Specific Clinical Situations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTE: the Following Are Shirley Ryan Abilitylab's Standard Charges As of Jan. 1, 2019. These Standard Charges Often Do Not

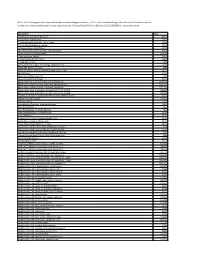

NOTE: The following are Shirley Ryan AbilityLab's standard charges as of Jan. 1, 2019. These standard charges often do not reflect what a patient or their insurance company/payer may be required to pay. Contact Patient Financial Services at 312-238-6039 for more information. Description Price 11-Deoxycortisol, Urine Random $531 12 Lead Ekg, Tracing Only $245 17 Hydroxycorticosteroids, Urine Timed $363 17 Hydroxyprogesterone, Serum $172 17 Ketosteroids, Urine Timed $273 17-Ketosteroids with Creatinine, Urine Random $273 2D Gait Analysis Charge(95999) $2,174 5' Nucleotidase, Serum $269 5.5 PDC PEDS CUFFED TRACH $226 5-HIAA-24 Hr Urine $99 A4566 Shoulder sling or vest design, abduction res $226 A4595 FES Electrode, each $38 A6545 Gradient Compression Wrap, Non-Elastic, Belo $171 ABO Rh Type $106 Above Knee Nylon Hose PR $83 Above Knee Suction Sheath $131 Above knee, for proximal femoral focal deficiency, $14,344 Above knee, molded socket, open end, SACH foot, en $10,751 Above knee, molded socket, single axis constant fr $10,935 Above knee, short prosthesis, no knee joint (""stu_L5210 $8,682 Above knee, short prosthesis, no knee joint (""stu_L5220 $7,429 ACAPELLA DH GREEN VIBRATORY PEP W/MOUTHPIECE DEVIC $181 Acetabuloplasty (27120) $4,493 Acetone, Serum $27 Acetylcholine Receptor Binding Antibody $405 Acid Phosphatase $66 Acid Phosphatase, Prostatic fraction $66 ACNE SURGERY MILIA CYSTS (10040) $530 Acorn Nebulizer $174 Activated PTT/Partial Thromboplastin Time $109 Active Wound Care > 20 cm Units $171 Active Wound Care/20 cm or < Units $171 Acupuncture with E-Stim. Each additional 15 minute $65 Acupuncture with E-Stim. -

Study Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Institutional Review Board PROJECT SUMMARY Study Title: Ultrasound-guided fascia iliaca compartment block versus periarticular infiltration for pain management after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial Principal Investigator: Irina Gasanova, MD Sponsor/Funding Source: Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Management, UT Southwestern Medical School IRB Number: STU 122015-022 NCT Number: NCT02658240 Date of Document: 01 April 2016 Page 1 of 7 Purpose: In this randomized, controlled, observer-blinded study we plan to evaluate ultrasound-guided fascia iliaca compartment block with ropivacaine and periarticular infiltration with ropivacaine for postoperative pain management after total hip arthroplasty (THA). Background: Despite substantial advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of pain and availability of newer analgesic techniques, postoperative pain is not always effectively treated (1). Optimal pain management technique balances pain relief with concerns about safety and adverse effects associated with analgesic techniques. Currently, postoperative pain is commonly treated with systemic opioids, which are associated with numerous adverse effects including nausea and vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness, pruritus, urinary retention, and respiratory depression (2). Use of regional and local anesthesia has been shown to reduce opioid requirements and opioid-related side effects. Therefore, their use has been emphasized (3, 4, 5, 6). Fascia Iliaca compartment block (FICB) is a field block that blocks the nerves from the lumbar plexus supplying the thigh (i.e., lateral femoral cutaneous femoral and obturator nerves). The obturator nerve is sometimes involved in the FICB but probably plays little role in postoperative pain relief for most surgeries of the hip and proximal femur. -

