A Sentencing Problem: How Far Is a Fall from Grace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibit C: Studies That Were Not Included in the NTT and COT Reports

Exhibit C: Studies that Were Not Included in the NTT and COT Reports I. Tall Structures The NTT and COT Reports do not reflect the current understanding of the impacts of tall structures to GRSG. The studies cited below are those which either should have been considered or have changed the understanding of impacts to GRSG. A. Studies Ignored Messmer, T. A., R. Hasenyager, and J. Burruss. 2010. Contemporary Knowledge and Research Needs Regarding the Effects of Tall Structures on Sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus and C. minimus). Utah Wildlife in Need Foundation. Salt Lake City, Utah. Messmer, T.A. 2011. Protocols for Investigating the Effects of Tall Structure on Sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus). Utah Wildlife in Need Foundation. Salt Lake City, Utah. Utah Wildlife in Need (UWIN). 2010. Contemporary Knowledge and Research Needs Regarding the Potential Effects of Tall Structures on Sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus and C. minimus). http://www.utahcbcp.org/htm/tall-structure-info B. Additional Studies that Must be Considered LeBeau, C.W. 2012. Evaluation of Greater Sage-Grouse Reproductive Habitat and Response to Wind Energy Development in south-Central Wyoming, MS Thesis, Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, University of Wyoming. August 2012. Messmer, T., A., R. Hasenyager, J. Burruss, and S. Liguori. 2013. Stakeholder contemporary knowledge needs regarding the potential effects of tall structures on sage-grouse. Human- Wildlife Interactions 7(2):273-298. Nonne, D., E. Blomberg, and J. Sedinger. 2013. Dynamics of Greater Sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) populations in response to transmission lines in central Nevada. Progress Report: Year 10. February 2013. Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, University of Nevada, Reno. -

Must-Read Debut Novels @ San Rafael Public Library

Must-Read Debut Novels @ San Rafael Public Library Taken BY Scott Bergstrom meets The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Bourne Identity in this action-packed debut thriller (optioned for film by Jerry Bruckheimer) about a girl who must train as an assassin to deal with the gangsters who have kidnapped her father. Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe: “Things Fall Apart—the first volume of Chinua Achebe’s masterpiece The African Trilogy—tells two intertwining stories, both centering on Okonkwo, a “strong man” of an Igbo village in Nigeria. The first, a powerful fable of the immemorial conflict between the individual and society, traces Okonkwo’s fall from grace in his world. The second, as modern as the first is ancient, concerns the clash of cultures and the destruction of that world when European missionaries arrive in his village.” Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: “Fifteen-year-old Kambili and her older brother Jaja lead a privileged life in Enugu, Nigeria. They live in beautiful house, with a caring family, and attend an exclusive missionary school. They’re completely shielded from the troubles of the world. Yet, as Kambili reveals in her tender-voiced account, things are less perfect than they appear.” The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende: “One of the most important novels of the twentieth century, The House of the Spirits is an enthralling epic that spans decades and lives, weaving the personal and the political into a universal story of love, magic, and fate.” Bastard Out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison: “At the heart of this story is Ruth Anne Boatwright, known simply as Bone, a bastard child who observes the world around her with a mercilessly keen perspective. -

