18-19.Pdf (326.5Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Kelleway Passed Away on 16 November 1944 in Lindfield, Sydney

Charle s Kelleway (188 6 - 1944) Australia n Cricketer (1910/11 - 1928/29) NS W Cricketer (1907/0 8 - 1928/29) • Born in Lismore on 25 April 1886. • Right-hand bat and right-arm fast-medium bowler. • North Coastal Cricket Zone’s first Australian capped player. He played 26 test matches, and 132 first class matches. • He was the original captain of the AIF team that played matches in England after the end of World War I. • In 26 tests he scored 1422 runs at 37.42 with three centuries and six half-centuries, and he took 52 wickets at 32.36 with a best of 5-33. • He was the first of just four Australians to score a century (114) and take five wickets in an innings (5/33) in the same test. He did this against South Africa in the Triangular Test series in England in 1912. Only Jack Gregory, Keith Miller and Richie Benaud have duplicated his feat for Australia. • He is the only player to play test cricket with both Victor Trumper and Don Bradman. • In 132 first-class matches he scored 6389 runs at 35.10 with 15 centuries and 28 half-centuries. With the ball, he took 339 wickets at 26.33 with 10 five wicket performances. Amazingly, he bowled almost half (164) of these. He bowled more than half (111) of his victims for New South Wales. • In 57 first-class matches for New South Wales he scored 3031 runs at 37.88 with 10 centuries and 11 half-centuries. He took 215 wickets at 23.90 with seven five-wicket performances, three of these being seven wicket hauls, with a best of 7-39. -

The Natwest Series 2001

The NatWest Series 2001 CONTENTS Saturday23June 2 Match review – Australia v England 6 Regulations, umpires & 2002 fixtures 3&4 Final preview – Australia v Pakistan 7 2000 NatWest Series results & One day Final act of a 5 2001 fixtures, results & averages records thrilling series AUSTRALIA and Pakistan are both in superb form as they prepare to bring the curtain down on an eventful tournament having both won their last group games. Pakistan claimed the honours in the dress rehearsal for the final with a memo- rable victory over the world champions in a dramatic day/night encounter at Trent Bridge on Tuesday. The game lived up to its billing right from the onset as Saeed Anwar and Saleem Elahi tore into the Australia attack. Elahi was in particularly impressive form, blast- ing 79 from 91 balls as Pakistan plundered 290 from their 50 overs. But, never wanting to be outdone, the Australians responded in fine style with Adam Gilchrist attacking the Pakistan bowling with equal relish. The wicketkeep- er sensationally raced to his 20th one-day international half-century in just 29 balls on his way to a quick-fire 70. Once Saqlain Mushtaq had ended his 44-ball knock however, skipper Waqar Younis stepped up to take the game by the scruff of the neck. The pace star is bowling as well as he has done in years as his side come to the end of their tour of England and his figures of six for 59 fully deserved the man of the match award and to take his side to victory. -

Bankstown District Cricket Club

Honorary Secretary 67 Thomas Street Picnic Point 2213 Mobile – 0417 257984 [email protected] Productivity Commission Inquiry into the Australia’s Gambling Industry GPO Box 1428 Canberra ACT 2601 Background The Bankstown District Cricket Club was formed in 1950 and plays a leadership role coordinating the development of cricket and general sports and recreation activities in the City of Bankstown and nearby communities. Our stakeholders include: • Bankstown District Cricket Association • Bankstown Women’s Cricket Club • Bankstown Schools Cricket Association • Bankstown Cricket Coaches and Managers Association • Bankstown District Cricket Umpires Association • Recreation Sports and Aquatics Club (sport for children with disabilities ) • NSW Blind Cricket Association • NSW Deaf Cricket Association • All Stars Winter Cricket Association (under 10’s – 14’s) Our vision is to become: • a benchmark for amateur sporting clubs in Australia • a leader and valued contributor in the Bankstown Community This vision is supported by six strategic themes that drive our activities: • Facilities Development • Brand and Culture • On-field Performance • Organisation and Governance • Stakeholder Relationships • Financial Sustainability Key Achievements • Produced five Australian Men’s Test players • Produced three Australian Women’s Test Players • Produced 20 NSW representatives • Produced 16 NSW Male Age Team representatives between 1990 – 2008 • Produced 7 NSW Women’s Age Team representatives between 2002 - 2008 • Raised $1.5m to develop a first class regional cricket facility in Bankstown (Memorial Oval) • Raised $25k in support of charities in Sri Lanka in 2008 • Donated +$50k in recycled cricket equipment to Ugandan Cricket Association following appeals in 2006 and 2007 • Hosted International, National and regional cricket events including Blind Cricket Ashes Series, National Deaf Cricket Championships and the ICC Women’s World Cup. -