Could Mycolactone Inspire New Potent Analgesics? Perspectives and Pitfalls

toxins Review Could Mycolactone Inspire New Potent Analgesics? Perspectives and Pitfalls 1 2 3, 4, , Marie-Line Reynaert , Denis Dupoiron , Edouard Yeramian y, Laurent Marsollier * y and 1, , Priscille Brodin * y 1 France Univ. Lille, CNRS, Inserm, CHU Lille, Institut Pasteur de Lille, U1019-UMR8204-CIIL-Center for Infection and Immunity of Lille, F-59000 Lille, France 2 Institut de Cancérologie de l’Ouest Paul Papin, 15 rue André Boquel-49055 Angers, France 3 Unité de Microbiologie Structurale, Institut Pasteur, CNRS, Univ. Paris, F-75015 Paris, France 4 Equipe ATIP AVENIR, CRCINA, INSERM, Univ. Nantes, Univ. Angers, 4 rue Larrey, F-49933 Angers, France * Correspondence: [email protected] (L.M.); [email protected] (P.B.) These three authors contribute equally to this work. y Received: 29 June 2019; Accepted: 3 September 2019; Published: 4 September 2019 Abstract: Pain currently represents the most common symptom for which medical attention is sought by patients. The available treatments have limited effectiveness and significant side-effects. In addition, most often, the duration of analgesia is short. Today, the handling of pain remains a major challenge. One promising alternative for the discovery of novel potent analgesics is to take inspiration from Mother Nature; in this context, the detailed investigation of the intriguing analgesia implemented in Buruli ulcer, an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium ulcerans and characterized by painless ulcerative lesions, seems particularly promising. More precisely, in this disease, the painless skin ulcers are caused by mycolactone, a polyketide lactone exotoxin. In fact, mycolactone exerts a wide range of effects on the host, besides being responsible for analgesia, as it has been shown notably to modulate the immune response or to provoke apoptosis. -

Ultrasound-Guided Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block (FICB)

Ultrasound-Guided Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block (FICB) Hip Fracture Any of the following present? 1) Neurologic deficit 2) Multisystem Trauma 3) Allergy to local anesthetic Yes *Anticoagulated patients – physician No discretion Standard Care Procedure Details 1) Document distal neurovascular exam in EPIC 1) PO acetaminophen 2) Consult ortho (do not need to await callback) (1,000mg) 3) Obtain verbal consent from patient 2) Consider 0.1 mg/kg 4) Position Patient and U/S Machine morphine or opioid 5) Order Bupivacaine (dose dependent) a. Max 2 mg/kg equivalent b. i.e. 100 mg safe for 50 kg patient 3) Screening labs, CXR, 6) Standard ASA monitoring (telemetry during procedure with ECG, type and screen continuous pulse oximetry, BP measurement, and IV access) 7) Perform FICB 4) Consult orthopedics and medicine as 8) Inform patients on block characteristics: a. Onset ~ 20 minutes necessary b. Duration ~ 8-12 hours Equipment Required Counseling Ultrasound Machine 1) Linear/Vascular Probe set to “Nerve” Benefits setting for best results Decreases: Anesthetic: 1) Pain 1) 0.5% Bupivacaine (20-30 cc) 2) 1% Lidocaine (3-5 cc) 2) Delirium 3) Opioids Saline (10 cc) 4) Hypoxia Syringes: 1) 30 cc 2) 3-5 cc Risks Needles: 1) Pain at injection site 1) Blunt fill 2) Temporary nerve palsy 2) 25G 3) 18G LP needle 3) Intravascular injection Chloroprep or Alcohol swab(s) 4) Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity * (LAST) * LAST (local anesthetic systemic toxicity) 1) Rare and only with intravascular injection which an ultrasound guided approach prevents. 2) Signs include arrhythmias, seizures, convulsions 3) Treatment a. -

