MATH CLUB: IDENTIFICATION SPACE 1. M Obius Strip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note on 6-Regular Graphs on the Klein Bottle Michiko Kasai [email protected]

Theory and Applications of Graphs Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 5 2017 Note On 6-regular Graphs On The Klein Bottle Michiko Kasai [email protected] Naoki Matsumoto Seikei University, [email protected] Atsuhiro Nakamoto Yokohama National University, [email protected] Takayuki Nozawa [email protected] Hiroki Seno [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/tag Part of the Discrete Mathematics and Combinatorics Commons Recommended Citation Kasai, Michiko; Matsumoto, Naoki; Nakamoto, Atsuhiro; Nozawa, Takayuki; Seno, Hiroki; and Takiguchi, Yosuke (2017) "Note On 6-regular Graphs On The Klein Bottle," Theory and Applications of Graphs: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. DOI: 10.20429/tag.2017.040105 Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/tag/vol4/iss1/5 This article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theory and Applications of Graphs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Note On 6-regular Graphs On The Klein Bottle Authors Michiko Kasai, Naoki Matsumoto, Atsuhiro Nakamoto, Takayuki Nozawa, Hiroki Seno, and Yosuke Takiguchi This article is available in Theory and Applications of Graphs: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/tag/vol4/iss1/5 Kasai et al.: 6-regular graphs on the Klein bottle Abstract Altshuler [1] classified 6-regular graphs on the torus, but Thomassen [11] and Negami [7] gave different classifications for 6-regular graphs on the Klein bottle. In this note, we unify those two classifications, pointing out their difference and similarity. -

Hydraulic Cylinder Replacement for Cylinders with 3/8” Hydraulic Hose Instructions

HYDRAULIC CYLINDER REPLACEMENT FOR CYLINDERS WITH 3/8” HYDRAULIC HOSE INSTRUCTIONS INSTALLATION TOOLS: INCLUDED HARDWARE: • Knife or Scizzors A. (1) Hydraulic Cylinder • 5/8” Wrench B. (1) Zip-Tie • 1/2” Wrench • 1/2” Socket & Ratchet IMPORTANT: Pressure MUST be relieved from hydraulic system before proceeding. PRESSURE RELIEF STEP 1: Lower the Power-Pole Anchor® down so the Everflex™ spike is touching the ground. WARNING: Do not touch spike with bare hands. STEP 2: Manually push the anchor into closed position, relieving pressure. Manually lower anchor back to the ground. REMOVAL STEP 1: Remove the Cylinder Bottom from the Upper U-Channel using a 1/2” socket & wrench. FIG 1 or 2 NOTE: For Blade models, push bottom of cylinder up into U-Channel and slide it forward past the Ram Spacers to remove it. Upper U-Channel Upper U-Channel Cylinder Bottom 1/2” Tools 1/2” Tools Ram 1/2” Tools Spacers Cylinder Bottom If Ram-Spacers fall out Older models have (1) long & (1) during removal, push short Ram Spacer. Ram Spacers 1/2” Tools bushings in to hold MUST be installed on the same side Figure 1 Figure 2 them in place. they were removed. Blade Models Pro/Spn Models Need help? Contact our Customer Service Team at 1 + 813.689.9932 Option 2 HYDRAULIC CYLINDER REPLACEMENT FOR CYLINDERS WITH 3/8” HYDRAULIC HOSE INSTRUCTIONS STEP 2: Remove the Cylinder Top from the Lower U-Channel using a 1/2” socket & wrench. FIG 3 or 4 Lower U-Channel Lower U-Channel 1/2” Tools 1/2” Tools Cylinder Top Cylinder Top Figure 3 Figure 4 Blade Models Pro/SPN Models STEP 3: Disconnect the UP Hose from the Hydraulic Cylinder Fitting by holding the 1/2” Wrench 5/8” Wrench Cylinder Fitting Base with a 1/2” wrench and turning the Hydraulic Hose Fitting Cylinder Fitting counter-clockwise with a 5/8” wrench. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