PW Remainder Ad

PW ANNOUNCEMENT - May 20, 2019 LAST DAY OF RETURNS - November 30, 2019 October 2019 Full Remainder COVER FMT (13) ISBN TITLE AUTHOR PRICE Avery and Tarcher Perigree TR 9780143109617 WAVE MARTIN, SHANTELL $15.00 Division 17 HC 9781623366728 ICE CREAM ADVENTURES FERRARI, STEF $24.99 TR 9781623362065 FUTURECHEFS GANESHRAM, RAMIN $24.99 HC 9781623368609 SICK LIFE WATKINS, TIONNE $26.99 HC 9781623366629 OASIS IN TIME PAUL, MARILYN $25.99 HC 9781623368173 STIMULATI EXPERIENCE, THE CURTIS, JIM $25.99 HC 9780525573555 THIS IS ME, PERIOD. COWELL, PHILIP $15.99 HC 9780451497987 DIET RIGHT FOR YOUR PERSONALIT WIDERSTROM, JEN $26.00 HC 9780609609156 ART OF SHAVING ZAOUI, MYRIAM $17.50 HC 9781623364762 LOSE WEIGHT HERE TETA, JADE $25.99 HC 9781623366681 DNA RESTART MOALEM, SHARON $26.99 HC 9780307884978 FUTURE OF GOD, THE CHOPRA, DEEPAK MD $25.00 HC 9781623365714 TIGHTEN YOUR TUMMY IN 2 WEEKS DARDEN, ELLINGTON PHD $26.99 HC 9781594867446 INTELLECTUAL DEVOTION:AMERHIST KIDDER, DAVID S. $24.00 HC 9781623365158 MEN'S HEALTH:UNCOMMON KNOWLEDG EDITORS OF MEN'S HEALTH $24.99 HC 9781623367220 BODYWISE ABRAMS, RACHEL CARLTON MD$24.99 HC 9781623360450 SOUTH BEACH DIET GLUTEN SOLN AGATSTON, ARTHUR $25.99 HC 9781623362935 HD DIET GILBERT, KEREN $25.99 Random House HC 9780812998726 ADDLANDS BULLOUGH, TOM $27.00 HC 9781400069026 AMERICAN ULYSSES WHITE, RONALD C. $35.00 HC 9780812995152 BALLROOM, THE HOPE, ANNA $27.00 HC 9780399591655 BEAUTY IN THE BROKEN PLACES PATAKI, ALLISON $26.00 HC 9780399592270 CONFESSIONS OF THE FOX ROSENBERG, JORDY $27.00 HC 9780812998429 DINOSAURS ON OTHER PLANETS MCLAUGHLIN, DANIELLE $27.00 HC 9780525508748 DISTANCE HOME, THE SAUNDERS, PAULA $27.00 HC 9781400065561 HECKUVA JOB, A TRILLIN, CALVIN $12.95 HC 9780525508717 HIGH SEASON, THE BLUNDELL, JUDY $27.00 HC 9780812996081 MILLER'S VALLEY QUINDLEN, ANNA $28.00 HC 9780812998023 PILGRIMAGE SHRIVER, MARK K. -

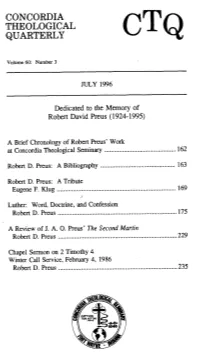

Luther: Word, Doctrine, and Confession Robert D

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 60: Number 3 JULY 1996 Dedicated to the Memory of Robert David Preus (1924-1995) A Brief Chronology of Robert Preus' Work at Concordia Theological Seminary ............................................ 162 Robert D. Preus: A Bibliography ....................... ................. 163 Robert D. Preus: A Tribute Eugene F. Klug ........................................................................ 169 i Luther: Word, Doctrine, and Confession Robert D. Preus ......................................................................... 175 A Review of J. A. 0. Preus' The Second Martin Robert D. Preus ........................................................................ 229 Chapel Sem~onon 2 Timothy 4 Winter Call Service, February 4, 1986 Robert D. Preus ......................................................................... 235 CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY ISSN 0038-8610 The CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY, a continuation of The Springfielder, is a theological journal of the Lutheran Church- Missouri Synod, published for its ministerium by the faculty of Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne, Indiana. Heino 0. Kadai, Editor; Douglas McC. L. Judisch, Associate Editor; Lawrence R. Rast, Jr., Assistant Editor: William C. Weinrich, Book Review Editor, Gregory J. Lockwood, Richard E. Muller, Robert D. Newton, Dean 0. Wenthe, Members of the Editorial Committee. The Faculty: James G. Bollhagen, Eugene W. Bunkowske, Lane A. Burgland, Daniel L. Gard, Douglas McC. L. Judisch, Arthur A. Just, Heino 0. Kadai, -

Jay Weigel 504.258.8299 Selected Film and Recording Credits [email protected]

Jay Weigel 504.258.8299 Selected Film and Recording Credits [email protected] Jay Weigel is a distinguished composer, producer, conductor, arranger, orchestrator, and contractor for film, television, recordings, and concerts. Based in New Orleans, he has worked in the film and television industry since 19. His recent scores and soundtrack recordings can be heard in studio projects produced by Warner Brothers, Paramount Pictures, Universal, Netflix, Tyler Perry Studios, and numerous documentaries and independent films such as: The Campaign, Green Lantern, Grudge Match, Get Hard, Midnight Special, A Fall From Grace, Caged No More, Camp Cool Kids,The Oval, For Colored Girls, Too Close To Home, The Last laugh, Paradise Lost, The Highwaymen, and NCIS New Orleans. He has worked as an orchestrator, conductor, contractor and/or score preparer for composers such as George S. Clinton, Christopher Young, David Wingo, Jon Swihart, Christopher Lennertz and Terence Blanchard. As an arranger and orchestrator, he has worked with PJ Morton, Andra Day, REM, Tank and the Bangas, Chris Thomas King, and Judith Owen. Select Credits Film/TV Scores Director Producer/Studio Unexpected Modernism Gregory Kallenberg Chris Lyons The Oval (new series 25 episodes) Tyler Perry Antoinetta Hairston A Fall from Grace Tyler Perry Michelle Sneed Eagle and the Albatross Angela Shelton Mike Montgomery The Last Laugh Greg Pritikin Rob Paris/Netflix Heart, Baby! Angela Shelton Kim Barnard Boo 2! A Madea Halloween (end titles) Tyler Perry Ozzie Areu The True Don Quixote Chris -

