Diagnostic Accuracy of Scintigraphy and Sonography for Biliary Atresia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Small Bowel Obstruction After Laparoscopic Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass Presenting As Acute Pancreatitis: a Case Report

Netherlands Journal of Critical Care Submitted January 2018; Accepted April 2018 CASE REPORT Small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass presenting as acute pancreatitis: a case report N. Henning1, R.K. Linskens2, E.E.M. Schepers-van der Sterren3, B. Speelberg1 Department of 1Intensive Care, 2Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and 3Surgery, Sint Anna Hospital, Geldrop, the Netherlands. Correspondence N. Henning - [email protected] Keywords - Roux-en-Y, gastric bypass, pancreatitis, pancreatic enzymes, small bowel obstruction, biliopancreatic limb obstruction. Abstract Small bowel obstruction is a common and potentially life-threatening bowel obstruction within this complication after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. population, because misdiagnosis We describe a 30-year-old woman who previously underwent can have disastrous outcomes.[1,3-5,7] gastric bypass surgery. She was admitted to the emergency In this report we describe the department with epigastric pain and elevated serum lipase levels. difficulty of diagnosing small Conservative treatment was started for acute pancreatitis, but she bowel obstruction in post- showed rapid clinical deterioration due to uncontrollable pain and LRYGB patients and why frequent excessive vomiting. An abdominal computed tomography elevated pancreatic enzymes scan revealed small bowel obstruction and surgeons performed can indicate an obstruction in an exploratory laparotomy with adhesiolysis. Our patient quickly these patients. The purpose of improved after surgery and could be discharged home. This case this manuscript is to emphasise report emphasises that in post-bypass patients with elevated Figure 1. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass that in post-bypass patients with pancreatic enzymes, small bowel obstruction should be considered ©Ethicon, Inc. -

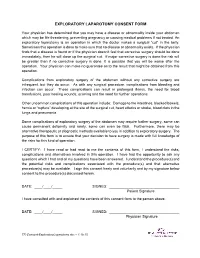

Exploratory Laparotomy.Docx

EXPLORATORY LAPAROTOMY CONSENT FORM Your physician has determined that you may have a disease or abnormality inside your abdomen which may be life threatening, preventing pregnancy or causing medical problems if not treated. An exploratory laparotomy is an operation in which the doctor makes a surgical “cut” in the belly. Sometimes this operation is done to make sure that no disease or abnormality exists. If the physician finds that a disease is found or if the physician doesn’t feel that corrective surgery should be done immediately, then he will close up the surgical cut. If major corrective surgery is done the risk will be greater than if no corrective surgery is done. It is possible that you will be worse after the operation. Your physician can make no guarantee as to the result that might be obtained from this operation. Complications from exploratory surgery of the abdomen without any corrective surgery are infrequent, but they do occur. As with any surgical procedure, complications from bleeding and infection can occur. These complications can result in prolonged illness, the need for blood transfusions, poor healing wounds, scarring and the need for further operations. Other uncommon complications of this operation include: Damage to the intestines, blocked bowels, hernia or “rupture” developing at the site of the surgical cut, heart attacks or stroke, blood clots in the lungs and pneumonia. Some complications of exploratory surgery of the abdomen may require further surgery, some can cause permanent deformity and rarely, some can even be fatal. Furthermore, there may be alternative therapeutic or diagnostic methods available to you in addition to exploratory surgery. -