Volumes of Prisms and Cylinders 625

11-4 11-4 Volumes of Prisms and 11-4 Cylinders 1. Plan Objectives What You’ll Learn Check Skills You’ll Need GO for Help Lessons 1-9 and 10-1 1 To find the volume of a prism 2 To find the volume of • To find the volume of a Find the area of each figure. For answers that are not whole numbers, round to prism a cylinder the nearest tenth. • To find the volume of a 2 Examples cylinder 1. a square with side length 7 cm 49 cm 1 Finding Volume of a 2. a circle with diameter 15 in. 176.7 in.2 . And Why Rectangular Prism 3. a circle with radius 10 mm 314.2 mm2 2 Finding Volume of a To estimate the volume of a 4. a rectangle with length 3 ft and width 1 ft 3 ft2 Triangular Prism backpack, as in Example 4 2 3 Finding Volume of a Cylinder 5. a rectangle with base 14 in. and height 11 in. 154 in. 4 Finding Volume of a 6. a triangle with base 11 cm and height 5 cm 27.5 cm2 Composite Figure 7. an equilateral triangle that is 8 in. on each side 27.7 in.2 New Vocabulary • volume • composite space figure Math Background Integral calculus considers the area under a curve, which leads to computation of volumes of 1 Finding Volume of a Prism solids of revolution. Cavalieri’s Principle is a forerunner of ideas formalized by Newton and Leibniz in calculus. Hands-On Activity: Finding Volume Explore the volume of a prism with unit cubes. -

Equivelar Octahedron of Genus 3 in 3-Space

Equivelar octahedron of genus 3 in 3-space Ruslan Mizhaev ([email protected]) Apr. 2020 ABSTRACT . Building up a toroidal polyhedron of genus 3, consisting of 8 nine-sided faces, is given. From the point of view of topology, a polyhedron can be considered as an embedding of a cubic graph with 24 vertices and 36 edges in a surface of genus 3. This polyhedron is a contender for the maximal genus among octahedrons in 3-space. 1. Introduction This solution can be attributed to the problem of determining the maximal genus of polyhedra with the number of faces - . As is known, at least 7 faces are required for a polyhedron of genus = 1 . For cases ≥ 8 , there are currently few examples. If all faces of the toroidal polyhedron are – gons and all vertices are q-valence ( ≥ 3), such polyhedral are called either locally regular or simply equivelar [1]. The characteristics of polyhedra are abbreviated as , ; [1]. 2. Polyhedron {9, 3; 3} V1. The paper considers building up a polyhedron 9, 3; 3 in 3-space. The faces of a polyhedron are non- convex flat 9-gons without self-intersections. The polyhedron is symmetric when rotated through 1804 around the axis (Fig. 3). One of the features of this polyhedron is that any face has two pairs with which it borders two edges. The polyhedron also has a ratio of angles and faces - = − 1. To describe polyhedra with similar characteristics ( = − 1) we use the Euler formula − + = = 2 − 2, where is the Euler characteristic. Since = 3, the equality 3 = 2 holds true. -

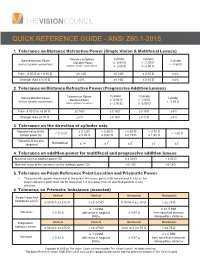

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

INTRODUCTION to ALGEBRAIC GEOMETRY, CLASS 25 Contents 1

INTRODUCTION TO ALGEBRAIC GEOMETRY, CLASS 25 RAVI VAKIL Contents 1. The genus of a nonsingular projective curve 1 2. The Riemann-Roch Theorem with Applications but No Proof 2 2.1. A criterion for closed immersions 3 3. Recap of course 6 PS10 back today; PS11 due today. PS12 due Monday December 13. 1. The genus of a nonsingular projective curve The definition I’m going to give you isn’t the one people would typically start with. I prefer to introduce this one here, because it is more easily computable. Definition. The tentative genus of a nonsingular projective curve C is given by 1 − deg ΩC =2g 2. Fact (from Riemann-Roch, later). g is always a nonnegative integer, i.e. deg K = −2, 0, 2,.... Complex picture: Riemann-surface with g “holes”. Examples. Hence P1 has genus 0, smooth plane cubics have genus 1, etc. Exercise: Hyperelliptic curves. Suppose f(x0,x1) is a polynomial of homo- geneous degree n where n is even. Let C0 be the affine plane curve given by 2 y = f(1,x1), with the generically 2-to-1 cover C0 → U0.LetC1be the affine 2 plane curve given by z = f(x0, 1), with the generically 2-to-1 cover C1 → U1. Check that C0 and C1 are nonsingular. Show that you can glue together C0 and C1 (and the double covers) so as to give a double cover C → P1. (For computational convenience, you may assume that neither [0; 1] nor [1; 0] are zeros of f.) What goes wrong if n is odd? Show that the tentative genus of C is n/2 − 1.(Thisisa special case of the Riemann-Hurwitz formula.) This provides examples of curves of any genus. -

