1 Curriculum Unit Patterns of Islamization.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

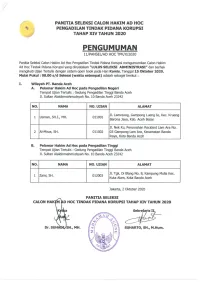

PENGUMUMAN Ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020

PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC PENGADILAN TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 PENGUMUMAN ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020 Panitia Seleksi Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Pengadilan Tindak Pidana Korupsi mengumumkan Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Tindak Pidana Korupsi yang dinyatakan "LULUS SELEKSI ADMINISTRASI" dan berhak mengikuti Ujian Tertulis dengan sistem open book pada Hari Kamis, Tanggal 15 Oktober 2020, Mulai Pukul : 08.00 s/d Selesai (waktu setempat) adalah sebagai berikut : I. Wilayah PT. Banda Aceh A. Pelamar Hakim Ad Hoc pada Pengadilan Negeri Tempat Ujian Tertulis : Gedung Pengadilan Tinggi Banda Aceh Jl. Sultan Alaidinmahmudsyah No. 10 Banda Aceh 23242 NO. NAMA NO. UJIAN ALAMAT Jl. Lamreung, Gampong Lueng Ie, Kec. Krueng 1 Usman, SH.I., MH. 011001 Barona Jaya, Kab. Aceh Besar Jl. Nek Ku, Perumahan Recident Lam Ara No. 2 Al-Mirza, SH. 011002 03 Gampong Lam Ara, Kecamatan Banda Raya, Kota Banda Aceh B. Pelamar Hakim Ad Hoc pada Pengadilan Tinggi Tempat Ujian Tertulis : Gedung Pengadilan Tinggi Banda Aceh Jl. Sultan Alaidinmahmudsyah No. 10 Banda Aceh 23242 NO. NAMA NO. UJIAN ALAMAT Jl. Tgk. Di Blang No. 8, Kampung Mulia Kec. 1 Zaini, SH. 012003 Kuta Alam, Kota Banda Aceh Jakarta, 2 Oktober 2020 PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 Dr. SUHA SUHARTO, SH., M.Hum. PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC PENGADILAN TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 PENGUMUMAN ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020 Panitia Seleksi Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Pengadilan Tindak Pidana Korupsi mengumumkan Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Tindak Pidana Korupsi yang dinyatakan "LULUS SELEKSI ADMINISTRASI" dan berhak mengikuti Ujian Tertulis dengan sistem open book pada Hari Kamis, Tanggal 15 Oktober 2020, Mulai Pukul : 08.00 s/d Selesai (waktu setempat) adalah sebagai berikut : II. -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

Pemaknaan Inskripsi Pada Kompleks Makam Islam Kuno Katangka Di Kabupaten Gowa

PEMAKNAAN INSKRIPSI PADA KOMPLEKS MAKAM ISLAM KUNO KATANGKA DI KABUPATEN GOWA The Meaning Inskription of Mausoleum Ancient in Katangka Complex Regency of Gowa ROSMAWATI P1900206007 PROGRAM PASCASARJANA UNIVERSITAS HASANUDDIN MAKASSAR 2008 T E S I S PEMAKNAAN INSKRIPSI PADA KOMPLEKS MAKAM ISLAM KUNO KATANGKA DI KABUPATEN GOWA ROSMAWATI P1900206007 KONSENTRASI ILMU SEJARAH PROGRAM STUDI ANTROPOLOGI PASCASARJANA UNIVERSITAS HASANUDDIN ii 2008 PENGESAHAN TESIS PEMAKNAAN INSKRIPSI PADA KOMPLEKS MAKAM ISLAM KUNO KATANGKA DI KABUPATEN GOWA Disusun dan Diajukan oleh ROSMAWATI P1900206007 Program Studi Antropologi Konsentrasi Ilmu Sejarah Menyetujui Komisi Pembimbing Dr. A. Rasyid Asba, MA. Dr. Anwar Thosibo, M.Hum Ketua Anggota Mengetahui Ketua Program Studi Antroplogi Dr. H. Machmud Tang, MA. iii ABSTRACT ROSMAWATI. The Meaning Inscription of Moesleum Ancient of Katangka Complext in Regency of Gowa (guided by A. Rasyid Asba and Anwar Thosibo) This research aim to explain history growt of Islam in Makassar, specially meaning of inscription at ancient mausoleum in Katangka Complex. In that bearing, was explained about socialization of Islam in social and politic pranata. Explained also form and obstetrical style of inscription and also its meaning. All that aim to know on adaptation of pattern between local culture and Islam. Clarification for this research problem use the method of history research with approach of history-archaeology. Its procedure cover the step of source gathering (heuristic), source verification, interpretation and historiography. Result of this research show that Islam growth in Makassar show the existence of acculturation between Islam influence and local cultural. Found inscription of mausoleum that used letter of Arab with Arab Ianguage and Makassar Ianguage (Ukir Serang). -

