Identifying Fitness and Optimal Life-History Strategies for an Asexual Filamentous Fungus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hidden Kingdom

INTRODUCTION Fungi—The Hidden Kingdom OBJECTIVE • To provide students with basic knowledge about fungi Activity 0.1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION The following text provides an introduction to the fungi. It is written with the intention of sparking curiosity about this GRADES fascinating biological kingdom. 4-6 with a K-3 adaptation TEACHER INSTRUCTIONS TYPE OF ACTIVITY 1. With your class, brainstorm everything you know about fungi. Teacher read/comprehension 2. For younger students, hand out the question sheet before you begin the teacher read and have them follow along and MATERIALS answer the questions as you read. • copies of page 11 3. For older students, inform them that they will be given a • pencils brainteaser quiz (that is not for evaluation) after you finish reading the text. VOCABULARY 4. The class can work on the questions with partners or in groups bioremediation and then go over the answers as a class. Discuss any chitin particularly interesting facts and encourage further fungi independent research. habitat hyphae K-3 ADAPTATION kingdom 1. To introduce younger students to fungi, you can make a KWL lichens chart either as a class or individually. A KWL chart is divided moulds into three parts. The first tells what a student KNOWS (K) mushrooms about a subject before it is studied in class. The second part mycelium tells what the student WANTS (W) to know about that subject. mycorrhizas The third part tells what the child LEARNED (L) after studying nematodes that subject. parasitic fungi 2. Share some of the fascinating fungal facts presented in the photosynthesis “Fungi—The Hidden Kingdom” text with your students. -

Fungal Evolution: Major Ecological Adaptations and Evolutionary Transitions

Biol. Rev. (2019), pp. 000–000. 1 doi: 10.1111/brv.12510 Fungal evolution: major ecological adaptations and evolutionary transitions Miguel A. Naranjo-Ortiz1 and Toni Gabaldon´ 1,2,3∗ 1Department of Genomics and Bioinformatics, Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, Dr. Aiguader 88, Barcelona 08003, Spain 2 Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08003 Barcelona, Spain 3ICREA, Pg. Lluís Companys 23, 08010 Barcelona, Spain ABSTRACT Fungi are a highly diverse group of heterotrophic eukaryotes characterized by the absence of phagotrophy and the presence of a chitinous cell wall. While unicellular fungi are far from rare, part of the evolutionary success of the group resides in their ability to grow indefinitely as a cylindrical multinucleated cell (hypha). Armed with these morphological traits and with an extremely high metabolical diversity, fungi have conquered numerous ecological niches and have shaped a whole world of interactions with other living organisms. Herein we survey the main evolutionary and ecological processes that have guided fungal diversity. We will first review the ecology and evolution of the zoosporic lineages and the process of terrestrialization, as one of the major evolutionary transitions in this kingdom. Several plausible scenarios have been proposed for fungal terrestralization and we here propose a new scenario, which considers icy environments as a transitory niche between water and emerged land. We then focus on exploring the main ecological relationships of Fungi with other organisms (other fungi, protozoans, animals and plants), as well as the origin of adaptations to certain specialized ecological niches within the group (lichens, black fungi and yeasts). -

Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions

United States Department of Field Guide to Agriculture Common Macrofungi Forest Service in Eastern Forests Northern Research Station and Their Ecosystem General Technical Report NRS-79 Functions Michael E. Ostry Neil A. Anderson Joseph G. O’Brien Cover Photos Front: Morel, Morchella esculenta. Photo by Neil A. Anderson, University of Minnesota. Back: Bear’s Head Tooth, Hericium coralloides. Photo by Michael E. Ostry, U.S. Forest Service. The Authors MICHAEL E. OSTRY, research plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, St. Paul, MN NEIL A. ANDERSON, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology, St. Paul, MN JOSEPH G. O’BRIEN, plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, St. Paul, MN Manuscript received for publication 23 April 2010 Published by: For additional copies: U.S. FOREST SERVICE U.S. Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 April 2011 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/ CONTENTS Introduction: About this Guide 1 Mushroom Basics 2 Aspen-Birch Ecosystem Mycorrhizal On the ground associated with tree roots Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria 8 Destroying Angel Amanita virosa, A. verna, A. bisporigera 9 The Omnipresent Laccaria Laccaria bicolor 10 Aspen Bolete Leccinum aurantiacum, L. insigne 11 Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum 12 Saprophytic Litter and Wood Decay On wood Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus populinus (P. ostreatus) 13 Artist’s Conk Ganoderma applanatum -

