Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Making Mutations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reforming Eugenics

Working Papers on the Nature of Evidence: How Well Do “Facts” Travel? No. 12/06 Confronting the Stigma of Perfection: Genetic Demography, Diversity and the Quest for a Democratic Eugenics in the Post-war United States Edmund Ramsden © Edmund Ramsden Department of Economic History London School of Economics August 2006 how ‘facts’ “The Nature of Evidence: How Well Do ‘Facts’ Travel?” is funded by The Leverhulme Trust and the E.S.R.C. at the Department of Economic History, London School of Economics. For further details about this project and additional copies of this, and other papers in the series, go to: http://www.lse.ac.uk/collection/economichistory/ Series Editor: Dr. Jon Adams Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 20 7955 6727 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 Confronting the Stigma of Perfection: Genetic Demography, Diversity and the Quest for a Democratic Eugenics in the Post- war United States1 Edmund Ramsden Abstract Eugenics has played an important role in the relations between social and biological scientists of population through time. Having served as a site for the sharing of data and methods between disciplines in the early twentieth century, scientists and historians have tended to view its legacy in terms of reduction and division - contributing distrust, even antipathy, between communities in the social and the biological sciences. Following the work of Erving Goffman, this paper will explore how eugenics has, as the epitome of “bad” or “abnormal” science, served as a “stigma symbol” in the politics of boundary work. -

The Gigas Effect: a Reliable Predictor of Ploidy? Case Studies in Oxalis

The gigas effect: A reliable predictor of ploidy? Case studies in Oxalis by Frederik Willem Becker Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Faculty of Science at Stellenbosch University Supervisors: Prof. Léanne L.Dreyer, Dr. Kenneth C. Oberlander, Dr. Pavel Trávníček March 2021 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2021 …………………………. ………………… F.W. Becker Date Copyright © 2021 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Whole Genome Duplication (WGD), or polyploidy is an important evolutionary process, but literature is divided over its long-term evolutionary potential to generate diversity and lead to lineage divergence. WGD often causes major phenotypic changes in polyploids, of which the most prominent is the Gigas effect. The Gigas effect refers to the enlargement of plant cells due to their increased amount of DNA, causing plant organs to enlarge as well. This enlargement has been associated with fitness advantages in polyploids, enabling them to successfully establish and persist, eventually causing speciation. Using Oxalis as a study system, I examine whether Oxalis polyploids exhibit the Gigas effect using 24 species across the genus from the Oxalis living research collection at the Stellenbosch University Botanical Gardens, Stellenbosch. -

Models of the Gene Must Inform Data-Mining Strategies in Genomics

entropy Review Models of the Gene Must Inform Data-Mining Strategies in Genomics Łukasz Huminiecki Department of Molecular Biology, Institute of Genetics and Animal Biotechnology, Polish Academy of Sciences, 00-901 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] Received: 13 July 2020; Accepted: 22 August 2020; Published: 27 August 2020 Abstract: The gene is a fundamental concept of genetics, which emerged with the Mendelian paradigm of heredity at the beginning of the 20th century. However, the concept has since diversified. Somewhat different narratives and models of the gene developed in several sub-disciplines of genetics, that is in classical genetics, population genetics, molecular genetics, genomics, and, recently, also, in systems genetics. Here, I ask how the diversity of the concept impacts data-integration and data-mining strategies for bioinformatics, genomics, statistical genetics, and data science. I also consider theoretical background of the concept of the gene in the ideas of empiricism and experimentalism, as well as reductionist and anti-reductionist narratives on the concept. Finally, a few strategies of analysis from published examples of data-mining projects are discussed. Moreover, the examples are re-interpreted in the light of the theoretical material. I argue that the choice of an optimal level of abstraction for the gene is vital for a successful genome analysis. Keywords: gene concept; scientific method; experimentalism; reductionism; anti-reductionism; data-mining 1. Introduction The gene is one of the most fundamental concepts in genetics (It is as important to biology, as the atom is to physics or the molecule to chemistry.). The concept was born with the Mendelian paradigm of heredity, and fundamentally influenced genetics over 150 years [1]. -

