PDF Watt Vs UKAD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page-1-20-June 11.Indd

Vol. 29 No. 3 June 2011 R New Floating Walkway To Be Built In Time For London Fortunes Of Olympics 2012 – See Page 3 President Obama Britain’s Super Rich Climb TTHEHE HHEADLINESEADLINES Scores Points By Cassandra Vinograd R UK To Provide Police THE FORTUNES of many Britain’s Uniforms To Libya’s Rebels wealthiest individuals appear to have BRITAIN will supply police offi cers in With PM turned. rebel-held eastern Libya with uniforms The 1,000 richest people in Britain and body armor, and help establish a increased their collective wealth by public radio station, Prime Minister Da- 18 percent in the past vid Cameron’s offi ce said last month. year and are now worth Following talks with Mustafa Abdul- £395.8bn, according to a Jalil, head of Libya’s National Transi- list published by the Sun- tional Council, Cameron said he had day Times newspaper. invited the rebels to open a permanent The newspaper was offi ce in London to cement contacts to later release its an- with Britain. nual rundown of Britain’s However, the UK has not followed Duke of 1,000 richest individuals Westminster France and Italy in recognizing the and families. council as Libya’s legitimate govern- Steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal’s family ment. members held onto their position as the “These steps continue our very clear wealthiest people in Britain with a fortune intention to work with the council to en- of £17.5bn – but they are 22 percent poorer sure Libya has a safe and stable future, than a year earlier thanks to a drop in the free from the tyranny of the Gadhafi share price of ArcelorMittal. -

Elmira College Information

Inside Elmira College Table of Contents Elmira College THE SCOOP ON Cover 1 ELMIRA COLLEGE Inside Elmira College 2 Information Sports Information 3 Location: Elmira College is a four-year, private, co 2011-12 Season Outlook 4 One Park Place -educational, liberal arts college with an undergraduate enrollment of 1,200. The Coaching Staff 5 Elmira, New York 14901 College is located in the Finger Lakes 2011-12 Player Profiles 6 (607) 735-1800 Region of Upstate New York. The average Founded: class size is 16, with a student to faculty 2011-12 Team Photo 13 ratio of 12:1. 1855 The College offers over thirty-five aca- 2011-12 Team Roster 14 Enrollment: demic majors, including: education, busi- 2010-11 Season in Review 15 ness, psychology, biology, nursing, pre- 1,200 medicine, pre-law, along with numerous 2010-11 Statistics 16 Colors: study abroad and internship programs. 2010-11 Inside the Numbers 17 Purple and Gold The Soaring Eagles sponsors ten varsity Nickname: women‘s teams in soccer, field hockey, Elmira in the ECAC West 18 volleyball, tennis, golf, basketball, cheer- Soaring Eagles leading, ice hockey, lacrosse and softball. EC Records 1973-2010 19 Affiliation: Men‘s varsity teams compete in soccer, golf, basketball, ice hockey, tennis and 100-Point Club 20 NCAA (Div. III), ECAC, lacrosse. Award Winners and Captains 21 Empire 8 Complementing the varsity sport offer- ings, are ten opportunities to participate EC Team Records 22 President: in junior varsity sports. Dr. Thomas K. Meier EC Single Game Leaders 23 Vice President of Athletics -

2020-21 Raiders Sponsor Pack

2020-21 Season Corporate Brochure RAIDERSCORPORATEBROCHURE NIHL2020/2021 SEASON place great methods and even greater plans to critics GB managed to stay in the group, and will return to the force they were before the old Romford again next year compete against the major hockey rink was demolished. nations, such as Canada, Sweden, Finland, Russia WHOARE THE RAIDERS? and the USA. Raiders also extend that working in the community to their charity efforts. Previous charities to whom The Romford rink is also used for training sessions The Raiders are a semi-professional ice hockey team the team made significant donations have included for the ITV Dancing on Ice series and last year’s that play in the newly formed NIHL National League. Breast Cancer Awareness, Autisim Now, St Francis sponsors were delighted to see their adverts The league season runs between mid September and Hospice, the local mental health awareness charity appearing on national TV as a result. early April each year. The season finale is the Havering Mind and for the upcoming season a local prestigious play offs in Coventry where the qualifying NHS charity to recognise their hard work throughout Raiders played the 2019-20 season in the brand new teams play semi finals and finals to become National the Covid-19 pandemic. top British League known as the National Ice Hockey Play-Off Champions. League where they mixed it with some of the There is no doubt that Ice Hockey is enjoying country’s major hockey towns from all over England The Raiders moved back to Romford in 2018 and into something of a renaissance in the UK. -

