Chlorhexidine Or Povidone-Iodine Do We Follow the Guidelines Or the Package Insert?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chlorhexidine Soap Instructions

Pre-Operative Bathing Instructions Infection Prevention Because skin is not sterile, we need to be sure that your skin is as free of germs as possible before your admission. You can reduce the number of germs on your skin and decrease the risk of surgical site infection by preparing your skin with a special soap called chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG). The instructions for use are attached. What is CHG? CHG is a chemical antiseptic that is effective on both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It is both bacteriocidal (kills) and bacteriostatic (stops reproductions) of any bacteria on the skin. CHG is in several products such as mouthwash, contact lens solution, wound wash, acne skin wash topical skin cleansers (chloraprep-what is used to clean your skin before an IV), thus we do not expect using this soap will cause skin irritation but please speak with your primary care physician to discuss any allergies. Studies show that repeated use of CHG soap enhances the ability of CHG to reduce bacterial counts on the skin; not only during the immediate period after the shower, but for a number of hours afterward. Studies suggest that patients may benefit from bathing or showering with CHG soap for at least 3 days before surgery in order to achieve the most benefit. It is unknown whether using CHG soap for less than or more than 3 days is beneficial. We recommend 3 days of treatment but understand this is not always possible and bathing the night before and the day of using CHG is acceptable. CHG soap can be purchased at any local pharmacy. -

Health Evidence Review Commission's Value-Based Benefits Subcommittee

Health Evidence Review Commission's Value-based Benefits Subcommittee September 28, 2017 8:00 AM - 1:00 PM Clackamas Community College Wilsonville Training Center, Room 111-112 29373 SW Town Center Loop E, Wilsonville, Oregon, 97070 Section 1.0 Call to Order AGENDA VALUE-BASED BENEFITS SUBCOMMITTEE September 28, 2017 8:00am - 1:00pm Wilsonville Training Center, Rooms 111-112 29353 SW Town Center Loop E Wilsonville, Oregon 97070 A working lunch will be served at approximately 12:00 PM All times are approximate I. Call to Order, Roll Call, Approval of Minutes – Kevin Olson 8:00 AM II. Staff report – Ariel Smits, Cat Livingston, Darren Coffman 8:05 AM A. Chronic Pain Task Force meeting report B. Errata C. Retreat III. Straightforward/Consent agenda – Ariel Smits 8:15 AM A. Consent table B. Straightforward Modifications to the Prioritized List Changes: Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Mellitus C. Straightforward changes to the PPI guideline for Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia D. Tobacco cessation guideline clarification IV. Advisory Panel reports 8:25 AM A. OHAP 1. 2018 CDT code placement recommendations V. Previous discussion items 8:30 AM A. Consideration for prioritization on lines 500/660, Services with Minimal or No Clinical Benefit and/or Low Cost-Effectiveness 1. New medications for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy i. deflazacort (Emflaza) ii. etepliren (Exondys 51) VI. New discussion items 9:30 AM A. Testicular prostheses B. Capsulorrhaphy for recurrent shoulder dislocation C. Transcutaneous neurostimulators D. Physical therapy for interstitial cystitis E. Acute peripheral nerve injuries F. SOI on role of Prioritized List in Coverage G. -

Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis CASE REPORT

Richa et al.: Management of Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis CASE REPORT Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis and its management: A Rare Case of Homozygous Twins Richa1, Neeraj Kumar2, Krishan Gauba3, Debojyoti Chatterjee4 1-Tutor, Unit of Pedodontics and preventive dentistry, ESIC Dental College and Hospital, Rohini, Delhi. 2-Senior Resident, Unit of Pedodontics and preventive dentistry, Oral Health Sciences Centre, Post Correspondence to: Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research , Chandigarh, India. 3-Professor and Head, Dr. Richa, Tutor, Unit of Pedodontics and Department of Oral Health Sciences Centre, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and preventive dentistry, ESIC Dental College and Research, Chandigarh, India. 4-Senior Resident, Department of Histopathology, Oral Health Sciences Hospital, Rohini, Delhi Centre, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. Contact Us: www.ijohmr.com ABSTRACT Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF) is a rare condition which manifests itself by gingival overgrowth covering teeth to variable degree i.e. either isolated or as part of a syndrome. This paper presented two cases of generalized and severe HGF in siblings without any systemic illness. HGF was confirmed based on family history, clinical and histological examination. Management of both the cases was done conservatively. Quadrant wise gingivectomy using ledge and wedge method was adopted and followed for 12 months. The surgical procedure yielded functionally and esthetically satisfying results with no recurrence. KEYWORDS: Gingival enlargement, Hereditary, homozygous, Gingivectomy AA swollen gums. The patient gave a history of swelling of upper gums that started 2 years back which gradually aaaasasasss INTRODUCTION increased in size. The child’s mother denied prenatal Hereditary Gingival Enlargement, being a rare entity, is exposure to tobacco, alcohol, and drug. -

