A Species-Focused Target for the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SDG Indicator Metadata (Harmonized Metadata Template - Format Version 1.0)

Last updated: 4 January 2021 SDG indicator metadata (Harmonized metadata template - format version 1.0) 0. Indicator information 0.a. Goal Goal 15: Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss 0.b. Target Target 15.5: Take urgent and significant action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats, halt the loss of biodiversity and, by 2020, protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species 0.c. Indicator Indicator 15.5.1: Red List Index 0.d. Series 0.e. Metadata update 4 January 2021 0.f. Related indicators Disaggregations of the Red List Index are also of particular relevance as indicators towards the following SDG targets (Brooks et al. 2015): SDG 2.4 Red List Index (species used for food and medicine); SDG 2.5 Red List Index (wild relatives and local breeds); SDG 12.2 Red List Index (impacts of utilisation) (Butchart 2008); SDG 12.4 Red List Index (impacts of pollution); SDG 13.1 Red List Index (impacts of climate change); SDG 14.1 Red List Index (impacts of pollution on marine species); SDG 14.2 Red List Index (marine species); SDG 14.3 Red List Index (reef-building coral species) (Carpenter et al. 2008); SDG 14.4 Red List Index (impacts of utilisation on marine species); SDG 15.1 Red List Index (terrestrial & freshwater species); SDG 15.2 Red List Index (forest-specialist species); SDG 15.4 Red List Index (mountain species); SDG 15.7 Red List Index (impacts of utilisation) (Butchart 2008); and SDG 15.8 Red List Index (impacts of invasive alien species) (Butchart 2008, McGeoch et al. -

Improvements to the Red List Index Stuart H

Improvements to the Red List Index Stuart H. M. Butchart1*, H. Resit Akc¸akaya2, Janice Chanson3, Jonathan E. M. Baillie4, Ben Collen4, Suhel Quader5,8, Will R. Turner6, Rajan Amin4, Simon N. Stuart3, Craig Hilton-Taylor7 1 BirdLife International, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2 Applied Biomathematics, Setauket, New York, United States of America, 3 Conservation International/Center for Applied Biodiversity Science-World Conservation Union (IUCN)/Species Survival Commission Biodiversity Assessment Unit, IUCN Species Programme, Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Washington, D. C., United States of America, 4 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London, United Kingdom, 5 Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 6 Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Washington, D. C., United States of America, 7 World Conservation Union (IUCN) Species Programme, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 8 Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Sandy, United Kingdom The Red List Index uses information from the IUCN Red List to track trends in the projected overall extinction risk of sets of species. It has been widely recognised as an important component of the suite of indicators needed to measure progress towards the international target of significantly reducing the rate of biodiversity loss by 2010. However, further application of the RLI (to non-avian taxa in particular) has revealed some shortcomings in the original formula and approach: It performs inappropriately when a value of zero is reached; RLI values are affected by the frequency of assessments; and newly evaluated species may introduce bias. Here we propose a revision to the formula, and recommend how it should be applied in order to overcome these shortcomings. -

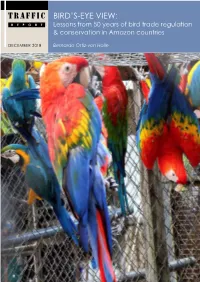

TRAFFIC Bird’S-Eye View: REPORT Lessons from 50 Years of Bird Trade Regulation & Conservation in Amazon Countries

TRAFFIC Bird’s-eye view: REPORT Lessons from 50 years of bird trade regulation & conservation in Amazon countries DECEMBER 2018 Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle About the author and this study: Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle, a biologist and TRAFFIC REPORT zoologist from the Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, has more than 30 years of experience in numerous aspects of conservation and its links to development. His decades of work for IUCN - International Union for Conservation of Nature and TRAFFIC TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring in South America have allowed him to network, is a leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade acquire a unique outlook on the mechanisms, in wild animals and plants in the context institutions, stakeholders and challenges facing of both biodiversity conservation and the conservation and sustainable use of species sustainable development. and ecosystems. Developing a critical perspective The views of the authors expressed in this of what works and what doesn’t to achieve lasting conservation goals, publication do not necessarily reflect those Bernardo has put this expertise within an historic framework to interpret of TRAFFIC, WWF, or IUCN. the outcomes of different wildlife policies and actions in South America, Reproduction of material appearing in offering guidance towards solutions that require new ways of looking at this report requires written permission wildlife trade-related problems. Always framing analysis and interpretation from the publisher. in the midst of the socioeconomic and political frameworks of each South The designations of geographical entities in American country and in the region as a whole, this work puts forward this publication, and the presentation of the conclusions and possible solutions to bird trade-related issues that are material, do not imply the expression of any linked to global dynamics, especially those related to wildlife trade. -

