Marine Ecology Progress Series 328:1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Life History of Tropical and Temperate Sepioteuthis Squids in Australian Waters

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Pecl, Gretta T. (2000) Comparative life history of tropical and temperate Sepioteuthis squids in Australian waters. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/24094/ If you believe that this work constitutes a copyright infringement, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/24094/ CHAPTER 4: FLEXIBLE REPRODUCTIVE STRATEGIES IN TROPICAL AND TEMPERATE SEPIOTEUTIDS SQUIDS 4.1 INTRODUCTION An individuals' "fitness" in the evolutionary sense, is determined by both absolute fecundity and generation interval (Roff 1986). Both of these life history traits are dependent on the reproductive strategy of a species, and indeed are likely to be divergent between those species or individuals that breed once and die, and those that breed over an extended time frame. Optimal age or size at maturity and the associated age- and size specific schedules of reproductive investment are just some of the life history characteristics that are also intimately related to the reproductive strategy of a species (Stearns 1977). As a consequence of the very short life span typical of most cephalopods, annual recruitment is essential to sustain populations (Boyle 1990). and as such an understanding of the reproductive strategy of a cephalopod fisheries resource is crucial. Determining how long an individual takes to complete egg maturation and deposition, and assessing what portion of the life span this period represents, is a major difficulty confronting detailed examinations of cephalopod reproductive biology in field populations (Collins el at. 1995b). Although coleoid cephalopods have traditionally been viewed as semelparous organisms that reproduce once and die (Arnold & Williams-Arnold 1977; Calow 1987; eg: lllex illecebrosus O'Dor 1983; Todarodes pacijicus Okutani 1983), it is becoming increasingly apparent that many species are not restricted to thi s strategy. -

Fishing Today Tasmanian Seafood Industry News

FISHING TODAY TASMANIAN SEAFOOD INDUSTRY NEWS Volume 26 No 4 August/September 2013 The 4th Tasmanian SeafoodAwards Industry INSIDE: > New seal protection pens P 3 > 2013 Commercial Scallop Season P 9 > Hobart research hub P 26 Domain Slipway The Domain Slipway is Tasmania’s best located and The Domain Slipway oers: rst environmentally compliant slipway. The No. 1 • competitive rates Slipway supports large shing boats, mega (super) yachts and tug boats up to 2000 tonnes with multiple • equipment hire slipping potential. • water and grit equipment The No. 2 and 3 slips cater for a maximum of 180 tonne and 50 tonne vessels respectively. • highly experienced Marine Engineers For bookings and enquiries: The Domain Slipway also provides 24 hour, seven Phone 0428 903 149 days a week access to a marine fuelling facility. • assistance with vessel docking and labour sourcing Email [email protected] > AUSTRALIAN PUMP INDUSTRIES Safe under pressure Aussie Pumps, Australia’s leading times stronger than steel on a weight- Aussie Pumps’ Product Safety Manager, manufacturer of high pressure water for-weight basis. Martine Musumeci said: ‘Considering blasting equipment, has released a The range of Aussie “Safe Operator” that ninety per cent of all professional new range of high pressure protection clothing includes overalls, jackets, pressure cleaning is carried out in the clothing. Designed for use with pressure trousers and aprons, and the gear is range of under 500 bar (that’s 7300psi), cleaners up to 7300 psi (500 bar), much thinner and more flexible than operators using machines in the 2000 psi Aussie’s new “Safe Operator” range traditional materials. -

New TRLPA Board Tasmanian Gould's Squid Fishery Investigating

FISHINGTasmanian seafood TODAYindusTry news New TRLPA Board Page 3 Tasmanian Gould’s Squid Fishery Page 8 Investigating areas for sevengill sharks Page 27 Volume 27 Volume No 4 August/September 2014 Seafood Directions 2015 Selling Our Story Australian Seafood Industry National Conference 2015 The seafood industry has an important story to sell Crown Perth • Perth, WA • 25th - 27th October and the next chapter will be written at Seafood Directions 2015. insight and make invaluable connections. So book your berth in Perth and we look forward to seeing Our future depends on new ways of marketing, you at Seafood Directions 2015. gaining social licence to operate and increased collaboration and communication with government, For information, sponsorship and exhibition regulators, customers and community. opportunities contact: With keynote presentations on the industry’s T: (+61) 7 4031 2345 future and practical workshops to make that future E: [email protected] happen, seafood professionals will gain valuable W: www.seafooddirections.net.au FishingTODAY_120x186_2014June_1.indd 1 13/05/14 11:45 AM Domain Slipway The Domain Slipway is Tasmania’s best located and The Domain Slipway oers: rst environmentally compliant slipway. The No. 1 • competitive rates Slipway supports large shing boats, mega (super) yachts and tug boats up to 2000 tonnes with multiple • equipment hire slipping potential. • water and grit equipment The No. 2 and 3 slips cater for a maximum of 180 tonne and 50 tonne vessels respectively. • highly experienced Marine Engineers For bookings and enquiries: The Domain Slipway also provides 24 hour, seven Phone 0428 903 149 days a week access to a marine fuelling facility. -