Abdominal Exploratory and Closure

Abdominal exploratory and closure 10.1 Diagnostic procedures 10.1.1 Paracentesis 10.1.1.1 Paracentesis technique 10.1.2 Enterocentesis 10.1.2.1 Enterocentesis technique 10.2 Opening of the abdominal cavity 10.2.1 Introduction 10.2.2 Position of the animal 10.2.3 Location of incision 10.2.4 Type of incision 10.2.4.1 Through-and-through incision 10.2.4.2 Complete grid Incision 10.2.4.3 Partial grid incision 10.2.5 Laparotomy in the bovine 10.2.5.1 Indications 10.2.5.2 Through-and-through incision 10.2.5.3 Partial grid incision 10.2.5.4 Complete grid incision 10.2.6 Laparotomy in small ruminants Chapter 10 10.2.7 Laparotomy in the horse 10.2.7.1 Indications 10.2.7.2 The median coeliotomy 10.2.7.3 The paramedian laparotomy 10.2.8 Coeliotomy in the dog and the cat 10.2.8.1 Indications 10.2.8.2 The median coeliotomy 10.2.8.3 The flank or paracostal incision 10.3 Minimally invasive techniques 10.4 Abdominal procedures 10.4.1 The rumen (bovine, small ruminants) 10.4.1.1 Introduction 10.4.1.2 Rumenotomy 10.4.2 The abomasum (bovine) 10.4.3 The stomach (horse, dog and cat) 10.4.3.1 Introduction 10.4.3.2 Gastrotomy in the dog and the cat 10.4.4 The small- and large intestines 10.4.4.1 Introduction 10.4.4.1.1 Simple mechanical ileus 10.4.4.1.2 Strangulating ileus 10.4.4.1.3 Paralytic ileus 10.4.4.2 Diagnostics 10.4.4.3 Therapy 10.4.4.3.1 Enterotomy 10.4.4.3.2 Enterectomy 10.4.5 The bladder 10.4.5.1 Introduction 10.4.5.2 Urolithiasis in bovine and equine 10.4.5.3 Cystotomy in the horse 10.4.5.3.1 Laparocystotomy 10.4.5.3.2 Pararectal cystotomy 10.4.5.4 Urolithiasis in the dog and the cat 10.4.5.5 Cystotomy in the dog and the cat 10.4.6 The uterus 10.4.6.1 Opening and closing of the uterus 10.4.6.2 Ovariectomy and ovariohysterectomy in dog and cat Chapter 10 176 Chapter 10 Abdominal exploratory and closure 10.1 Diagnostic procedures 10.1.1 Paracentesis paracentesis Paracentesis is the puncturing of the abdominal cavity. -

Exploratory Laparotomy Following Penetrating Abdominal Injuries: a Cohort Study from a Referral Hospital in Erbil, Kurdistan Region in Iraq

Exploratory laparotomy following penetrating abdominal injuries: a cohort study from a referral hospital in Erbil, Kurdistan region in Iraq Research protocol 1 November 2017 FINAL version Table of Contents Protocol Details .............................................................................................................. 3 Signatures of all Investigators Involved in the Study .................................................... 4 Summary ........................................................................................................................ 5 List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... 6 List of Definitions .......................................................................................................... 7 Background .................................................................................................................... 8 Justification .................................................................................................................... 9 Aim of Study .................................................................................................................. 9 Investigation Plan ......................................................................................................... 10 Study Population .......................................................................................................... 10 Data ............................................................................................................................. -

Digestive Endoscopy in Five Decades

■ COLLEGE LECTURES Digestive endoscopy in five decades Peter B Cotton ABSTRACT – The world of gastroenterology scopy. So-called semi-flexible gastroscopes were changed forever when flexible endoscopes cumbersome and used infrequently by only a few became available in the 1960s. Diagnostic and enthusiasts. therapeutic techniques proliferated and entered the mainstream of medicine, not without some Diagnostic endoscopy controversy. Success resulted in a huge service demand, with the need to train more endo- The first truly flexible gastroscope was developed in 1 This paper is scopists and to organise large endoscopy units the USA, following pioneering work on fibre-optic 2 based on the Lilly and teams of staff. The British health service light transmission in the UK by Harold Hopkins. Lecture given at struggled with insufficient numbers of consul- However, commercial production of endoscopes was the Royal College tants, other staff and resources, and British rapidly dominated by Japanese companies, building of Physicians on endoscopy fell behind that of most other devel- on their earlier expertise with intragastric cameras. 12 April 2005 by oped countries. This situation is now being My involvement began in 1968, whilst doing bench Peter B Cotton addressed aggressively, with many local and research with Dr Brian Creamer at St Thomas’ MD FRCP FRCS, national initiatives aimed at improving access and Hospital, London. An expert in coeliac disease (and Medical Director, choice, and at promoting and documenting jejunal biopsy), he opined that gastroscopy might Digestive Disease quality. Many more consultants are needed and become useful and legitimate only if it became pos- Center, Medical some should be relieved of their internal medi- sible to take target biopsy specimens – since no one University of South Carolina, cine commitment to focus on their specialist seriously believed what endoscopists said that they Charleston, USA skills. -

