Public Art Policy the City of Mobile, Alabama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2020 Activity Guide

Fall 2020 Activity Guide MOBILE PARKS AND RECREATION WWW.CITYOFMOBILE.ORG/PARKS FALL @mobileparksandrec @mobileparksandrec 2020 FROM THE SENIOR DIRECTOR OF PARKS AND RECREATION Greetings, As I write this letter, six months into the COVID-19 pandemic, I think about all the changes we’ve had to endure to stay safe and healthy. The Parks and Recreation team has spent this time cleaning and organizing centers, creating new virtual and physical distancing activities, and most importantly continuing to provide meals to our seniors and youth. I would like to share many of the updates that happened in Parks and Recreation since March. • Special Events is now under the umbrella of Parks and Recreation. • Community Centers received new Gym floors, all floors were buffed and deep cleaned. Staff handmade protective face masks for employees, and over 28,123 meals were distributed to children ages 0-18. • Azalea City Golf Course staff cleaned and sanitized clubhouse, aerated greens, driving range, trees and fairways, completed irrigation upgrade project funded by Alabama Trust Fund Grant, contractor installed 45’ section of curb in parking lot and parking lot was restriped, painted fire lane in front of clubhouse, painted tee markers & fairway yardage markers and cleaned 80 golf carts. • Tennis Centers staff patched and resurfaced 6 Tennis courts, 118 light poles were painted, 9.5 miles of chain link fence was painted around 26 Tennis courts, 3 storage sheds were painted, 15 picnic tables were painted, 8 sets of bleachers were painted & park benches, 14 white canopy frames were painted plus 28 trash bins, court assignment board painted & 26 umpire chairs assembled. -

130643653012924000 Lagniap

2 | LAGNIAPPE | January 1, 2015 - January 7, 2015 LAGNIAPPE ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• WEEKLY January 1, 2015 – January 7, 2015 | www.lagniappemobile.com Ashley Trice BAY BRIEFS Co-publisher/Editor Beneficiaries of county lodging tax [email protected] proceeds have shifted from initial recipients. Rob Holbert Co-publisher/Managing Editor 5 [email protected] Steve Hall COMMENTARY Marketing/Sales Director 2015 promises to be a big year for the Port [email protected] City. Gabriel Tynes Assistant Managing Editor 8 [email protected] Dale Liesch BUSINESS Reporter Baldwin County surpasses Shelby as [email protected] the fastest growing in the state. Jason Johnson Reporter 14 [email protected] Alyson Stokes CUISINE Web & Social Media Manager/Reporter [email protected] Fine wine and food Kevin Lee CONTENTS pairings at a low-key, Associate Editor/Arts Editor West Mobile hideout. [email protected] Andy MacDonald Cuisine Editor [email protected] Stephen Centanni Music Editor [email protected] J. Mark Bryant Sports Writer 15 [email protected] Daniel Anderson Chief Photographer COVER [email protected] The Mobile Housing Laura Rasmussen Board’s $750 million Art Director redevelopment plan may www.laurarasmussen.com 20 change the perception Brooke Mathis Advertising Sales Executive of public housing. [email protected] Beth Williams Advertising Sales Executive [email protected] Misty Groh Advertising Sales Executive [email protected] -

Winter Spring 2020

Winter-SpringWinter-Spring GuideGuide 20202020 MOBILE PARKS AND RECREATION WINTER WWW.CITYOFMOBILE.ORG/PARKS SPRING @mobileparks @mobileparksandrec 2020 FROM THE SENIOR DIRECTOR OF PARKS AND RECREATION Welcome to another great year of Parks and Recreation programming! The momentum continues and I am excited about the work we have done in one year and what we will provide. We have accomplished so much in the past year including refreshing the look of the brochure, implementing the programmatic partnership that brought on 14 new programs, introducing the Movies in the Park Series, and our fi rst Halloween Extravaganza. The Executive Team will continue to visit and host community meetings to get your feedback and ideas about parks and recreation services. We have key positions coming in 2020 to enhance programming, extend community center hours, and increase park services. Look for more family and community events like the Movie and Music in the Park and the Musical Shrek performance. Thank you to everyone who has been participating with MPRD over the years and welcome to the many new individuals and families that are becoming more aware of the sites and services that we off er. I request that you say something if you see something in our parks. Your calls and feedback makes us aware of what is happening in the parks so we can be responsive at (251) 208-1600. We are here to ensure your experience in our spaces is of the highest quality. Yours in Service, Shonnda Smith Senior Director of Parks and Recreation MAYOR, CITY OF MOBILE William S. -