Perithecial Ascomycetes from the 400 Million Year Old Rhynie Chert: an Example of Ancestral Polymorphism

Mycologia, 97(1), 2005, pp. 269±285. q 2005 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 Perithecial ascomycetes from the 400 million year old Rhynie chert: an example of ancestral polymorphism Editor's note: Unfortunately, the plates for this article published in the December 2004 issue of Mycologia 96(6):1403±1419 were misprinted. This contribution includes the description of a new genus and a new species. The name of a new taxon of fossil plants must be accompanied by an illustration or ®gure showing the essential characters (ICBN, Art. 38.1). This requirement was not met in the previous printing, and as a result we are publishing the entire paper again to correct the error. We apologize to the authors. T.N. Taylor1 terpreted as the anamorph of the fungus. Conidioge- Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and nesis is thallic, basipetal and probably of the holoar- Natural History Museum and Biodiversity Research thric-type; arthrospores are cube-shaped. Some peri- Center, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas thecia contain mycoparasites in the form of hyphae 66045 and thick-walled spores of various sizes. The structure H. Hass and morphology of the fossil fungus is compared H. Kerp with modern ascomycetes that produce perithecial as- Forschungsstelle fuÈr PalaÈobotanik, Westfalische cocarps, and characters that de®ne the fungus are Wilhelms-UniversitaÈt MuÈnster, Germany considered in the context of ascomycete phylogeny. M. Krings Key words: anamorph, arthrospores, ascomycete, Bayerische Staatssammlung fuÈr PalaÈontologie und ascospores, conidia, fossil fungi, Lower Devonian, my- Geologie, Richard-Wagner-Straûe 10, 80333 MuÈnchen, coparasite, perithecium, Rhynie chert, teleomorph Germany R.T. -

Protists/Fungi Station Lab Information

Protists/Fungi Station Lab Information 1 Protists Information Background: Perhaps the most strikingly diverse group of organisms on Earth is that of the Protists, Found almost anywhere there is water – from puddles to sediments. Protists rely on water. Somea re marine (salt water), some are freshwater, some are terrestrial (land dwellers) in moist soil and some are parasites which live in the tissues of others. The Protist kingdom is made up of a wide variety of eukaryotic cells. All protist cells have nuclei and other characteristics eukaryotic features. Some protists have more than one nucleus and are called “multinucleated”. Cellular Organization: Protists show a variety in cellular organization: single celled (unicellular), groups of single cells living together in a close and permanent association (colonies or filaments) or many cells = multicellular organization (ex. Seaweed). Obtaining food: There is a variety in how protists get their food. Like plants, many protists are autotrophs, meaning they make their own food through photosynthesis and store it as starch. It is estimated that green protist cells chemically capture and process over a billion tons of carbon in the Earth’s oceans and freshwater ponds every year. Photosynthetic or “green” protists have a multitude of membrane-enclosed bags (chloroplasts) which contain the photosynthetic green pigment called chlorophyll. Many of these organisms’ cell walls are similar to that of plant cells and are made of cellulose. Others are “heterotrophs”. Like animals, they eat other organisms or, like fungi, receiving their nourishment from absorbing nutrient molecules from their surroundings or digest living things. Some are parasitic and feed off of a living host. -