Being Aware of Chlorhexidine Allergy

Being aware of chlorhexidine allergy If you have an immediate allergic reaction to chlorhexidine you may experience symptoms such as: x itching x skin rash (hives) x swelling x anaphylaxis. People who develop anaphylaxis to chlorhexidine may have experienced mild reactions, such as skin rash, to chlorhexidine before. Irritant contact dermatitis or allergic contact dermatitis Chlorhexidine can also cause irritant dermatitis. This is not a true allergic reaction. It is caused by chlorhexidine directly irritating skin and results in rough, dry and scaly Chlorhexidine is an antiseptic. Allergic reactions to skin, sometimes with weeping sores. chlorhexidine are rare but are becoming more common. Chlorhexidine is used in many products both in Chlorhexidine can also cause allergic contact hospitals and in the community. dermatitis. Symptoms look like irritant dermatitis, but the cause of the symptoms is delayed by 12-48 hours Why have I been given this factsheet? after contact with chlorhexidine. You have been given this brochure because you have had a reaction to a medication, a medical dressing Both irritant dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis or antiseptic. This may or may not be caused by a caused by chlorhexidine are annoying but not chlorhexidine allergy. dangerous. It is important that you are aware of the possibility of an It is recommended that you avoid chlorhexidine if you allergy. experience these responses as some people have gone on to develop immediate allergic reaction to chlorhexidine. Allergic reactions to chlorhexidine Severe allergic reactions to chlorhexidine are rare, but How do I know which products contain they can be serious. Immediate allergic reactions can chlorhexidine? cause anaphlaxis (a very severe allergic reaction which can be life-threatening). -

3Rd Quarter 2001 Bulletin

In This Issue... Promoting Colorectal Cancer Screening Important Information and Documentaion on Promoting the Prevention of Colorectal Cancer ....................................................................................................... 9 Intestinal and Multi-Visceral Transplantation Coverage Guidelines and Requirements for Approval of Transplantation Facilities12 Expanded Coverage of Positron Emission Tomography Scans New HCPCS Codes and Coverage Guidelines Effective July 1, 2001 ..................... 14 Skilled Nursing Facility Consolidated Billing Clarification on HCPCS Coding Update and Part B Fee Schedule Services .......... 22 Final Medical Review Policies 29540, 33282, 67221, 70450, 76090, 76092, 82947, 86353, 93922, C1300, C1305, J0207, and J9293 ......................................................................................... 31 Outpatient Prospective Payment System Bulletin Devices Eligible for Transitional Pass-Through Payments, New Categories and Crosswalk C-codes to Be Used in Coding Devices Eligible for Transitional Pass-Through Payments ............................................................................................ 68 Features From the Medical Director 3 he Medicare A Bulletin Administrative 4 Tshould be shared with all General Information 5 health care practitioners and managerial members of the General Coverage 12 provider/supplier staff. Hospital Services 17 Publications issued after End Stage Renal Disease 19 October 1, 1997, are available at no-cost from our provider Skilled Nursing Facility -

Efficacy of Chlorhexidine, Hydrogen Peroxide and Tulsi Extract Mouthwash in Reducing Halitosis Using Spectrophotometric Analysis: a Randomized Controlled Trial

J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;11(5):e457-63. Tulsi mouthwash efficacy in reducing halitosis using spectrophotometric analysis Journal section: Community and Preventive Dentistry doi:10.4317/jced.55523 Publication Types: Research http://dx.doi.org/10.4317/jced.55523 Efficacy of chlorhexidine, hydrogen peroxide and tulsi extract mouthwash in reducing halitosis using spectrophotometric analysis: A randomized controlled trial Kriti Sharma, Shashidhar Acharya, Eshan Verma, Deepak Singhal, Nishu Singla 1 Dept. of Public Health Dentistry, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher education, Madhav Nagar, Manipal, Karnataka Correspondence: Dept. of Public Health Dentistry Manipal College of Dental Sciences Manipal Academy of Higher education Madhav Nagar Sharma K, Acharya S, Verma E, Singhal D, Singla N. Efficacy of chlorhexi- Manipal, Karnataka – 576104 dine, hydrogen peroxide and tulsi extract mouthwash in reducing halitosis [email protected] using spectrophotometric analysis: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;11(5):e457-63. http://www.medicinaoral.com/odo/volumenes/v11i5/jcedv11i5p457.pdf Received: 21/12/2018 Accepted: 13/04/2019 Article Number: 55523 http://www.medicinaoral.com/odo/indice.htm © Medicina Oral S. L. C.I.F. B 96689336 - eISSN: 1989-5488 eMail: [email protected] Indexed in: Pubmed Pubmed Central® (PMC) Scopus DOI® System Abstract Background: To evaluate the efficacy of tulsi extract mouthrinse in reducing halitosis as compared to chlorhexidine and hydrogen peroxide mouthrinses using spectrophotometric analysis. Material and Methods: It was a parallel, single center, double blinded randomized controlled trial of 15 days du- ration. A total of 300 participants were screened, out of which 45 subjects those fulfilled inclusion criteria of age range 17-35 years were included in the trial. -

