Postmodernism and the Professional String Quartet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kronos Quartet Prelude to a Black Hole Beyond Zero: 1914-1918 Aleksandra Vrebalov, Composer Bill Morrison, Filmmaker

KRONOS QUARTET PRELUDE TO A BLACK HOLE BeyOND ZERO: 1914-1918 ALeksANDRA VREBALOV, COMPOSER BILL MORRISon, FILMMAKER Thu, Feb 12, 2015 • 7:30pm WWI Centenary ProJECT “KRONOs CONTINUEs With unDIMINISHED FEROCity to make unPRECEDENTED sTRING QUARtet hisTORY.” – Los Angeles Times 22 carolinaperformingarts.org // #CPA10 thu, feb 12 • 7:30pm KRONOS QUARTET David Harrington, violin Hank Dutt, viola John Sherba, violin Sunny Yang, cello PROGRAM Prelude to a Black Hole Eternal Memory to the Virtuous+ ....................................................................................Byzantine Chant arr. Aleksandra Vrebalov Three Pieces for String Quartet ...................................................................................... Igor Stravinsky Dance – Eccentric – Canticle (1882-1971) Last Kind Words+ .............................................................................................................Geeshie Wiley (ca. 1906-1939) arr. Jacob Garchik Evic Taksim+ ............................................................................................................. Tanburi Cemil Bey (1873-1916) arr. Stephen Prutsman Trois beaux oiseaux du Paradis+ ........................................................................................Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) arr. JJ Hollingsworth Smyrneiko Minore+ ............................................................................................................... Traditional arr. Jacob Garchik Six Bagatelles, Op. 9 ..................................................................................................... -

Nasher Sculpture Center's Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Macke

Nasher Sculpture Center’s Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Mackey to be Performed at City Performance Hall; Guaranteed Seating with Soundings Season Ticket Package Brentano String Quartet Performance of One Red Rose, co-commissioned by the Nasher with Carnegie Hall and Yellow Barn, moved to accommodate bigger audience. DALLAS, Texas (September 12, 2013) – The Nasher Sculpture Center is pleased to announce that the JFK commemorative Soundings concert will be performed at City Performance Hall. Season tickets to Soundings are now on sale with guaranteed seating to the special concert honoring President Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his death with an important new work by internationally renowned composer Steven Mackey. One Red Rose is written for the Brentano String Quartet in commemoration of this anniversary, and is commissioned by the Nasher (Dallas, TX) with Carnegie Hall (New York, NY) and Yellow Barn (Putney, VT). The concert will be held on Saturday, November 23, 2013 at 7:30 pm at City Performance Hall with celebrated musicians; the Brentano String Quartet, clarinetist Charles Neidich and pianist Seth Knopp. Mr. Mackey’s One Red Rose will be performed along with seminal works by Olivier Messiaen and John Cage. An encore performance of One Red Rose, will take place Sunday, November 24, 2013 at 2 pm at the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. Both concerts will include a discussion with the audience. Season tickets are now available at NasherSculptureCenter.org and individual tickets for the November 23 concert will be available for purchase on October 8, 2013. -

The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2013-2014 THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC THE CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY oF LINCOLN CENTER Thursday, April 10, 2014 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC Endowed by the late composer and pianist Dina Koston (1929-2009) and her husband, prominent Washington psychiatrist Roger L. Shapiro (1927-2002), the DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC supports commissions and performances of contemporary music. Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. Presented in association with: The Chamber Music Society’s touring program is made possible in part by the Lila Acheson and DeWitt Wallace Endowment Fund. Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Thursday, April 10, 2014 — 8 pm THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC THE CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY oF LINCOLN CENTER • Gilles Vonsattel, piano Nicolas Dautricourt, violin Nicolas Altstaedt, cello Amphion String Quartet Katie Hyun, violin David Southorn, violin Wei-Yang Andy Lin, viola Mihai Marica, cello Tara Helen O'Connor, flute Romie de Guise-Langlois, clarinet Jörg Widmann, clarinet Ian David Rosenbaum, percussion 1 Program PIERRE JALBERT (B. -

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2008 Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective Alejandro Marcelo Drago University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Drago, Alejandro Marcelo, "Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective" (2008). Dissertations. 1107. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved: May 2008 COPYRIGHT BY ALEJANDRO MARCELO DRAGO 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2008 ABSTRACT INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