AB 133 J F 18 Editoral Pages.Indd

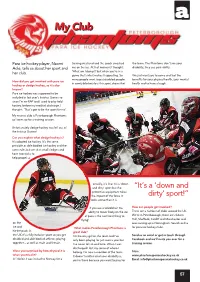

MyMy ClubClub Para ice hockey player, Naomi training weekend and the coach smashed the team. The Phantoms don’t see your Adie, tells us about her sport and me on the ice. At that moment I thought: disability, they see your ability. her club. ‘What am I doing?!’ but when you’re in a game that’s what makes it appealing. So We just want you to come and feel the many people want to put disabled people benefits for your physical health, your mental How did you get involved with para ice in comfy blankets but this sport shows that health and to have a laugh. hockey or sledge hockey, as it’s also known? Para ice hockey was supposed to be included in last year’s Invictus Games so since I’m ex-RAF and I used to play field hockey, before my medical discharge, I thought: ‘That’s got to be the sport for me’. My nearest club is Peterborough Phantoms so I went up for a training session. Unfortunately sledge hockey was left out of the Invictus Games! Can you explain what sledge hockey is? It’s adapted ice hockey. It’s the same principle as able bodied ice hockey and the same rules but we sit in small sledges and have two sticks to help propel us actually, it’s fine. It’s a ‘down and dirty’ sport but the “It’s a ‘down and protective equipment takes the impact of the force. It dirty’ sport!” looks worse than it is. If you use a wheelchair the How can people get involved? ability to move freely on the ice There are a number of clubs around the UK. -

English Ice Hockey Association

ENGLISH ICE HOCKEY ASSOCIATION RECREATIONAL SECTION 2010 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Sunday 12th September 2010 – 1pm At Jurys Inn Hotel Milton Keynes MINUTES Executive Committee: Tony Boynton [Chairman] Tony Wood, Linda Matthews, John Freeman. EIHA Representative: Alan Batcheldor. Team Representatives: Basingstoke Cougars, Black Bears, Bracknell B52’s, Bracknell Blizzard, Bradford Cannibals, British Army Blades, Chelmsford Chargers, Cleveland Comets, Coventry Chaos, Coventry Chargers, Flintshire Phantoms, Grimsby Lightning, Guildford Smoke, Medway Madness, Milton Keynes Hurricanes, Milton Keynes Jesters, Milton Keynes Rumble, Oxford Shooting Stars, Peterborough Eagles, Peterborough Phoenix, Peterborough Predators, RAF Bluewings, Royal Navy, Slough Scorpions, Slough Tornadoes, Solihull Vikings, Solihull Vipers, Streatham Nightwolves. Apologies received: Irene Jones, Ron Christison, Ritchie Clark, Altrincham Mustangs, Bristol Mad Dogs, Cardiff Ice Hounds, Whitley Wildcats, Cardiff Titans, Sheffield Blazers, Kingston Cobras, Blackburn Buccaneers, Durham Dragons, Nottingham Phantoms, Swindon Panthers, Newcastle Coyotes. Acceptance of last years Minutes Proposed by Chelmsford Chargers, seconded by MK Rumble. Passed unanimously. Chairman’s Report This section is running itself without many issues and we are getting people playing hockey. I have been involved with Rec. hockey for over 25 years; when we started with 4 teams, now we have 84 teams and that does not include the university teams! The good thing is, as far as I am concerned, is that we have liaised with Scotland. This has made it so much easier for teams to play in competitions across the Border; which has a lot to do with Tony Wood’s efforts in traveling to Scotland to discuss rules etc. This has made it easier for me; as in the past, I had to get clearance from the EIHA and Ice Hockey UK for you to play Scottish teams. -