January 23, 2012 MOBILE COUNTY COMMISSION the Mobile County

January 23, 2012 MOBILE COUNTY COMMISSION The Mobile County Commission met in regular session in the Government Plaza Auditorium, in the City of Mobile, Alabama, on Monday, January 23, 2012, at 10:00 A. M. The following members of the Commission were present: Connie Hudson, President, Merceria Ludgood and Mike Dean, Members. Also present were John F. Pafenbach, County Administrator/Clerk of the Commission, Jay Ross, County Attorney, and Joe W. Ruffer, County Engineer. President Hudson chaired the meeting. __________________________________________________ INVOCATION The invocation was given by Commissioner Merceria Ludgood. __________________________________________________ President Hudson called for a moment of silent prayer for two (2) victims who lost their lives in a tornado in the Birmingham, Alabama area earlier this morning, which have also affected communities in Chilton and Monroe Counties, Alabama. __________________________________________________ PRESENT RESOLUTION/PROCLAIM JANUARY 27, 2012 AS EARNED INCOME TAX CREDIT (EITC) AWARENESS DAY President Hudson presented a resolution to the following members of nonprofit organizations: Diana Brinson, HandsOn South Alabama Raymond Huff, Internal Revenue Service Lanny Wilson, Goodwill Industries/Easter Seals of the Gulf Coast, Inc. Patsy Herron, United Way of Southwest Alabama Terri Grodsky, Retired Senior Volunteer Program President Hudson said tax preparation assistance helps low to moderate income families, the disabled, elderly and limited English proficiency individuals to take advantage of federal tax benefits such as, earned income tax credit, child tax credit and receive up to $5,751.00 in tax refunds which is a substantial financial benefit for families struggling to make ends meet. She said in 2011 local nonprofit organizations and numerous volunteers operated sixteen (16) tax sites within Mobile County that have helped 1,738 families claim over $2 million in tax refunds and credits. -

Mobile Cruising Guide

Alabama State Docks Historic Districts GM & O Building/ DoWntoWn MoBiLE ArEa WAVE Transit Church Street East Transportation Center DeTonti Square INFORMATION 165 Lower Dauphin CRUISE TERMINAL Oakleigh Garden moda! ROUTE Old Dauphin Way t e Dr Ma treet rti S n Historic Districts Stre Luth e ermoda! King JrSTOPS OutsiDE oF DoWntoWn﹕ rine ett y Avenu Africatown athe e Ashland Place Lafa C Look for the moda! stop umbrellas. N N Campground For moda! Information, call Leinkauf (251) 344-6600. To view, please visit www.mobilehd.org/maps.html Business Improvement District U.S. Post Oce Within this district, please call their 32 41 hotline 327-SAFE for information, 46 Dr Ma MOBILE RIVER vehicle assistance rtin coMPLEtE or safety escort services. Luth er King Jr Bay Bridge Road Avenu PARKS/GREEN e SPACES cruisEr’sSt Stephens Road P PARKING 40 6 Arthur R. Outlaw Mobile GuiDE 41 Convention Center 4 30 P 49 15 16 10 2 head 38 50 Bank P 52 P Tunnel 6 1 46 31 40 17 8 35 3 10 25 27 18 9 29 10 27 18 3 31 34 27 33 13 22 Gov’t 11 Plaza A e d eet eet eet dsco r r r reet t R t Av d S S St te St nn 15 et A 35 Dunlap Dr eorgia P ay N f G 7 36 14 22 N 28 N La N Monterey N Catherine 28 47 Ben May 43 24 Mobile 19 Public Library 26B Alabama Cruise Terminal 30 5 13 21 P OAKLEIGH AREA e t enu ee r Av 8 Monterey Place Brown Street Brown Str t eet S Ann St t Visit Mobile Georgia tree ee S r 26B Welcome Center e S rey St ine Street e her I-10, Exit 26B t S Lafayett 26A S Mont S Ca Ride the moda! Downtown Transportation • Follow to 48 Transportation is available from the Fort of Colonial Mobile • Water St. -