Keberagamaan Orang Jawa Dalam Pandangan Clifford Geertz Dan Mark R

Shoni Rahmatullah Amrozi 2fI: 10.35719/fenomena.v20i1.46 KEBERAGAMAAN ORANG JAWA DALAM PANDANGAN CLIFFORD GEERTZ DAN MARK R. WOODWARD Shoni Rahmatullah Amrozi Institut Agama Islam Negeri (IAIN) Jember [email protected] Abstrak: Artikel ini membahas perbedaan pandangan Clifford Geertz dan Mark R. Woodward tentang keberagamaan orang Jawa. Kedua pandangan ini menjadi rujukan bagi para intelektual yang men- dalami kajian tentang agama (Islam) di masyarakat Jawa. Geertz mengkategorikan kelompok agama dalam masyarakat Jawa (Abangan, Santri, dan Priyayi) berdasarkan penelitiannya di Mo- jokuto (Pare, Kediri, Jawa Timur). Sementara itu, Mark R. Woodward meneliti keberagamaan orang Jawa di Yogyakarta. Woodward menganggap Yogyakarta sebagai pusat budaya masyarakat Jawa dan dianggap mampu mengkolaborasikan Islam dan budaya lokal. Artikel ini menyimpulkan bahwa Geertz menilai bahwa keberagamaan orang Jawa terkait dengan ketaatan dan ketidaktaa- tan. Sementara itu, Woodward melihat keberagamanan ini sebagai salah satu bentuk tafsir ter- hadap Islam oleh masyarakat Jawa.. Kata Kunci: Islam Jawa, Abangan, santri, priyai Abstract: This article examines the different views of Clifford Geertz and Mark R. Woodward about Javanese religiousness. Both of their studies, even today, have become references for intellectuals who study religion (Islam) in Javanese society. Geertz categorized the religious groups in Javanese society (Abangan, Santri, and Priyayi). Geertz's (the 1950s) view have based on his research in Modjokuto (Pare, Kediri, East Java). Meanwhile, Mark R. Wood- ward researched Javanese religiousness in Yogyakarta (the 1980s). Woodward observed Yogyakarta as the cultur- al centre of Javanese society. It is considered capable of collaborating between Islam and local culture. The article concludes that Geertz assessed that Javanese religiousness was related to religious obedience and disobedience. -