Chlorhexidine Gluconate Versus Hydrogen Peroxide Oral Hygiene

TITLE: Chlorhexidine Gluconate versus Hydrogen Peroxide Oral Hygiene Rinse Preparations for the Prevention of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: Comparative Clinical Effectiveness and Safety DATE: 25 April 2012 RESEARCH QUESTIONS 1. What is the comparative clinical effectiveness of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate oral rinse solutions versus hydrogen peroxide oral rinse solutions for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia? 2. What is the clinical evidence regarding the safety of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate and hydrogen peroxide oral rinse solutions for ventilated patients? KEY MESSAGE No evidence was identified regarding the comparative clinical effectiveness or safety of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate oral rinse solutions versus hydrogen peroxide oral rinse solutions for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. METHODS A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including PubMed, The Cochrane Library (2012, Issue 3), University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and abbreviated lists of major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. No filters were applied to limit the retrieval by study type. The search was also limited to English language documents published between Jan 1, 2007 and Apr 11, 2012. Internet links were provided, where available. RESULTS No health technology assessments, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, randomized- controlled trials, or non-randomized studies were identified regarding the comparative clinical Disclaimer: The Rapid Response Service is an information service for those involved in planning and providing health care in Canada. Rapid responses are based on a limited literature search and are not comprehensive, systematic reviews. The intent is to provide a list of sources of the best evidence on the topic that CADTH could identify using all reasonable efforts within the time allowed. -

Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis, Inherited Disease, Gingivectomy

Clinical Practice 2014, 3(1): 7-10 DOI: 10.5923/j.cp.20140301.03 Hereditary Gingival Fibromatosis - A Case Report Anand Kishore1,*, Vivek Srivastava2, Ajeeta Meenawat2, Ambrish Kaushal3 1King George Medical College, Lucknow 2BBD College of dental sciences 3Chandra Dental College & Hospital Abstract Hereditary gingival fibromatosis is characterized by a slow benign enlargement of gingival tissue. It causes teeth being partially or totally covered by enlarged gingiva, causing esthetic and functional problems. It is usually transmitted both as autosomal dominant trait and autosomal recessive inheritance although sporadic cases are commonly reported. This paper reports three cases of gingival fibromatosis out of which one was in a 15 year old girl treated with convectional gingivectomy. Keywords Hereditary gingival fibromatosis, Inherited disease, Gingivectomy having the gingival enlargement before the patient’s birth 1. Introduction and she got operated in the village government hospital. No further relevant medical history was present. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF) or Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis is a rare, benign, asymptomatic, non-hemorrhagic and non-exudative proliferative fibrous lesion of gingival tissue occurring equally among men and women, in both arches with varying intensity in individuals within the same family [1]. It occurs as an autosomal dominant condition although recessive form also does occur. Consanguinity seems to increase the risk of autosomal dominant inheritance. It affects the marginal gingival, attached gingival and interdental papilla presenting as pink, non-hemorrhagic and have a firm, fibrotic consistency [2]. It also shows a generalized firm nodular enlargement with smooth to stippled surfaces and minimal tendency to bleed. Figure 1. Gingival enlargement However, in some cases the enlargement can be so firm and dense that it feels like bone on palpation [3]. -

The Role of 0.12% Chlorhexidine Gluconate Oral Rinse (CHG) in the Ventilated Patient

What the experts say The role of 0.12% Chlorhexidine Gluconate Oral Rinse (CHG) in the ventilated patient Leading healthcare institutions and organizations have adopted protocols for oral care as part of their bundle of strategies used to address hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). These oral care protocols follow a comprehensive approach aimed at key reservoirs for bacteria on the teeth as well as within the oral cavity and oropharynx. One common and consistent element of these care bundles is the inclusion of 0.12% Chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) oral rinse. The following institutions recommend the use of 0.12% CHG as part of a comprehensive oral care protocol to address key risk factors that are known to lead to HAP and VAP. Recommendations & guidelines Institute for Healthcare Improvement Association for Professionals in Infection (IHI) 20121 Control and Epidemiology (APIC) 20094 • “A 2007 British Medical Journal study concluded • “In a meta-analysis, the incidence of VAP was that oral decontamination of mechanically ventilated significantly reduced by oral antiseptics such as adults using chlorhexidine is associated with a lower chlorhexidine…” risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia.” • “Perform routine antiseptic mouth care” • “...it makes sense that good oral hygiene and the use of antiseptic oral decontamination reduces the bacteria on the oral mucosa and the potential for bacterial American Hospital Association (AHA), colonization in the upper respiratory tract.” Health Research and Educational -