A Three-Dimensional Laguerre Geometry and Its Visualization

A Three-Dimensional Laguerre Geometry and Its Visualization Hans Havlicek and Klaus List, Institut fur¨ Geometrie, TU Wien 3 We describe and visualize the chains of the 3-dimensional chain geometry over the ring R("), " = 0. MSC 2000: 51C05, 53A20. Keywords: chain geometry, Laguerre geometry, affine space, twisted cubic. 1 Introduction The aim of the present paper is to discuss in some detail the Laguerre geometry (cf. [1], [6]) which arises from the 3-dimensional real algebra L := R("), where "3 = 0. This algebra generalizes the algebra of real dual numbers D = R("), where "2 = 0. The Laguerre geometry over D is the geometry on the so-called Blaschke cylinder (Figure 1); the non-degenerate conics on this cylinder are called chains (or cycles, circles). If one generator of the cylinder is removed then the remaining points of the cylinder are in one-one correspon- dence (via a stereographic projection) with the points of the plane of dual numbers, which is an isotropic plane; the chains go over R" to circles and non-isotropic lines. So the point space of the chain geometry over the real dual numbers can be considered as an affine plane with an extra “improper line”. The Laguerre geometry based on L has as point set the projective line P(L) over L. It can be seen as the real affine 3-space on L together with an “improper affine plane”. There is a point model R for this geometry, like the Blaschke cylinder, but it is more compli- cated, and belongs to a 7-dimensional projective space ([6, p. -

Homeomorphisms of the 3-Sphere That Preserve a Heegaard Splitting of Genus Two

PROCEEDINGS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 136, Number 3, March 2008, Pages 1113–1123 S 0002-9939(07)09188-5 Article electronically published on November 30, 2007 HOMEOMORPHISMS OF THE 3-SPHERE THAT PRESERVE A HEEGAARD SPLITTING OF GENUS TWO SANGBUM CHO (Communicated by Daniel Ruberman) Abstract. Let H2 be the group of isotopy classes of orientation-preserving homeomorphisms of S3 that preserve a Heegaard splitting of genus two. In this paper, we construct a tree in the barycentric subdivision of the disk complex of a handlebody of the splitting to obtain a finite presentation of H2. 1. Introduction Let Hg be the group of isotopy classes of orientation-preserving homeomorphisms of S3 that preserve a Heegaard splitting of genus g,forg ≥ 2. It was shown by Goeritz [3] in 1933 that H2 is finitely generated. Scharlemann [7] gave a modern proof of Goeritz’s result, and Akbas [1] refined this argument to give a finite pre- sentation of H2. In arbitrary genus, first Powell [6] and then Hirose [4] claimed to have found a finite generating set for the group Hg, though serious gaps in both ar- guments were found by Scharlemann. Establishing the existence of such generating sets appears to be an open problem. In this paper, we recover Akbas’s presentation of H2 by a new argument. First, we define the complex P (V ) of primitive disks, which is a subcomplex of the disk complex of a handlebody V in a Heegaard splitting of genus two. Then we find a suitable tree T ,onwhichH2 acts, in the barycentric subdivision of P (V )toget a finite presentation of H2. -

