A Sustainable Regional Downtown?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

List of Mps on the Hill Names Political Affiliation Constituency

List of MPs on the Hill Names Political Affiliation Constituency Adam Vaughan Liberal Spadina – Fort York, ON Alaina Lockhart Liberal Fundy Royal, NB Ali Ehsassi Liberal Willowdale, ON Alistair MacGregor NDP Cowichan – Malahat – Langford, BC Anthony Housefather Liberal Mount Royal, BC Arnold Viersen Conservative Peace River – Westlock, AB Bill Casey Liberal Cumberland Colchester, NS Bob Benzen Conservative Calgary Heritage, AB Bob Zimmer Conservative Prince George – Peace River – Northern Rockies, BC Carol Hughes NDP Algoma – Manitoulin – Kapuskasing, ON Cathay Wagantall Conservative Yorkton – Melville, SK Cathy McLeod Conservative Kamloops – Thompson – Cariboo, BC Celina Ceasar-Chavannes Liberal Whitby, ON Cheryl Gallant Conservative Renfrew – Nipissing – Pembroke, ON Chris Bittle Liberal St. Catharines, ON Christine Moore NDP Abitibi – Témiscamingue, QC Dan Ruimy Liberal Pitt Meadows – Maple Ridge, BC Dan Van Kesteren Conservative Chatham-Kent – Leamington, ON Dan Vandal Liberal Saint Boniface – Saint Vital, MB Daniel Blaikie NDP Elmwood – Transcona, MB Darrell Samson Liberal Sackville – Preston – Chezzetcook, NS Darren Fisher Liberal Darthmouth – Cole Harbour, NS David Anderson Conservative Cypress Hills – Grasslands, SK David Christopherson NDP Hamilton Centre, ON David Graham Liberal Laurentides – Labelle, QC David Sweet Conservative Flamborough – Glanbrook, ON David Tilson Conservative Dufferin – Caledon, ON David Yurdiga Conservative Fort McMurray – Cold Lake, AB Deborah Schulte Liberal King – Vaughan, ON Earl Dreeshen Conservative -

Report of the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of British Columbia 2012

Redistribution Federal Electoral Districts Redécoupage 2012 Circonscriptions fédérales Report of the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of British Columbia 2012 Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représenta- tion à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représenta- tion à la Chambre des communes Your Representation in the House of Commons Votre représentation -

Voting Place Information - General Election 2013 Printed On: 07/05/2013 10:09AM

Page 1 of 85 Voting Place Information - General Election 2013 Printed On: 07/05/2013 10:09AM Electoral District: Abbotsford-Mission District Electoral Officer: Dale Thingvold Phone Number: (604) 820-6100 33171 2nd Ave Mission VP Type Location Name Address City Advance Abbotsford Seniors Assn 2631 Cyril St Abbotsford Voting Place Northside Comm Church 33507 Dewdney Trunk Rd Mission St. Andrew's United Church 7756 Grand St Mission General Voting Abbotsford Christian Middle School 35011 Old Clayburn Rd Abbotsford Place Abbotsford Virtual School 33952 Pine St Abbotsford Auguston Traditional Elem School 36367 Stephen Leacock Dr Abbotsford Deroche Elem School 10340 North Deroche Rd Deroche Dewdney Elem School 37151 Hawkins Pickle Rd Dewdney Edwin S. Richards Elem School 33419 Cherry Ave Mission Hatzic Prairie Comm Hall 10845 Farms Rd Mission Hatzic Sec School 34800 Dewdney Trunk Rd Mission Hillside Elem School 33621 Best Ave Mission Margaret Stenersen Elem School 3060 Old Clayburn Rd Abbotsford Matsqui Elem School 33661 Elizabeth Ave Abbotsford Mission Central Elem School 7466 Welton St Mission Mission Sec School 32939 7th Ave Mission Mountain Elem School 2299 Mountain Dr Abbotsford Prince Charles Elem School 35410 McKee Rd Abbotsford Robert Bateman Sec School 35045 Exbury Ave Abbotsford Sandy Hill Elem School 3836 Old Clayburn Rd Abbotsford Sto:lo First Nation Pekw'xe:yles 34110 Lougheed Hwy Mission Windebank Elem School 33570 11th Ave Mission Page 2 of 85 Voting Place Information - General Election 2013 Printed On: 07/05/2013 10:09AM Electoral -

