Andrew Lees, Campaigner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weavers' Way Short Walk 10 (Of 11) Halvergate to Berney Arms

S10 Weavers’ Way Short Walk 10 (of 11) Halvergate to Berney Arms www.norfolktrails.co.uk Version Date: December 2013 Along the way Walk summary A walk through the flat open landscape of Halvergate Marshes, rich with wildlife and windmills, that ends at one of the most The route begins in the village of Halvergate and leads along Marsh Road past the thatched Red remote railway stations in the country. Lion pub out onto the Halvergate Marshes. The marshes were part of a great estuary in Roman times but the area was drained and settled in the early medieval period and now makes up the Getting started largest expanse of grazing marsh in East Anglia. The whole area is designated as a site of This walk starts in Halvergate at Squires special scientific interest and has several international designations too. The marshes support Road/Marsh Road junction (TG420069) and ends internationally important numbers of wintering Bewick’s swan and populations of other waders at Berney Arms rail station (TG460053). and wildfowl that include ruff, golden plover, lapwing, bean goose, European white-fronted goose and wigeon. Other species breeding on Halvergate Marshes include snipe, oystercatcher, yellow Getting there Train Berney Arms Rail Station request stop on wagtail and bearded tit; short-eared and barn owls are frequent winter visitors. limited service. More trains on Sundays. National Rail enquiries: 08457 484950. A little less than a mile out of Halvergate, the Weavers’ Way leads away from the road and along www.nationalrail.co.uk a path to cross Halvergate Fleet, a salt marsh watercourse that the former road to Yarmouth Bus service used to run along until the construction of the Acle New Road (Acle Straight) in the 1830s. -

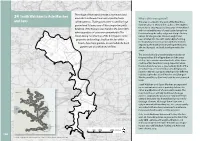

24 South Walsham to Acle Marshes and Fens

South Walsham to Acle Marshes The village of Acle stands beside a vast marshland 24 area which in Roman times was a great estuary Why is this area special? and Fens called Gariensis. Trading ports were located on high This area is located to the west of the River Bure ground and Acle was one of those important ports. from Moulton St Mary in the south to Fleet Dyke in Evidence of the Romans was found in the late 1980's the north. It encompasses a large area of marshland with considerable areas of peat located away from when quantities of coins were unearthed in The the river along the valley edge and along tributary Street during construction of the A47 bypass. Some valleys. At a larger scale, this area might have properties in the village, built on the line of the been divided into two with Upton Dyke forming beach, have front gardens of sand while the back the boundary between an area with few modern impacts to the north and a more fragmented area gardens are on a thick bed of flints. affected by roads and built development to the south. The area is basically a transitional zone between the peat valley of the Upper Bure and the areas of silty clay estuarine marshland soils of the lower reaches of the Bure these being deposited when the marshland area was a great estuary. Both of the areas have nature conservation area designations based on the two soil types which provide different habitats. Upton Broad and Marshes and Damgate Marshes and Decoy Carr have both been designated SSSIs. -

Broads (2006) IDB Water Level Management Plans: Summary

Broads (2006) IDB Water Level Management Plans: Summary WLMP Date reviewed Agreed (Lou WLMP Title (with Author Board Designated Site Designation Mayer/Clive English Doarks) Nature) SSSI, SAC, SPA, Calthorpe Broad RAMSAR, Heidi Brograve 2001 2005 Broads IDB NNR Mahon SSSI, SAC, Upper Thurne Broads SPA, & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Mike Upper Thurne Broads Catfield 2001 2005 Broads IDB SPA, Harding & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Mike Chapelfield 2001 2005 Broads IDB Ant Broads & Marshes SPA, Harding RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Halvergate Marshes , SPA, RAMSAR, Heidi SSSI, SAC, Mahon / Halvergate 2000 2005 Broads IDB Damgate Marshes SPA, Sandie RAMSAR, Tolhurst SSSI, SAC, Decoy Carr , SPA, RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Burgh Common SPA, Muckfleet Marshes RAMSAR, Hemsby and John 2000 2005 Broads IDB SSSI, SAC, Muckfleet Harpley Hall Farm Fen SPA, RAMSAR Trinity Broads SSSI, SAC SSSI, SAC, Priory Meadows , SPA, Heidi RAMSAR, Hickling 2001 2005 Broads IDB Mahon SSSI, SAC, Upper Thurne Broads SPA, & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Horning 1998 2005 Broads IDB Alderfen Broad SPA, Harpley RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Ludham – Potter SPA, Horsefen 1999 2005 Broads IDB Harpley Heigham Marshes RAMSAR, NNR SSSI, SAC, Upper Thurne Broads SPA, John & Marshes Horsey 2000 2005 Broads IDB RAMSAR,s Harpley Winterton To Horsey SSSI, SAC Dunes SSSI, SAC, Ludham Bridge John 1999 2005 Broads IDB Ant Broads & Marshes SPA, East Harpley RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Upper Thurne Broads Martham 2002 2005 Broads IDB SPA, Harpley & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Ludham – Potter SPA, Potter Heigham -

