"Creating Dissonance for the Visitor": the Heart of the Liberty Bell Controversy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008 Annual Report

5 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE FEATURED ARTICLES AND THE 2008 ANNUAL REPORT Benjamin Franklin’s Shoe PAGE 4 A Road Rich with Milestones PAGE 10 Today and Tomorrow: 2008 Annual Report PAGE 16 2008 Financials PAGE 22 FEATUREMAILBOX ONE 2 NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER 5 Years of Excellence LETTER FROM THE EDITORS Dear Friends: Exceptional. That is the only word that can fully describe the remarkable strides the National Constitution Center has made in the past five years. Since opening its doors on July 4, 2003, it has developed into one of the most esteemed institutions for the ongoing study, discussion and celebration of the United States’ most cherished document. We’re pleased to present a celebration of the Center’s first five years and the 2008 Annual Report. In the following pages you will read about the Center’s earliest days and the milestones it has experienced. You will learn about the moving exhibitions it has developed and presented over the years. You will look back at the many robust public conversations led by national figures that have occurred on site, and you will be introduced to a new and innovative international initiative destined to carry the Center boldly into the future. It has been a true pleasure to work for this venerable institution, informing and inspiring We the People. We both look forward to witnessing the Center’s future achievements and we are honored that the next chapter of this story will be written by the Center’s new Chairman, President Bill Clinton. Sincerely, President George H. W. Bush Joseph M. -

Carillon News No. 80

No. 80 NovemberCarillon 2008 News www.gcna.org Newsletter of the Guild of Carillonneurs in North America Berkeley Opens Golden Arms to Features 2008 GCNA Congress GCNA Congress by Sue Bergren and Jenny King at Berkeley . 1 he University of California at TBerkeley, well known for its New Carillonneur distinguished faculty and academic Members . 4 programs, hosted the GCNA’s 66th Congress from June 10 through WCF Congress in June 13. As in 1988 and 1998, the 2008 Congress was held jointly Groningen . .. 5 with the Berkeley Carillon Festival, an event held every five years to Search for Improving honor the Class of 1928. Hosted by Carillons: Key Fall University Carillonist Jeff Davis, vs. Clapper Stroke . 7 the congress focused on the North American carillon and its music. The Class of 1928 Carillon Belgium, began as a chime of 12 Taylor bells. Summer 2008 . 8 In 1978, the original chime was enlarged to a 48-bell carillon by a Plus gift of 36 Paccard bells from the Class of 1928. In 1982, Evelyn and Jerry Chambers provided an additional gift to enlarge the instrument to a grand carillon of Calendar . 3 61 bells. The University of California at Berkeley, with Sather Tower and The Class of 1928 Installations, Carillon, provided a magnificent setting and instrument for the GCNA congress and Renovations, Berkeley festival. More than 100 participants gathered for artist and advancement recitals, Dedications . 11 general business meetings and scholarly presentations, opportunities to review and pur- chase music, and lots of food, drink, and camaraderie. Many participants were able to walk Overtones from their hotels to the campus, stopping on the way for a favorite cup of coffee. -

The Liberty Bell: a Symbol for “We the People” Teacher Guide with Lesson Plans

Independence National Historical National Park Service ParkPennsylvania U.S. Department of the Interior The Liberty Bell: A Symbol for “We the People” Teacher Guide with Lesson Plans Grades K – 12 A curriculum-based education program created by the Independence Park Institute at Independence National Historical Park www.independenceparkinstitute.com 1 The Liberty Bell: A Symbol for “We the People” This education program was made possible through a partnership between Independence National Historical Park and Eastern National, and through the generous support of the William Penn Foundation. Contributors Sandy Avender, Our Lady of Lords, 5th-8th grade Kathleen Bowski, St. Michael Archangel, 4th grade Kate Bradbury, Rydal (East) Elementary, 3rd grade Amy Cohen, J.R. Masterman, 7th & 10th grade Kim General, Toms River High School North, 9th-12th grade Joyce Huff, Enfield Elementary School, K-1st grade and Library Coach Barbara Jakubowski, Strawbridge School, PreK-3rd grade Joyce Maher, Bellmawr Park, 4th grade Leslie Matthews, Overbrook Education Center, 3rd grade Jennifer Migliaccio, Edison School, 5th grade JoAnne Osborn, St. Christopher, 1st-3rd grade Elaine Phipps, Linden Elementary School, 4th-6th grade Monica Quinlan-Dulude, West Deptford Middle School, 8th grade Jacqueline Schneck, General Washington Headquarts at Moland House, K-12th grade Donna Scott-Brown, Chester High School, 9th-12th grade Sandra Williams, George Brower PS 289, 1st-5th grade Judith Wrightson, St. Christopher, 3rd grade Editors Jill Beccaris-Pescatore, Green Woods -