Biology of Fungi, Lecture 2: the Diversity of Fungi and Fungus-Like Organisms

Biology of Fungi, Lecture 2: The Diversity of Fungi and Fungus-Like Organisms Terms You Should Understand u ‘Fungus’ (pl., fungi) is a taxonomic term and does not refer to morphology u ‘Mold’ is a morphological term referring to a filamentous (multicellular) condition u ‘Mildew’ is a term that refers to a particular type of mold u ‘Yeast’ is a morphological term referring to a unicellular condition Special Lecture Notes on Fungal Taxonomy u Fungal taxonomy is constantly in flux u Not one taxonomic scheme will be agreed upon by all mycologists u Classical fungal taxonomy was based primarily upon morphological features u Contemporary fungal taxonomy is based upon phylogenetic relationships Fungi in a Broad Sense u Mycologists have traditionally studied a diverse number of organisms, many not true fungi, but fungal-like in their appearance, physiology, or life style u At one point, these fungal-like microbes included the Actinomycetes, due to their filamentous growth patterns, but today are known as Gram-positive bacteria u The types of organisms mycologists have traditionally studied are now divided based upon phylogenetic relationships u These relationships are: Q Kingdom Fungi - true fungi Q Kingdom Straminipila - “water molds” Q Kingdom Mycetozoa - “slime molds” u Kingdom Fungi (Mycota) Q Phylum: Chytridiomycota Q Phylum: Zygomycota Q Phylum: Glomeromycota Q Phylum: Ascomycota Q Phylum: Basidiomycota Q Form-Phylum: Deuteromycota (Fungi Imperfecti) Page 1 of 16 Biology of Fungi Lecture 2: Diversity of Fungi u Kingdom Straminiplia (Chromista) -

9B Taxonomy to Genus

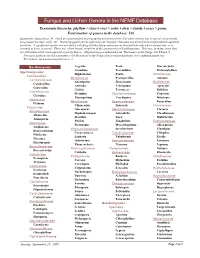

Fungus and Lichen Genera in the NEMF Database Taxonomic hierarchy: phyllum > class (-etes) > order (-ales) > family (-ceae) > genus. Total number of genera in the database: 526 Anamorphic fungi (see p. 4), which are disseminated by propagules not formed from cells where meiosis has occurred, are presently not grouped by class, order, etc. Most propagules can be referred to as "conidia," but some are derived from unspecialized vegetative mycelium. A significant number are correlated with fungal states that produce spores derived from cells where meiosis has, or is assumed to have, occurred. These are, where known, members of the ascomycetes or basidiomycetes. However, in many cases, they are still undescribed, unrecognized or poorly known. (Explanation paraphrased from "Dictionary of the Fungi, 9th Edition.") Principal authority for this taxonomy is the Dictionary of the Fungi and its online database, www.indexfungorum.org. For lichens, see Lecanoromycetes on p. 3. Basidiomycota Aegerita Poria Macrolepiota Grandinia Poronidulus Melanophyllum Agaricomycetes Hyphoderma Postia Amanitaceae Cantharellales Meripilaceae Pycnoporellus Amanita Cantharellaceae Abortiporus Skeletocutis Bolbitiaceae Cantharellus Antrodia Trichaptum Agrocybe Craterellus Grifola Tyromyces Bolbitius Clavulinaceae Meripilus Sistotremataceae Conocybe Clavulina Physisporinus Trechispora Hebeloma Hydnaceae Meruliaceae Sparassidaceae Panaeolina Hydnum Climacodon Sparassis Clavariaceae Polyporales Gloeoporus Steccherinaceae Clavaria Albatrellaceae Hyphodermopsis Antrodiella -

