Hydro Politics in the Eastern Mediterranean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deficient Developmental Planning Leading to Water Conflicts Across Political Borders: the Way Forward

Engineering, 2021, 13, 158-172 https://www.scirp.org/journal/eng ISSN Online: 1947-394X ISSN Print: 1947-3931 Deficient Developmental Planning Leading to Water Conflicts across Political Borders: The Way Forward Elias Salameh1, Nadhir Al-Ansari2* 1University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan 2Lulea University of Technology, Lulea, Sweden How to cite this paper: Salameh, E. and Abstract Al-Ansari, N. (2021) Deficient Developmental Planning Leading to Water Conflicts across In this article, Turkey, Iran and Syria in the Middle East area are taken as Political Borders: The Way Forward. Engi- examples for deficient planning and development of water resources shared neering, 13, 158-172. with their downstream countries resulting in severe social, economic and polit- https://doi.org/10.4236/eng.2021.133012 ical percussions to these neighbors. The current situation in the Middle East Received: February 24, 2021 with wars against terrorism, uprising of population groups, and COVID-19 Accepted: March 22, 2021 Pandemic have not allowed the affected countries Jordan, Iraq and Syria to Published: March 25, 2021 properly react to the assaults of upstream water development and diversions Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and on their fair shares in the transboundary waters. The rivers’ upstream deve- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. lopmental schemes have not taken advantages of recent advanced technolo- This work is licensed under the Creative gical knowhow of water efficient development and use, seemingly because the Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). arising water problems and catastrophes will not affect these upstream coun- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ tries, but their downstream neighbors. -

Shared Waters – Shared Opportunities World Water Day March 22 Transboundary Waters in the ESCWA Region

Distr. LIMITED E/ESCWA/SDPD/2009/Technical material.1 2 March 2009 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR WESTERN ASIA (ESCWA) Shared Waters – Shared Opportunities World Water Day March 22 Transboundary Waters in the ESCWA Region UNITED NATIONS ESCWA The designations employed and the presentation of material on the maps contained herein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. 09-0104 Abbreviations Used In Map Credits CNRSL Lebanese National Council for Scientific Research GORS General Organization of Remote Sensing BGR Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources Introduction Shared water is a vital resource for many people around the world. In the ESCWA region, major shared rivers include the Nile, Tigris, Euphrates and Jordan. Many less well-known underground water reservoirs are also shared. Opportunities for negotiation and mutually beneficial use of water also exist in riparian countries, many based on principles of international law and resolutions on shared water. This fact sheet opens with an outline of the general principles of international water law and the major international conventions on shared water, before delineating the major transboundary river basins and shared water aquifers in the ESCWA region. In highlighting some of the most important transboundary water bodies in the region, it is hoped that increased focus and renewed effort will be exerted in creating cooperative agreements for better management of our most precious resource – water. -

The Blue Peace – Rethinking Middle East Water

With support from Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sweden Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, Switzerland Political Affairs Div IV of the Federal Dept of Foreign Affairs, Switzerland C-306, Montana, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri West, Mumbai 400 053, India Email: [email protected] Author : Sundeep Waslekar Project Director : Ilmas Futehally Project Coordinator and Principal Researcher : Ambika Vishwanath Research Analyst : Gitanjali Bakshi Creative Head : Preeti Rathi Motwani Research Advice and Review Group: Dr. Aysegul Kibaroglu (Turkey) Dr. Faisal Rifai (Syria) Dr. Marwan Haddad (Palestine Territories) Dr. Mohamed Saidam (Jordan) Prof. Muqdad Ali Al-Jabbari (Iraq) Dr. Selim Catafago (Lebanon) Eng. Shimon Tal (Israel) Project Advisory Group: Dr. Francois Muenger (Switzerland) Amb. Jean-Daniel Ruch (Switzerland) Mr. Dag Juhlin-Danfeld (Sweden) SFG expresses its gratitude to the Government of Sweden, Government of Switzerland, their agencies and departments, other supporters of the project, and members of the Research Advice and Review Group, for their cooperation in various forms. However, the analysis and views expressed in this report are of the Strategic Foresight Group only and do not in any way, direct or indirect, reflect any agreement, endorsement, or approval by any of the supporting organisations or their officials or by the experts associated with the review process or any other institutions or individuals. Copyright © Strategic Foresight Group 2011 ISBN 978-81-88262-14-4 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