Reg # Operating As City 13356 # 1 Auto Service COQUITLAM 10980 1 Minute Muffler QUESNEL 10652 100 Mile Tire & Auto Service 1

Tire Stewardship BC List of Retailers as of July 28, 2021 Reg # Operating As City 13356 # 1 Auto Service COQUITLAM 10980 1 Minute Muffler QUESNEL 10652 100 Mile Tire & Auto Service 100 MILE HOUSE 14758 1010Tires LANGLEY 12367 1010tires.com RICHMOND 14781 1147703 B.C. Ltd. MISSION 14741 1235321 B.C. Ltd. SURREY 14936 1266186 BC Ltd. ABBOTSFORD 12838 128 Auto Service Centre COQUITLAM 13134 150 Mile M & S Tire & Service 150 MILE HOUSE 14875 1st Klass Auto Works VERNON 14544 2nd Gear Motorsport Ltd. COQUITLAM 14870 3 Peaks Mechanical Ltd. MCBRIDE 14745 3-D Cycles ABBOTSFORD 14800 4 R 4 Tire Service LANGLEY 14113 4 Wheel Parts LANGLEY 12833 A & A Japanese Engine Specialist RICHMOND 11541 A & A Tire LANGLEY 13529 A & C Automotive BURNABY 12249 A & D Workshop Inc RICHMOND 10678 A & J Motorsport Ltd. COQUITLAM 12782 A & Y Automotive BURNABY 11266 A M Ford Sales Ltd. TRAIL 12992 A Plus Automotive - Kel KELOWNA 11807 A Plus Automotive Ltd. - NV NORTH VANCOUVER 10987 A-All-Tech Auto Service SCOTCH CREEK 10801 Aaron's Automotive Repair Ltd. TSAWWASSEN 12550 Abbotsford - Japan Auto Inc. ABBOTSFORD 10621 Abbotsford Autotech ABBOTSFORD 13691 Abbotsford Chrysler Dodge Jeep ABBOTSFORD 12242 Abbotsford Country Tire LANGLEY 13466 Abbotsford Hyundai ABBOTSFORD 11557 Abbotsford Nissan ABBOTSFORD 13692 Abbotsford Volkswagen ABBOTSFORD 10025 Abbsry New & Used Tires Ltd. CHILLIWACK 11188 Abbsry Used Tires Ltd. ABBOTSFORD 14693 Abby Tires & Auto Repair Ltd. ABBOTSFORD 11632 ABC Main Auto Centre VANCOUVER Tire Stewardship BC List of Retailers as of July 28, 2021 Reg # Operating As City 14072 ABH Car Sales Ltd.. GRAND FORKS 14668 Able Auctions LANGLEY 12697 Able Autobody - Newton SURREY 12696 Able Autobody - Surrey SURREY 14042 Able Tire Services SURREY 12185 ABS Tire RICHMOND 13815 Acco Trailer Manufacturing Ltd. -

Official Report of Debates (Hansard)

Tird Session, 41st Parliament OFFICIAL REPORT OF DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday, May 15, 2018 Morning Sitting Issue No. 137 THE HONOURABLE DARRYL PLECAS, SPEAKER ISSN 1499-2175 PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Entered Confederation July 20, 1871) LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR Her Honour the Honourable Janet Austin, OBC Third Session, 41st Parliament SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Honourable Darryl Plecas EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Premier and President of the Executive Council ............................................................................................................... Hon. John Horgan Deputy Premier and Minister of Finance............................................................................................................................Hon. Carole James Minister of Advanced Education, Skills and Training..................................................................................................... Hon. Melanie Mark Minister of Agriculture.........................................................................................................................................................Hon. Lana Popham Attorney General.................................................................................................................................................................Hon. David Eby, QC Minister of Children and Family Development ............................................................................................................ Hon. Katrine Conroy Minister of State for Child Care......................................................................................................................................Hon. -