727-735 Issn 2077-4613

Middle East Journal of Applied Volume : 08 | Issue :03 |July-Sept.| 2018 Sciences Pages: 727-735 ISSN 2077-4613 Antifungal bio-efficacy of the red algae Gracilaria confervoides extracts against three pathogenic fungi of cucumber plant Amira Sh. Soliman1, A.Y. Ahmed2, Siham E. Abdel-Ghafour2, Mostafa M. El-Sheekh3 and Hassan M. Sobhy1 1Natural Resources Department, Institute of African Research and Studies, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt. 2Plant Pathology Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt. 3Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt. Received: 07 May 2018 / Accepted: 26 June 2018 / Publication date: 15 July 2018 ABSTRACT In this study, the potential of the macroalgae Gracilaria confervoides red algae extracts and powder were evaluated as a bioagent source of the three soil-borne pathogenic fungi of cucumber namely; Rhizoctonia solani, Fusarium solani and Macrophomina phaseolina in Egypt. Five organic solvents; Ethyl acetate, Methanol, Acetone, Benzene, and Chloroform, in addition to water were used for the extraction to evaluate their bioeffecinecy on mycelium growth reduction of the three fungal pathogens on potato dextrose agar (PDA). Radial growth reduction of the pathogens was noticed in R. solani and F. solani with all solvents and water extraction. In case of the fungus M. phaseolinae all solvents and water extractions malformatted the fungal growth (aerial mycelium and no microsclerotia). The highest reduction (100%) obtained on R. solani when chloroform extraction was used followed by ethyl acetate extraction (50%). In the greenhouse experiment, macroalgae powder was used to evaluate its effect on disease incidence which indicated about (70%) decrease for diseases. The highest total yield (133.2g) was obtained from plants infected with M. -

The Genetics of Life History Traits in the Fungus Neurospora Crassa

The Genetics of Life History Traits in the Fungus Neurospora crassa The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Zimmerman, Kolea. 2016. The Genetics of Life History Traits in the Fungus Neurospora crassa. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493574 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Genetics of Life History Traits in the Fungus Neurospora crassa A dissertation presented by Kolea Zimmerman to The Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Biology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 Copyright Notice This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Advisor: Anne Pringle Author: Kolea Zimmerman The Genetics of Life History Traits in the Fungus Neurospora crassa Abstract The study of life histories is fundamental to understanding why some organisms live for a very short time while others live for a long time, why some produce thousands of offspring while others produce one, or why some need a mate to reproduce while others can do it on their own. -

BIOL 1030 – TOPIC 3 LECTURE NOTES Topic 3: Fungi (Kingdom Fungi – Ch

BIOL 1030 – TOPIC 3 LECTURE NOTES Topic 3: Fungi (Kingdom Fungi – Ch. 31) KINGDOM FUNGI A. General characteristics • Fungi are diverse and widespread. • Ten thousand species of fungi have been described, but it is estimated that there are actually up to 1.5 million species of fungi. • Fungi play an important role in ecosystems, decomposing dead organisms, fallen leaves, feces, and other organic materials. °This decomposition recycles vital chemical elements back to the environment in forms other organisms can assimilate. • Most plants depend on mutualistic fungi to help their roots absorb minerals and water from the soil. • Humans have cultivated fungi for centuries for food, to produce antibiotics and other drugs, to make bread rise, and to ferment beer and wine • Fungi play ecological diverse roles - they are decomposers (saprobes), parasites, and mutualistic symbionts. °Saprobic fungi absorb nutrients from nonliving organisms. °Parasitic fungi absorb nutrients from the cells of living hosts. .Some parasitic fungi, including some that infect humans and plants, are pathogenic. .Fungi cause 80% of plant diseases. °Mutualistic fungi also absorb nutrients from a host organism, but they reciprocate with functions that benefit their partner in some way. • Fungi are a monophyletic group, and all fungi share certain key characteristics. B. Morphology of Fungi 1. heterotrophs - digest food with secreted enzymes “exoenzymes” (external digestion) 2. have cell walls made of chitin 3. most are multicellular, with slender filamentous units called hyphae (Label the diagram below – Use Textbook figure 31.3) 1 of 11 BIOL 1030 – TOPIC 3 LECTURE NOTES Septate hyphae Coenocytic hyphae hyphae may be divided into cells by crosswalls called septa; typically, cytoplasm flows through septa • hyphae can form specialized structures for things such as feeding, and even for food capture 4. -