Herestraat 49, B-3000 Leuven Yves Kremer, CU Saint-Luc, Av

Editor | Prof. Dr. V. Bonhomme CO-Editors | Dr. Y. Kremer — Prof. Dr. M. Van de Velde ACTA ANAESTHESIOLOGICA JOURNAL OF THE BELGIAN SOCIETY OF ANESTHESIOLOGY, RESUSCITATION, PERIOPERATIVE MEDICINE AND PAIN MANAGEMENT (BeSARPP) BELGICA Indexed in EMBASE l EXCERPTA MEDICA ISSN: 2736-5239 Suppl. 1 202071 Master Theses www.besarpp.be Cover-1 -71/suppl.indd 1 12/01/2021 12:37 ACTA ANÆSTHESIOLOGICA BELGICA 2020 – 71 – Supplement 1 EDITORS Editor-in-chief : Vincent Bonhomme, CHU Liège, av. de l’Hôpital 1, B-4000 Liège Co-Editors : Marc Van de Velde, KU Leuven, Herestraat 49, B-3000 Leuven Yves Kremer, CU Saint-Luc, av. Hippocrate, B-1200 Woluwe-Saint-Lambert Associate Editors : Margaretha Breebaart, UZA, Wilrijkstraat 10, B-2650 Edegem Christian Verborgh, UZ Brussel, Laarbeeklaan 101, B-1090 Jette Fernande Lois, CHU Liège, av. de l’Hôpital 1, B-4000 Liège Annelies Moerman, UZ Gent, C. Heymanslaan 10, B-9000 Gent Mona Monemi, CU Saint-Luc, av. Hippocrate, B-1200 Woluwe-Saint-Lambert Steffen Rex, KU Leuven, Herestraat 49, B-3000 Leuven Editorial assistant Carine Vauchel Dpt of Anesthesia & ICM, CHU Liège, B-4000 Liège Phone: 32-4 321 6470; Email: [email protected] Administration secretaries MediCongress Charlotte Schaek and Astrid Dedrie Noorwegenstraat 49, B-9940 Evergem Phone : +32 9 218 85 85 ; Email : [email protected] Subscription The annual subscription includes 4 issues and supplements (if any). 4 issues 1 issue (+supplements) Belgium 40€ 110€ Other Countries 50€ 150€ BeSARPP account number : BE97 0018 1614 5649 - Swift GEBABEBB Publicity : Luc Foubert, treasurer, OLV Ziekenhuis Aalst, Moorselbaan 164, B-9300 Aalst, phone: +32 53 72 44 61 ; Email : [email protected] Responsible Editor : Prof. -

Pharmacology – Inhalant Anesthetics

Pharmacology- Inhalant Anesthetics Lyon Lee DVM PhD DACVA Introduction • Maintenance of general anesthesia is primarily carried out using inhalation anesthetics, although intravenous anesthetics may be used for short procedures. • Inhalation anesthetics provide quicker changes of anesthetic depth than injectable anesthetics, and reversal of central nervous depression is more readily achieved, explaining for its popularity in prolonged anesthesia (less risk of overdosing, less accumulation and quicker recovery) (see table 1) Table 1. Comparison of inhalant and injectable anesthetics Inhalant Technique Injectable Technique Expensive Equipment Cheap (needles, syringes) Patent Airway and high O2 Not necessarily Better control of anesthetic depth Once given, suffer the consequences Ease of elimination (ventilation) Only through metabolism & Excretion Pollution No • Commonly administered inhalant anesthetics include volatile liquids such as isoflurane, halothane, sevoflurane and desflurane, and inorganic gas, nitrous oxide (N2O). Except N2O, these volatile anesthetics are chemically ‘halogenated hydrocarbons’ and all are closely related. • Physical characteristics of volatile anesthetics govern their clinical effects and practicality associated with their use. Table 2. Physical characteristics of some volatile anesthetic agents. (MAC is for man) Name partition coefficient. boiling point MAC % blood /gas oil/gas (deg=C) Nitrous oxide 0.47 1.4 -89 105 Cyclopropane 0.55 11.5 -34 9.2 Halothane 2.4 220 50.2 0.75 Methoxyflurane 11.0 950 104.7 0.2 Enflurane 1.9 98 56.5 1.68 Isoflurane 1.4 97 48.5 1.15 Sevoflurane 0.6 53 58.5 2.5 Desflurane 0.42 18.7 25 5.72 Diethyl ether 12 65 34.6 1.92 Chloroform 8 400 61.2 0.77 Trichloroethylene 9 714 86.7 0.23 • The volatile anesthetics are administered as vapors after their evaporization in devices known as vaporizers. -