The Hydropolitical Baseline of the Upper Jordan River

"# ! #$"%!&# '& %!!&! !"#$ %& ' ( ) *$ +,-*.+ / %&0 ! "# " ! "# "" $%%&!' "# "( %! ") "* !"+ "# ! ", ( %%&! "- (" %&!"- (( . -

Cooperation Among Adversaries. Regionalism in the Middle East

Cooperation among adversaries. Regionalism in the Middle East. Master (M.A) in Advanced European and International Studies Trilingual Branch. Academic year 2009/10 Author: Supervisors: Katarzyna Krókowska Dagmar Röttsches – Dubois Matthias Wächter 1 Cooperation among adversaries. Regionalism in the Middle East. Katarzyna Krókowska Master (M.A) in Advanced European and International Studies Centre International de Formation Européenne Institut Européen des Hautes Études Internationales Trilingual Branch. Academic year 2009/10 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 Structure of the thesis ........................................................................................................... 7 Understanding and explaining regional cooperation .................................................. 8 Chapter 1: International Relations theory: approaches to understanding regional cooperation .................................................................................................. 11 Realism ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Transactionalism ........................................................................................................................................ 15 Game Theory ................................................................................................................................................ -

1.1 Overview of Shared Surface Water Resources in Western Asia

Overview of Shared Surface Water Resources in Western Asia Building Capacity for Accessing Disruptive Technologies for Improved Water Resources Management under Climate Change, Beirut, 14-15 January 2020 Joelle Comair Programme Associate Water Resources Section SDPD, ESCWA Inventory of Shared Water Resources in Western Asia The Inventory is: the first UN-led effort to take stock Objectives: of the region’s shared surface and • Identify, and document the state of shared water groundwater resources in a resources and their use comprehensive, systematic and standardized manner. • Improve the knowledge base and facilitate information access • Create awareness and stimulate informed dialogue within and between riparian countries Key Themes: • Support regional processes towards improved dialogue • hydrology, hydrogeology and cooperation over shared water resources • water resources development and use, • agreements and cross-border Launched in management efforts. September 2013 www.waterinventory.org [email protected] Euphrates River – Syrian Arab Republic Work Process & Methodology Overview Compilation of information • Pre-screening and compilation of the existing literature: ESCWA reports, regional literature, scientific publications, country papers, media reports, national statistics, national and regional maps, satellite imagery, etc to document and provide a comprehensive, descriptive analysis • Consultation with regional and international experts and involvement of ESCWA member countries through focal points for reviews and requests -

The Impact of Power on Water Rights: a Study of the Jordan and Tigris-Euphrates Basins

The Impact of Power on Water Rights: A Study of the Jordan and Tigris-Euphrates Basins by Jessica Berardinucci SIS Honors Capstone Supervised by Professors Linda Lucia Lubrano and Anthony Quainton AY 2009-2010 Submitted to the School of International Service American University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with University Honors in International Studies Bachelor of Arts Degree April 2010 Berardinucci 2 Abstract In water-scarce riparian regions, states utilize geographic and structural power to maximize their access to water. In the Jordan River Basin, which includes Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, and the Palestinian territories, and the Tigris-Euphrates River Basin, which includes Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, certain states cannot access enough water to have their human right to water fulfilled. This Capstone seeks to ascertain how state power can affect the fulfillment of water rights by conducting a dual case state of the Jordan and Tigris- Euphrates Basins. This dual case study is rooted in the realist tradition of international relations literature and contemporary water rights research. The data explores the actors’ historical use of economic, political, and military “instruments of power” in attempts to maximize their access to water. This paper determines that the riparian state with the greatest ability to utilize “instruments of power” is able to control water allocation, and thus determines the fulfillment of water rights throughout the basin. Berardinucci 3 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 1 Literature Review 4 Research Design 14 CASE STUDY: THE JORDAN RIVER BASIN 19 Analysis: The Use of Power 31 The Impact of Power on the Current Human Rights Situation 35 CASE STUDY: THE TIGRIS AND EUPHRATES BASIN 40 Analysis: The Use of Power 47 The Impact of Power on the Current Human Rights Situation 51 CONCLUSION 58 APPENDIX 61 BIBLIOGRAPHY Berardinucci 4 Research Agenda This Capstone researches the impact that power relations between riparian states have on the human right to water in the Middle East. -