Extract Catalogue for Auction

Page:1 May 19, 2019 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1949 Onwards Ex Lot 94 94 1955-66 Melbourne Cricket Club membership badges complete run 1955-56 to 1965-66, all the scarce Country memberships. Very fine condition. (11) 120 95 1960 'The Tied Test', Australia v West Indies, 1st Test at Brisbane, display comprising action picture signed by Wes Hall & Richie Benaud, limited edition 372/1000, window mounted, framed & glazed, overall 88x63cm. With CoA. 100 Lot 96 96 1972-73 Jack Ryder Medal dinner menu for the inaugural medal presentation with 18 signatures including Jack Ryder, Don Bradman, Bill Ponsford, Lindsay Hassett and inaugural winner Ron Bird. Very scarce. 200 Lot 97 97 1977 Centenary Test collection including Autograph Book with 254 signatures of current & former Test players including Harold Larwood, Percy Fender, Peter May, Clarrie Grimmett, Ray Lindwall, Richie Benaud, Bill Brown; entree cards (4), dinner menu, programme & book. 250 98 - Print 'Melbourne Cricket Club 1877' with c37 signatures including Harold Larwood, Denis Compton, Len Hutton, Ted Dexter & Ross Edwards; window mounted, framed & glazed, overall 75x58cm. 100 99 - Strip of 5 reserved seat tickets, one for each day of the Centenary Test, Australia v England at MCG on 12th-17th March, framed, overall 27x55cm. Plus another framed display with 9 reserved seat tickets. (2) 150 100 - 'Great Moments' poster, with signatures of captains Greg Chappell & Tony Greig, limited edition 49/550, framed & glazed, overall 112x86cm. 150 Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au May 19, 2019 CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1949 Onwards (continued) Lot Type Grading Description Est $A Ex Lot 101 101 1977-86 Photographs noted Australian team photos (6) from 1977-1986; framed photos of Ray Bright (6) including press photo of Bright's 100th match for Victoria (becoming Victoria's most capped player, overtaking Bill Lawry's 99); artworks of cricketer & two-up player. -

Cricket Club

If you wander around any uni campus and ask about the Whatever your dreams, TOWER can help you future, you'll hear things like turn them into reality: "I have no idea what it'll be like - everything seems up for grabs Superannuation: This is an essential part of a strong self-reliant future. The sooner you start the greater the rewards will be as you will reap the Ask about nfioney and you'll hear benefits of compounding earnings. Income Protection: "What money?", or - "Sure I'd like more money! Who is TOWER? TOWER can help you ensure that your financial dreams don't turn into a nightmare when something goes wrong. Income protection is a safety net in case, for some reason, you can't work. We can help make sure you still receive an income. It's especially relevant for There has never been a time when there have been so those embarking on careers in the legal, medical and accountancy professions. many opportunities and options to carve out your The history of the TOWER Financial Services Croup began over 1 30 future. Tomorrow belongs to those who dare to years ago. TOWER started out as the New Zealand Government Life Office, grew to be New Zealand's largest life insurance office, privatised in the late As everyone's situation is different and will vary over time, prior to making any investment or financial planning decision, you should dream, give it a go, and take control of their seek the advice of a qualified financial adviser. own destiny. -

