1.3 Impact of Invasive Aquatic Plants on Waterfowl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Updated Checklist of Aquatic Plants of Myanmar and Thailand

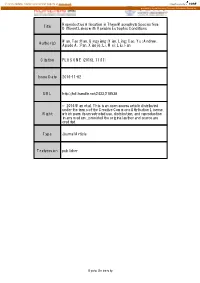

Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Taxonomic paper An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand Yu Ito†, Anders S. Barfod‡ † University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand ‡ Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark Corresponding author: Yu Ito ([email protected]) Academic editor: Quentin Groom Received: 04 Nov 2013 | Accepted: 29 Dec 2013 | Published: 06 Jan 2014 Citation: Ito Y, Barfod A (2014) An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand. Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Abstract The flora of Tropical Asia is among the richest in the world, yet the actual diversity is estimated to be much higher than previously reported. Myanmar and Thailand are adjacent countries that together occupy more than the half the area of continental Tropical Asia. This geographic area is diverse ecologically, ranging from cool-temperate to tropical climates, and includes from coast, rainforests and high mountain elevations. An updated checklist of aquatic plants, which includes 78 species in 44 genera from 24 families, are presented based on floristic works. This number includes seven species, that have never been listed in the previous floras and checklists. The species (excluding non-indigenous taxa) were categorized by five geographic groups with the exception of to reflect the rich diversity of the countries' floras. Keywords Aquatic plants, flora, Myanmar, Thailand © Ito Y, Barfod A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Introduction to Common Native & Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska

Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska Cover photographs by (top to bottom, left to right): Tara Chestnut/Hannah E. Anderson, Jamie Fenneman, Vanessa Morgan, Dana Visalli, Jamie Fenneman, Lynda K. Moore and Denny Lassuy. Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska This document is based on An Aquatic Plant Identification Manual for Washington’s Freshwater Plants, which was modified with permission from the Washington State Department of Ecology, by the Center for Lakes and Reservoirs at Portland State University for Alaska Department of Fish and Game US Fish & Wildlife Service - Coastal Program US Fish & Wildlife Service - Aquatic Invasive Species Program December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................ x Introduction Overview ............................................................................. xvi How to Use This Manual .................................................... xvi Categories of Special Interest Imperiled, Rare and Uncommon Aquatic Species ..................... xx Indigenous Peoples Use of Aquatic Plants .............................. xxi Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts ................................................................................. xxi Vectors ................................................................................. xxii Prevention Tips .................................................... xxii Early Detection and Reporting -

Nature Conservation

J. Nat. Conserv. 11, – (2003) Journal for © Urban & Fischer Verlag http://www.urbanfischer.de/journals/jnc Nature Conservation Constructing Red Numbers for setting conservation priorities of endangered plant species: Israeli flora as a test case Yuval Sapir1*, Avi Shmida1 & Ori Fragman1,2 1 Rotem – Israel Plant Information Center, Dept. of Evolution, Systematics and Ecology,The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, 91904, Israel; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Present address: Botanical Garden,The Hebrew University, Givat Ram, Jerusalem 91904, Israel Abstract A common problem in conservation policy is to define the priority of a certain species to invest conservation efforts when resources are limited. We suggest a method of constructing red numbers for plant species, in order to set priorities in con- servation policy. The red number is an additive index, summarising values of four parameters: 1. Rarity – The number of sites (1 km2) where the species is present. A rare species is defined when present in 0.5% of the area or less. 2. Declining rate and habitat vulnerability – Evaluate the decreasing rate in the number of sites and/or the destruction probability of the habitat. 3. Attractivity – the flower size and the probability of cutting or exploitation of the plant. 4. Distribution type – scoring endemic species and peripheral populations. The plant species of Israel were scored for the parameters of the red number. Three hundred and seventy (370) species, 16.15% of the Israeli flora entered into the “Red List” received red numbers above 6. “Post Mortem” analysis for the 34 extinct species of Israel revealed an average red number of 8.7, significantly higher than the average of the current red list. -