Mapping Peace Between Syria and Israel

UNiteD StateS iNStitUte of peaCe www.usip.org SpeCial REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Frederic C. Hof Commissioned in mid-2008 by the United States Institute of Peace’s Center for Mediation and Conflict Resolution, this report builds upon two previous groundbreaking works by the author that deal with the obstacles to Syrian- Israeli peace and propose potential ways around them: a 1999 Middle East Insight monograph that defined the Mapping peace between phrase “line of June 4, 1967” in its Israeli-Syrian context, and a 2002 Israel-Syria “Treaty of Peace” drafted for the International Crisis Group. Both works are published Syria and israel online at www.usip.org as companion pieces to this report and expand upon a concept first broached by the author in his 1999 monograph: a Jordan Valley–Golan Heights Environmental Preserve under Syrian sovereignty that Summary would protect key water resources and facilitate Syrian- • Syrian-Israeli “proximity” peace talks orchestrated by Turkey in 2008 revived a Israeli people-to-people contacts. long-dormant track of the Arab-Israeli peace process. Although the talks were sus- Frederic C. Hof is the CEO of AALC, Ltd., an Arlington, pended because of Israeli military operations in the Gaza Strip, Israeli-Syrian peace Virginia, international business consulting firm. He directed might well facilitate a Palestinian state at peace with Israel. the field operations of the Sharm El-Sheikh (Mitchell) Fact- Finding Committee in 2001. • Syria’s “bottom line” for peace with Israel is the return of all the land seized from it by Israel in June 1967. -

INTERNATIONAL WATERS of the MIDDLE EAST from EUPHRATES-TIGRIS to NILE

'p MIN INTERNATIONAL WATERS of the MIDDLE EAST FROM EUPHRATES-TIGRIS TO NILE WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT SERIES WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT SERtES 2 International Waters of the Middle East From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile Water Resources Management Series I. Water for Sustainable Development in the Twenty-first Century edited by ASIT K. BIswAs, MOHAMMED JELLALI AND GLENN STOUT International Waters of the Middle East: From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile edited by ASIT K. BlswAs Management and Development of Major Rivers edited by ALY M. SHADY, MOHAMED EL-MOTTASSEM, ESSAM ALY ABDEL-HAFIZ AND AsIT K. BIswAs WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT SERIES : 2 International Waters of the Middle East From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile Edited b' ASIT K. BISWAS Sponsored by United Nations University International Water Resources Association With the support of Sasakawa Peace Foundation United Nations Entne4rogramme' '4RY 1' Am ir THE SASAKAWA PEACE FOUNDATION OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS BOMBAY DELHi CALCUTTA MADRAS 1994 Oxford University Press, Walton Street, Oxford 0X2 6DP Oxford New York Toronto Delhi Bombay Calcutta Madras Karachi KualaLumpur Singapore Hong Kong Tokyo Nairobi Dar esSalaam Cape Town Melbourne Auckland Madrid anji.ssocia:es in Berlin Ibadan First published 1994 © United Nations University, International Water Resources Association, Sasakawa Peace Foundation and United Nations Environ,nent Programme, 1994 ISBN 0 19 563557 4 Printed in India Typeset by Alliance Phototypesetters, Pondicherry 605 013 Printed at Rajkamal Electric Press, Delhi 110 033 Published by Neil O'Brien, Oxford University Press YMCA Library Building, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 110 001 This hook is dedicated to DR TAKASHI SHIRASU as a mark of esteem for his contributions to peace and a token of true regard for a friend Contents List of Contributors IX Series Preface xi Preface Xiii I. -