Participatory Poverty Assessment in West Java and South Sulawesi

Final Report Participatory Poverty Assessment In West Java and South Sulawesi Volume 2: Site Reports of Twelve Villages in West Java and South Sulawesi Submitted to: For Waseda University By: Yayasan Inovasi Pemerintahan Daerah November 2009 Research Team Alit Merthayasa, PhD – Project Manager Dr. Kabul Sarwoto – Technical Manager Novi Anggriani, MA – Survey Manager Herry Widjanarko B.Y. – Supervisor, West Java Alma Arief – Supervisor, South Sulawesi West Java Facilitators: Jayabakti – Bekasi & Pasir Jambu - Purwakarta Herry Widjanarko B.Y. Andrey Achmad Pratama Nissa Cita Adinia Nanggerang – Bogor & Sukanegara - Cianjur Firkan Maulana F. Ronald R. Sendjaja Anna Nur Rahmawaty Gegesikkulon – Cirebon & Neglasari – Bandung Kartawi Lutfi Purnama Ida Dewi Yuliawati Padasuka – Tasikmalaya & Lengkong Jaya – Garut Asep Kurniawan Permana Endang Turyana South Sulawesi Facilitator: Manjangloe - Jeneponto & Raya - Maros Alma Arief Saleh Yasin Harwan Andi Kunna Batunilamung - Bulukumba & Kalegowa - Gowa Nasthain Gasba Budie Ichwanuddin Suaib Hamid i FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGMENT Final Report for Participatory Poverty Assessment (PPA) in West Java and South Sulawesi was written to report and document the result of field research on assessment of poverty based on the poor community them selves that were conducted in October 2009. The reports consist of two volumes, namely Volume 1 and Volume 2. They are prepared by a team led by Dr. Kabul Sarwoto (Technical Manager) and Novi Anggriani, MA (Survey Manager) under supervision of Alit Merthayasa, PhD (Project Manager). The writer team includes Herry Widjanarko and Alma Arief. Other field research team members are Firkan Maulana, Kartawi, Asep Kurniawan, Nasthain Gasba, Ronald Sendjaja, Anna Nur Rahmawaty, Andrey A Pratama, Nissa C Adinia, Permana, Endang Turyana, Ida D Yuliawati, Lutfi Purnama, Suaib Hamid, Budie Ichwanuddin, Saleh Yasin and Harwan A Kunna. -

From Custom to Pancasila and Back to Adat Naples

1 Secularization of religion in Indonesia: From Custom to Pancasila and back to adat Stephen C. Headley (CNRS) [Version 3 Nov., 2008] Introduction: Why would anyone want to promote or accept a move to normalization of religion? Why are village rituals considered superstition while Islam is not? What is dangerous about such cultic diversity? These are the basic questions which we are asking in this paper. After independence in 1949, the standardization of religion in the Republic of Indonesia was animated by a preoccupation with “unity in diversity”. All citizens were to be monotheists, for monotheism reflected more perfectly the unity of the new republic than did the great variety of cosmologies deployed in the animistic cults. Initially the legal term secularization in European countries (i.e., England and France circa 1600-1800) meant confiscations of church property. Only later in sociology of religion did the word secularization come to designate lesser attendance to church services. It also involved a deep shift in the epistemological framework. It redefined what it meant to be a person (Milbank, 1990). Anthropology in societies where religion and the state are separate is very different than an anthropology where the rulers and the religion agree about man’s destiny. This means that in each distinct cultural secularization will take a different form depending on the anthropology conveyed by its historically dominant religion expression. For example, the French republic has no cosmology referring to heaven and earth; its genealogical amnesia concerning the Christian origins of the Merovingian and Carolingian kingdoms is deliberate for, the universality of the values of the republic were to liberate its citizens from public obedience to Catholicism. -

SUSTAINING SYNERGY, SPREADING ENERGY Themes

Sustainability Report 2018 2018 SUSTAINING SYNERGY, SPREADING ENERGY THEMES SUSTAINING SYNERGY, SPREADING ENERGY PT Pertamina (Persero) has a vital Strengthening synergy has become responsibility to fulfill the demand of energy increasingly meaningful considering the vast in Indonesia. In fact, the demand of energy, areas Pertamina must serve, some of which both fuel oil and gas, continues to increase are difficult to reach because they are in the in line with the increasing population and 3T (frontier, outermost and least developed) vehicles in this country. In order to perform regions and remote areas. Specifically for such responsibility as outstandingly as these regions, Pertamina has been assigned possible, the Company is committed to to distribute fuel through the One-Price Fuel strengthen and maintain the synergy that Program. As a responsible corporation, the has been built, either the synergy amongst Company is strongly committed to making its units, subsidiaries, and amongst SOEs. the assignment successfull. Until the end of 2018, Pertamina has achieved the target set by the government so that the distribution of energy is more evenly distributed and reaches out to all corners of the country. Laporan Keberlanjutan 2018 2 PT Pertamina(Persero) SUSTAINING SYNERGY, SPREADING ENERGY 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Economic Performance Company Profile Environmental Performance Corporate Governance Social Performance 2 Themes 12 About this Sustainability Report 4 Table of Contents 14 Process to Define Report Topics 6 Sustainability -

List of Images (All Photos by R. Michael Feener Or Anna M. Gade)