Duodenal Perforation Caused by Eyeglass Temples: a Case Report

Case Report Annals of Clinical Case Reports Published: 27 Jan, 2020 Duodenal Perforation Caused by Eyeglass Temples: A Case Report Zhiyong Dong1#, Wenhui Chen1#, Jin Gong1, Juncan Zhang1, Hina Mohsin2 and Cunchuan Wang1* 1Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, China 2Department of Neurology, California University of Science and Medicine, USA #These authors contributed equally to this work Abstract Background: While some foreign bodies in the digestive system can be egested spontaneously or after ingesting lubricants, generally long, large, sharp, irregularly shaped, hardened and/or toxic foreign bodies frequently remain in the digestive system. These foreign bodies may cause obstruction or damage the gastrointestinal mucosa leading to bleeding, perforation, and/or acute peritonitis, and may even cause local abscess, fistula formation, or organ damage. Case Report: A 30-year-old Chinese man was presented with acute abdominal pain while intoxicated with alcohol and swallowed two eyeglass temples. Conservative measures including ingesting lubricants to egest the foreign bodies failed. He underwent two exploratory laparotomy that showed a duodenal perforation and eventually the two eyeglass temples retrieved. Conclusion: This is the first report describing a patient who had swallowed eyeglass temples. Patients who swallow such objects must be promptly examined and diagnosed by ultrasound, X-ray, and/or CT, and foreign bodies removed by laparoscopy or laparotomy. Keywords: Duodenal perforation; Foreign body; Exploratory laparotomy OPEN ACCESS Introduction *Correspondence: Cunchuan Wang, Department of The effects of foreign bodies in the digestive system depend on their texture, shape, size, toxicity, Gastrointestinal Surgery, The First retention site, and duration [1]. Report of foreign bodies includes dentures, glass beads, coins, pens, Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, fish bones [2]. -

Isolated Left Hepatic Duct Injury in Blunt Trauma Abdomen: Two Case Reports with Literature Review

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 13, Issue 11 Ver. IV (Nov. 2014), PP 22-25 www.iosrjournals.org Isolated Left Hepatic Duct Injury in Blunt Trauma Abdomen: Two Case Reports with Literature Review Abhishek gupta, Tanmay jain, Mahakshit bhatt, Jitendra mangtani, K K dangayach Mahatma gandhi hospital,jaipur Abstract Isolated extrahepatic biliary tract injury following blunt abdominal trauma is rare. The underlying pathogenic mechanisms remain obscure, but include shear and/or compression forces on the biliary system. Associated morbidity rates are high and largely the result of delays in diagnosis. The primary aim of this paper is to describe the clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of two patients with left hepatic duct injury after blunt abdominal trauma. As a secondary objective, a literature review is presented. The two cases presented in this study are as follows: (1) A young male, involved in a crush injury by a motor vehicle, was referred with history of blunt hepatic trauma thirty days back and abdominal distension from a general hospital. His vitals were stable. Sonography of abdomen demonstrated a large fluid collection in upper abdomen. A percutaneous drain was placed in this collection and drained approximately 5000ml of bile. Due to continued drainage of several hundred millilitres of bile per day an Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) was obtained. This demonstrated a leakage at the left hepatic duct and stenting was done. Over the next several days, the drainage markedly decreased. A repeat ERCP was conducted 12 weeks later and stent was replaced. -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

Pneumatosis Intestinalis in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients

1997 Review Article Pneumatosis intestinalis in solid organ transplant recipients Vincent Gemma1, Daniel Mistrot1, David Row1, Ronald A. Gagliano1, Ross M. Bremner2, Rajat Walia2, Atul C. Mehta3, Tanmay S. Panchabhai2 1Department of Surgery, 2Norton Thoracic Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ, USA; 3Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Respiratory Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: D Row, RA Gagliano, TS Panchabhai; (II) Administrative support: RM Bremner, R Walia; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: V Gemma, D Mistrot, TS Panchabhai; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: V Gemma, D Mistrot, TS Panchabhai; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: RA Gagliano, RM Bremner, R Walia, AC Mehta, TS Panchabhai; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Tanmay S. Panchabhai, MD, FCCP. Associate Director, Pulmonary Fibrosis Center/Co-Director, Lung Cancer Screening Program, Norton Thoracic Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ, USA; Associate Professor of Medicine, Creighton University School of Medicine, Omaha, NE, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) is an uncommon medical condition in which gas pockets form in the walls of the gastrointestinal tract. The mechanism by which this occurs is poorly understood; however, it is often seen as a sign of serious bowel ischemia, which is a surgical emergency. Since the early days of solid organ transplantation, PI has been described in recipients of kidney, liver, heart, and lung transplant. Despite the dangerous connotations often associated with PI, case reports dating as far back as the 1970s show that PI can be benign in solid organ transplant recipients. -