Mutation Breeding in Pepper S

XA0101052 INIS-XA--390 Mutation Breeding Review JOINT FAO/IAEA DIVISION OF ISOTOPE AND RADIATION APPLICATIONS OF ATOMIC ENERGY FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, VIENNA No. 4 March 1986 MUTATION BREEDING IN PEPPER S. DASKALOV* Plant Breeding Unit, Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Isotope and Radiation Applications of Atomic Energy for Food and Agricultural Development, Seibersdorf Laboratory, IAEA, Vienna Abstract Pepper (Capsicum sp, ) is an important vegetable and spice crop widely grown in tropical as well as in temperate regions. Until recently the improvement programmes were based mainly on using natural sources of germ plasm, crossbreeding and exploiting the heterosis of F hybrids. However, interest in using induced mutations is growing. A great number of agronomically useful mutants as well as mutants valuable for genetic, cytological and physiological studies have been induced and described. Acknowledgements: The author expresses his gratitude to Dr. A. Micke, Head, Plant Breeding and Genetics Section, FAO/IAEA Joint Division and to Dr. T. Hermelin, Head, Agriculture Laboratory, Joint FAO/IAEA Programme, Seibersdorf Laboratory, for their critical review of the manuscript and valuable contributions. * Permanent Address: Institute of Genetics, Sofia 1113, Bulgaria 32/ 22 In this review information is presented about suitable mutagen treatment procedures with radiation as well as chemicals, M effects, handling the treated material in M , M and subsequent generations, and mutant screening procedures. This is supplemented by a description of reported useful mutants and released cultivars. Finally, general advice is given on when and how to incorporate mutation induction in Capsicum improvement programmes. INTRODUCTION Peppers are important vegetable and spice crops widely grown in tropical as well as in temperate regions. -

SOHASKY-DISSERTATION-2017.Pdf (2.074Mb)

DIFFERENTIAL MINDS: MASS INTELLIGENCE TESTING AND RACE SCIENCE IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Kate E. Sohasky A dissertation submitted to the Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Baltimore, Maryland May 9, 2017 © Kate E. Sohasky All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Historians have argued that race science and eugenics retreated following their discrediting in the wake of the Second World War. Yet if race science and eugenics disappeared, how does one explain their sudden and unexpected reemergence in the form of the neohereditarian work of Arthur Jensen, Richard Herrnstein, and Charles Murray? This dissertation argues that race science and eugenics did not retreat following their discrediting. Rather, race science and eugenics adapted to changing political and social climes, at times entering into states of latency, throughout the twentieth century. The transnational history of mass intelligence testing in the twentieth century demonstrates the longevity of race science and eugenics long after their discrediting. Indeed, the tropes of race science and eugenics persist today in the modern I.Q. controversy, as the dissertation shows. By examining the history of mass intelligence testing in multiple nations, this dissertation presents narrative of the continuity of race science and eugenics throughout the twentieth century. Dissertation Committee: Advisors: Angus Burgin and Ronald G. Walters Readers: Louis Galambos, Nathaniel Comfort, and Adam Sheingate Alternates: François Furstenberg -

A Correlation of Cytological and Genetical Crossing-Over in Zea Mays. PNAS 17:492–497

A CORRELATION OF CYTOLOGICAL AND GENETICAL CROSSING-OVER IN ZEA MAYS HARRIET B. CREIGHTON BARBARA MCCLINTOCK Botany Department Cornell University Ithaca, New York Creighton, H., and McClintock, B. 1931 A correlation of cytological and genetical crossing-over in Zea mays. PNAS 17:492–497. E S P Electronic Scholarly Publishing http://www.esp.org Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project Foundations Series –– Classical Genetics Series Editor: Robert J. Robbins The ESP Foundations of Classical Genetics project has received support from the ELSI component of the United States Department of Energy Human Genome Project. ESP also welcomes help from volunteers and collaborators, who recommend works for publication, provide access to original materials, and assist with technical and production work. If you are interested in volunteering, or are otherwise interested in the project, contact the series editor: [email protected]. Bibliographical Note This ESP edition, first electronically published in 2003 and subsequently revised in 2018, is a newly typeset, unabridged version, based on the 1931 edition published by The National Academy of Sciences. Unless explicitly noted, all footnotes and endnotes are as they appeared in the original work. Some of the graphics have been redone for this electronic version. Production Credits Scanning of originals: ESP staff OCRing of originals: ESP staff Typesetting: ESP staff Proofreading/Copyediting: ESP staff Graphics work: ESP staff Copyfitting/Final production: ESP staff © 2003, 2018 Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project http://www.esp.org This electronic edition is made freely available for educational or scholarly purposes, provided that this copyright notice is included. The manuscript may not be reprinted or redistributed for commercial purposes without permission. -

Interpreting the History of Evolutionary Biology Through a Kuhnian Prism: Sense Or Nonsense?