Justice Qayyum's Report

PART I BACKGROUND TO INQUIRY 1. Cricket has always put itself forth as a gentleman’s game. However, this aspect of the game has come under strain time and again, sadly with increasing regularity. From BodyLine to Trevor Chappel bowling under-arm, from sledging to ball tampering, instances of gamesmanship have been on the rise. Instances of sportsmanship like Courtney Walsh refusing to run out a Pakistani batsman for backing up too soon in a crucial match of the 1987 World Cup; Imran Khan, as Captain calling back his counterpart Kris Srikanth to bat again after the latter was annoyed with the decision of the umpire; batsmen like Majid Khan walking if they knew they were out; are becoming rarer yet. Now, with the massive influx of money and sheer increase in number of matches played, cricket has become big business. Now like other sports before it (Baseball (the Chicago ‘Black-Sox’ against the Cincinnati Reds in the 1919 World Series), Football (allegations against Bruce Grobelar; lights going out at the Valley, home of Charlton Football club)) Cricket Inquiry Report Page 1 Cricket faces the threat of match-fixing, the most serious threat the game has faced in its life. 2. Match-fixing is an international threat. It is quite possibly an international reality too. Donald Topley, a former county cricketer, wrote in the Sunday Mirror in 1994 that in a county match between Essex and Lancashire in 1991 Season, both the teams were heavily paid to fix the match. Time and again, former and present cricketers (e.g. Manoj Prabhakar going into pre-mature retirement and alleging match-fixing against the Indian team; the Indian Team refusing to play against Pakistan at Sharjah after their loss in the Wills Trophy 1991 claiming matches there were fixed) accused different teams of match-fixing. -

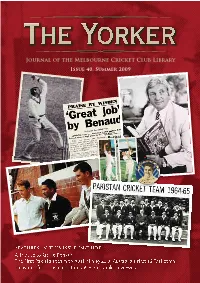

Issue 40: Summer 2009/10

Journal of the Melbourne Cricket Club Library Issue 40, Summer 2009 This Issue From our Summer 2009/10 edition Ken Williams looks at the fi rst Pakistan tour of Australia, 45 years ago. We also pay tribute to Richie Benaud's role in cricket, as he undertakes his last Test series of ball-by-ball commentary and wish him luck in his future endeavours in the cricket media. Ross Perry presents an analysis of Australia's fi rst 16-Test winning streak from October 1999 to March 2001. A future issue of The Yorker will cover their second run of 16 Test victories. We note that part two of Trevor Ruddell's article detailing the development of the rules of Australian football has been delayed until our next issue, which is due around Easter 2010. THE EDITORS Treasures from the Collections The day Don Bradman met his match in Frank Thorn On Saturday, February 25, 1939 a large crowd gathered in the Melbourne District competition throughout the at the Adelaide Oval for the second day’s play in the fi nal 1930s, during which time he captured 266 wickets at 20.20. Sheffi eld Shield match of the season, between South Despite his impressive club record, he played only seven Australia and Victoria. The fans came more in anticipation games for Victoria, in which he captured 24 wickets at an of witnessing the setting of a world record than in support average of 26.83. Remarkably, the two matches in which of the home side, which began the game one point ahead he dismissed Bradman were his only Shield appearances, of its opponent on the Shield table. -