Mchd 2018 Annual Reportmchd.Orgfamilyhealthalabama.Org from the Health Officer

MMCHDCHD 22018018 AANNUALNNUAL RREPORTEPORT MMCHD.ORGCHD.ORGFFAMILYHEALTHALABAMA.ORGAMILYHEALTHALABAMA.ORG TABLE OF CONTENTS BOARD OF HEALTH Dr. Barbara Mitchell FROM THE HEALTH OFFICER Chairman SERVICE REPORT Dr. C.M.A. “Max” Rogers, IV APPENDIX Secretary ORGANIZATIONAL CHART Dr. D. Lawrence Bedsole FINANCIAL STATEMENT Member Dr. Matthew E. Cepeda Member Dr. Nina Ford Johnson Member Dr. William O. Richards Member The Honorable Merceria Ludgood President, Mobile County Commission 01.01.18 to 03.11.18 A HEALTHY, SAFE, PREPARED AND The Honorable Connie Hudson EDUCATED COMMUNITY President, Mobile County Commission On the cover: Services provided at the Southwest Mobile Health Center include 03.12.18 to 12.31.18 pediatric, adult health, family planning, immunizations, lab, dental and X-ray. With the onboarding of a new full-time dentist in 2018, the center was able to expand patient access to dental care within this Medically Underserved Area. 1 MCHD 2018 ANNUAL REPORTMCHD.ORGFAMILYHEALTHALABAMA.ORG FROM THE HEALTH OFFICER This past year was an- cent in seven states while it is at least 30 percent in 29 other impressive one for other states. Alabama ranks fi h in the charts with 36.3 MCHD and Family Health. percent of its adults having a Body Mass Index of 30 or Despite having to deal greater. with Tropical Storm Gor- don during the Joint Obesity can lead to many medical condi ons such as Commission visit, our heart disease, stroke, diabetes and certain types of can- Joint Commission ac- cer. This is why MCHD has declared war on physical credita on was renewed inac vity. -

Accommodations Guide

OFFICIAL 2018-19 ACCOMMODATIONS�GUIDE 800.5.MOBILE | 251.208.2000 WWW.MOBILE.ORG ABOUT THIS GUIDE Welcome home! Whether you are returning to Mobile aft er a long absence to reconnect with friends and family, here on business or visiting our city for the very fi rst time, we want you to feel right at home. This guide is designed to showcase our variety of accommodation choices, from four-diamond and family-owned bed and breakfasts to rate- friendly and extended stay. We’re sure you’ll fi nd the most amazing place to sett le in as you begin exploring Mobile. Inside Downtown Area .......................................... 4-8 Uptown Shopping District .......................9-10 I-65 Corridor North ..................................10-16 I-10 West Area ..........................................17-19 Cruising from Mobile .............................. 20-21 Conventions, Groups & Gatherings ......22-23 Dauphin Island .........................................24-26 Eastern Shore ..........................................27-29 Gulf Shores/Orange Beach .........................28 Campgrounds ..........................................30-31 Save the Date ...............................................32 Area Maps ............................................... 34-39 Visit Mobile Welcome Center Published by Compass Media LLC compassmedia.com On the cover: Mobile skyline, ATD/Chris Granger; Berney Fly Bed & Breakfast; The Battle House Renaissance Mobile Hotel & Spa; The Admiral Hotel Mobile, Curio Collection by Hilton Other select images by Tad Denson/MyShotz.com All businesses in Mobile, unless otherwise indicated. Rates and services are subject to change without notice. 0418_17250 Mobile skyline COME STAY A WHILE We celebrate our vibrant 300-year history by sharing lots of stories and long-standing traditions with natives and visitors alike. Once called the Paris of the South, Mobile has long been the cultural center of the Gulf Coast, and you’ll fi nd an authentic experience like nowhere else in the southern United States. -