Chewable Lozenge Formulation

Umashankar M S et al. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2016, 7 (4) INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF PHARMACY www.irjponline.com ISSN 2230 – 8407 Review Article CHEWABLE LOZENGE FORMULATION- A REVIEW Umashankar M S *, Dinesh S R, Rini R, Lakshmi K S, Damodharan N SRM College of Pharmacy, SRM University, Kattankulathur, India *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Article Received on: 11/02/16 Revised on: 13/03/16 Approved for publication: 28/03/16 DOI: 10.7897/2230-8407.07432 ABSTRACT Development of lozenges dated back to 20thcentury and is still remain popular among the consumer and hence it has continued commercial production. Lozenges are palatable solid unit dosage form administrated in the oral cavity. They meant to be dissolved in mouth or pharynx for its local or systemic effect. Lozenge tablets provide several advantages as pharmaceutical formulations however with some disadvantages. Lozenge as a dosage form can be adopted for drug delivery across buccal route, labial route, gingival route and sublingual route. Multiple drugs can also be incorporated in them for chronic illness treatments. Lozenge enables loading of wide range of active ingredients for oral systemic delivery of drugs. Lozenges are available as over the counter medications in the form of caramel based soft lozenges, hard candy lozenges and compressed tablet lozenges containing drugs for sore throat, mouth infection and as mouth fresheners. The rationale behind the use of medicated lozenges as one of the most favored dosage form for the delivery of antitussive drugs. This review focuses various aspects of lozenge formulation providing an insight to the formulation scientist on novel application of lozenge drug delivery system. -

Clinical Excellence Series Volume VI an Evidence-Based Approach to Infectious Disease

Clinical Excellence Series n Volume VI An Evidence-Based Approach To Infectious Disease Inside The Young Febrile Child: Evidence-Based Diagnostic And Therapeutic Strategies Pharyngitis In The ED: Diagnostic Challenges And Management Dilemmas HIV-Related Illnesses: The Challenge Of Emergency Department Management Antibiotics In The ED: How To Avoid The Common Mistake Of Treating Not Wisely, But Too Well Brought to you exclusively by the publisher of: An Evidence-Based Approach To Infectious Disease CEO: Robert Williford President & Publisher: Stephanie Ivy Associate Editor & CME Director: Jennifer Pai • Associate Editor: Dorothy Whisenhunt Director of Member Services: Liz Alvarez • Marketing & Customer Service Coordinator: Robin Williford Direct all questions to EB Medicine: 1-800-249-5770 • Fax: 1-770-500-1316 • Non-U.S. subscribers, call: 1-678-366-7933 EB Medicine • 5550 Triangle Pkwy Ste 150 • Norcross, GA 30092 E-mail: [email protected] • Web Site: www.ebmedicine.net The Emergency Medicine Practice Clinical Excellence Series, Volume Volume VI: An Evidence-Based Approach To Infectious Disease is published by EB Practice, LLC, d.b.a. EB Medicine, 5550 Triangle Pkwy Ste 150, Norcross, GA 30092. Opinions expressed are not necessarily those of this publication. Mention of products or services does not constitute endorsement. This publication is intended as a general guide and is intended to supplement, rather than substitute, professional judgment. It covers a highly technical and complex subject and should not be used for making specific medical decisions. The materials contained herein are not intended to establish policy, procedure, or standard of care. Emergency Medicine Practice, The Emergency Medicine Practice Clinical Excellence Series, and An Evidence-Based Approach To Infectious Disease are trademarks of EB Practice, LLC, d.b.a. -

