includes: • char name (10 bits); points to char definition • horizontal flip • vertical flip • color palette (2 bits); index into CRAM • priority January 22, 2009 Sega Technical Overview 1.00 Page 3 • scrolling: - 1 pixel scrolling resolution - horizontal: • whole playfield as unit • each character line • each scan line - vertical: • whole playfield as unit • 2 char wide columns - Sprites: • 1 x 1 char up to 4 x 4 chars • up to 80 sprites can be defined • up to 20 sprites displayed on a scan -

Classic Home Video Games, 1972-1984: a Complete Reference Guide, 2012, 316 Pages, Brett Weiss, 0786487550, 9780786487554, Mcfarland, 2012

Classic Home Video Games, 1972-1984: A Complete Reference Guide, 2012, 316 pages, Brett Weiss, 0786487550, 9780786487554, McFarland, 2012 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1Xr2Udg http://www.abebooks.com/servlet/SearchResults?sts=t&tn=Classic+Home+Video+Games%2C+1972-1984%3A+A+Complete+Reference+Guide&x=51&y=16 В В This reference work provides a comprehensive guide to popular and obscure video games of the 1970s and early 1980s, covering virtually every official United States release for programmable home game consoles of the pre-Nintendo NES era. Included are the following systems: Adventure Vision, APF MP1000, Arcadia 2001, Astrocade, Atari 2600, Atari 5200, Atari 7800, ColecoVision, Fairchild Channel F, Intellivision, Microvision, Odyssey, Odyssey2, RCA Studio II, Telstar Arcade, and Vectrex.В В Organized alphabetically by console brand, each chapter includes a history and description of the game system, followed by substantive entries for every game released for that console, regardless of when the game was produced. Each video game entry includes publisher/developer information and the release year, along with a detailed description and, frequently, the author's critique. An appendix lists "homebrew" titles that have been created by fans and amateur programmers and are available for download or purchase. Includes glossary, bibliography and index. DOWNLOAD http://goo.gl/RpYVf http://www.fishpond.co.nz/Books/Classic-Home-Video-Games-1972-1984-A-Complete-Reference-Guide http://bit.ly/1oMMb2z The Official Xbox Magazine, Issues 53-55 , , 2006, Video games, . Screenshot Reference - CX2600 edition - vol. 2, # - e , , , , . Phoenix The Fall & Rise of Videogames, Leonard Herman, Keith Feinstein, Sep 1, 1997, Games, 312 pages. -

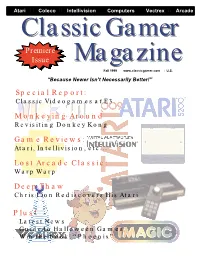

Premiere Issue Monkeying Around Game Reviews: Special Report

Atari Coleco Intellivision Computers Vectrex Arcade ClassicClassic GamerGamer Premiere Issue MagazineMagazine Fall 1999 www.classicgamer.com U.S. “Because Newer Isn’t Necessarily Better!” Special Report: Classic Videogames at E3 Monkeying Around Revisiting Donkey Kong Game Reviews: Atari, Intellivision, etc... Lost Arcade Classic: Warp Warp Deep Thaw Chris Lion Rediscovers His Atari Plus! · Latest News · Guide to Halloween Games · Win the book, “Phoenix” “As long as you enjoy the system you own and the software made for it, there’s no reason to mothball your equipment just because its manufacturer’s stock dropped.” - Arnie Katz, Editor of Electronic Games Magazine, 1984 Classic Gamer Magazine Fall 1999 3 Volume 1, Version 1.2 Fall 1999 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Chris Cavanaugh - [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Sarah Thomas - [email protected] STAFF WRITERS Kyle Snyder- [email protected] Reset! 5 Chris Lion - [email protected] Patrick Wong - [email protected] Raves ‘N Rants — Letters from our readers 6 Darryl Guenther - [email protected] Mike Genova - [email protected] Classic Gamer Newswire — All the latest news 8 Damien Quicksilver [email protected] Frank Traut - [email protected] Lee Seitz - [email protected] Book Bytes - Joystick Nation 12 LAYOUT/DESIGN Classic Advertisement — Arcadia Supercharger 14 Chris Cavanaugh PHOTO CREDITS Atari 5200 15 Sarah Thomas - Staff Photographer Pong Machine scan (page 3) courtesy The “New” Classic Gamer — Opinion Column 16 Sean Kelly - Digital Press CD-ROM BIRA BIRA Photos courtesy Robert Batina Lost Arcade Classics — ”Warp Warp” 17 CONTACT INFORMATION Classic Gamer Magazine Focus on Intellivision Cartridge Reviews 18 7770 Regents Road #113-293 San Diego, Ca 92122 Doin’ The Donkey Kong — A closer look at our 20 e-mail: [email protected] on the web: favorite monkey http://www.classicgamer.com Atari 2600 Cartridge Reviews 23 SPECIAL THANKS To Sarah. -