DECEMBER 2016 • Volume 16:Issue 04 Inside…

THE ARTS, ENTERTAINMENT & EMPOWERMENT GUIDE OF THE GULF COAST DECEMBER 2016 • Volume 16:Issue 04 INSIDE… COVER STORY 38 Special/New Years Eve 05 EVENTS/ENTERTAINMENT R. Kelly 15 PASSINGS Gwen Ifill 17 GOODBYE 2016 Events Calendar ..........................15 FREE Passings ..........................................17 TAKE ONE Laughter ..........................................19 ABOUT STEPPIn’ OUT... CONtriBUtorS... STEPPIN’ OUT is a subsidiary of LEGACY 166 Inc., a non-profit organization with A.D. McKinley Featured Article: a Mission to provide Educational, Career, and Economic opportunities for Youth THE ReAL ENEMY - THE INNER Me and the Underserved of Diverse Cultures; make available Cultural Activities for community participation; and deliver Quality of Life Skills Training through Arthur Mack the Arts and Community Collaborations. Featured Article: ThInkIng OuTsIde The Gold Wrapping Paper STEPPIN’ OUT provides quality of Of The BOx Once upon a time, there was a man who worked very hard just to keep life information to the community each food on the table for his family. This particular year a few days before month at no cost to the reader. Even Dr. Barbara Walker Christmas, he punished his little five-year-old daughter after learning though STEPPIN’ OUT is not a “hard Featured Article: that she had used up the family’s only roll of expensive gold wrapping news’ publication, the columns submitted Ask dR. walkeR paper. by our contributors touch on subjects As money was tight, he became even more upset when on Christmas that address a wide range of community Eve he saw that the child had used all of the expensive gold paper to and cultural issues. -

Chresal Threadgill

Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce DEC. 2018-JAN. 2019 the MCPSS’s Superintendent Chresal Threadgill $58 M Storage Facility Announced Mobile Chamber Names Manufacturer & Innovator of the Year the business view DECEMBER 2018/JANUARY 2019 1 The first full-stack managed solutions provider. Consider IT managed. The new C Spire Business is the nation’s first ever to combine advanced connectivity with cloud, software, hardware, communications, and professional services to create a single, seamless, managed IT service portfolio. The result is smarter. Faster. More secure. From desktop to data center, we step in wherever you need us and take on your biggest technology challenges. You focus on business. cspire.com/business | 855.CSPIRE2 ©2018 C Spire. All rights reserved. 2 the business view DECEMBER 2018/JANUARY 2019 the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce DEC. 2018-JAN. 2019 | In this issue ON THE COVER Chresal Threadgill is the new superintendent for Mobile County Public Schools. His focus is on From the Publisher - Bill Sisson continuous improvement in education. See story on pg. 10. Photo by FusionPoint Media. Lessons Learned in Toulouse, France 4 News You Can Use This year the Mobile Area Obviously, Airbus has a Chamber’s Leaders Exchange huge economic impact on that 6 Kimberly-Clark Named was a very special one. For only region of France, but so does Manufacturer of the Year the second time in the more higher education. It was mind- 7 McFadden Engineering Receives than 30 years of city-to-city boggling to learn about the Innovator of the Year exchanges, our Chamber more than 100,000 students 9 Small Business of the Month: leadership traveled to an living there, attending some of 2 international destination. -

Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for Fiscal

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGES I. INTRODUCTORY SECTION Transmittal Letter i – x GFOA Certificate of Achievement xi Organization Chart xii List of Principal Officials xiii Map of City xiv II. FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditor's Report 1 – 2 A. MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS 3 – 17 B. BASIC FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Government-wide Financial Statements Statement of Net Position 18 Statement of Activities 19 – 20 Fund Financial Statements Governmental Fund Financial Statements Balance Sheet 21 Reconciliation of the Balance Sheet to the Statement of Net Position 22 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances 23 Reconciliation of the Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances to the Statement of Activities 24 Proprietary Fund Financial Statements Statement of Net Position 25 – 26 Statement of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Net Position 27 – 28 Statement of Cash Flows 29 – 30 Component Units Financial Statements Statement of Net Position 31 Statement of Activities 32 – 33 Notes to the Financial Statements 34 – 105 C. REQUIRED SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION OTHER THAN MD&A General Fund - Schedule of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances - Budget and Actual 106 – 108 Notes to General Fund - Schedule of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balance - Budget and Actual 109 Schedule of Changes in the Net Pension Liability and Related Ratios – Employees’ Retirement System of Alabama 110 Schedule of Employer Contributions – Employees’ Retirement System of Alabama 111 Schedule of Changes in the Net Pension Liability and Related Ratios – Police and Firefighters Retirement Plan 112 Schedule of Employer Contributions – Police and Firefighters Retirement Plan 113 Schedule of Changes in the Net Pension Liability and Related Ratios – Transit Workers Pension Plan 114 Schedule of Employer Contributions – Transit Workers Pension Plan 115 – 116 Schedule of Changes in Total OPEB Liability and Related Ratios 117 D. -