1 Phylogenetic Regionalization of Marine Plants Reveals Close Evolutionary Affinities Among Disjunct Temperate Assemblages Barna

Phylogenetic regionalization of marine plants reveals close evolutionary affinities among disjunct temperate assemblages Barnabas H. Darua,b,*, Ben G. Holtc, Jean-Philippe Lessardd,e, Kowiyou Yessoufouf and T. Jonathan Daviesg,h aDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and Harvard University Herbaria, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA bDepartment of Plant Science, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20, Hatfield 0028, Pretoria, South Africa cDepartment of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Silwood Park Campus, Ascot SL5 7PY, United Kingdom dQuebec Centre for Biodiversity Science, Department of Biology, McGill University, Montreal, QC H3A 0G4, Canada eDepartment of Biology, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, H4B 1R6, Canada; fDepartment of Environmental Sciences, University of South Africa, Florida campus, Florida 1710, South Africa gDepartment of Biology, McGill University, Montreal, QC H3A 0G4, Canada hAfrican Centre for DNA Barcoding, University of Johannesburg, PO Box 524, Auckland Park, Johannesburg 2006, South Africa *Corresponding author Email: [email protected] (B.H. Daru) Running head: Phylogenetic regionalization of seagrasses 1 Abstract While our knowledge of species distributions and diversity in the terrestrial biosphere has increased sharply over the last decades, we lack equivalent knowledge of the marine world. Here, we use the phylogenetic tree of seagrasses along with their global distributions and a metric of phylogenetic beta diversity to generate a phylogenetically-based delimitation of marine phytoregions (phyloregions). We then evaluate their evolutionary affinities and explore environmental correlates of phylogenetic turnover between them. We identified 11 phyloregions based on the clustering of phylogenetic beta diversity values. Most phyloregions can be classified as either temperate or tropical, and even geographically disjunct temperate regions can harbor closely related species assemblages. -

The Genus Ruppia L. (Ruppiaceae) in the Mediterranean Region: an Overview

Aquatic Botany 124 (2015) 1–9 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Aquatic Botany journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aquabot The genus Ruppia L. (Ruppiaceae) in the Mediterranean region: An overview Anna M. Mannino a,∗, M. Menéndez b, B. Obrador b, A. Sfriso c, L. Triest d a Department of Sciences and Biological Chemical and Pharmaceutical Technologies, Section of Botany and Plant Ecology, University of Palermo, Via Archirafi 38, 90123 Palermo, Italy b Department of Ecology, University of Barcelona, Av. Diagonal 643, 08028 Barcelona, Spain c Department of Environmental Sciences, Informatics & Statistics, University Ca’ Foscari of Venice, Calle Larga S. Marta, 2137 Venice, Italy d Research Group ‘Plant Biology and Nature Management’, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Pleinlaan 2, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium article info abstract Article history: This paper reviews the current knowledge on the diversity, distribution and ecology of the genus Rup- Received 23 December 2013 pia L. in the Mediterranean region. The genus Ruppia, a cosmopolitan aquatic plant complex, is generally Received in revised form 17 February 2015 restricted to shallow waters such as coastal lagoons and brackish habitats characterized by fine sediments Accepted 19 February 2015 and high salinity fluctuations. In these habitats Ruppia meadows play an important structural and func- Available online 26 February 2015 tional role. Molecular analyses revealed the presence of 16 haplotypes in the Mediterranean region, one corresponding to Ruppia maritima L., and the others to various morphological forms of Ruppia cirrhosa Keywords: (Petagna) Grande, all together referred to as the “R. cirrhosa s.l. complex”, which also includes Ruppia Aquatic angiosperms Ruppia drepanensis Tineo. -