Examining the Dynamics of the US Video Game Console Market

Can Nintendo Get its Crown Back? Examining the Dynamics of the U.S. Video Game Console Market by Samuel W. Chow B.S. Electrical Engineering, Kettering University, 1997 A.L.M. Extension Studies in Information Technology, Harvard University, 2004 Submitted to the System Design and Management Program, the Technology and Policy Program, and the Engineering Systems Division on May 11, 2007 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science in Engineering and Management and Master of Science in Technology and Policy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2007 C 2007 Samuel W. Chow. All rights reserved The author hereby grants to NIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now know and hereafter created. Signature of Author Samuel W. Chow System Design and Management Program, and Technology and Policy Program May 11, 2007 Certified by James M. Utterback David J. cGrath jr 9) Professor of Management and Innovation I -'hs Supervisor Accepted by Pat Hale Senior Lecturer in Engineering Systems - Director, System Design and Management Program Accepted by Dava J. Newman OF TEOHNOLoGY Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Engineering Systems Director, Technology and Policy Program FEB 1 E2008 ARCHNOE LIBRARIES Can Nintendo Get its Crown Back? Examining the Dynamics of the U.S. Video Game Console Market by Samuel W. Chow Submitted to the System Design and Management Program, the Technology and Policy Program, and the Engineering Systems Division on May 11, 2007 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science in Engineering and Management and Master of Science in Technology and Policy Abstract Several generations of video game consoles have competed in the market since 1972. -

Keeping the Game Alive: Evaluating Strategies for the Preservation of Console Video Games

64 Keeping the Game Alive The International Journal of Digital Curation Issue 1, Volume 5 | 2010 Keeping the Game Alive: Evaluating Strategies for the Preservation of Console Video Games Mark Guttenbrunner, Christoph Becker, Andreas Rauber, Vienna University of Technology Abstract Interactive fiction and video games are part of our cultural heritage. As original systems cease to work because of hardware and media failures, methods to preserve obsolete video games for future generations have to be developed. The public interest in early video games is high, as exhibitions, regular magazines on the topic and newspaper articles demonstrate. Moreover, games considered to be classic are rereleased for new generations of gaming hardware. However, with the rapid development of new computer systems, the way games look and are played changes constantly. When trying to preserve console video games one faces problems of classified development documentation, legal aspects and extracting the contents from original media like cartridges with special hardware. Furthermore, special controllers and non-digital items are used to extend the gaming experience making it difficult to preserve the look and feel of console video games. This paper discusses strategies for the digital preservation of console video games. After a short overview of console video game systems, there follows an introduction to digital preservation and related work in common strategies for digital preservation and preserving interactive art. Then different preservation strategies are described with a specific focus on emulation. Finally a case study on console video game preservation is shown which uses the Planets preservation planning approach for evaluating preservation strategies in a documented decision-making process. -

Arcade Machine Reloaded Build Documentation

Arcade Machine Build Documentation v5.0 Revision Date: 2011-02-03 Author: Jeremy Riley (AKA Zorro) http://www.flashingblade.net Table of Contents Arcade Machine Reloaded Build Documentation....................................................................5 Introduction.................................................................................................................................5 Windows & MAMEWah Build..............................................................................................................5 MAMEWah Quickstart................................................................................................... 6 Hardware Notes:....................................................................................................... 11 Arcade Monitor Settings.................................................................................................................11 Arcade Keys...............................................................................................................................12 Tuning MAMEWah...................................................................................................... 13 MAME Resolutions.........................................................................................................................13 Using Custom Layouts....................................................................................................................13 Artwork.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................13 -

Supreme GPI Is the Most Advance Custom Build for the Retroflag GPI Case (Pi Zero and Zero W)

Supreme GPI is the most advance custom build for the RetroFlag GPI case (Pi zero and Zero W). Our goal is always to make the very best base build for every type of user. We only use the most updated emulators, scripts, front end advancements and tweaks from the pi community. Supreme GPI have : -The Biggest systems support. -The Biggest script library. -Most advance tweaks from the community. 1 1/ Features -5 ES themes rework to fit GPI screen perfectly. -Gpi screen case patch. -Safe shutdown. -No Boot logo and text. -Background music. -Mono audio output. -Fast boot. -Many Script added from supreme unified and community : *Audiotools, *Controllertools, *Emulationtools, *Retropietools, *Visualtools, *Wifi-Bluetooth. -Some script created for GPI case and pi zero(W) only: *Audio output, *Overclock, *Wifi and BT toogle, *Wifi restore, *Fix my build Script. -Online build updater (download, change or upgrade your Supreme GPI build in one click). -Control updater menu. -Clean Emulationstation and options menu. -Standalone emulator (PSX, GBA, SNES, ARCADE, SCUMMVM…) for better performance (no input tweak). -Video loading screen. -PSX-Rearmed crash “fixed”. -All package updated to last commit. -News emulators and systems added. 2 -New tweaks, build Features, options and more… 2/ How to install A) Burn your SD card -Format your sd card with sdformater (format type full). -Burn the ".img" file with Win32DiskImager (WIN) or Appbaker (MACOS). First boot can be longuer (the devise will boot and reboot). Wait until you are on Emulationstation home screen. B/ Wifi setup (pi zero W) -Open the wpa_supplicant.conf file with notepad (or notepad++).