Hull Pirates Program V1

C R E A T I N G A D V A N T A G E february edition 2020 OFFICIAL MATCHDAY MAGAZINE OF THE HULL PIRATES £3.00 #WEAREPIRATES WWW.HULLPIRATES.CO.UK coachs corner January has been a bit of a turning point for us, Its been nice to finally get some players back and start seeing the team at almost full strength for the first time this season, the results have followed alongside that and that’s a nice feeling and a positive one moving into the final stretch here. Looking forward I’m hoping we can overturn the 2 goal deficit in the come this coming week the first leg was quite a frustrating night but I certainly don’t think we’re out of it and will give it everything we have to turn it around! It’s been a tough season so far mainly down to injuries but credit to the boys in the room through everything we are still in a decent position, and a massive part of that is our home form which is also down to you guys the fans, we love the atmosphere here in hull and long may that continue! Hewy WWW.HULLPIRATES.CO.UK hull pirates PRESENTATIONS MATCHNIGHT SPONSOR NEEDLERS PIRATES 4 LIGHTING 3 V PUCK DROP 50-50 WINNER MOTM SOB WINNER WWW.HULLPIRATES.CO.UK PATCHS CAVE Q: Why don’t pirates shower before they walk the plank? A: Because they’ll just wash up on shore later. Q: Why is pirating so addictive? A: They say once ye lose yer first hand, ye get hooked! Q: How did the pirate get his Jolly Roger so cheaply? A: He bought it on sail. -

English Ice Hockey Association

ENGLISH ICE HOCKEY ASSOCIATION RECREATIONAL SECTION 2009 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Sunday 13 September 2009 At The Derbyshire Hotel, South Normanton 12.30pm MINUTES Executive Committee Tony Boynton [Chairman], Linda Matthews, Tony Wood. Team Representatives: Altrincham Aardvarx, Army Air Corps Ice Hawks, Basingstoke Cougars, Black Bears, Blackburn Buccaneers, Blackburn Falcons, Bracknell B52’s, Bracknell Blizzard, British Army Blades, Chelmsford Chargers, Cleveland Comets, Coventry Chaos, Coventry Chargers, Durham City Dragons, Flintshire Phantoms, Grimsby Lightning, Guildford Smoke, HMPS Tornadoes, Kingston Cobras, Medway Madness, Met Police, MK Hurricanes, MK Jesters, MK Rumble, Newcastle Coyotes, Newcastle Preditors, Nottingham Knights, Peterborough Eagles, Peterborough Phoenix, RAF Bluewings, RAF Cosford Stars, RAF Eastern Crusade, RN Destroyers, Sheffield Squeelers, Sheffield Vipers, Slough Satans, Slough Scorpions, Slough Tornadoes, Steel City Shoguns. Opening Remarks The Chairman opened the meeting by thanking everyone that attended and remarking that he was pleased at the large turn out. Apologies from Solihull Wolves, Bristol Warriors, Whitley Wildcats, Solent Scorpions, Nationwide Knights and Steve Tysoe. Also, apologies from Ron Christison, John Freeman and Richie Clark from the Executive. Acceptance of last years Minutes. Mr Waugh of MK Jesters told the Chairman that there was a mistake in last years minutes regarding the ban for the third offence. After the amendment, it was proposed by Peterborough Eagles and seconded by Kingston Cobras that the minutes of the 2008 AGM were accepted. Chairman’s Report We are here to try to make it easy for you to play hockey, you are the ones who do all the running around for your teams. We have 84 teams, started 26 years ago when we had just 5 teams. -