How to Read Literature Like a Professor Notes

How to Read Literature Like a Professor (Thomas C. Foster) Notes Introduction Archetypes: Faustian deal with the devil (i.e. trade soul for something he/she wants) Spring (i.e. youth, promise, rebirth, renewal, fertility) Comedic traits: tragic downfall is threatened but avoided hero wrestles with his/her own demons and comes out victorious What do I look for in literature? - A set of patterns - Interpretive options (readers draw their own conclusions but must be able to support it) - Details ALL feed the major theme - What causes specific events in the story? - Resemblance to earlier works - Characters’ resemblance to other works - Symbol - Pattern(s) Works: A Raisin in the Sun, Dr. Faustus, “The Devil and Daniel Webster”, Damn Yankees, Beowulf Chapter 1: The Quest The Quest: key details 1. a quester (i.e. the person on the quest) 2. a destination 3. a stated purpose 4. challenges that must be faced during on the path to the destination 5. a reason for the quester to go to the destination (cannot be wholly metaphorical) The motivation for the quest is implicit- the stated reason for going on the journey is never the real reason for going The real reason for ANY quest: self-knowledge Works: The Crying of Lot 49 Chapter 2: Acts of Communion Major rule: whenever characters eat or drink together, it’s communion! Pomerantz 1 Communion: key details 1. sharing and peace 2. not always holy 3. personal activity/shared experience 4. indicates how characters are getting along 5. communion enables characters to overcome some kind of internal obstacle Communion scenes often force/enable reader to empathize with character(s) Meal/communion= life, mortality Universal truth: We all eat to live, we all die. -

Reshaping Opera

Reshaping Opera Reshaping Opera: A Critical Reflection on Arts Management By Paola Trevisan Reshaping Opera: A Critical Reflection on Arts Management Series: “Schwung”; Critical Curating and Aesthetic Management for Art, Business and Politics By Paola Trevisan This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Paola Trevisan All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9886-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9886-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 5 Overture Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 15 An Overview of Opera Production Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 31 The Italian Opera Sector: A Fall from Grace Chapter Four ............................................................................................. -

Fall from Grace

Fall from Grace By Kristi Hardison Chapter 1 Grace. That’s what my mother named me. Perhaps she had different visions for my future… or one hell of a sense of humor. I run my hands up and down the black straps of my cheap back pack. Imagine Dragons blasting in my ears. “The beast inside” vibrates through my head. It feels like a movie with an amazing soundtrack. The traffic and people almost appear to be in slow motion and the world around me looks a little less bleak as though I’m some sort of heroine figuring her life out. Everything works out for those people… always. I find myself here every day, waiting for the public transit bus to take me to and from two jobs all so I can hand over nearly every cent to pay for a roach infested, sorry excuse for an apartment that has about an arm span between the toilet and kitchen sink. After bus fares and the occasional textbook for my nursing courses, I barely have enough to eat. I suppose I shouldn’t complain about having food in my stomach. I just always wished for so much more. I look at my watch and seriously begin to worry that I’m going to be late, yet again. God, I’d kill someone for a car. Literally. Riding public transportation in a city like New York was like playing Russian roulette with dishonest people. If you didn’t die from contracting a rare disease formed by an unknown super bacteria, you could surely get robbed, raped or murdered for something as small as the last 20 dollars in your pocket. -

A Suggested Source of Some Expressions in The. Baptist Confession of Faith, London 1644

A Suggested Source of Some Expressions in the. Baptist Confession of Faith, London 1644. HE purpose of this paper' is to draw attention to a probable T source of some of the doctrinal expressions in the Con fession of the Seven Churches issued in London in 1644. This is a well-known and justly prized document of the Baptist churches who accepted the Calvinistic tradition and has often been described so that it is unnecessary to enlarge upon the conditions of its appearance. It may be sufficient to remark that the Baptists were not allowed any place in the deliberations of the Westminster Assembly of Divines who had been summoned by the English Parliament to adjust the religious affairs to the nation in view of the changed conditions of the period. The Royal favour was neither sought nor given, but the purpose of the Assembly had the hearty approbation of the Scottish Presbyterians. The latter were represented by Commissioners of weighty learning and con troversial ability whose animus against all that smacked of Anabaptism is notorious, and it may be taken for granted that while they had any influence upon .the deliberations in the Jerusalem Chamber all pleas that the Baptists should be given an opportunity to declare their mind would be rejected with a perfeot scorn? This exclusion only stimulated the productive activity of the Baptist apologists, and the great debate of those stirring times was given an impetus which is astonishing in its magnitude. For the next decade and more, pamphlet after pamphlet poured from the printing presses. -