Cecostomy Tube Lavage for Treatment of Fulminant Clostridium Difficile

Surgical Case Reports and Reviews Case Report ISSN: 2516-1806 Cecostomy tube lavage for treatment of fulminant clostridium difficile colitis in a recent transplanted patient Stephanie Pannell1*, Marcus Adair2, Katie Korneffel2, Bradley Gehring2, Daniel Rospert2, Jorge Ortiz2 and Munier Nazzal2 1Department of Surgery, 3064 Arlington Ave Toledo, OH 43614, USA 2Department of Surgery, University of Toledo College of Medicine & Life Sciences, USA Abstract Fulminant Clostridium Difficile Colitis (FCDC) is a highly lethal disease with mortality rates ranging between 12% - 80%. In patients status-post allograft solid organ transplant this rate is increased. Treatment, however, is the same as the general population; emergent exploratory laparotomy and subtotal colectomy. However, this procedure done in an emergent setting carries a mortality rate up to 34% as well as significant patient morbidity. To our knowledge, only a few studies have examined a less aggressive treatment. The technique involves creating a divergent ileostomy to deliver antibiotics directly into the colon. This patient, a 68 year- old male who underwent renal transplant 7 days earlier, developed abdominal distension and paralytic ileus with eventual diarrhea. C. difficile was confirmed by microbiological studies. Despite treatment with oral vancomycin and intravenous metronidazole, this patient developed sepsis and required laparotomy. The index case was complicated by cardiac arrest and aborted. Because of the poor clinical course, he underwent placement of cecostomy tube followed by antibiotic irrigation. Full recovery was achieved and complete anatomy of the colon was preserved. In patients with FCDC, less aggressive surgical options should be investigated, as they could have benefits on the subsequent quality of life of the patient. -

Strangulation of Upper Jejunum in Subsequent Pregnancy Following Gastric Bypass Surgery

■ CASE REPORT ■ STRANGULATION OF UPPER JEJUNUM IN SUBSEQUENT PREGNANCY FOLLOWING GASTRIC BYPASS SURGERY Chen-Bin Wang*, Ching-Chuan Hsieh1, Chun-Hung Chen, Yu-Hsiang Lin, Chung-Yuan Lee, Chih-Jen Tseng Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and 1General Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chia Yi, Taiwan. SUMMARY Objective: Gastric bypass is a surgical procedure that is popularly used to treat morbid obesity. Herein, we report a woman who had a rare gastrointestinal complication during the subsequent antepartum period following a gastric bypass surgery. Case Report: After a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, a 32-year-old woman had unrelenting epigastria for one week at 36 weeks’ gestation. An emergency cesarean delivery, followed by laparotomy, was performed. A female neonate was delivered with Apgar scores of 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. Strangulation and gangrene of the upper jejunum caused by a fibrous band at the site of the Roux anastomosis were revealed. Segmental resection of the nonviable bowel was performed. The patient experienced a smooth postoperative course. Conclusion: The awareness of internal hernias and small bowel strangulation should be addressed when unre- lenting epigastric pain is present in women after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, during their first subsequent pregnancy. [Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2007;46(3):267–271] Key Words: gastric bypass surgery, pregnancy complication, strangulation Introduction at lowering body weight and raising pregnancy rate, it is associated with some morbidity and complications. The incidence of obesity is rising globally at an alarming This article reports on a young woman treated with rate [1]. -

Development of the ICD-10 Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS)

Development of the ICD-10 Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS) Richard F. Averill, M.S., Robert L. Mullin, M.D., Barbara A. Steinbeck, RHIT, Norbert I. Goldfield, M.D, Thelma M. Grant, RHIA, Rhonda R. Butler, CCS, CCS-P The International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS) has been developed as a replacement for Volume 3 of the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-9-CM). The development of ICD-10-PCS was funded by the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).1 ICD-10- PCS has a multiaxial seven character alphanumeric code structure that provides a unique code for all substantially different procedures, and allows new procedures to be easily incorporated as new codes. ICD10-PCS was under development for over five years. The initial draft was formally tested and evaluated by an independent contractor; the final version was released in the Spring of 1998, with annual updates since the final release. The design, development and testing of ICD-10-PCS are discussed. Introduction Volume 3 of the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) has been used in the U.S. for the reporting of inpatient pro- cedures since 1979. The structure of Volume 3 of ICD-9-CM has not allowed new procedures associated with rapidly changing technology to be effectively incorporated as new codes. As a result, in 1992 the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) funded a project to design a replacement for Volume 3 of ICD-9-CM.