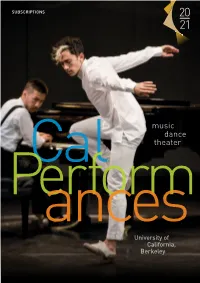

2020-21-Brochure.Pdf

SUBSCRIPTIONS 20 21 music dance Ca l theater Performances University of California, Berkeley Letter from the Director Universities. They exist to foster a commitment to knowledge in its myriad facets. To pursue that knowledge and extend its boundaries. To organize, teach, and disseminate it throughout the wider community. At Cal Performances, we’re proud of our place at the heart of one of the world’s finest public universities. Each season, we strive to honor the same spirit of curiosity that fuels the work of this remarkable center of learning—of its teachers, researchers, and students. That’s why I’m happy to present the details of our 2020/21 Season, an endlessly diverse collection of performances rivaling any program, on any stage, on the planet. Here you’ll find legendary artists and companies like cellist Yo-Yo Ma, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra with conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the Mark Morris Dance Group, pianist Mitsuko Uchida, and singer/songwriter Angélique Kidjo. And you’ll discover a wide range of performers you might not yet know you can’t live without—extraordinary, less-familiar talent just now emerging on the international scene. This season, we are especially proud to introduce our new Illuminations series, which aims to harness the power of the arts to address the pressing issues of our time and amplify them by shining a light on developments taking place elsewhere on the Berkeley campus. Through the themes of Music and the Mind and Fact or Fiction (please see the following pages for details), we’ll examine current groundbreaking work in the university’s classrooms and laboratories. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008). -

Kronos Quartet

K RONOS QUARTET SUNRISE o f the PLANETARY DREAM COLLECTOR Music o f TERRY RILEY TERRY RILEY (b. 1935) KRONOS QUARTET David Harrington, VIOLIN 1. Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector 12:31 John Sherba, VIOLIN Hank Dutt, VIOLA 2. One Earth, One People, One Love 9:00 CELLO (1–2) from Sun Rings Sunny Yang, Joan Jeanrenaud, CELLO (3–4, 6–16) 3. Cry of a Lady 5:09 with Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares Jennifer Culp, CELLO (5) Dora Hristova, conductor 4. G Song 9:39 5. Lacrymosa – Remembering Kevin 8:28 Cadenza on the Night Plain 6. Introduction 2:19 7. Cadenza: Violin I 2:34 8. Where Was Wisdom When We Went West? 3:05 9. Cadenza: Viola 2:24 10. March of the Old Timers Reefer Division 2:19 11. Cadenza: Violin II 2:02 12. Tuning to Rolling Thunder 4:53 13. The Night Cry of Black Buffalo Woman 2:53 1 4. Cadenza: Cello 1:08 15. Gathering of the Spiral Clan 5:24 16. Captain Jack Has the Last Word 1:42 from left: Joan Jeanrenaud, John Sherba, Terry Riley, Hank Dutt, and David Harrington (1983, photo by James M. Brown) Sunrise of the Planetary possibilities of life. It helped the Dream Collector (1980) imagination open up to the possibilities It had been raining steadily that day surrounding us, to new possibilities in 1980 when the Kronos Quartet drove up curiosity he stopped by to hear the quartet Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector for interpretation.” —John Sherba to the Sierra Foothills to receive Sunrise practice. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

“Music of Our Time” When I worked at Columbia Records during the second half of the 1960s, the company was run in an enlightened way by its imaginative president, Goddard Lieberson. Himself a composer and a friend to many writers, artists, and musicians, Lieberson believed that a major record company should devote some of its resources to projects that had cultural value even if they didn’t bring in big profits from the marketplace. During those years American society was in crisis and the Vietnam War was raging; musical tastes were changing fast. It was clear to executives who ran record companies that new “hits” appealing to young people were liable to break out from unknown sources—but no one knew in advance what they would be or where they would come from. Columbia, successful and prosperous, was making plenty of money thanks to its Broadway musical and popular music albums. Classical music sold pretty well also. The company could afford to take chances. In that environment, thanks to Lieberson and Masterworks chief John McClure, I was allowed to produce a few recordings of new works that were off the beaten track. John McClure and I came up with the phrase, “Music of Our Time.” The budgets had to be kept small, but that was not a great obstacle because the artists whom I knew and whose work I wanted to produce were used to operating with little money. We wanted to produce the best and most strongly innovative new work that we could find out about. Innovation in those days had partly to do with creative uses of electronics, which had recently begun changing music in ways that would have been unimaginable earlier, and partly with a questioning of basic assumptions. -