Langley City West Vancouver—Sunshine Coast

CITY OF VANCOUVER AND VICINITY VILLE DE VANCOUVER ET LES ENVIRONS GAMBIER ISLAND R BOWYER E IV F R A S E R VA L L E Y F SU N S H I N E C O A S T ISLAND R G R E AT E R VA N C O U V E R A COQUITLAM O LAKE N A L I KEATS A P PITT FR A S E R VA L L E Y E Y C T A ISLAND T LAKE O W R L H K E E R G V L I I A E E H R H N R C N Y C COQUITLAM—PORT COQUITLAM K N A S - E H N O E N C T BOWEN U - W E S T VA N C O U V E R Y CAPILANO L Q A ISLAND E N O R T H VA N C O U V E R , D . M . S LAKE WEST VANCOUVER—SUNSHINE COAST— NORTH M R A R VANCOUVER U SEA TO SKY COUNTRY O UP P ER M L Y EVE HW L S H IG AY E N A N M O R E S PASSAGE IA R 1 2 D E ISLAND V IN I R B E L C A R R A E CAPILANO 5 K M A N O R T H L A VA N C O U V E R L E T T BURRARD T M I S S I O N I PORT MOODY— E M RST INLET 3 U U FI N D A Q O R R L BURRARD MISSION 1 O A A COQUITLAM I R T O R C E C O Q U I T L A M S INLET W R SEYMOUR L S U VANC N O S UVER I CREEK 2 B P O R T M O O D Y R I ENGLISH HARBOUR IVE PITT MEADOWS—MAPLE RIDGE R O BAY PORT MOODY VANCOUVER EAST G R E AT E R N 34 P O R T P I T T M E A D O W S VANCOUVER-EST — VA N C O U V E R C O Q U I T L A M A T LO M E BROADWAY B U R N A B Y T U I E W 16TH AVENUE P T S T M A P L E R I D G E A T E VANCOUVER VA N C O U V E R AUSTIN AVENUE T R VANCOUVER S T S GRANVILLE BURNABY SOUTH A S E P L T N A D RIVER I Y O STAVE E VANCOUVER E B U A A 1 G T R I QUADRA E H O BURNABY-SUD Q LAKE E M E T L 128 AVENUE T R KINGSWAY E R L E D W 41ST AVENUE S I T H H R I S Y G T KI AR HW U E N M S G A L SW R R Y K MUSQUEAM 2 L A IV I E O VANCOUVER SOUT Y E E R DEWDNEY TRUNK ROAD I A H Y V U DOUGLAS — T O N T R N E ISLAND F E A A VANCOUVER-SUD V S F 7 A L E D E R U N V R N H G MARINE S E E T I F D T 19 T R U MARI 0 N S SEA IV E E DRI 1 M KATZIE 1 E O VE E VANCOUVER 0 R G ISLAND B 4 T R H 2 INT. -

Cloverdale Town Centre Heritage Study January 2015

CLOVERDALE TOWN CENTRE HERITAGE STUDY JANUARY 2015 CLOVERDALE TOWN CENTRE HERITAGE STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 2 2.0 Historic Context 3 2.1 The Geography and History of Cloverdale Town Centre 3 2.2 Cartographic History of Cloverdale 10 3.0 Heritage Resources 18 3.1 Map of Heritage Resources 18 3.2 Heritage Opportunities 19 3.2.1 Possible Additions 19 3.2.2 Cultural Landscapes 21 4.0 Heritage Options 22 4.1 Heritage Incentives 22 4.2 Regulations 23 4.3 Relocation 23 4.4 Adaptive Reuse 24 4.5 Commemoration and Historical Interpretation 25 4.6 Historic Area Zoning Guidelines 25 4.7 Partnerships 26 4.8 Case Studies: Heritage Interpretation 26 4.9 Themes of Interpretation 28 5.0 Implementation Methods 29 APPENDIX: Heritage Sites within and adjacent to Cloverdale Town Centre 30 Community Heritage Register Sites that have been Designated 30 Community Heritage Register Sites 34 Heritage Inventory Sites 53 Heritage Sites Adjacent to Cloverdale Town Centre 56 DONALD LUXTON & ASSOCIATES INC. JANUARY 2015 1 CLOVERDALE TOWN CENTRE HERITAGE STUDY 1.0 Introduction Surrey City Council has recently embarked upon a process for reviewing and updating the Cloverdale Town Centre Plan. This Heritage Study is one of several background studies, which will provide input into the Plan update process, and will assist the City in understanding the history of Cloverdale Town Centre, within the broader context of Cloverdale and Surrey. It will help to ensure that opportunities for the conservation, commemoration and interpretation of the area’s heritage are considered in the update of the Town Centre Plan. -