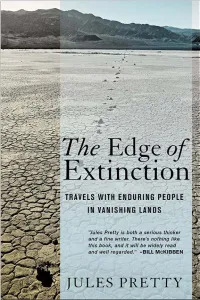

The Edge of Extinction: Travels with Enduring People in Vanishing

THE EDGE OF EXTINCTION Th e Edge of Extinction TRAVELS WITH ENDURING PEOPLE IN VANISHING LANDS M jules pretty Comstock Publishing Associates a division of Cornell University Press Ithaca and London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pretty, Jules N., author. Th e Edge of extinction : travels with enduring people in vanishing lands / Jules Pretty. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8014-5330-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Nature—Eff ect of human beings on—Moral and ethical aspects. 2. Human beings—Eff ect of environment on—Moral and ethical aspects. I. Title. GF80.P73 2014 304.2—dc23 2014017464 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fi bers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu . Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 { iv } For My father, John Pretty (1932–2012), and mother, Susan and Gill, Freya, and Th eo Without my journey And without this spring I would have missed this dawn. -

Norton Marshes to Haddiscoe Dismantled

This area inspired the artist Sir J. A. Arnesby 16 Yare Valley - Norton Marshes to Brown (1866-1955) who lived each summer Haddiscoe Dismantled Railway at The White House, Haddiscoe. Herald of the Night, Sir J.A.Arnesby-Brown Why is this area special? This is a vast area of largely drained marshland which lies to the south of the Rivers Yare and Waveney. It traditionally formed part of the parishes of Norton (Subcourse), Thurlton, Thorpe and Haddiscoe along with a detached part of Raveningham. It would have had a direct connection to what is now known as Haddiscoe Island, prior to the construction of the New Cut which connected the Yare and Waveney together to avoid having to travel across Breydon Water. There are few houses within this marshland area. Those that exist are confined to those locations 27 where there were, or are transport links across NORFOLK the rivers. The remainder of the settlements have 30 28 developed in a linear way hugging the edges of the southern river valley side. 22 31 23 29 The Haddiscoe Dam road provides the main 24 26 connection north-south from Haddiscoe village to 25 NORWICH St Olaves. 11 20 Gt YARMOUTH 10 12 19 21 A journey on the train line from Norwich to 14 9 Lowestoft which follows the line of the New Cut 13 15 18 16 and then hugs the northern side of the Waveney 17 Valley provides a glorious way to view this area as 8 7 public rights of way into the middle of the marshes LOWESTOFT 6 4 (other than the fully navigable river) are few and 2 3 1 5 far between. -

NPS Property Consultants

Acle Road, Norwich of North Land / Habitats Regulations Assessment Assessment Regulations Habitats / Report for for Report NPS Property Consultants Property Acle Road, Norwich of North Land Land North of Norwich Road, Acle / Habitats Regulations Assessment Assessment Regulations Habitats NPS Property Consultants / Report for for Report NP S Author Graham Hopkins BSc (Hons) PhD PGCE FRES CEnv MCIEEM Consultants Property Job No. 140961/ 6396 Reviewed by Approved by Date Initial Alex Prendergast Danny Thomas 03/09/14 Revised Dr Rachel Saunders Tracy Simpson 10/10/17 The Ecology Consultancy Thorpe House, 79 Thorpe Road, Norwich, NR1 1UA T. 01603 628408 E. [email protected] W. www.ecologyconsultancy.co.uk Contents Executive Summary 1 1 Introduction 4 2 Background HRAs 6 3 Disturbance Impacts and Visitor Origins 7 4 Available Recreation Resources Locally 13 5 Refined List of Scoped-In Sites and Footpaths 19 6 Stage 1: Tests of Likely Significant Effects 24 7 In-Combination Effects 27 References 28 Appendix 1: Legislation and Process 31 Appendix 2: Background Information 36 Appendix 3: Figures 41 LIABILITY The Ecology Consultancy has prepared this report for the sole use of the commissioning party in accordance with the agreement under which our services were performed. No warranty, express or implied, is made as to the advice in this report or any other service provided by us. This report may not be relied upon by any other party without the prior written permission of The Ecology Consultancy. The content of this report is, at least in part, based upon information provided by others and on the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has been requested. -