Mark Waugh Cricket

Mark Waugh Cricket Mark Waugh was cricket made classy. The twin brother of Aussie captain Steve, ‘Junior’ was one of the world's most elegant and gifted stroke-makers. His game was characterised by an ability to drive, cut, pull and loft the ball so effortlessly that it could make him look disdainful of the talents of bowlers. Mark Taylor called Waugh “the best-looking leg-side player I've seen in my time. Anything drifting into his pads is hit beautifully.” Junior made his name as a middle- order player for New South Wales, twice winning the Sheffield Shield Cricketer of the Year title. He was finally picked for his Test debut in 1991 against England in the Fourth Test at the Adelaide Oval, ironically at the expense of his out-of-form brother. Waugh came to the crease on the first day with Australia in trouble at 4/104 and the situation deteriorated to 5/126 when Greg Matthews joined him at the crease. Junior brought up his century with a square drive close to stumps. Phil Wilkins of the SMH wrote that "Such a maiden Test century could hardly have been surpassed for commanding presence." To complement his batting skills, Junior was a handy part- time bowler and a wonderful fieldsman - he had few rivals to match his freakish brilliance in the field. Mark Waugh is a familiar TV face these days. His easy- going manner and sense of humour make him a classy choice as a guest speaker. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DuwKVnLDfPk www.thekfaktor.com . -

Is Australian Cricket Racist?

Is Australian cricket racist? What they said… ‘There wasn’t a match I wasn’t racially abused in when I went out to bat’ John McGuire, an Indigenous player who is second in the all-time run-scoring list for the first-grade competition in Western Australia ‘We have to be vigilant against any comments, against any actions, even though it’s conducted by only a very small minority of people’ New South Wales premier Gladys Berejiklian warning cricket fans against making racially abusive comments The issue at a glance On January 9. 2021, on day three of the India vs Australia test match being played on the Sydney Cricket Ground, India captain Ajinkya Rahane and other senior players spoke to the umpires at the end of play. It was subsequently revealed that they were alleging racist abuse from some sections of the crowd. On January 10, play was stopped for eight minutes following claims of more alleged abuse. At least six fans were removed from their seats for allegedly making racist comments after Mohammed Siraj ran in from the fine-leg boundary, alerting teammates before umpires passed on the message to security and police. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2021/jan/10/india-report-alleged-racist-abuse-from-scg- crowd-during-third-test A subsequent enquiry confirmed that racial abuse had occurred; however, the six spectators who had been escorted from the stadium were not the perpetrators. https://www.skysports.com/cricket/news/12123/12200065/cricket-australia-confirms-india- players-were-racially-abused-in-sydney-six-fans-cleared The incident has provoked significant discussion regarding the extent of racism in Australian cricket. -

Comparative Analysis of Top Test Batsmen Before and After 20 Century

Joshi & Raizada (2020): Comparative analysis of top test batsmen Nov 2020 Vol. 23 Issue 17 Comparative analysis of top Test batsmen before and after 20th century Pushkar Joshi1 and Shiny Raizada2* 1Student, MBA, 2Assistant Professor,Symbiosis School of Sports Sciences, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India *Corresponding author: [email protected] (Raizada) Abstract Background:This research paper derives that which generation of top batsmen (before 20th century and after 20th century) are best when compared on certain parameters.Methods: The authorcompared both generation top batsmen on parameters such as overall average, average away from home, number of not outs and outs during that particular batsman’s career (weighted batting average). Conclusion: This research concludes that the top batsmen after 20th century have an edge over top batsmen before 20th century. Keywords: Bowling Average, Cricket, Overall Batting Average, Weighted Batting Average, Wickets How to cite this article: Joshi P, Raizada S (2020): Comparative analysis of top test batsmen before and after 20th century, Ann Trop Med & Public Health; 23(S17): SP231738. DOI: http://doi.org/10.36295/ASRO.2020.231738 1. Introduction: Cricket as a game has evolved as an intense competition after its invention in early 17th century. Truth be told, a progression of Codes of Law has administered this game for more than 250 years. Much the same as baseball (which could be called cricket's cousin in light of their likenesses), cricket's fundamental element is the technique in question and that is the primary motivation behind why cricket fans love the game to such an extent. -

Matador Bbqs One Day Cup Winners “Some Plan B’S Are Smarter Than Others, Don’T Drink and Drive.” NIGHTWATCHMAN NATHAN LYON