Comparative Life History of Tropical and Temperate Sepioteuthis Squids in Australian Waters

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Pecl, Gretta T. (2000) Comparative life history of tropical and temperate Sepioteuthis squids in Australian waters. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/24094/ If you believe that this work constitutes a copyright infringement, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/24094/ COMPARATIVE LIFE mSTORY OF TROPICAL AND TEMPERATE SEPIOTEUTHIS SQUIDS IN AUSTRALIAN WATERS. Thesis submitted by Gretta T. Peel (Hons.) (JeU) October 2000 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Marine Biology within the School of Marine Biology and Aquaculture James Cook Uni versity STATEMENT OF ACCESS I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other photographic means. allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: "In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part, or use the results in any other work (written or otherwise) without the signed consent of the author; and to make proper written acknowledgment for any other assistance which I have obtained from it." Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. ..... 9JQ:.cc .. DECLARA TION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any fOIm for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. -

Defensive Behaviors of Deep-Sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy

Defensive Behaviors of Deep-sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy by Stephanie Lynn Bush A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Roy L. Caldwell, Chair Professor David R. Lindberg Professor George K. Roderick Dr. Bruce H. Robison Fall, 2009 Defensive Behaviors of Deep-sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy © 2009 by Stephanie Lynn Bush ABSTRACT Defensive Behaviors of Deep-sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy by Stephanie Lynn Bush Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Roy L. Caldwell, Chair The deep sea is the largest habitat on Earth and holds the majority of its’ animal biomass. Due to the limitations of observing, capturing and studying these diverse and numerous organisms, little is known about them. The majority of deep-sea species are known only from net-caught specimens, therefore behavioral ecology and functional morphology were assumed. The advent of human operated vehicles (HOVs) and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) have allowed scientists to make one-of-a-kind observations and test hypotheses about deep-sea organismal biology. Cephalopods are large, soft-bodied molluscs whose defenses center on crypsis. Individuals can rapidly change coloration (for background matching, mimicry, and disruptive coloration), skin texture, body postures, locomotion, and release ink to avoid recognition as prey or escape when camouflage fails. Squids, octopuses, and cuttlefishes rely on these visual defenses in shallow-water environments, but deep-sea cephalopods were thought to perform only a limited number of these behaviors because of their extremely low light surroundings. -

Population Dynamics and Reproductive Ecology of the Southern Calamary in Tasmania

FRDC FINAL REPORT POPULATION DYNAMICS AND REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY OF THE SOUTHERN CALAMARY (SEPIOTEUTHIS AUSTRALIS) IN TASMANIA Natalie Moltschaniwskyj, Gretta Pecl, Jeremy Lyle, Malcolm Haddon, & Michael Steer June 2003 FRDC Project No. 2000/121 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry Moltschaniwskyj, Natalie Ann, 1965- Population dynamics and reproductive ecology of the southern calamary (Sepioteuthis australis) in Tasmania. ISBN 1 86295 104 7 1. Squid fisheries - Tasmania. 2. Squids - Reproduction - Tasmania. I. Moltschaniwskyj, N. II. Tasmanian Aquaculture and Fisheries Institute. 639.485809946 Tasmanian Aquaculture and Fisheries Institute, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 49, Hobart, Tasmania 7001. E-mail: [email protected]. Ph. (03) 6227 7277 Fax (03) 6227 8035 The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author/s and are not necessarily those of the Tasmanian Aquaculture and Fisheries Institute. Tasmanian Aquaculture and Fisheries Institute, University of Tasmania 2003. Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without the prior written permission of the Tasmanian Aquaculture and Fisheries Institute. Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 List of Figures 4 List of Tables 9 Non-Technical Summary 12 Acknowledgements 16 Background 17 Need 18 Objectives 19 General Introduction 20 Chapter 1: Small-scale spatial and temporal patterns of egg production by the temperate loliginid squid Sepioteuthis -

Using Artificial-Reef Knowledge to Enhance the Ecological Function of Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations: Implications for Fish A