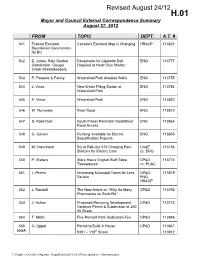

Mayor and Council Correspondence Summary

H.01 Mayor and Council External Correspondence Summary August 27, 2012 FROM TOPIC DEPT. A.T. # 541 Federal Electoral Canada’s Electoral Map is Changing HR&CP 113821 Boundaries Commission for BC 542 D. Jones, Rain Garden Receptacle for Cigarette Butt ENG 113777 Coordinator, Cougar Disposal at Heath Bus Shelter Creek Streamkeepers 543 P. Pawelec & Family Watershed Park Artesian Wells ENG 113755 544 J. Vince New Water Filling Station at ENG 113754 Watershed Park 545 A. Vince Watershed Park ENG 113820 546 W. Nurmeste River Road ENG 113872 547 S. Robertson South Fraser Perimeter Road/River ENG 113864 Road Access 548 G. Gerwin Funding Available for Electric ENG 113855 Beautification Projects 549 M. Vranckaert BC to Roll-Out 570 Charging Port- CA&E 113756 Stations for Electric Cars cc: ENG 550 P. Walters Store Hours English Bluff Store, CP&D 113774 Tsawwassen cc: PU&C 551 J. Peters Increasing Municipal Taxes for Less CP&D, 113819 Service ENG, HR&CP 552 J. Randall The Now Article on “Why So Many CP&D 113792 Pharmacies on Scott Rd.” 553 J. Hutton Proposed Rezoning Development CP&D 113775 Variance Permit & Subdivision at 260 55 Street 554 T. Malhi Five Percent Park Dedication Fee CP&D 113846 555 G. Uppal Permit to Build A House CP&D 113847 9391 – 118th Street 113912 F:\CorpRec Corr-Other\Agenda - Regular\2012\2012-08-27\Correspondence Summary.docx H.01 Mayor and Council External Correspondence Summary August 27, 2012 FROM TOPIC DEPT. A.T. # 556 D. McClure Amanda Lang & David Kaufman CP&D 113790 Interview 557 L. -

List of Persons Entitled to Vote

57 VICT. SUPPLEMENTARY VOTERS' LIST—DELTA RIDING, WESTMINSTER LIST. xiii. SUPPLEMEN TART LIST OF PERSONS ENTITLED TO VOTE IN THE DELTA RIDING OF WESTMINSTER ELECTORAL DISTRICT. 14TH JUNE, 1894. Residence of Claimant. (If in a city or town, the name and side of the street Christian name and surname of the upon which he resides, and the names of the near Profession, trade, or Claimant in full length. est cross streets between which his residence is calling- (if any) situate.) 916 Adamson, Anthony B. 1, Lots 14 and 15, Sec. 31, Tp. 2, SSurreu y Painter 917 Allard, Jason La-ngley Farmer 918 Allen, William .... Elgin Hotel, Surrey Contractor 919 Altree, Harold .... S.W. cor., S.W. |, Sec. 7, Tp. 8, Surrey Centre Clerk 920 Anderson, Peter Langley Parmer 921 Appel Johaim Clover Valley, Surrey Farmer 922 Armstrong, John .. S. E. i Sec. 11, Tp. 2, Surrey Farmer 923 Arthur, William Lot 111, Gp. 2, N.W. Dist., Delta Municipality Farmer 924 Barry, Michael Robert Barry's Hotel, South Westminster, Surrey . Hotel-keeper 925 Bartolish, Sucos Port Guichon, Delta Fisherman 926 Bdgould, Frederick Royal City Camp, Surrey Logger 927 Bennett, Arnold Grant & Kerr's, Ladner's Landing Labourer 928 Bent, Jabez George Seott Road, Surrey Labourer 929 Bertrand, William Aldergrove, Langley Farmer 930 Biggar, Richard Stevens S. E. I Sec. S, Tp. 10, Lochiel, Langley F'armer 93! Biggs, Frederick Pt. S. W. i Sec. 10, Tp. 8, Clayton, Surrey . Farmer 932 Blizard, William Lot 10, Mackie Estate, Langley Farmer 933 Bond, John Sub. S.E. i Sec. 7, Tp. -

Federal Government (CMHC) Investments in Housing ‐ November 2015 to November 2018