Interpreting the History of Evolutionary Biology through a Kuhnian Prism: Sense or Nonsense? Koen B. Tanghe Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Lieven Pauwels Department of Criminology, Criminal Law and Social Law, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Alexis De Tiège Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Johan Braeckman Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Traditionally, Thomas S. Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) is largely identified with his analysis of the structure of scientific revo- lutions. Here, we contribute to a minority tradition in the Kuhn literature by interpreting the history of evolutionary biology through the prism of the entire historical developmental model of sciences that he elaborates in The Structure. This research not only reveals a certain match between this model and the history of evolutionary biology but, more importantly, also sheds new light on several episodes in that history, and particularly on the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), the construction of the modern evolutionary synthesis, the chronic discontent with it, and the latest expression of that discon- tent, called the extended evolutionary synthesis. Lastly, we also explain why this kind of analysis hasn’t been done before. We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive review, as well as the editor Alex Levine. Perspectives on Science 2021, vol. 29, no. 1 © 2021 by The Massachusetts Institute of Technology https://doi.org/10.1162/posc_a_00359 1 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/posc_a_00359 by guest on 30 September 2021 2 Evolutionary Biology through a Kuhnian Prism 1. -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

Mendelism, Plant Breeding and Experimental Cultures: Agriculture and the Development of Genetics in France Christophe Bonneuil

Mendelism, plant breeding and experimental cultures: Agriculture and the development of genetics in France Christophe Bonneuil To cite this version: Christophe Bonneuil. Mendelism, plant breeding and experimental cultures: Agriculture and the development of genetics in France. Journal of the History of Biology, Springer Verlag, 2006, vol. 39 (n° 2 (juill. 2006)), pp.281-308. hal-00175990 HAL Id: hal-00175990 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00175990 Submitted on 3 Oct 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Mendelism, plant breeding and experimental cultures: Agriculture and the development of genetics in France Christophe Bonneuil Centre Koyré d’Histoire des Sciences et des Techniques, CNRS, Paris and INRA-TSV 57 rue Cuvier. MNHN. 75005 Paris. France Journal of the History of Biology, vol. 39, no. 2 (juill. 2006), 281-308. This is an early version; please refer to the original publication for quotations, photos, and original pagination Abstract The article reevaluates the reception of Mendelism in France, and more generally considers the complex relationship between Mendelism and plant breeding in the first half on the twentieth century. It shows on the one side that agricultural research and higher education institutions have played a key role in the development and institutionalization of genetics in France, whereas university biologists remained reluctant to accept this approach on heredity. -

Mi Científica Favorita 2

MI CIENTÍFICA FAVORITA 2 GOBIERNO MINISTERIO GOBIERNO MINISTERIO GOBIERNO MINISTERIO DE ESPAÑA DE CIENCIA, INNOVACIÓN DE ESPAÑA DE CIENCIA, INNOVACIÓN DE ESPAÑA DE CIENCIA, INNOVACIÓN Y UNIVERSIDADES Y UNIVERSIDADES Y UNIVERSIDADES MI CIENTÍFICA FAVORITA 2 FAVORITA MI CIENTÍFICA MI CIENTÍFICA FAVORITA 2 MI CIENTÍFICA FAVORITA 2 Instituto de Ciencias Matemáticas (CSIC, UAM, UC3M, UCM) GOBIERNO MINISTERIO DE ESPAÑA DE CIENCIA, INNOVACIÓN Y UNIVERSIDADES Índice 07 Presentación 08 Agnodice 10 María Sibylla Merian 12 Emilie du Châtelet 14 Mary Anning 16 Sofia Kovalevskaya 20 Hertha Ayrton 22 Nettie Stevens 24 Henrietta Swan Leavitt 26 Mileva Maric´ 28 Lise Meitner 34 Emmy Noether 36 Inge Lehmann 38 Janaki Ammal 40 Grace Hopper 42 Rachel Carson 44 Rita Levi-Montalcini 46 Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin 50 Chien-Shiung Wu 52 Ángeles Alvariño 54 Jane Cooke Wright 56 Stephanie Kwolek 58 Inmaculada Paz Andrade 60 Gabriela Morreale 64 Valentina Tereshkova 66 Lynn Margulis 70 María del Carmen Maroto Vela 72 Wangari Maathai Matemáticas 74 Françoise Barré-Sinoussi Física 76 Ingrid Daubechies Química Biología 80 Ameenah Gurib-Fakim Ciencias de la Tierra 82 Lisa Randall Medicina 84 Begoña Vila Ingeniería e informática 86 Sara Zahedi Nota: 89 Glosario de términos Ciertas fechas se desconocen, por ello no aparecen indicadas en las líneas de tiempo. 92 Fuentes INTRODUCCIÓN Las mujeres han contribuido al desarrollo de la ciencia a lo largo de toda la historia aunque, en muchas ocasiones, su trabajo no ha sido reconocido como se merecía. En este libro presentamos la vida y obra de algunas de ellas, es- cogidas por estudiantes de 5º y 6º de primaria de centros educativos de toda España como sus científicas favoritas. -