Â-Genus and Collapsing

The Journal of Geometric Analysis Volume 10, Number 3, 2000 A A-Genus and Collapsing By John Lott ABSTRACT. If M is a compact spin manifold, we give relationships between the vanishing of A( M) and the possibility that M can collapse with curvature bounded below. 1. Introduction The purpose of this paper is to extend the following simple lemma. Lemma 1.I. If M is a connectedA closed Riemannian spin manifold of nonnegative sectional curvature with dim(M) > 0, then A(M) = O. Proof Let K denote the sectional curvature of M and let R denote its scalar curvature. Suppose that A(M) (: O. Let D denote the Dirac operator on M. From the Atiyah-Singer index theorem, there is a nonzero spinor field 7t on M such that D~p = 0. From Lichnerowicz's theorem, 0 = IDOl 2 dvol = IV~Pl 2 dvol + ~- I•12 dvol. (1.1) From our assumptions, R > 0. Hence V~p = 0. This implies that I~k F2 is a nonzero constant function on M and so we must also have R = 0. Then as K > 0, we must have K = 0. This implies, from the integral formula for A'(M) [14, p. 231], that A"(M) = O. [] The spin condition is necessary in Lemma 1.l, as can be seen in the case of M = CP 2k. The Ricci-analog of Lemma 1.1 is false, as can be seen in the case of M = K3. Definition 1.2. A connected closed manifold M is almost-nonnegatively-curved if for every E > 0, there is a Riemannian metric g on M such that K(M, g) diam(M, g)2 > -E. -

Riemann Surfaces

RIEMANN SURFACES AARON LANDESMAN CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2 2. Maps of Riemann Surfaces 4 2.1. Defining the maps 4 2.2. The multiplicity of a map 4 2.3. Ramification Loci of maps 6 2.4. Applications 6 3. Properness 9 3.1. Definition of properness 9 3.2. Basic properties of proper morphisms 9 3.3. Constancy of degree of a map 10 4. Examples of Proper Maps of Riemann Surfaces 13 5. Riemann-Hurwitz 15 5.1. Statement of Riemann-Hurwitz 15 5.2. Applications 15 6. Automorphisms of Riemann Surfaces of genus ≥ 2 18 6.1. Statement of the bound 18 6.2. Proving the bound 18 6.3. We rule out g(Y) > 1 20 6.4. We rule out g(Y) = 1 20 6.5. We rule out g(Y) = 0, n ≥ 5 20 6.6. We rule out g(Y) = 0, n = 4 20 6.7. We rule out g(C0) = 0, n = 3 20 6.8. 21 7. Automorphisms in low genus 0 and 1 22 7.1. Genus 0 22 7.2. Genus 1 22 7.3. Example in Genus 3 23 Appendix A. Proof of Riemann Hurwitz 25 Appendix B. Quotients of Riemann surfaces by automorphisms 29 References 31 1 2 AARON LANDESMAN 1. INTRODUCTION In this course, we’ll discuss the theory of Riemann surfaces. Rie- mann surfaces are a beautiful breeding ground for ideas from many areas of math. In this way they connect seemingly disjoint fields, and also allow one to use tools from different areas of math to study them. -

Graphs on Surfaces, the Generalized Euler's Formula and The

Graphs on surfaces, the generalized Euler's formula and the classification theorem ZdenˇekDvoˇr´ak October 28, 2020 In this lecture, we allow the graphs to have loops and parallel edges. In addition to the plane (or the sphere), we can draw the graphs on the surface of the torus or on more complicated surfaces. Definition 1. A surface is a compact connected 2-dimensional manifold with- out boundary. Intuitive explanation: • 2-dimensional manifold without boundary: Each point has a neighbor- hood homeomorphic to an open disk, i.e., \locally, the surface looks at every point the same as the plane." • compact: \The surface can be covered by a finite number of such neigh- borhoods." • connected: \The surface has just one piece." Examples: • The sphere and the torus are surfaces. • The plane is not a surface, since it is not compact. • The closed disk is not a surface, since it has a boundary. From the combinatorial perspective, it does not make sense to distinguish between some of the surfaces; the same graphs can be drawn on the torus and on a deformed torus (e.g., a coffee mug with a handle). For us, two surfaces will be equivalent if they only differ by a homeomorphism; a function f :Σ1 ! Σ2 between two surfaces is a homeomorphism if f is a bijection, continuous, and the inverse f −1 is continuous as well. In particular, this 1 implies that f maps simple continuous curves to simple continuous curves, and thus it maps a drawing of a graph in Σ1 to a drawing of the same graph in Σ2.