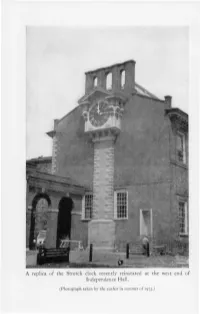

A Replica of the Stretch Clock Recently Reinstated at the West End of Independence Hall

A replica of the Stretch clock recently reinstated at the west end of Independence Hall. (Photograph taken by the author in summer of 197J.) THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Stretch Qlock and its "Bell at the State House URING the spring of 1973, workmen completed the construc- tion of a replica of a large clock dial and masonry clock D case at the west end of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the original of which had been installed there in 1753 by a local clockmaker, Thomas Stretch. That equipment, which resembled a giant grandfather's clock, had been removed in about 1830, with no other subsequent effort having been made to reconstruct it. It therefore seems an opportune time to assemble the scattered in- formation regarding the history of that clock and its bell and to present their stories. The acquisition of the original clock and bell by the Pennsylvania colonial Assembly is closely related to the acquisition of the Liberty Bell. Because of this, most historians have tended to focus their writings on that more famous bell, and to pay but little attention to the hard-working, more durable, and equally large clock bell. They have also had a tendency either to claim or imply that the Liberty Bell and the clock bell had been procured in connection with a plan to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary, or "Jubilee Year," of the granting of the Charter of Privileges to the colony by William Penn. But, with one exception, nothing has been found among the surviving records which would support such a contention. -

About the Carillon

ABOUT THE CARILLON The carillon at Concordia Seminary is one of only 170 such instruments in North America. The 49 bells have been played atop Luther Tower since 1971, and are dedicated to all pastors who have served The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod (LCMS). It is housed in Luther Tower, the 120- foot structure designed by architect Charles Klauder and dedicated in 1966. CONCORDIA SEMINARY, ST. LOUIS CARILLON CONCERT JUNE 26, 2018 7 P.M. KAREL KELDERMANS CARILLONNEUR Concordia Seminary 801 Seminary Place St. Louis, MO 63105 www.csl.edu 314-505-7000 PROGRAM BIOGRAPHY 1. Fugue Matthias van den Gheyn (1721-85) KAREL KELDERMANS is one of the pre-eminent carillonneurs in North arr. Karel Keldermans America. He has been the carillonneur for Concordia Seminary, St. Louis since 2000. He retired in 2012 from the position of full-time carillonneur 2. Leyenda Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909) for the Springfield Park District in Springfield, Ill., where he also served as arr. Bert Gerken the director of the renowned International Carillon Festival for 36 years. 3. Suite Archaique Geo Clement (1902-69) He has given carillon concerts around the world for the past 40 years. He has released six solo carillon CDs and one of carillon and guitar duets Rigaudon, Pavane, Menuet with Belgian guitarist Wim Brioen. 4. Allegro Reijnold Popma van Oevering (1692-1781) For 12 years, along with his wife, Linda, he was co-owner of American arr. Karel Keldermans Carillon Music Editions, the largest publisher of new music for the carillon in the world. He was president of the Guild of Carillonneurs in North 5. -

National Register of Historic Places

Form No. ^0-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Independence National Historical Park AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 313 Walnut Street CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT t Philadelphia __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE PA 19106 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE 2LMUSEUM -BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —^COMMERCIAL 2LPARK .STRUCTURE 2EBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —XEDUCATIONAL ^.PRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS -OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED ^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: REGIONAL HEADQUABIER REGION STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE PHILA.,PA 19106 VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, ____________PhiladelphiaREGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. _, . - , - , Ctffv.^ Hall- - STREET & NUMBER n^ MayTftat" CITY. TOWN STATE Philadelphia, PA 19107 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL CITY. TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 2S.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD h^b Jk* SANWJIt's ALTERED _MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED Description: In June 1948, with passage of Public Law 795, Independence National Historical Park was established to preserve certain historic resources "of outstanding national significance associated with the American Revolution and the founding and growth of the United States." The Park's 39.53 acres of urban property lie in Philadelphia, the fourth largest city in the country. All but .73 acres of the park lie in downtown Phila-* delphia, within or near the Society Hill and Old City Historic Districts (National Register entries as of June 23, 1971, and May 5, 1972, respectively). -

SAVED by the BELL ! the RESURRECTION of the WHITECHAPEL BELL FOUNDRY a Proposal by Factum Foundation & the United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust

SAVED BY THE BELL ! THE RESURRECTION OF THE WHITECHAPEL BELL FOUNDRY a proposal by Factum Foundation & The United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust Prepared by Skene Catling de la Peña June 2018 Robeson House, 10a Newton Road, London W2 5LS Plaques on the wall above the old blacksmith’s shop, honouring the lives of foundry workers over the centuries. Their bells still ring out through London. A final board now reads, “Whitechapel Bell Foundry, 1570-2017”. Memorial plaques in the Bell Foundry workshop honouring former workers. Cover: Whitechapel Bell Foundry Courtyard, 2016. Photograph by John Claridge. Back Cover: Chains in the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, 2016. Photograph by John Claridge. CONTENTS Overview – Executive Summary 5 Introduction 7 1 A Brief History of the Bell Foundry in Whitechapel 9 2 The Whitechapel Bell Foundry – Summary of the Situation 11 3 The Partners: UKHBPT and Factum Foundation 12 3 . 1 The United Kingdom Historic Building Preservation Trust (UKHBPT) 12 3 . 2 Factum Foundation 13 4 A 21st Century Bell Foundry 15 4 .1 Scanning and Input Methods 19 4 . 2 Output Methods 19 4 . 3 Statements by Participating Foundrymen 21 4 . 3 . 1 Nigel Taylor of WBF – The Future of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry 21 4 . 3 . 2 . Andrew Lacey – Centre for the Study of Historical Casting Techniques 23 4 . 4 Digital Restoration 25 4 . 5 Archive for Campanology 25 4 . 6 Projects for the Whitechapel Bell Foundry 27 5 Architectural Approach 28 5 .1 Architectural Approach to the Resurrection of the Bell Foundry in Whitechapel – Introduction 28 5 . 2 Architects – Practice Profiles: 29 Skene Catling de la Peña 29 Purcell Architects 30 5 . -

Bells – General

5. BELLS - GENERAL Acc. Author Title Date Publisher and other details No. 541 Adams, Alice Thérèse Church Bells 1930 Catholic Truth Society of Ireland, Dublin 28pp 2419 Appleby, Robert Time for a change? Ring Church Bells for Fun and Friendship 1997 Treetop Books , Bradford 27pp ISBN 1-898476-01-2 1863 Anon Baptism of Bells, The 1855 The Bulwark 2pp Extracted from the issue of 1 Oct. 1855, pp106-7 (25) 1863 Anon German Campanology. English translation from Organ für Christliche Kunst 1867 The Ecclesiologist 6pp Pages 363-368 (27) 92 Anon Church Bells: their Uses, their Romance and their History 1903 Sir W C Leng and Co Ltd, Sheffield 51pp Reprinted from the Sheffield Telegraph 1776 Anon Bells, The 1976, Jul The Seal 9pp Offprint of article in the house journal of the Walsall Lithographic Co Ltd Also photocopy of same 1868 Anon A History of Bells, and description of their manufacture, as practised at the n.d. (post Cassell, Petter and Galpin, London 24pp, illustrated Reprinted from Bell Foundry, Whitechapel 1865) Cassell’s Magazine of Art (1854) Revised up to the present date 805 B B C Radio for Schools Discovery 1973, Aut Pupil’s Pamphlet 36pp 806 B B C Radio for Schools Ring Out Wild Bells 1973, Aut Teacher’s Notes for ‘Discovery’ Autumn 1973 (Illustrated script of Broadcast) 18pp 87 Beamont, W A Chapter on Bells and Inscriptions upon some of them 1888 Percival Pearse, Warrington 43pp 3076 Beckett, Sir Edmund Bart. A rudimentary treatise on clocks and watches and bells 1883 Crosby, Lockwood & Co, London 7th edition xiii + 400pp (Lord Grimthorpe) See also under Denison and Grimthorpe for other editions 1863 Berkeley, Revd Sackville H Church Bells: their true worth and true influence. -