Federal Government (CMHC) Investments in Housing ‐ November 2015 to November 2018 # Province Federal Riding Funding* Subsidy** 1 Alberta Banff‐Airdrie$ 9,972,484.00 $ 2,445,696.00 2 Alberta Battle River‐Crowfoot $ 379,569.00 $ 7,643.00 3 Alberta Bow River $ 10,900,199.00 $ 4,049,270.00 4 Alberta Calgary Centre$ 47,293,104.00 $ 801,215.00 5 Alberta Calgary Confederation$ 2,853,025.00 $ 559,310.00 6 Alberta Calgary Forest Lawn$ 1,060,788.00 $ 3,100,964.00 7 Alberta Calgary Heritage$ 107,000.00 $ 702,919.00 8 Alberta Calgary Midnapore$ 168,000.00 $ 261,991.00 9 Alberta Calgary Nose Hill$ 404,700.00 $ 764,519.00 10 Alberta Calgary Rocky Ridge $ 258,000.00 $ 57,724.00 11 Alberta Calgary Shepard$ 857,932.00 $ 541,918.00 12 Alberta Calgary Signal Hill$ 1,490,355.00 $ 602,482.00 13 Alberta Calgary Skyview $ 202,000.00 $ 231,724.00 14 Alberta Edmonton Centre$ 948,133.00 $ 3,504,371.98 15 Alberta Edmonton Griesbach$ 9,160,315.00 $ 3,378,752.00 16 Alberta Edmonton Manning $ 548,723.00 $ 4,296,014.00 17 Alberta Edmonton Mill Woods $ 19,709,762.00 $ 1,033,302.00 18 Alberta Edmonton Riverbend$ 105,000.00 $ ‐ 19 Alberta Edmonton Strathcona$ 1,025,886.00 $ 1,110,745.00 20 Alberta Edmonton West$ 582,000.00 $ 1,068,463.00 21 Alberta Edmonton‐‐Wetaskiwin$ 6,502,933.00 $ 2,620.00 22 Alberta Foothills$ 19,361,952.00 $ 152,210.00 23 Alberta Fort McMurray‐‐Cold Lake $ 6,416,365.00 $ 7,857,709.00 24 Alberta Grande Prairie‐Mackenzie $ 1,683,643.00 $ 1,648,013.00 25 Alberta Lakeland$ 20,646,958.00 $ 3,040,248.00 26 Alberta Lethbridge$ 1,442,864.00 $ 8,019,066.00 27 Alberta Medicine Hat‐‐Cardston‐‐Warner $ 13,345,981.00 $ 4,423,088.00 28 Alberta Peace River‐‐Westlock $ 7,094,534.00 $ 6,358,849.52 29 Alberta Red Deer‐‐Lacombe$ 10,949,003.00 $ 4,183,893.00 30 Alberta Red Deer‐‐Mountain View $ 8,828,733.00 $ ‐ 31 Alberta Sherwood Park‐Fort Saskatchewan$ 14,298,902.00 $ 1,094,979.00 32 Alberta St. -

Electoral Framework Association

EFA ELECTORAL FRAMEWORK ASSOCIATION (BC BRANCH) By Fred Subra (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], Commons Subra (Own work) [CC BY-SA By Fred PHOTO: PROPOSAL FOR STRUCTURING THE 2018 ELECTORAL REFORM BALLOT SUBMITTED ON BEHALF OF ELECTORAL FRAMEWORK ASSOCIATION (BC) February 27, 2018 What it the Electoral Framework Association? The Electoral Framework Association (BC) is a non-partisan association of individuals working to modernize electoral systems and promote industry best practices. ([email protected]) The Electoral Framework Association - Chair Daniel A Grice, JD is an Abbotsford lawyer and chair of the Electoral Framework Association. He has worked with electoral reform organizations as a director and campaign organizer in provincial referendum campaigns in 2005 and 2009. Mr. Grice is co-author of Establishing a Framework for E- Voting in Canada. [Elections Canada: 2013 Site: http://www.elections.ca/res/rec/tech/elfec/pdf/ elfec_e.pdf] EFA ! ! STRUCTURING THE 2018 ELECTORAL REFORM BALLOT It is my conclusion that the purpose of the right to vote enshrined in s. 3 of the Charter is not equality of voting power per se, but the right to "effective representation". Ours is a representative democracy. Each citizen is entitled to be represented in government. Representation comprehends the idea of having a voice in the deliberations of government as well as the idea of the right to bring one's grievances and concerns to the attention of one's government representative; as noted in Dixon v.