Firing Back: How Great Leaders Rebound After Career Disasters

www.hbr.org The leader’s fall from “Who’s Who” to “Who’s that?” is full Firing Back of stigma and shame. But the How Great Leaders Rebound After Career story doesn’t have to end there. Disasters by Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld and Andrew J. Ward Reprint R0701G The leader’s fall from “Who’s Who” to “Who’s that?” is full of stigma and shame. But the story doesn’t have to end there. Firing Back How Great Leaders Rebound After Career Disasters by Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld and Andrew J. Ward Among the tests of a leader, few are more These stories are still the exception rather challenging—and more painful—than recov- than the rule. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s famous ob- ering from a career catastrophe, whether it is servation that there are no second acts in caused by natural disaster, illness, misconduct, American lives casts an especially dark shadow slipups, or unjust conspiratorial overthrow. over the derailed careers of business leaders. In But real leaders don’t cave in. Defeat energizes our research—analyzing more than 450 CEO them to rejoin the fray with greater determi- successions between 1988 and 1992 at large, nation and vigor. publicly traded companies—we found that only Take the case of Jamie Dimon, who was fired 35% of ousted CEOs returned to an active exec- as president of Citigroup but now is CEO of JP- utive role within two years of departure; 22% Morgan Chase. Or look at Vanguard founder stepped back and took only advisory roles, gen- Jack Bogle, who was removed from his posi- erally counseling smaller organizations or sit- tion as president of Wellington Management ting on boards. -

J. Joseph Marr, MD

Fall from grace J. Joseph Marr, MD The author (AΩA, Johns Hopkins as there a certain time when Whenever it occurred, the transforma- University, 1964) is a retired academic it happened? If so, probably tion of the physician during the sec- physician and business executive. He is the inflection point occurred ond half of the twentieth century from a member of the editorial board of The Win the nineties when business took over shaman to skilled labor was inexorable Pharos. formally. That was a watershed series and, in my opinion, will prove to be of events, surely, but the full process irreversible. Illustrations by Jim M’Guinness. seems to have been more like death from All of us who were active in medicine a thousand cuts, some self-inflicted. and medical science during these years 8 The Pharos/Winter 2014 played a role in its transformation. We Two things happened in 1961, when I their time to patient care and paid little were troubled—and then horrified— was a sophomore in medical school, that attention to the institutions in which observers, yet often more than a little were to some degree prophetic. I recog- the care was delivered unless there were complicit. Hubris had much to do with nized both of them as being significant, obvious issues of neglect or mismanage- it, and all of us were culpable to varying but did not see that they were harbingers ment. They also paid little attention to degrees. Is medicine today better, worse, of the future. An article in the Journal patients themselves beyond the office or just different? Does it matter? Perhaps of the American Medical Association or hospital visits. -

Article on the 9 Year Change by Thomas Poplawski Matthew Was An

Article on the 9 Year Change by Thomas Poplawski Matthew was an angel as a young child – sensitive, well-behaved, affectionate, often joyful, and often dreaming away on another plane. After turning nine, however, he soon changed into quite a different person. He was sometimes rude and critical, and often moody if not downright wretched. He had definitely come crashing down to earth, but what a rude awaking for those around him! Child development specialists have long recognized that between ages nine and ten children undergo a marked change. Some experts describe this transition as the crossing of the dividing line between early childhood and full childhood, while others speak in more romantic terms of a “fall from grace.” The psychologist Louise Bates Ames has written a series of parent guides describing each year of child development. While her book on the eight-year-old bears the subtitle “Lively & Outgoing,” the book on age nine bears the more somber “Thoughtful & Mysterious” as its subtitle. So what is going on? Almost a century ago, Rudolf Steiner studied the developmental stages of childhood. He identified three seven-year stages in the child’s passage from birth to adulthood. At birth the child emerges as an independent physical being in the world. But according to Steiner, the unique individuality or ego of the child incarnates or takes hold of this body only gradually. In each of the seven-year stages, the ego manifests itself more fully. The first glimmer of this individuality occurs when the child turns two. Taking place partway through the first seven-year period (birth to age seven), this stage of development is commonly known as “the terrible twos”! What makes this time terrible is that the child is making his first concerted effort to be recognized as a separate person.