Campaign Fact Book Former Whitechapel Bell Foundry Site Whitechapel, London

Campaign Fact Book Former Whitechapel Bell Foundry Site Whitechapel, London Compiled January 2020 Whitechapel Bell Foundry: a matter of national importance This fact book has been compiled to capture the breadth of the campaign to save the site of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, which is currently threatened by a proposal for conversion into a boutique hotel. Re-Form Heritage; Factum Foundation; numerous community, heritage and bellringing organisations; and thousands of individuals have contributed to and driven this campaign, which is working to: reinstate modern and sustainable foundry activity on the site preserve and record heritage skills integrate new technologies with traditional foundry techniques maintain and build pride in Whitechapel’s bell founding heritage The site of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry is Britain’s oldest single-purpose industrial building where for generations bells such as Big Ben, the Liberty Bell, Bow Bells and many of the world’s great bells were made. Bells made in Whitechapel have become the voices of nations, marking the world’s celebrations and sorrows and representing principles of emancipation, freedom of expression and justice. As such these buildings and the uses that have for centuries gone on within them represent some of the most important intangible cultural heritage and are therefore of international significance. Once the use of the site as a foundry has gone it has gone forever. The potential impact of this loss has led to considerable concern and opposition being expressed on an unprecedented scale within the local area, nationally and, indeed, internationally. People from across the local community, London and the world have voiced their strong opposition to the developer’s plans and to the hotel use and wish for the foundry use to be retained. -

Campanologist Chronicles

CAMPANOLOGIST CHRONICLES This a tremendous history of the bells in St Andrew’s Parish Church. The oldest dates from the time of Queen Elizabeth, in 1595 for bells 5 and 6, 1654 for the 4th, 1738 for the 3rd and 7th and 1759 for the 10¾cwt tenor. In all the bells weigh 43cwt, just over 2 tons. Following the village’s centuries old tradition of ringing church bells, the current band of ringers has been making steady progress. Unfortunately, over the years the bells have become increasingly difficult to ring, which makes teaching new recruits difficult and produces poor quality ringing. As with all mechanical devices, bells require periodic maintenance, and it is usual for bells and their fittings to require major attention every 50 years or so. The last major work to St Andrew’s bells was carried out seventy years ago in 1947, so now is the time for the current generation to take action, so that the bells can be enjoyed by future generations. Recent inspections from three bell hanging firms have highlighted the poor installation and condition of the fittings, most of which date from the 19th century and appear not to have been renewed back in 1947, during the period of austerity after the war when funds would have been scarce. At that time the eight-bell frame was installed and the two treble bells, as part of a war memorial. Significantly this was the last timber frame to be supplied by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. Sadly, the foundry, the oldest in the world and Britain's oldest manufacturing company, which made Big Ben and Liberty Bell, closed earlier this year. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory

Form No. ^0-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Independence National Historical Park AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 313 Walnut Street CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT t Philadelphia __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE PA 19106 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE 2LMUSEUM -BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —^COMMERCIAL 2LPARK .STRUCTURE 2EBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —XEDUCATIONAL ^.PRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS -OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED ^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: REGIONAL HEADQUABIER REGION STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE PHILA.,PA 19106 VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, ____________PhiladelphiaREGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. _, . - , - , Ctffv.^ Hall- - STREET & NUMBER n^ MayTftat" CITY. TOWN STATE Philadelphia, PA 19107 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL CITY. TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 2S.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD h^b Jk* SANWJIt's ALTERED _MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED Description: In June 1948, with passage of Public Law 795, Independence National Historical Park was established to preserve certain historic resources "of outstanding national significance associated with the American Revolution and the founding and growth of the United States." The Park's 39.53 acres of urban property lie in Philadelphia, the fourth largest city in the country. All but .73 acres of the park lie in downtown Phila-* delphia, within or near the Society Hill and Old City Historic Districts (National Register entries as of June 23, 1971, and May 5, 1972, respectively). -

The Liberty Bell by Katie Clark

Name : The Liberty Bell by Katie Clark Have you heard of the Liberty Bell? It stands for freedom. It was used by America’s founders. The bell was made over 200 years ago. It was made from metals like tin and copper. It was made by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in London. The bell cracked the !rst time it was rung. It has cracked many times since then. The bell is no longer rung. This is to protect it. The last time it was rung was in 1846. That was in honor of George Washington’s birthday. The bell is very big. It weighs over one ton, or two thousand pounds. It is three feet tall. Over one million people visit the bell each year. It is at a place called Liberty Bell Hall. It still hangs from its very !rst yoke. A yoke is the wood that holds the bell. A picture of the bell has been printed on coins and postage stamps. It is very special to see this piece of history. Printable Worksheets @ www.mathworksheets4kids.com Name : The Liberty Bell 1) The bell is made from metals like...... a) gold and silver b) bronze and silver c) silver and copper d) tin and copper 2) What does the liberty bell stand for? 3) The bell was manufactured by the . 4) Where can you !nd the picture of the bell? 5) Describe the bell. Printable Worksheets @ www.mathworksheets4kids.com Name : Answer key The Liberty Bell 1) The bell is made from metals like...... a) gold and silver b) bronze and silver c) silver and copper d) tin and copper 2) What does the liberty bell stand for? The Liberty Bell is a symbol of American independence.