Seagrasses of Florida: a Review

Page 1 of 1 Seagrasses of Florida: A Review Virginia Rigdon The University of Florida Soil and Water Science Departments Introduction Seagrass communities are noted to be some of the most productive ecosystems on earth, as they provide countless ecological functions, including carbon uptake, habitat for endangered species, food sources for many commercially and recreationally important fish and shellfish, aiding nutrient cyling, and their ability to anchor the sediment bottom. These communites are in jeopardy and a wordwide decline can be attributed mainly to deterioration in water quality, due to anthropogenic activities. Seagrasses are a diverse group of submerged angiosperms, which grow in estuaries and shallow ocean shelves and form dense vegetative communities. These vascular plants are not true grasses; however, their “grass-like” qualities and their ability to adapt to a saline environment give them their name. While seagrasses can be found across the globe, they have relatively low taxonomic diversity. There are approximately 60 species of seagrasses, compared to roughly 250,000 terrestrial angiosperms (Orth, 2006). These plants can be traced back to three distinct seagrass families (Hydrocharitaceae, Cymodoceaceace complex, and Zosteraceae), which all evolved 70 million to 100 million years ago from a individual line of monocotyledonous flowering plants (Orth, 2006). The importance of these ecosystems, both ecologically and economically is well understood. The focus of this paper will be to discuss the species of seagrass in Florida, the components which affect their health and growth, and the major factors which threaten these precious and unique ecosystems, as well as programs which are in place to protect and preserve this essential resource. -

New Distributional Record of Stuckenia Pectinata (L.) Borner in Union Territory of Chandigarh, India

Journal on New Biological Reports ISSN 2319 – 1104 (Online) JNBR 7(1) 10 – 14 (2018) Published by www.researchtrend.net New Distributional Record of Stuckenia pectinata (L.) Borner in Union Territory of Chandigarh, India Malkiat Chand Sidhu, Shweta Puri and Amrik Singh Ahluwalia Department of Botany, Panjab University, Chandigarh, 160014 *Corresponding author: [email protected] | Received: 27 December 2017 | Accepted: 14 February 2018 | ABSTRACT Stuckenia pectinata has been reported for the first time from Sukhna Wetland, Chandigarh, India. It belongs to family Potamogetonaceae and has few morphological variants. It is a filiform, submerged, perennial and aquatic plant. Different plant parts are important as a source of food for many water fowls. It is believed that this species possibly has reached at the present study site through migratory birds. Key words: Aquatic species, Stuckenia pectinata, Potamogetonaceae, Sukhna, Wetland. INTRODUCTION polluted conditions. It may likely be the reason for its wider adaptability in different water bodies. Stuckenia pectinata (L.) Borner (syn. Potamogeton Both seeds and tubers help the plants to pectinatus) is species of genus Stuckenia. It is survive in winters (Yeo 1965; Hangelbroek et al. commonly called as „Sago pondweed‟ or „Fennel 2003). These are also the main source of dispersal weed‟ and distributed throughout the world. It is and important food for waterfowls due to their submerged macrophyte, occurring in a variety of nutritional value. Leaves, stems and roots are also habitats including eutrophic, stagnant to running consumed by ducks and water fowls. This plant not water and in different types of ditches, lakes, ponds only protects fishes, grass carp and invertebrates and rivers (Hulten & Fries 1986; Wiegleb & from predators but also provides a place for them to Kaplan 1998). -

The Rise of Ruppia in Seagrass Beds: Changes in Coastal Environment and Research Needs