2021 Summer Guide

SUMMER 2021 Activity Guide ! Discover YourWWW.CITYOFMOBILE.ORG/PARKS Parks @MobileParksAndRec FROM THE SENIOR DIRECTOR OF PARKS AND RECREATION Greetings This has been a tough and challenging year for everyone. As we transition to summer after a full year of Safer-at-Home order, Parks and Recreation has created family friendly physical distancing activities. We will continue to provide virtual programming and classes on You Tube and FaceBook for those who prefer to be at home. Please see below for a few of the highlights I’m excited about this summer: • Special Events is now under Parks and Recreation Events and we are revamping and enhancing past events like Art Walk and the July 4th activities and creating new events such as Roll Mobile, Tour de Mobile-Food Trucks and Kites Over Mobile (pg. 50) • MPRD Youth Summer Camps at five community centers: Dotch, Hillsdale, Seals, Sullivan, and Rickarby (pg. 9) • NEW! Teen Center at Newhouse (pg. 29) • Therapeutic Programs hosting- Reel Fun Fishing (pg. 42) • Seniors Drive-thru Bingo (pg. 45) • Tennis Lessons (pg. 46) • Golf 2021 Mobile Metro Championship (pg. 17) Don’t miss out on these great activities that are happening in your city! Thank you for allowing us to serve you, Shonnda Smith Senior Director of Parks and Recreation VISION: MISSION: CORE VALUES: Fun and Safe Places where To increase the Social, Emotional • Customer Service Everybody is Somebody and Physical well-being of • Teamwork our community by providing • Diversity diverse activities in secure and welcoming spaces. 2 MASKS ARE ENCOURAGED FOR ALL INDOOR ACTIVITIES & EVENTS Help your community by volunteering with Parks and Recreation! • Tutoring • Senior Activities For more information • Athletics • And many more! please contact us: Whatever your skills or schedule, (251) 208-1605 you can volunteer! [email protected] 3 MAYOR, CITY OF MOBILE William S. -

Tree Commission Minutes June 21, 2016

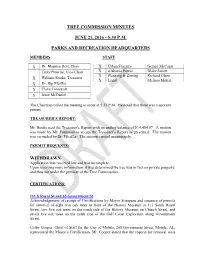

TREE COMMISSION MINUTES JUNE 21, 2016 - 5:30 P.M. PARKS AND RECREATION HEADQUARTERS MEMBERS STAFF X Dr. Maurice Holt, Chair X Urban Forestry Gerard McCants Terry Plauche, Vice-Chair X Alabama Power Blake Jarrett X Planning & Zoning Richard Olsen William Rooks, Treasurer X X Legal Melissa Mutert X Dr. Rip Pfeiffer X Cleve Formwalt X Jesse McDaniel The Chairman called the meeting to order at 5:31 P.M. He noted that there was a quorum present. TREASURER’S REPORT: Mr. Rooks read the Treasurer’s Report with an ending balance of $14,454.57. A motion was made by Mr. Formwalt to accept the Treasurer’s Report as presented. The motion was seconded by Dr. Pfieiffer. The motion carried unanimously. PERMIT REQUESTS: WITHDRAWN Application was received late and was incomplete. Upon receiving more information, it was determined the tree was in fact on private property, and thus not under the purview of the Tree Commission. CERTIFICATIONS: 111 S Royal St and 65 Government St Acknowledgement of receipt of Certifications by Mayor Stimpson and issuance of permits for removal of eight live oak trees in front of the History Museum at 111 South Royal Street, two live oak trees on the south side of the History Museum on Church Street, and seven live oak trees on the north side of the Gulf Coast Exploreum along Government Street. Colby Cooper, Chief of Staff for the City of Mobile, 205 Government Street, Mobile, AL, represented the Mayor’s Certification. Mr. Cooper stated that the request for removal wass Mobile Tree Commission Minutes June 21, 2016 PAGE 2 necessary because the trees were damaging the sidewalks causing a safety hazard for those using the sidewalks as well as damaging utility infrastructure located underneath the sidewalks.