Matador BBQs One Day Cup Winners “Some plan b’s are smarter than others, don’t drink and drive.” NIGHTWATCHMAN NATHAN LYON Supporting the nightwatchmen of NSW We thank Cricket NSW for sharing our vision, to help develop and improve road safety across NSW. Our partnership with Cricket NSW continues to extend the Plan B drink driving message and engages the community to make positive transport choices to get home safely after a night out. With the introduction of the Plan B regional Bash, we are now reaching more Cricket fans and delivering the Plan B message in country areas. Transport for NSW look forward to continuing our strong partnership and wish the team the best of luck for the season ahead. Contents 2 Members of the Association 61 Toyota Futures League / NSW Second XI 3 Staff 62 U/19 Male National 4 From the Chairman Championships 6 From the Chief Executive 63 U/18 Female National 8 Strategy for NSW/ACT Championships Cricket 2015/16 64 U/17 Male National 10 Tributes Championships 11 Retirements 65 U/15 Female National Championships 13 The Steve Waugh/Belinda Clark Medal Dinner 66 Commonwealth Bank Australian Country Cricket Championships 14 Australian Representatives – Men’s 67 National Indigenous Championships 16 Australian Representatives – Women’s 68 McDonald’s Sydney Premier Grade – Men’s Competition 17 International Matches Played Lauren Cheatle in NSW 73 McDonald’s Sydney Premier Grade – Women’s Competition 18 NSW Blues Coach’s Report 75 McDonald’s Sydney Shires 19 Sheffield Shield 77 Cricket Performance 24 Sheffield Shield -

Xref Cricket Catalogue for Auction

Page:1 Oct 20, 2019 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A SPORTING MEMORABILIA - General & Miscellaneous Lots 2 Eclectic group comprising 'The First Over' silk cricket picture; Wayne Carey mini football locker; 1973 Caulfield Cup glass; 'Dawn Fraser' swimming goggles; and 'Greg Norman' golf glove. (5 items) 100 3 Autographs on video cases noted Lionel Rose, Jeff Fenech, Dennis Lillee, Kevin Sheedy, Robert Harvey, Peter Hudson, Dennis Pagan & Wayne Carey. (7) 100 4 Books & Magazines 1947-56 'Sporting Life' magazines (31); cricket books (54) including 'Bradman - The Illustrated Biography' by Page [1983] & 'Coach - Darren Lehmann' [2016]; golf including 'The Sandbelt - Melbourne's Golfing Haven' limited edition 52/100 by Daley & Scaletti [2001] & 'Golfing Architecture - A Worldwide Perspective Volume 3' by Daley [2005]. Ex Ken Piesse Library. (118) 200 6 Ceramic Plates Royal Doulton 'The History of the Ashes'; Coalport 'Centenary of the Ashes'; AOF 'XXIIIrd Olympiad Los Angeles 1984'; Bendigo Pottery '500th Grand Prix Adelaide 1990'; plus Gary Ablett Sr caricature mug & cold cast bronze horse's head. (6) 150 CRICKET - General & Miscellaneous Lots 29 Collection including range of 1977 Centenary Test souvenirs; replica Ashes urn (repaired); stamps, covers, FDCs & coins; cricket mugs (3); book 'The Art of Bradman'; 1987 cricket medal from Masters Games; also pair of cups inscribed 'HM King Edward VIII, Crowned May 12th 1937' in anticipation of his cancelled Coronation. Inspection will reward. (Qty) 100 30 Balance of collection including Don Bradman signed postcard & signed FDC; cricket books (23) including '200 Seasons of Australian Cricket'; cricket magazines (c.120); plus 1960s 'Football Record's (2). (Qty) 120 Ex Lot 31 31 Autographs International Test Cricketers signed cards all-different collection mounted and identified on 8 sheets with players from England, Australia, South Africa, West Indies, India, New Zealand, Pakistan & Sri Lanka; including Alec Bedser, Rod Marsh, Alan Donald, Lance Gibbs, Kapil Dev, Martin Crowe, Intikhab Alam & Muttiah Muralitharan.