In: Handbook on Environmental Quality ISBN: 978-1-60741-420-9 Editors: E. K. Drury, T. S. Pridgen, pp. - © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 12 THE RISE OF RUPPIA IN SEAGRASS BEDS: CHANGES IN COASTAL ENVIRONMENT AND RESEARCH NEEDS Hyun Jung Cho*1, Patrick Biber*2 and Cristina Nica1 1 Department of Biology; Jackson State University; 1400 Lynch St., Jackson, MS 39217, USA 2 Department of Coastal Sciences; The University of Southern Mississippi; 703 East Beach Drive, Ocean Springs, MS 39564 ABSTRACT It is well known that the global seagrass beds have been declining due to combining effects of natural/anthropogenic disturbances. Restoration efforts have focused on revegetation of the lost seagrass species, which may well work in cases the seagrass loss is recent and the habitat quality has not been altered substantially. Recent studies in several estuaries in the U.S. report the similar change in the seagrass community structures: much of the habitats previously dominated by stable seagrasses (Thalassia testudinum and Syringodium filiforme in tropical and Zostera marina in temperate regions) are now replaced by Ruppia maritima, an opportunistic, pioneer species that is highly dependent on sexual reproduction. The relative increases of R. maritima in seagrass habitats indicate that: (1) the coastal environmental quality has been altered to be more conducive to this species; (2) the quality of environmental services that seagrass beds play also have been changed; and (3) strategies for seagrass restoration and habitat management need to be adjusted. Unlike Zostera or Thalassia, Ruppia maritima beds are known for their seasonal and annual fluctuations. The authors’ previous and on-going research and restoration efforts as well as literature reviews are presented to discuss the causes for and the potential impacts of this change in seagrass community on the coastal ecosystem and future restoration strategies. -

REPORT on the INVASIVE SPECIES COMPONENT of the MEDA’S, TDA & SAP for the ASCLME PROJECT

REPORT ON THE INVASIVE SPECIES COMPONENT OF THE MEDA’s, TDA & SAP FOR THE ASCLME PROJECT Adnan Awad Consultant Cape Town, South Africa 1 Table of Contents PART I: INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT ..................................................................................... 3 1. PROJECT BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Scope of Project ............................................................................................................ 4 1.3 Project Objectives ......................................................................................................... 4 2. REVISIONS & ADDITIONS TO THE PROJECT .................................................................................... 5 3. METHODS ............................................................................................................................ 5 3.1 Desktop Review ............................................................................................................ 5 3.2 Recommendations & Guidelines .................................................................................... 6 3.3 Training......................................................................................................................... 6 PART II: DESK TOP STUDY OF RELEVANT ACTIVITIES & INFORMATION FOR MEDA/TDA/SAP ......... 7 4. BASELINE -

Title Reproductive Allocation in Three Macrophyte Species from Different

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Reproductive Allocation in Three Macrophyte Species from Title Different Lakes with Variable Eutrophic Conditions Wan, Tao; Han, Qingxiang; Xian, Ling; Cao, Yu; Andrew, Author(s) Apudo A.; Pan, Xiaojie; Li, Wei; Liu, Fan Citation PLOS ONE (2016), 11(11) Issue Date 2016-11-02 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/218538 © 2016 Wan et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, Right which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University RESEARCH ARTICLE Reproductive Allocation in Three Macrophyte Species from Different Lakes with Variable Eutrophic Conditions Tao Wan1,2³, Qingxiang Han4³, Ling Xian3, Yu Cao3, Apudo A. Andrew2,3, Xiaojie Pan5, Wei Li3, Fan Liu2,3* 1 Key Laboratory of Southern Subtropical Plant Diversity, Fairy Lake Botanical Garden, Shenzhen & Chinese Academy of Science, Shenzhen 518004, P. R. China, 2 Sino-Africa Joint Research Center, CAS, Wuhan 430074, P. R. China, 3 Key Laboratory of Aquatic Botany and Watershed Ecology, The Chinese a11111 Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430074, P. R. China, 4 Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan, 5 Key Laboratory of Ecological Impacts of Hydraulic -Projects and Restoration of Aquatic Ecosystem of Ministry of Water Resources. Institute of Hydroecology, MWR&CAS, Wuhan 430074, China ³ These authors are co-first authors on this work. * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Citation: Wan T, Han Q, Xian L, Cao Y, Andrew AA, Abstract Pan X, et al. -

Monitoring Groningen Sea Ports Non-Indigenous Species and Risks from Ballast Water in Eemshaven and Delfzijl