Kronos Quartet Five Tango Sensations Mp3, Flac, Wma

Kronos Quartet Five Tango Sensations mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Latin Album: Five Tango Sensations Country: US Released: 1991 Style: Tango MP3 version RAR size: 1657 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1417 mb WMA version RAR size: 1164 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 597 Other Formats: ADX WMA MOD MMF APE MIDI AAC Tracklist Five Tango Sensation (26:46) 1 Asleep 5:23 2 Loving 6:10 3 Anxiety 4:51 4 Despertar 6:03 5 Fear 4:00 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Elektra Entertainment Copyright (c) – Elektra Entertainment Made By – WEA Manufacturing Inc. Credits Art Direction, Design – Manhattan Design Bandoneon – Astor Piazzolla Cello – Joan Jeanrenaud Engineer – Dan Gellert, Dave O'Donnell, Judith Sherman, Rob Eaton Executive-Producer – Robert Hurwitz Producer – Judith Sherman Viola – Hank Dutt Violin – David Harrington, John Sherba Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 7559-79254-2 5 Matrix / Runout: 2 79254-2 SRC=04 SPARS Code: DDD Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Astor Astor Piazzolla, Piazzolla, Kronos Quartet With Elektra 7559-79254-2 Kronos Astor Piazzolla - Five 7559-79254-2 Europe 1991 Nonesuch Quartet With Tango Sensations Astor Piazzolla (CD, MiniAlbum) Kronos Quartet With Elektra, Kronos 9 79254-4, Astor Piazzolla - Five Nonesuch, 9 79254-4, Quartet With US 1991 79254-4 Tango Sensations Elektra, 79254-4 Astor Piazzolla (Cass, MiniAlbum) Nonesuch Astor Astor Piazzolla, Piazzolla, Kronos Quartet With Elektra 7559-79254-2 Kronos Astor Piazzolla - Five 7559-79254-2 Europe -

Michael Nyman a Zed & Two Noughts Mp3, Flac, Wma

Michael Nyman A Zed & Two Noughts mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical / Stage & Screen Album: A Zed & Two Noughts Country: UK Released: 1988 Style: Soundtrack, Contemporary MP3 version RAR size: 1686 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1875 mb WMA version RAR size: 1321 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 883 Other Formats: AIFF RA MPC MP2 AA DXD DMF Tracklist 1 Angelfish Decay 2:53 2 Car Crash 3:47 3 Time Lapse 4:01 4 Prawn Watching 2:58 5 Biscosis Populi 2:26 6 Swan Rot 2:47 7 Delft Waltz 4:11 8 Up For Crabs 2:51 9 Vermeer's Wife 3:17 10 Venus De Milo 2:27 11 Lady In The Red Hat 4:18 12 L'Escargot 5:43 Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Jay Productions Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – British Film Institute Phonographic Copyright (p) – Allarts Entertprises Phonographic Copyright (p) – Artificial Eye Productions Phonographic Copyright (p) – Film Four International Manufactured By – TER Limited Recorded At – Vara Studio Recorded At – Berry Street Studio Recorded At – Olympic Studios Mixed At – Vara Studio Mixed At – Berry Street Studio Mixed At – Olympic Studios Mastered At – CBS Studios Credits Coordinator [Album Release Co-ordination] – David Stoner Design – Pens Executive-Producer – John Yap Harpsichord, Music By, Conductor [Music Conducted By], Producer, Composed By – Michael Nyman Performer – The Zoo Orchestra Photography By [Photo] – Eric Richmond , Steve Pyke Producer – David Cunningham Violin – Alexander Balanescu, Elisabeth Perry Voice – Sarah Leonard Notes Title shown as follows: "A ZED & TWO NOUGHTS" - spine, label "MICHAEL NYMAN'S