Biodiversity Action Plan

BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN April 2018 BROADS IDB – BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN Front cover images (L-R) Marsh Harrier ©Artur Rydzewski; Norfolk Hawker © Milo Bostock; Water Soldier; Water Vole; Berney Marshes ©Mike Page; BIDB Digger BROADS IDB – BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN FOREWORD This Biodiversity Action Plan (Second Edition) has been prepared by the Broads Internal Drainage Board in accordance with the commitment in the Implementation Plan of the DEFRA Internal Drainage Board Review for IDB’s, to produce their own Biodiversity Action Plans by April 2010. As such, the original version was published in January 2010. This revised version aims to continue to align the Broads IDB with biodiversity policy and more specifically, the Biodiversity document for England, “Biodiversity 2020: A strategy for Englands’ Wildlife and Ecosystem Services” and build on the Government’s 25 Year Environmental Plan; A Green Future. In doing so, the document strives to demonstrate the Board’s commitment to fulfilling its duty as a public body under the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006 to conserve biodiversity. Many of the Board’s activities have benefits and opportunities for biodiversity, not least its water level management and watercourse maintenance work. It is hoped that this Biodiversity Action Plan will help the Board to maximise the biodiversity benefits from its activities and demonstrate its contribution to the targets as part of the Biodiversity 2020 strategy and achieve wider environmental improvement within its catchments. The Board has adopted the Biodiversity Action Plan as one of its policies and subject to available resources is committed to its implementation. It will review the plan periodically and update it as appropriate. -

Habitats Regulations Assessment: Draft Scoping Report

North Norfolk 2016 - 2036 HABITATS REGULATIONS ASSESSMENT Draft Scoping Report May 2017 North Norfolk District Council Planning Policy Team Telephone: 01263 516318 E-Mail: [email protected] Write to: Planning Policy Manager, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, NR27 9EN www.north-norfolk.gov.uk/localplan All documents can be made available in Braille, audio, large print or in other languages. Please contact 01263 516318 to discuss your requirements. Draft HRA Scoping - North Norfolk District Council – Emerging Local Plan Executive Summary Habitats Regulations Assessment is required in accordance with the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010, (amended 2012); in order to ensure that plans and projects do not have a likely significant effect on any European designated sites for nature conservation. Such plans or projects can only proceed if the competent authority is convinced they will not have an “adverse effect on the integrity of a European site”. Where there is uncertainty over the effects then the competent authority will need to demonstrate how these can be avoided and what mitigation can be put in place. A Local Plan is the subject of Habitats Regulations Assessment, which is the responsibility of the plan-making body (in this case North Norfolk District Council) to produce. This scoping report provides the background and review of evidence to support the commencement of screening and the final Habitats Regulations Assessment of the North Norfolk Core Strategy and Site Allocations documents. This report considers: • The European designated sites within and outside the plan area affected. • The characteristics of these sites and their conservation objectives. -

Weavers' Way Long Walk 4 (Of 4) Acle to Great Yarmouth

L4 Weavers’ Way Long Walk 4 (of 4) Acle to Great Yarmouth www.norfolktrails.co.uk Version Date: December 2013 Along the way Walk summary This walk begins with paths and lanes through arable farmland before crossing the flat, open From Acle, the route crosses Damgate Marshes to reach the small village of Tunstall and then, a landscape of Halvergate Marshes and following th the north bank of Breydon Water to reach the little further on, Halvergate, where the 13 century church of St Peter and St Paul dominates the historic seaside resort of Great Yarmouth. village with its tall tower. Leaving Halvergate, the route leads out onto the Halvergate Marshes, which were part of a great estuary in Roman times but now make up the largest expanse of Getting started grazing marsh in East Anglia. The marshes support an important winter population of Bewick’s This walk starts at Acle Dyke (TG409107) and swan as well as many other wintering waders and wildfowl. The route continues to reach the ends at Great Yarmouth rail station (TG520081) Berney Arms railway station, an isolated railway halt on the line between Norwich and Great also the starting point of Wherryman’s Way and Yarmouth that is only accessible by rail, boat or foot. The station takes its name from Thomas Angles Way. Trench Berney, a local landowner who sold the land to the railway company on the condition that Getting there they provided a stopping place in perpetuity. Coach National Express 308, 490 & 491. National express enquires: 08717 818178 Reaching the River Yare at Berney Arms Mill, the way joins with the route of the Wherryman’s www.nationalexpress.com Train Acle and Great Yamrouth Rail Stations Way and continues past the Berney Arms public house (seasonal opening) to arrive at the National Rail enquiries: 08457 484950 confluence with the River Waveney and the beginning of Breydon Water, a tidal estuary that www.nationalrail.co.uk flows into the sea at Great Yarmouth. -