Religion in Language Policy, and the Survival of Syriac

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2008 Religion in language policy, and the survival of Syriac Ibrahim George Aboud Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Aboud, Ibrahim George, "Religion in language policy, and the survival of Syriac" (2008). Theses Digitization Project. 3426. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3426 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELIGION IN LANGUAGE POLICY, AND THE SURVIVAL OF SYRIAC A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition: Teaching English as a Second Language by Ibrahim George Aboud March 2008 RELIGION IN LANGUAGE POLICY, AND THE SURVIVAL OF SYRIAC A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Ibrahim George Aboud March 2008 Approved by: 3/llW Salaam Yousif, Date Ronq Chen ABSTRACT Religious systems exert tremendous influence on shaping language policy, both in the ancient and the modern states of the Fertile Crescent. For two millennia the Syriac language was a symbol of identity among its Christian communities. Religious disputes in the Byzantine era produced not only doctrinal rivalries but also linguistic differences. Throughout the Islamic era, the Syriac language remained the language of the majority despite.Arabic hegemony. -

Impact of the Syrian Refugee Crisis on Land Use and Transboundary Freshwater Resources

Impact of the Syrian refugee crisis on land use and transboundary freshwater resources Marc François Müllera,b,1, Jim Yoona, Steven M. Gorelicka, Nicolas Avissec, and Amaury Tilmantc aDepartment of Earth System Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305; bDepartment of Civil & Environmental Engineering & Earth Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556; and cDepartment of Civil and Water Engineering, Université Laval, Quebec, QC, Canada G1V 0A6 Edited by Peter H. Gleick, Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environment, and Security, Oakland, CA, and approved November 1, 2016 (received for review August 27, 2016) Since 2013, hundreds of thousands of refugees have migrated operational in 2007. The reservoir captures much of the Yarmouk southward to Jordan to escape the Syrian civil war that began in flow, serving as a significant water storage facility for Jordan. In the mid-2011. Evaluating impacts of conflict and migration on land use past several decades, the Yarmouk watershed upstream of the Al- and transboundary water resources in an active war zone remains Wehda dam has been extensively exploited by Syria with the con- a challenge. However, spatial and statistical analyses of satellite struction of 21 dams to enable intensive agricultural irrigation, imagery for the recent period of Syrian refugee mass migration resulting in substantial flow decreases to downstream Jordan and provide evidence of rapid changes in land use, water use, and water Israel (Fig. S1D). After 2012, inflow records at Al-Wehda reservoir management in the Yarmouk–Jordan river watershed shared by Syria, show a sudden reversal in this declining flow trend, an unexpected Jordan, and Israel. -

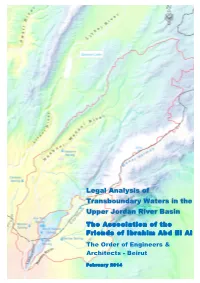

Legal Analysis of Transboundary Waters in the Upper Jordan River Basin

Legal Analysis of Transboundary Waters in the Upper Jordan River Basin The Association of the Friends of Ibrahim Abd El Al The Order of Engineers & Architects - Beirut February 2014 THE ASSOCIATION OF THE FRIENDS OF IBRAHIM ABD EL AL ( AFIAL) SPONSORED BY: THE ORDER OF ENGINEERS AND ARCHITECTS - BEIRUT Written by HE. Ziyad Baroud, Esq. Attorney at law, Managing Partner HBD-T Law firm, Lecturer at USJ, Former Lebanese Minister of Interior and Municipalities Me. Ghadir El-Alayli, Esq. Attorney at law, Senior Associate HBD-T, PhD student Chadi Abdallah, PhD Geosiences, Remote Sensing & GIS MarK Zeitoun, PhD Coordinator Reviewed Antoine Salameh, Eng. President, Scientific Committee of AFIAL by Prof Stephen McCaffrey McGeorge School of Law, University of the Pacific Michael Talhami, Eng. Independent researcher TO CITE THIS STUDY AFIAL, 2014. Legal Analysis of Transboundary Waters in the Upper Jordan River Basin. Beirut, Association of the Friends of Ibrahim Abd El Al. 91pp + Annexes NOTES This study was undertaken by a team assembled by the Association of the Friends of Ibrahim Abd el Al, with the generous support of the Order of Engineers and Architects of Lebanon. Any questions or comments about the study should be directed to AFIAL. AFIAL would like to emphasize that the analysis and recommendations are suggested without any prejudice to the state of relations between the Government of Lebanon and the Occupying State of Israel, and the non-recognition of the latter by the Government of Lebanon. Copyright © 2014, Association of the Friends of Ibrahim Abd el Al. Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS III FIGURES VII TABLES IX ACRONYMS X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XI SECTION 1 – INTRODUCTION 1 1.