A Robust Goal Is Needed for Species in the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 16 April 2020 Title: A robust goal is needed for species in the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework Running title: A post-2020 goal for species conservation Authors: Brooke A. Williams*1,2, James E.M. Watson1,2,3, Stuart H.M. Butchart4,5, Michelle Ward1,2, Nathalie Butt2, Friederike C. Bolam6, Simon N. Stuart7, Thomas M. Brooks8,9,10, Louise Mair6, Philip J. K. McGowan6, Craig Hilton-Taylor11, David Mallon12, Ian Harrison8,13, Jeremy S. Simmonds1,2. Affiliations: 1School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia 2Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science, School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Queensland, Australia. 3Wildlife Conservation Society, Global Conservation Program, Bronx, NY 20460, USA. 4BirdLife International, The David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge CB2 3QZ, UK 5Department of Zoology, Cambridge University, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK 6School of Natural and Environmental Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU, UK 7Synchronicity Earth, 27-29 Cursitor Street, London, EC4A 1LT, UK 8IUCN, 28 rue Mauverney, CH-1196, Gland, Switzerland 9World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF), University of the Philippines Los Baños, Laguna, 4031, Philippines 10Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS 7001, Australia 11IUCN, The David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge CB2 3QZ, UK 12Division of Biology and Conservation Ecology, Manchester Metropolitan University, Chester St, Manchester, M1 5GD, U.K 13Conservation International, Arlington, VA 22202, USA Emails: Brooke A. Williams: [email protected]; James E.M. Watson: [email protected]; Stuart H.M. -

Assessing the Extinction Probability of the Purple-Winged Ground Dove, an Enigmatic Bamboo Specialist

fevo-09-624959 April 29, 2021 Time: 12:42 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 29 April 2021 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.624959 Assessing the Extinction Probability of the Purple-winged Ground Dove, an Enigmatic Bamboo Specialist Alexander C. Lees1,2*, Christian Devenish1, Juan Ignacio Areta3, Carlos Barros de Araújo4,5, Carlos Keller6, Ben Phalan7 and Luís Fábio Silveira8 1 Ecology and Environment Research Centre (EERC), Department of Natural Sciences, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, United Kingdom, 2 Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, United States, 3 Laboratorio de Ecología, Comportamiento y Sonidos Naturales, Instituto de Bio y Geociencias del Noroeste Argentino (IBIGEO-CONICET), Salta, Argentina, 4 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Monitoramento Ambiental, Centro de Ciências Aplicadas e Educação, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Rio Tinto, Brazil, 5 Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, Brazil, 6 Independent Researcher, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7 Centre for Conservation of Atlantic Forest Birds, Parque das Aves, Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil, 8 Seção de Aves, Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil The continued loss, fragmentation, and degradation of forest habitats are driving an Edited by: extinction crisis for tropical and subtropical bird species. This loss is particularly acute in Bruktawit Abdu Mahamued, the Atlantic Forest of South America, where it is unclear whether several endemic bird Kotebe Metropolitan University (KMU), Ethiopia species are extinct or extant. We collate and model spatiotemporal distributional data Reviewed by: for one such “lost” species, the Purple-winged Ground Dove Paraclaravis geoffroyi, John Woinarski, a Critically Endangered endemic of the Atlantic Forest biome, which is nomadic Charles Darwin University, Australia Sam Turvey, and apparently dependent on masting bamboo stands. -