Effects of Alfaxalone Or Propofol on Giant-Breed Dog Neonates Viability

animals Article Effects of Alfaxalone or Propofol on Giant-Breed Dog Neonates Viability During Elective Caesarean Sections Monica Melandri 1, Salvatore Alonge 1,* , Tanja Peric 2, Barbara Bolis 3 and Maria C Veronesi 3 1 Società Veterinaria “Il Melograno” Srl, 21018 Sesto Calende, Varese, Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of Agricultural, Food, Environmental and Animal Sciences, University of Udine, 33100 Udine, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Veterinary Medicine, Università degli Studi di Milano, 20100 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (B.B.); [email protected] (M.C.V.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-392-805-8524 Received: 20 September 2019; Accepted: 7 November 2019; Published: 13 November 2019 Simple Summary: Nowadays, thanks to the increased awareness of owners and breeders and to the most recent techniques available to veterinarians, the management of parturition, especially of C-sections, has become a topic of greater importance. Anesthesia is crucial and must be targeted to both the mother and neonates. The present study aimed to evaluate the effect of the induction agent alfaxalone on the vitality of puppies born from elective C-section, in comparison to propofol. After inducing general anesthesia for elective C-section, puppies from the mothers induced with alfaxalone had higher 5-min Apgar scores than those induced with propofol. The concentration of cortisol in fetal fluids collected at birth is neither influenced by the anesthetic protocol used, nor does it differ between amniotic and allantoic fluids. Nevertheless, the cortisol concentration in fetal fluids affects the relationship between anesthesia and the Apgar score: the present study highlights a significant relationship between the anesthetic protocol used and Apgar score in puppies, and fetal fluids cortisol concentration acts as a covariate of this relationship. -

Sore Throats

Pharyngitis Viruses cause most sore throats. When viruses infect your nose, $\/�P�1S1N(f F'ac+s: throat and sinuses, your body fightsback by making mucus. This helps Only about 15% of the people who wash out viruses. The mucus from your nose and sinuses drains into go to a doctor with a bad sore your throat. It can make your throat feel sore. Allergies, smoking, and throat have strep throat. You need air pollution can also lead to a sore throat. Some sore throats happen a test to tell for sure. You only need when stomach acid comes up into the throat. Yelling or speaking for a antibiotics if your test shows you long time can also make the throat sore. have strep throat. WJ.1affo l)O: Antibiotics don't work against viral infections. A sore throat • Drink more water. Honey and from a virus will get better on its own within a week or two. Antibiotics lemon in hot water or herbal teas won't make a sore throat go away any faster if it is caused by a virus. are good, too. Do not give honey Taking antibiotics when they are not needed may harm you by creating to children under 1. stronger germs. • Gargle with warm salt water. Talk with your health care provider about medicines that can help you • Suck on a hard candy, vitamin C feel better. For sore throats caused by allergies, your provider can help drop or throat lozenge. Do not give to young children. you figureout how to avoid the things that trigger your allergies. -

Submission Demonstrates That Flurbiprofen Lozenges Do Not Need to Be Restricted to Pharmacy Only Status Given;

Flurbiprofen reclassification to Unscheduled Medicine Reckitt Benckiser __________________________________________________________________________________________ Reclassification of a Medicine for consideration by the Medicine Classification Committee Application for the reclassification of flurbiprofen lozenges (8.75 mg flurbiprofen per lozenge) from Pharmacy Only Medicine to General Sale (Unscheduled) Medicine 30 June 2020 Submitted by: Reckitt Benckiser (New Zealand) Pty Limited Level 47 / 680 George Street Sydney NSW 2000, Australia 1 | Page Flurbiprofen reclassification to Unscheduled Medicine Reckitt Benckiser __________________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 4 Part A ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 1. International Non-proprietary Name of the medicine. ........................................................ 7 2. Proprietary name(s). ................................................................................................................ 7 3. Name and contact details of the company / organisation / individual requesting a reclassification. ............................................................................................................................. 7 4. Dose form(s) and strength(s) for which a change is -

Fascia Iliaca Block in the Emergency Department

The Royal College of Emergency Medicine Best Practice Guideline Fascia Iliaca Block in the Emergency Department 1 Revised: July 2020 Contents Summary of recommendations ...................................................................................................... 3 Scope ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Reason for development ................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Considerations ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Safety of FIB ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Improving safety of FIB .................................................................................................................. 5 Controversies regarding FIB ......................................................................................................... 5 Efficacy of FIB ................................................................................................................................... 6 Procedures within ED ....................................................................................................................