Pho300007 Risk Modeling and Screening for Brcai

?4 101111111111 PHO300007 RISK MODELING AND SCREENING FOR BRCAI MUTATIONS AMONG FILIPINO BREAST CANCER PATIENTS by ALEJANDRO Q. NAT09 JR. A Master's Thesis Submitted to the National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology College of Science University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City As Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY March 2003 In memory of my gelovedmother Mrs. josefina Q -Vato who passedaway while waitingfor the accomplishment of this thesis... Thankyouvery inuchfor aff the tremendous rove andsupport during the beautifil'30yearstfiatyou were udth me... Wom, you are he greatest! I fi)ve you very much! .And.. in memory of 4 collaborating 6reast cancerpatients who passedaway during te course of this study ... I e.Vress my deepest condolence to your (overtones... Tou have my heartfeligratitude! 'This tesis is dedicatedtoa(the 37 cofla6oratingpatients who aftruisticaffyjbinedthisstudyfor te sake offuture generations... iii This is to certify that this master's thesis entitled "Risk Modeling and Screening for BRCAI Mutations among Filipino Breast Cancer Patients" and submitted by Alejandro Q. Nato, Jr. to fulfill part of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology was successfully defended and approved on 28 March 2003. VIRGINIA D. M Ph.D. Thesis Ad RIO SUSA B. TANAEL JR., M.Sc., M.D. Thesis Co-.A. r Thesis Reader The National Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology endorses acceptance of this master's thesis as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. -

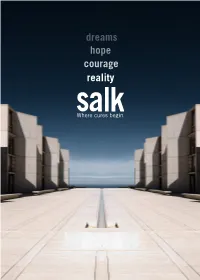

Dreams Hope Courage Reality Table of Contents

dreams hope courage reality Table of Contents 1. About Salk 14. Key Contacts 3. The Salk Difference 15. Financial Overview 4. Scientific Priorities 16. Salk Leadership 6. Discoveries 17. Board of Trustees 8. Salk Scientists 18. Salk Architecture 10. Salk by the Numbers 20. Get to Know Us 11. Why I Support Salk... 21. Our Mission 12. Supporting Discoveries About Salk Jonas Salk changed the world. Inspired to rid civilization of polio, he used basic science to solve its mysteries and in the process helped alter the course of the 20th century along with the future of science, medicine and human health. Untold millions have benefited from his work. The Salk Institute was created to attract the best scientific minds in the world. We’ve built on his vision and have become the leading center for independent research, delving into the most serious biological questions of our time. Experts come from around the globe to work in open collaboration—conducting innovative and daring research, mapping discoveries and developing the blueprints so that cures can happen, anywhere in the world. Twelve Nobel laureates have called the Salk Institute home. 1 It’s this “critical mass of intellect,” which embraces the most modern technologies and prizes discovery over credit, that distinguishes Salk. And it results in some of the world’s most breathtaking findings, which advance our understanding of cancer, aging and the brain. These are the first steps that will lead to tomorrow’s cures for cancer, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, heart disease, metabolic diseases, ALS, schizophrenia, childhood development disorders and spinal cord injuries.