List of Images (All photos by R. Michael Feener or Anna M. Gade) Figure 1. A popular poster depicting imagined portraits of the Wali Songo, the 'Nine saints,' to whom the Islamization of Java is traditionally attributed. Figure 2. Men visiting the tomb of Sunang Sonang, one of the Wali Songo. The blue and white porcelain decorating the walls around the cemetery is a reminder of trade routes connecting China and Western Asia; this trade network was highly influential in the historical process of Indonesian Islamization. Figure 3. The Mosque of Bayan Beleq in Northern Lombok. This recently-restored mosque has long been considered one of the primary seats of this island's indigenized interpretation of Islamic culture. Figure 4. Float of a 'Bugis Schooner' representing the South Sulawesi team in the parade opening the MTQ National Contest for the Recitation of the Qur'an (Jambi, Sumatra, 1997). Inscribed on the boat in both Bugis and Roman script is a motto which translates as, "We pledge our unity." Figure 5. Royal heirlooms held by descendants of the last Sultan at the Balai Kuning (Yellow Hall) in Sumbawa Sesar (central Indonesia). Many of these items demonstrate the kinds of luxury goods traded in the Archipelago in earlier centuries of maritime history; they also represent symbolic elements drawing upon a wide range of Sumbawan, Indic, and Islamicate conceptions of power and authority. Figure 6. Batik cloth from Jambi, Sumatra (nineteenth century?), decorated with bird motifs and the Name of God ('Allah') in Arabic. Figure 7. A Muslim bride and groom at their wedding in East Java (1991). -

Nyuwun Slamet; Local Wisdom of Javanese Rural People in Dealing with Covid-19 Pandemic Through Request in Slametan Rite

Javanologi – Vol. IV No. 2 June 2021 Nyuwun Slamet; Local Wisdom of Javanese Rural People in Dealing With Covid-19 Pandemic Through Request in Slametan Rite Mukhlas Alkaf1, Andrik Purwasito2, I Nyoman Murtana3, Wakit Abdullah4 1, 2, 4(Sebelas Maret University) 3( Indonesian Institut of the Art Surakarta) Abstract Covid-19 pandemic effect has resulted in restlessness within community. Some are restless because of decreased job and business opportunities, fear of being infected with disease, fear of losing the closed and beloved one, etc. This article tries to raise a Javanese community’s local wisdom, Slametan. Slametan is a form of local wisdom existing within Javanese people containing an action functioning to be a medium to request God to give safety. In principle, slametan rite is one of human actions to communicate with the Creator. Through the rite, human beings feel that what they ask will be granted. Human beings doing this are also sure and suggested that those having done the rite will get safety and protection effect. This belief will further create self confidence and the feeling of secure among them in working and continuing the life. Keywords: Covid, slametan, rite, safety. A. Introduction In early 2020, all people in the world were shocked by a deadly disease induced by virus. The virus is called Corona or Covid-19. This virus is dangerous as it leads to death, respiratory function impairment, and makes the patients developing organ dysfunction in their lifetime. More dangerously, this virus can be transmitted very easily through physical contact between human beings who have contact or are close to each other. -

Indonesian Journal of Social Sciences Volume 4, Nomer 1, Cultural

Indonesian Journal of Social Sciences Volume 4, nomer 1, Cultural System of Cirebonese People: Tradition of Maulidan in the Kanoman Kraton Sistem Budaya Masyarakat Cirebon: Tradisi Maulidan dalam Kraton Kanoman Deny Hamdani1 UIN Syarif Hidayatullah, Jakarta Abstract This paper examines the construction of Maulidan ritual in the commemoration of Prophet Muhammad’s birth at the Kanoman’s palace (kraton) Cirebon. Although the central element of the maulid is the veneration of Prophet, the tradition of Maulidan in Kanoman reinforced the religious authority of Sultan in mobilizing a massive traditional gathering by converging Islamic propagation with the art performance. It argues that the slametan (ritual meal with Arabic prayers), pelal alit (preliminary celebration), ‘panjang jimat’ (allegorical festival), asyrakalan (recitation of the book of maulid) and the gamelan sekaten can be understood as ‘indexical symbols’ modifying ‘trans-cultural Muslim ritual’ into local entity and empowering the traditional machinery of sexual division of ritual labour. The study focuses on the trend of Muslim monarch in the elaboration of maulid performance to demonstrate their piety and power in order to gain their legitimacy. Its finding suggests that religion tends to be shaped by society rather than society is shaped by religion. I emphasize that the maulidan tradition is ‘capable of creating meaningful connections between the imperial cult and every segment of ‘Cirebon people’ other than those Islamic modernists and Islamists who against it in principle. Based on the literature, media reports and interview materials, I argue that the meaning of rites may extend far beyond its stated purpose of venerating the Prophet since the folk religion has strategically generated the “old power” and religious authority. -