Vr Meds Ex01 3B 0825S Coding Manual Supplement Page 1

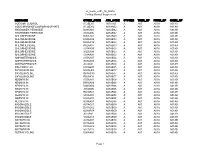

vr_meds_ex01_3b_0825s Coding Manual Supplement MEDNAME OTHER_CODE ATC_CODE SYSTEM THER_GP PHRM_GP CHEM_GP SODIUM FLUORIDE A12CD01 A01AA01 A A01 A01A A01AA SODIUM MONOFLUOROPHOSPHATE A12CD02 A01AA02 A A01 A01A A01AA HYDROGEN PEROXIDE D08AX01 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB HYDROGEN PEROXIDE S02AA06 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE B05CA02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D08AC02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D09AA12 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE R02AA05 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S01AX09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S02AA09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S03AA04 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B A07AA07 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B G01AA03 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B J02AA01 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB POLYNOXYLIN D01AE05 A01AB05 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE D08AH03 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE G01AC30 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE R02AA14 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN A07AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN B05CA09 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN D06AX04 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN J01GB05 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN R02AB01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S01AA03 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S02AA07 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S03AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE A07AC01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE D01AC02 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE G01AF04 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE J02AB01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE S02AA13 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB NATAMYCIN A07AA03 A01AB10 A A01 -

AHRQ Quality Indicators Fact Sheet

AHRQ Quality Indicators Toolkit Fact Sheet on Inpatient Quality Indicators What are the Inpatient Quality Indicators? The Inpatient Quality Indicators (IQIs) include 28 provider-level indicators established by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) that can be used with hospital inpatient discharge data to provide a perspective on quality. They are grouped into the following four sets: • Volume indicators are proxy, or indirect, measures of quality based on counts of admissions during which certain intensive, high-technology, or highly complex procedures were performed. They are based on evidence suggesting that hospitals performing more of these procedures may have better outcomes. • Mortality indicators for inpatient procedures include procedures for which mortality has been shown to vary across institutions and for which there is evidence that high mortality may be associated with poorer quality of care. • Mortality indicators for inpatient conditions include conditions for which mortality has been shown to vary substantially across institutions and for which evidence suggests that high mortality may be associated with deficiencies in the quality of care. • Utilization indicators examine procedures whose use varies significantly across hospitals and for which questions have been raised about overuse, underuse, or misuse. Mortality for Selected Procedures and Mortality for Selected Conditions are composite measures that AHRQ established in 2008. Each composite is estimated as a weighted average, across a set of IQIs, of the ratio of a hospital’s observed rate (OR) to its expected rate (ER), based on a reference population: OR/ER. The IQI-specific ratios are adjusted for reliability before they are averaged, to minimize the influence of ratios that are high or low at a specific hospital by chance. -

The Use and Efficacy of Professional Topical Fluorides a Peer-Reviewed Publication Written by N

Earn 2 CE credits This course was written for dentists, dental hygienists, and assistants. The Use and Efficacy of Professional Topical Fluorides A Peer-Reviewed Publication Written by N. Sue Seale, DDS, MSD and Diane M. Daubert, RDH, MS PennWell designates this activity for 2 Continuing Educational Credits Publication date: 9/2010 Go Green, Go Online to take your course Expiry date: 8/31/2013 This course has been made possible through an unrestricted educational grant. The cost of this CE course is $49.00 for 2 CE credits. Cancellation/Refund Policy: Any participant who is not 100% satisfied with this course can request a full refund by contacting PennWell in writing. Educational Objectives used to treat dentinal hypersensitivity, including fluoride varnish The overall goal of this article is to provide the reader with infor- and other in-office desensitizers as well as home-use products. mation on the use, efficacy and safety of professional topical fluo- rides. In addition, current recommendations based on caries risk Recognition of the role of fluoridated water in caries level are addressed. Upon completion of this course, the reader reduction led to the development of other modes will be able to do the following: of fluoride delivery. 1. List the types of professional topical fluorides that are avail- able in the US and Canada 2. List and describe the ADA recommendations on the use of Professional Topical Fluorides professional topical fluorides Professional topical fluorides include fluoride gels, foams, rinses 3. List and describe the evidence on efficacy and safety for and varnishes. Traditionally, professional fluoride treatment in the sodium fluoride varnishes US and Canada involved the use of fluoride gels in trays.