The Norfolk & Norwich

TRANSACTIONS OF THE NORFOLK & NORWICH NATURALISTS' SOCIETY VOL. XXIII 1974 - 1976 LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS Page Allard, P. R. 29 Banham, P. R. 145 Buckley, J 86,172 Funnell, B.M 251 Gosling, L. M 49 Gurney, C Ill Harding, P. T 267 Harrison, R. H 45 Hornby, R 231 Ismay, J 231, 271 Kington, J. A. 140 Lambley, P. W 170, 231, 269, 270 Norgate, T. B 167 Oliver, J 120 Peet, T. N.D 156,249 Ramsay, H. R. 28 Watts, G. D 231 Williams, R. B 257 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS (Plates adjoin pages indicated) Bat, Long-eared 60 Bearded Tit 95 Bewick's Swan ••• 103 Black-bellied Dipper ... ... ... ••• ••• ••• ••• 44 Black-headed Gull 29 Black-tailed Godwit ... ... ... ••• ••• ••• ••• 87 Common Tern ••• 94 Curlew ••• 216 Deer, Roe 61 Page Green Sandpiper ... ... ... 216 Hawfinch 79 Heron Hortus Sanitatus, figures from 117 Kingfisher 200 Knot 28 Lapwing 102 Little Egret 12 Little Ringed Plover ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 29 Osprey 102 Pied Flycatcher 44 217 Pyiausta peilucidalis 249 Red-breasted Flycatcher ... ... 44 Salt Pans 150-151 Sandwich Tern 28,201 Short-eared Owl ... ... ... ... ... 45 Snipe 200 Sparrowhawk 44 Squirrel, Grey 60 Water-rail 13 Waxwing 78,201 Weather Maps, Europe, 1784 143- 144 White-fronted Goose 45 Wryneck 217 Yare Valley 247 - 249 INDEX TO VOLUME XXIII Amphibia and Reptile Records for Norfolk ... ... 172 Barton Broad, Bird Report ... ... ... ... 5 Bird Report, Classified Notes 1972 30 1973 96 1974 202 Bird Report, Editorial 1972 2 1973 71 1974 194 Bird Ringing Recoveries 22, 92, 197 Birds and the Weather of 1784 140 Blakeney Point, Bird Report 5 Breydon Water, Bird Report .. -

Proposed Mineral Extraction Sites

Proposed Mineral Extraction Sites 104 Breckland Sites Map of proposed sites in Beetley (MIN 08, MIN 12, MIN 13, MIN 51) MIN 12 - land north of Chapel Lane, Beetley Site Characteristics • The 16.38 hectare site is within the parish of Beetley • The estimated sand and gravel resource at the site is 1,175,000 tonnes • The proposer of the site has given a potential start date of 2025 and estimated the extraction rate to be 80,000 tonnes per annum. Based on this information the full mineral resource at the site could be extracted within 15 years, therefore approximately 960,000 tonnes could be extracted within the plan period. • The site is proposed by Middleton Aggregates Ltd as an extension to an existing site. • The site is currently in agricultural use and the Agricultural Land Classification scheme classifies the land as being Grade 3. • The site is 3.7km from Dereham and 12km from Fakenham, which are the nearest towns. • A reduced extraction area has been proposed of 14.9 hectares, which creates standoff areas to the south west of the site nearest to the buildings on Chapel Lane, and to the north west of the site nearest the dwellings on Church Lane. Amenity: The nearest residential property is 11m from the site boundary. There are 21 sensitive receptors within 250m of the site boundary. The settlement of Beetley is 260m away and Old Beetley is 380m away. However, land at the north-west and south-west corners is not proposed to be extracted. Therefore the nearest residential property is 96m from the extraction area and there are 18 sensitive receptors within 250m of the proposed extraction area. -

Broads Authority Agenda Papers 24 July 2020

Broads Authority Agenda 24 July 2020 10.00am This is a remote meeting held under the Broads Authority’s Standing Orders on Procedure Rules for Remote Meetings. Participants: You will be sent a link to join the meeting. The room will open at 9.00am and we request that you log in by 9.30am to allow us to check connections and other technical details. Members of the public: We will publish a live stream link two days before the meeting at Broads Authority 24 July 2020. The live stream will be suspended for any exempt items on the agenda. Please email [email protected] with any queries about this meeting. Introduction 1. To receive apologies for absence 2. Chairman’s announcements 3. Introduction of members and declarations of interest 4. To note whether any items have been proposed as matters of urgent business 5. Public question time – to note whether any questions have been raised by members of the public 6. To receive and confirm the minutes of the Broads Authority meeting held on 25 June 2020 (Pages 3-9) 7. Summary of actions and outstanding issues following decisions at previous meetings – to note the schedule (Pages 10-16) Strategy and policy 8. Climate Change Action Plan (Pages 17-30) Report by Carbon Reduction Project Manager 9. Draft Statement of Account 2019/20 (Pages 31-120) Report by Chief Financial Officer 10. Strategic Direction and Annual Business Plan (Pages 121-171) Report by Head of Governance Broads Authority, 24 July 2020 11. Statement of Community Involvement – revision for adoption in response to COVID-19 restrictions (Pages 172-213) Report by Planning Policy Officer 12.