Fabulous Fabus

S E P T . 2 0 1 9 | I S S U E 2 PIRATE NEWS An official publication of the University of El Dorado 1 6 S E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 9 W E E K 3 8 FABULOUS A R T I C L E S I N S I D E : REVIEW OF MK FRIENDLIES FABUS LOOKING AHEAD TO THE Hull's star import settles into the start of the season START OF THE LEAGUE SEASON LOYALTY PARTNER NEWS FEATURED SPONSOR: HEB PIRATES' NEW WEBSITE GAME REVIEW H U L L P I R A T E S V M I L T O N K E Y N E S L I G H T N I N G The 'Phoney season' is over and with a 100% Sunday 15th saw MK travel to Yorkshire. This record from four friendly fixtures, Smailes time, Lightning proved more dogged. In a Goldie Hull Pirates can at least be confident gritty display, they restricted the Pirates to that they have prepared as well as any rivals just three goals in a tight, and sometimes to meet the challenges ahead. disjointed game but narrowly lost 3-2. This weekend's double bill against MK After weeks of conditioning training and Lightning, resembled the proverbial game of harder than expected warm-up games, the two halves. On Saturday 14th, MK hosted the Pirates looked a little jaded with some of the Pirates and were disappointed to be soundly players admitting that they are feeling the beaten 7-2 . -

MARCH Edition 1 2020 OFFICIAL MATCHDAY Fortnightly MAGAZINE of the HULL PIRATES £3.00

C R E A T I N G A D V A N T A G E MARCH edition 1 2020 OFFICIAL MATCHDAY fortnightly MAGAZINE OF THE HULL PIRATES £3.00 #WEAREPIRATES WWW.HULLPIRATES.CO.UK coachs corner Hi Everyone. Its tough to write these when things arent going so well results wise. I just think it sounds like excuses. Recently we’ve not quite been ourselves, making a few too many mistakes and it seems as every mistake we make at the moment just gets punished. The simple fact is we have to nd away out of it and we will. We just have to work a little smarter. The hustle is always there just sometimes you can work too hard and just end up going round in circles. Despite the result i think Sunday may have been what we needed. It was physical and at times a dirty game. Every guy on our team stood in and backed each other up. That in itself is the only way we get out of this......Together! JASON HEWITT So i ask you. PLAYER SPONSOR Stick with us, get behind the boys and well get back to the hockey and results we are used to ASAP! Hewy WWW.HULLPIRATES.CO.UK hull pirates MATCHNIGHT SPONSOR V PIRATES 7 TIGERS 5 WIN PUCK DROP 50-50 WINNER MOTM SOB WINNER WWW.HULLPIRATES.CO.UK PATCHS CAVE what is a pirates favorite study subject? ....arrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrt. What do you call a pirate that skips class? Captain Hooky! where do pirates like to eat? .... the HARRRRRRD rock cafe! How do pirates prefer to communicate? Aye to aye! What kind of grades does a pirate get in school? High seas! patch has been to a pet shop and got a friend. -

Feb Edition 2 2020

C R E A T I N G A D V A N T A G E february edition 2 2020 OFFICIAL MATCHDAY fortnightly MAGAZINE OF THE HULL PIRATES £3.00 #WEAREPIRATES WWW.HULLPIRATES.CO.UK coachs corner It’s been a mixed couple of weeks here obviously with the results. In my eyes its unacceptable and even worse its completely our own doing. We had a huge character win against MK in over�me, everyone was flying and feeling good. Then 20 hours later in Sheffield we threw the game away and handed the 2 points to them. The manor in which we did that has snowballed and led to our last 2 defeats this weekend. Its frustra�ng as we were in a really good posi�on and playing good hockey. Then through our own doing put ourselves in a mid table ba�le. Its credit to the league this year as the results have shown. Its competa�ve which is what we all wanted. There are no guaranted wins. Every team has to ba�le for every win now, but s�ll with all respect to other teams we shouldn’t be in this ba�le. Its no one persons fault, we have a team i believe in and know can win. We have had more than our fair share of injuries this season and ba�led through. We have players back and need to get back on track, play our game and build to the playoffs. So its reset �me and gut check �me. Guys have and will be challenged and i believe we will get a posi�ve reac�on. -

Date Day F/O Home Visitors Comp 2/9/2018 Sun Telford Tigers Raiders 1 Chall 8/9/2018 Sat 18:30 Basingstoke Bison Peterborough Ph