A New Species of Cichlocolaptes Reichenbach 1853 (Furnariidae), the ‘Gritador-Do-Nordeste’, an Undescribed Trace of the Fading Bird Life of Northeastern Brazil

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 22(2), 75-94 ARTICLE June 2014 A new species of Cichlocolaptes Reichenbach 1853 (Furnariidae), the ‘gritador-do-nordeste’, an undescribed trace of the fading bird life of northeastern Brazil Juan Mazar Barnett1 and Dante Renato Corrêa Buzzetti2,3 1 Deceased. 2 Centro de Estudos Ornitológicos. Rua Álvaro Rodrigues 139, sala 4, CEP 04582-000, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 23 September 2013. Accepted on 21 May 2014. urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:5BE6C9E6-0E54-497E-84B8-90766A7A5A54, June 2014 ABSTRACT: A new species of treehunter, Cichlocolaptes mazarbarnetti sp. nov., is described from a specimen that for many years had been confused with Philydor novaesi. The morphology of this specimen, collected in 1986 at Pedra Branca, Murici, Alagoas, at 550 m elevation (currently the Murici Ecological Station), suggests its allocation in the genus Cichlocolaptes. The new species differs from P. novaesi by its considerably larger size, heavier body-mass, darker and more uniform forehead and crown, absence of buffy periocular- feathers, and a pale orange-rufous tail that contrasts with the rump and the rest of the dorsal plumage. It also has a flat-crowned appearance and a larger, deeper-based, and generally stouter bill. Behavioral specialization on bromeliads and vocal repertoire also suggest that the new species belongs in the genus Cichlocolaptes. The song of this species is markedly different from that of P. novaesi, and it closely matches that of Cichlocolaptes leucophrus. The new species is endemic to the ‘Pernambuco Center’ of endemism, where it inhabits dense, humid forests in hilly terrain. -

Lista Das Aves Do Brasil

90 Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee / Lista comentada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos content / conteÚDO Abstract ............................. 91 Charadriiformes ......................121 Scleruridae .............187 Charadriidae .........121 Dendrocolaptidae ...188 Introduction ........................ 92 Haematopodidae ...121 Xenopidae .............. 195 Methods ................................ 92 Recurvirostridae ....122 Furnariidae ............. 195 Burhinidae ............122 Tyrannides .......................203 Results ................................... 94 Chionidae .............122 Pipridae ..................203 Scolopacidae .........122 Oxyruncidae ..........206 Discussion ............................. 94 Thinocoridae .........124 Onychorhynchidae 206 Checklist of birds of Brazil 96 Jacanidae ...............124 Tityridae ................207 Rheiformes .............................. 96 Rostratulidae .........124 Cotingidae .............209 Tinamiformes .......................... 96 Glareolidae ............124 Pipritidae ............... 211 Anseriformes ........................... 98 Stercorariidae ........125 Platyrinchidae......... 211 Anhimidae ............ 98 Laridae ..................125 Tachurisidae ...........212 Anatidae ................ 98 Sternidae ...............126 Rhynchocyclidae ....212 Galliformes ..............................100 Rynchopidae .........127 Tyrannidae ............. 218 Cracidae ................100 Columbiformes -

1 Chapter 1.6. Evolution While You Are Watching Chapter 1.6

Chapter 1.6. Evolution While You Are Watching Chapter 1.6 describes more or less direct observations of evolution. Although Macroevolution which results in really profound changes of living beings occurs too slowly for such observations, substantial changes in a lineage can and do occur at the time scale of thousands or even hundreds of generations. Fast evolution is usually driven by strong selection and can involve numerous allele replacements. Direct observations of evolution come from data of four kinds. Section 1.6.1 treats observations of rapid evolution of nature. Here we will understand the concept of observation broadly, and include data on changes of phenotypes in continuous paleontological records and on local adaptation. However, under some circumstances evolution proceeds so rapidly that substantial changes occur in the course of decades, and, thus, can be literally observed. Section 1.6.2 considers domestication, a phenomenon which became common after the origin agriculture ~12,000 years ago, and evolution of domesticated plants and animals. Due to artificial selection and to natural selection under new environment, important phenotypes of many domesticated species are currently way outside the range of their natural variation, and the diversity of varieties is astonishing. Thus, domesticated species provide a rich source of data on evolution at a relatively small scale. Section 1.6.3 reviews data on experimental evolution in controlled populations of a variety of organisms. Such experiments are an important tool of evolutionary biology, which made it possible to directly observe a number of key phenomena. However, a limitation of evolutionary experiments is that they must deal with organisms with short generation times. -