Democratic Culture and Muslim Political Participation in Post-Suharto Indonesia

RELIGIOUS DEMOCRATS: DEMOCRATIC CULTURE AND MUSLIM POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN POST-SUHARTO INDONESIA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science at The Ohio State University by Saiful Mujani, MA ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor R. William Liddle, Adviser Professor Bradley M. Richardson Professor Goldie Shabad ___________________________ Adviser Department of Political Science ABSTRACT Most theories about the negative relationship between Islam and democracy rely on an interpretation of the Islamic political tradition. More positive accounts are also anchored in the same tradition, interpreted in a different way. While some scholarship relies on more empirical observation and analysis, there is no single work which systematically demonstrates the relationship between Islam and democracy. This study is an attempt to fill this gap by defining Islam empirically in terms of several components and democracy in terms of the components of democratic culture— social capital, political tolerance, political engagement, political trust, and support for the democratic system—and political participation. The theories which assert that Islam is inimical to democracy are tested by examining the extent to which the Islamic and democratic components are negatively associated. Indonesia was selected for this research as it is the most populous Muslim country in the world, with considerable variation among Muslims in belief and practice. Two national mass surveys were conducted in 2001 and 2002. This study found that Islam defined by two sets of rituals, the networks of Islamic civic engagement, Islamic social identity, and Islamist political orientations (Islamism) does not have a negative association with the components of democracy. -

Indonesia 12

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Indonesia Sumatra Kalimantan p509 p606 Sulawesi Maluku p659 p420 Papua p464 Java p58 Nusa Tenggara p320 Bali p212 David Eimer, Paul Harding, Ashley Harrell, Trent Holden, Mark Johanson, MaSovaida Morgan, Jenny Walker, Ray Bartlett, Loren Bell, Jade Bremner, Stuart Butler, Sofia Levin, Virginia Maxwell PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Indonesia . 6 JAVA . 58 Malang . 184 Indonesia Map . 8 Jakarta . 62 Around Malang . 189 Purwodadi . 190 Indonesia’s Top 20 . 10 Thousand Islands . 85 West Java . 86 Gunung Arjuna-Lalijiwo Need to Know . 20 Reserve . 190 Banten . 86 Gunung Penanggungan . 191 First Time Indonesia . 22 Merak . 88 Batu . 191 What’s New . 24 Carita . 88 South-Coast Beaches . 192 Labuan . 89 If You Like . 25 Blitar . 193 Ujung Kulon Month by Month . 27 National Park . 89 Panataran . 193 Pacitan . 194 Itineraries . 30 Bogor . 91 Around Bogor . 95 Watu Karang . 195 Outdoor Adventures . 36 Cimaja . 96 Probolinggo . 195 Travel with Children . 52 Cibodas . 97 Gunung Bromo & Bromo-Tengger-Semeru Regions at a Glance . 55 Gede Pangrango National Park . 197 National Park . 97 Bondowoso . 201 Cianjur . 98 Ijen Plateau . 201 Bandung . 99 VANY BRANDS/SHUTTERSTOCK © BRANDS/SHUTTERSTOCK VANY Kalibaru . 204 North of Bandung . 105 Jember . 205 Ciwidey & Around . 105 Meru Betiri Bandung to National Park . 205 Pangandaran . 107 Alas Purwo Pangandaran . 108 National Park . 206 Around Pangandaran . 113 Banyuwangi . 209 Central Java . 115 Baluran National Park . 210 Wonosobo . 117 Dieng Plateau . 118 BALI . 212 Borobudur . 120 BARONG DANCE (P275), Kuta & Southwest BALI Yogyakarta . 124 Beaches . 222 South Coast . 142 Kuta & Legian . 222 Kaliurang & Kaliadem . 144 Seminyak .