Date Day F/O Home Visitors Comp 2/9/2018 Sun Telford Tigers Raiders 1 Chall 8/9/2018 Sat 18:30 Basingstoke Bison Peterborough Phantoms 1 Chall 8/9/2018 Sat 17:15 Raiders 1 Bracknell Bees Chall 8/9/2018 Sat 18:15 Swindon Wildcats 1 Streatham HC Chall 9/9/2018 Sun 18:00 Bracknell Bees Raiders 1 Chall 9/9/2018 Sun 17:30 Peterborough Phantoms 1 Basingstoke Bison Chall 9/9/2018 Sun 17:30 Streatham HC Swindon Wildcats 1 Chall 15/9/2018 Sat 18:30 Basingstoke Bison Sheffield Steeldogs NIHLAC 15/9/2018 Sat 18:00 Bracknell Bees Raiders 1 NIHLS1 15/9/2018 Sat 17:30 Streatham HC Milton Keynes Thunder NIHLS1 15/9/2018 Sat 18:15 Swindon Wildcats 1 Hull Pirates NIHLAC 15/9/2018 Sat Telford Tigers Peterborough Phantoms 1 NIHLAC 16/9/2018 Sun 17:15 Invicta Dynamos Bracknell Bees NIHLS1 16/9/2018 Sun Hull Pirates Swindon Wildcats 1 NIHLAC 16/9/2018 Sun 17:30 Peterborough Phantoms 1 Telford Tigers NIHLAC 16/9/2018 Sun 17:30 Raiders 1 Streatham HC NIHLS1 16/9/2018 Sun 17:30 Sheffield Steeldogs Basingstoke Bison NIHLAC 22/9/2018 Sat 18:30 Basingstoke Bison Hull Pirates NIHLAC 22/9/2018 Sat 19:00 Peterborough Phantoms 1 Raiders 1 NIHLS1 22/9/2018 Sat Sheffield Steeldogs Swindon Wildcats 1 NIHLAC 23/9/2018 Sun 18:00 Bracknell Bees Streatham HC NIHLS1 23/9/2018 Sun Hull Pirates Basingstoke Bison NIHLAC 23/9/2018 Sun 18:45 Milton Keynes Thunder Peterborough Phantoms 1 NIHLS1 23/9/2018 Sun 17:30 Raiders 1 Invicta Dynamos NIHLS1 23/9/2018 Sun 18:15 Swindon Wildcats 1 Sheffield Steeldogs NIHLAC 29/9/2018 Sat 18:30 Basingstoke Bison Raiders 1 NIHLS1 29/9/2018 Sat -

13/09/2019 Pirate News

S E P T . 2 0 2 0 | I S S U E 1 PIRATE NEWS An official publication of the University of El Dorado 1 3 S E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 9 DEJA VU AS A R T I C L E S I N S I D E : PHANTOMS AND PIRATES CONTINUE TO REVIEW OF PHANTOMS FRIENDLIES THRILL by Mark Dean, University President LOYALTY PARTNER SCHEME LAUNCHES OPENING FANS SOCIAL EVENT GAME PREVIEW H U L L P I R A T E S V M I L T O N K E Y N E S L I G H T N I N G The predicted demise of Sheffield Steeldogs, The Pirate’s impressive start to the ‘friendly’ following an exodus of players during the season saw them extend their form from the summer, proved to be premature after their Playoffs, with two wins over Peterborough friendly fixtures with MK Lightning. Phantoms. Hull’s emphasis remains firmly on Sheffield demonstrated the magnitude of the attack and judging by its performance against task facing the former EIHL side in their the Phantoms, the Davies-Hewitt- efforts to make an impression in UK ice Chamberlain axis is already firing. Add to this, hockey’s new second tier. While the two two potent imports in Peter Fabus and Olegs defeats may not be a reliable marker, given Sislannikovs and only the strongest defences the breadth of talent among MK’s ranks, in the National League will be able to resist there is a sense that MK will take time to find their onslaught.