Monitoring Groningen Sea Ports Non-indigenous species and risks from ballast water in Eemshaven and Delfzijl Authors: D.M.E. Slijkerman, S.T. Glorius, A. Gittenberger¹, B.E. van der Weide, O.G. Bos, Wageningen University & M. Rensing¹, G.A. de Groot² Research Report C045/17 A ¹ GiMaRiS ² Wageningen Environmental Research Monitoring Groningen Sea Ports Non-indigenous species and risks from ballast water in Eemshaven and Delfzijl Authors: D.M.E. Slijkerman, S.T. Glorius, A. Gittenberger1, B.E. van der Weide, O.G. Bos, M. Rensing1, G.A. de Groot2 1GiMaRiS 2Wageningen Environmental Research Publication date: June 2017 Wageningen Marine Research Den Helder, June 2017 Wageningen Marine Research report C045/17 A Monitoring Groningen Sea Ports, Non-indigenous species and risks from ballast water in Eemshaven and Delfzijl; D.M.E. Slijkerman, S.T. Glorius, A. Gittenberger, B.E. van der Weide, O.G. Bos, M. Rensing, G.A. de Groot, 2017. Wageningen, Wageningen Marine Research (University & Research centre), Wageningen Marine Research report C045/17 A. 81 pp. Keywords: Harbour monitoring, Non- Indigenous Species, eDNA, metabarcoding, Ballast water This report is free to download from https://doi.org/10.18174/417717 Wageningen Marine Research provides no printed copies of reports. This project was funded by “Demonstratie Ballast Waterbehandelings Barge kenmerk WF220396”, under the Subsidy statute by Waddenfonds 2012, and KB project HI Marine Portfolio (KB-24-003- 012). Client: DAMEN Green Solutions Attn.: Dhr. R. van Dinteren Industrieterrein Avelingen West 20 4202 MS Gorinchem Acknowledgements and partners Wageningen Marine Research is ISO 9001:2008 certified. © 2016 Wageningen Marine Research Wageningen UR Wageningen Marine Research The Management of Wageningen Marine Research is not responsible for resulting institute of Stichting Wageningen damage, as well as for damage resulting from the application of results or Research is registered in the Dutch research obtained by Wageningen Marine Research, its clients or any claims traderecord nr. -

Bay Grass Identification Key

Bay Grass Identification Key Select the Bookmark tab to the left or scroll down to see the individual SAV. There is a Dichotomous Key at the end of this document. Maryland DepartmentofNatural Resources Bladderwort Utricularia spp. Native to the Chesapeake Bay Family - Lentibulariaceae Distribution - Several species of bladderwort occur in the Chesapeake Bay region, prima- rily in the quiet freshwater of ponds and ditches. Bladderworts can also be found on moist soils associated with wetlands. Recognition - Bladderworts are small herbs that are found floating in shallow water or growing on very moist soils. The stems are generally horizontal and submerged. Leaves are alter- nate, linear or dissected often appearing opposite or whorled. The branches are often much dissected, appear rootlike and have bladders with bristles around the openings. Bladderworts are considered carnivorous because minute animals can be trapped and digested in the bladders that occur on the underwater leaves. Bladderwort Maryland DepartmentofNatural Resources Common Waterweed Elodea canadensis Native to Chesapeake Bay Family - Hydrocharitaceae Distribution - Common waterweed is primarily a freshwater species, and occasionally grows in brackish upper reaches in many of the Bay’s tributaries. It prefers loamy soil, slow-moving water with high nitrogen and phosphorous concentrations. Recognition - The leaves of common waterweed can vary greatly in width, size and bunching. In general, the leaves are linear to oval with minutely toothed margins and blunt tips. Leaves have no leaf stalks, and occur in whorls of 3 at stem nodes, becoming more crowded toward the stem tips. Common waterweed has slender, branching stems and a weak, thread-like root system.