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Review Using Artificial-Reef Knowledge to Enhance the Ecological Function of Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations: Implications for Fish Abundance and Diversity Maria Glarou 1,2,* , Martina Zrust 1 and Jon C. Svendsen 1 1 DTU Aqua, Technical University of Denmark (DTU), Kemitorvet, Building 202, 2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark; [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (J.C.S.) 2 Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences, Stockholm University, Svante Arrhenius väg 20 A (or F), 114 18 Stockholm, Sweden * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +45-50174014 Received: 13 April 2020; Accepted: 5 May 2020; Published: 8 May 2020 Abstract: As the development of large-scale offshore wind farms (OWFs) amplifies due to technological progress and a growing demand for renewable energy,associated footprints on the seabed are becoming increasingly common within soft-bottom environments. A large part of the footprint is the scour protection, often consisting of rocks that are positioned on the seabed to prevent erosion. As such, scour protection may resemble a marine rocky reef and could have important ecosystem functions. While acknowledging that OWFs disrupt the marine environment, the aim of this systematic review was to examine the effects of scour protection on fish assemblages, relate them to the effects of designated artificial reefs (ARs) and, ultimately, reveal how future scour protection may be tailored to support abundance and diversity of marine species. The results revealed frequent increases in abundances of species associated with hard substrata after the establishment of artificial structures (i.e., both OWFs and ARs) in the marine environment. -

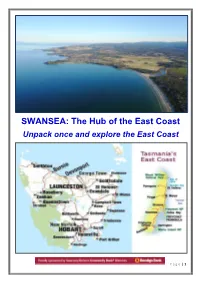

SWANSEA: the Hub of the East Coast Unpack Once and Explore the East Coast

SWANSEA: The Hub of the East Coast Unpack once and explore the East Coast P a g e | 1 A Leisurely Day in Swansea Locals love coming home to Swansea – we crest the hill near Kelvedon Beach and can feel the tension start to leave us. We want you to do the same – enjoy the slower pace, allowing yourself the time to relax and recharge! If you’re an early riser, this might mean catching a beautiful sunrise whilst walking along one of our many beaches all of which look out across Great Oyster Bay toward the Hazards at Coles Bay; soak up the peace and quiet and stop to take in the beauty. Swansea was settled in the 1820’s as Waterloo Point, and is one of Tasmania’s oldest towns. In fact many families living in Swansea today are descedants of these original settlers. Pop into the Visitor Information Centre and get a copy of the Heritage Walk booklet and you’ll be able to take a self-directed walk around town to learn about historical businesses, homes and iconic landmarks. You might even come across one of our older locals who’s willing to have a chat. You could also visit the East Coast Heritage Museum; there’s always a great display and passionate staff to share their knowledge. Stroll along Franklin Street (the main street) to find your perfect breakfast spot: - Barkmill Bakery, Artifakt Café & Gallery, Saltshaker. After breakfast, why not take a gentle walk right in the heart of Swansea; a walk that offers stunning coastal scenery. -

Farm Pond Management for Recreational Fishing

MP360 Farm Pond Management for Recreational Fishing Fis ure / herie ult s C ac en u te q r A Cooperative Extension Program, University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and U f County Governments in cooperation with the Arkansas n f i u v l e B Game and Fish Commission r e si n ty Pi of at Arkansas Farm Pond Management for Recreational Fishing Authors University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff Aquaculture and Fisheries Center Scott Jones Nathan Stone Anita M. Kelly George L. Selden Arkansas Game and Fish Commission Brett A. Timmons Jake K. Whisenhunt Mark Oliver Editing and Design Laura Goforth Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................................1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 The Pond Ecosystem .................................................................................................1 Pond Design and Construction Planning............................................................................................................................................2 Site Selection and Pond Design.......................................................................................................2 Construction…………………………………………………………………………… .............................3 Ponds for Watering Livestock..........................................................................................................3 Dam Maintenance ............................................................................................................................3 -