Sanchytriaceae, Fungi Incertae Sedis) Confirms Its Close Relationship to Amoeboradix Sergey Karpov, Andrey Vishnyakov, David Moreira, Purificacion Lopez-Garcia

The Ultrastructure of Sanchytrium tribonematis (Sanchytriaceae, Fungi incertae sedis) Confirms its Close Relationship to Amoeboradix Sergey Karpov, Andrey Vishnyakov, David Moreira, Purificacion Lopez-Garcia To cite this version: Sergey Karpov, Andrey Vishnyakov, David Moreira, Purificacion Lopez-Garcia. The Ultrastructure of Sanchytrium tribonematis (Sanchytriaceae, Fungi incertae sedis) Confirms its Close Relationship to Amoeboradix. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, Wiley, 2019, 10.1111/jeu.12740. hal-02365842 HAL Id: hal-02365842 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02365842 Submitted on 15 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Ultrastructure of Sanchytrium tribonematis (Sanchytriaceae, Fungi incertae sedis) Confirms its Close Relationship to Amoeboradix Sergey A. Karpova,b,c , Andrey E. Vishnyakovb, David Moreirac & Purificación López- Garcíac a Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg 199034, Russia b St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg 199034, Russia c Unité d’Ecologie, Systématique -

A New Hysteriform Dothideomycete (Gloniaceae, Pleosporomycetidae Incertae Sedis), Purpurepithecium Murisporum Gen. Et Sp. Nov. O

Cryptogamie, Mycologie, 2017, 38 (2): 241-251 © 2017 Adac. Tous droits réservés Anew hysteriform dothideomycete (Gloniaceae, Pleosporomycetidae incertae sedis), Purpurepithecium murisporum gen. et sp. nov. on pine cone scales Subashini C. JAYASIRI a,b,Kevin D. HYDE b,c,E.B. Gareth JONES d, Hiran A. ARIYAWANSAE, Ali H. BAHKALI f, Abdallah M. ELGORBAN f &Ji-Chuan KANG a* aEngineering Research Center of Southwest Bio-Pharmaceutical Resources, Ministry of Education, Guizhou University,Guiyang 550025, Guizhou Province, China bCenter of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai 57100, Thailand cWorld Agroforestry CentreEast and Central Asia Office, 132 Lanhei Road, Kunming 650201, China dNantgaredig, 33B St. Edwards Road, Southsea, Hants. PO5 3DH, UK eDepartment of Plant Pathology and Microbiology,College of BioResources and Agriculture, National Taiwan University,No.1, Sec.4, Roosevelt Road, Taipei 106, Taiwan, ROC fDepartment of Botany and Microbiology,College of Science, King Saud University,P.O.Box: 2455, Riyadh, 1145, Saudi Arabia Abstract –The family Gloniaceae is represented by the genera Glonium (plant saprobes) and Cenococcum (ectomycorrhizae). This work adds to the knowledge of the family,byintroducing anew taxon from dead scales of pine cones collectedonthe ground in Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. Analysis of acombined LSU, SSU, RPB2 and TEF1 sequence dataset matrix placed it in Gloniaceaeand Purpurepithecium murisporum gen. et sp. nov.isintroduced to accommodate the new taxon. The genus is characterized by erumpent to superficial, navicular hysterothecia, with aprominent longitudinal slit, branched pseudoparaphyses in agel matrix, with apurple pigmented epithecium, hyaline to dark brown muriform ascospores and a Psiloglonium stygium-like asexual morph which is produced in culture.