7 Days up the Tasmanian East Coast Day 1. Hobart

www.drivenow.com.au – helping travellers since 2003 find the best deals on campervan and car rental 7 Days up the Tasmanian East Coast Hobart Hobart to Port Arthur Port Arthur to Triabunna (Maria Island) Triabunna to Bicheno Bicheno to St Helens St Helens to Scottsdale Scottsdale to Launceston Distance: 582km Day 1. Hobart Pick up your campervan in Hobart today. Allow at least 1 – 1.5 hours in order to familiarise yourself with the vehicle before you leave the depot. Hobart is the capital city of Tasmania, which means that there is a wide variety of activities and attractions suited to everyone. Mount Wellington is about a 30-minute drive west of Hobart, and is a must-see when you visit Hobart. Journey to the summit of the mountain, and if it’s a clear day, you can sometimes see all the way to the Tasman Sea. For something a little more active, you can trek along one of the many paths or even bring your bike. The natural environment is perfect for adventurous explorers. Stay: Discovery Holiday Parks, Hobart. www.drivenow.com.au – helping travellers since 2003 find the best deals on campervan and car rental Day 2. Hobart to Port Arthur Depart this morning and take the A3 towards Bellerive. Turn right and follow Cole St/ A9 until you reach Port Arthur. Travel back to colonial Australia and visit the Port Arthur Historic Site, a World Heritage-listed attraction. Port Arthur was a penal settlement established in the 1830s, and was the home for many of the convicts that arrived from Britain. -

Clupea Harengus)

Cover images: Herring eggs in different developmental stages: shortly after fertilization in a petri dish (top), and advanced embryos attached to Zostera marina (right) and Fucus vesiculosus (bottom) on a natural spawning bed in the southern Baltic Sea. Effects of coastal habitat characteristics on the reproduction of Baltic herring (Clupea harengus) Dissertation with the aim of achieving a doctoral degree at the Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Natural Sciences Department of Biology Institute of Marine Ecosystem and Fishery Science University of Hamburg submitted by Lena von Nordheim 2019 in Hamburg Dissertation evaluation commission: Prof. Dr. Christian Möllmann, Institute of Marine Ecosystem and Fishery Science, University of Hamburg Dr. Patrick Polte, Thünen Institute of Baltic Sea Fisheries, Rostock Examination commission: Prof. PhD. Myron Peck (chair of commission), Institute of Marine Ecosystem and Fishery Science, University of Hamburg Prof. Dr. Christian Möllmann, Institute of Marine Ecosystem and Fishery Science, University of Hamburg Prof. Dr. Ralf Thiel, Department Ichthyology, Center of Natural History, University of Hamburg Dr. Patrick Polte, Thünen Institute of Baltic Sea Fisheries, Rostock Date of the oral defense: 05th December 2019 DISSERTATION EFFECTS OF COASTAL HABITAT CHARACTERISTICS ON THE REPRODUCTION OF BALTIC HERRING (Clupea harengus) CONTENTS SUMMARY 1 ZUSAMMENFASSUNG 5 GENERAL INTRODUCTION 9 MANUSCRIPT I - Influence of the macrophyte composition on spawning substrate selection behavior of spring spawning Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) in the Baltic Sea 31 MANUSCRIPT II - Developmental success of herring eggs spawned on different plant species 55 MANUSCRIPT III - Lethal effect of filamentous algal blooms on Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) eggs in the Baltic Sea 73 MANUSCRIPT IV - Impact of Spawning Substrate Complexity on Egg Survival of Atlantic Herring (Clupea harengus, L.) in the Baltic Sea. -

93/161 Tasmanian Scallops Pty Ltd Principal Inve

FINAL REPORT OF THE MARKETING AND TRANSPORTING OF LIVE SCALLOPS PROJECT NUMBER: 93/161 TASMANIAN SCALLOPS PTY LTD PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR NAME: HARUO MORIYA ADDRESS: PO BOX 50, TRIABUNNA, TASMANIA 7190 TELEPHONE: 002 573 614 FAX: 002 573 616 NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY The demand forli ve scallop is quite strong. The main customer of live scallop is restaurants. Restaurants require the freshness to attract their customer. Live scallop is good to impress the freshness. The freshness is the key word to add value to scallop product. The freshness of live scallop is indicated by the mortality. The company examined the effectof air exposure on mortality that arises from transporting. The company developedthe means of maintaining live scallop condition through the result of examination. The company introduced sea water cooling system for on-shore storage. Cultured scallop is attached by oyster, mussel, sea squirt and other marine life. It needs cleaning. The company used to do this by hand. The company introduced the shell cleaning machine. Economical advantage was tested by comparison between hand cleaning and machine cleaning. When transportingli ve scallop, insulation and keeping cool are important factor. The best combination of packing material is verifiedby examination. Scallop live market is still embryonic. The company requested the University of Tasmania to study overseas and domestic live scallop market. The company framed a marketing strategy through that study. BACKGROUND PROGRESS IN SCALLOPAQUACULTURE In 1967, D.C.Wolfeand J.F.Grant deployed spat collectors in Promise Bay on Tasmania's east coast. Although this work continued until 1973, no attempt was made to increase the scale of the work.