Living in a Fragmented World: Birds in the Atlantic Forest Marco A

AmericanOrnithology.org Volume 122, 2020, pp. 1–14 DOI: 10.1093/condor/duaa023 SPECIAL FEATURE: Advances in Neotropical Ornithology Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/condor/article-abstract/doi/10.1093/condor/duaa023/5820423 by Universidade de Sao Paulo - USP user on 16 April 2020 Living in a fragmented world: Birds in the Atlantic Forest Marco A. Pizo,* and Vinicius R. Tonetti São Paulo State University (UNESP), Institute of Biosciences, Department of Biodiversity, Rio Claro, SP, Brazil *Corresponding author: [email protected] Submission Date: January 23, 2020; Editorial Acceptance Date: March 4, 2020; Published April 15, 2020 ABSTRACT The Atlantic Forest is the second largest tropical moist forest domain in South America after the Amazon, home to over 800 bird species (223 endemics or 27% of the avifauna). With only 28% of the original vegetation left, mostly fragmented and altered, the Atlantic Forest is a hotspot for bird conservation. We first introduce the extent, vegetation types, and exploitation history of the domain, and the composition and biogeographic affinities of its birds. We then provide an overview of the knowledge gathered so far on the ways Atlantic Forest birds thrive in the often-fragmented landscape, highlighting the landscape features that influence their occurrence and movement behavior. We end with the conser- vation issues affecting the Atlantic Forest birds and the actions hitherto taken to address them, including the establish- ment of conservation units, forest restoration, and rewilding. Keywords: Atlantic forest, bird ecology, conservation, restoration, rewilding Vivendo em um mundo fragmentado: as aves na Mata Atlântica RESUMO A Mata Atlântica (MA) é o segundo maior domínio formado principalmente por florestas tropicais úmidas da América do Sul depois da Amazônia, onde ocorrem mais de 800 espécies de aves (223 endêmicas ou 27% da avifauna). -

Global Conservation Translocation Perspectives: 2021. Case Studies from Around the Globe

Global conservation Global conservation translocation perspectives: 2021 translocation perspectives: 2021 IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group Global conservation translocation perspectives: 2021 Case studies from around the globe Edited by Pritpal S. Soorae IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group (CTSG) i The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or any of the funding organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. IUCN is pleased to acknowledge the support of its Framework Partners who provide core funding: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark; Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland; Government of France and the French Development Agency (AFD); the Ministry of Environment, Republic of Korea; the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad); the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the United States Department of State. Published by: IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group, Environment Agency - Abu Dhabi & Calgary Zoo, Canada. Copyright: © 2021 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Soorae, P. S. -

A Process for Assessing and Prioritzing Species Conservaton Needs: Going Beyond the Red List

A process for assessing and prioritzing species conservaton needs: going beyond the red list KEVIN JOHNSON, ANNE BAKER, KEVIN BULEY, LUIS CARRILLO, RICHARD GIBSON, GRAEME GILLESPIE, ROBERT C. LACY and KEVIN ZIPPEL SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL 1 Assessment Questions and Answer Scores. Assessment questions are designed to serve two purposes: to identify the needed conservation actions for each species and for quantitative prioritization of species for each action. Numeric scores from questions are used to develop the overall prioritization score, with the scores for the selected responses added to give a total. A higher total score represents a species of higher priority. Questions without scores are used as triggers for conservation actions, or to provide additional information to support subsequent action-planning, but are not used in the prioritization (scoring) process. Assessors select the most appropriate response to each question for the species being assessed. Section One – Review of external data 1. Extinction risk: What is the current IUCN Red List category for the taxon? The Red List category can be modified accordingly (for the purposes of this assessment only) if new/additional information is available, or if country-level Red List assessments exist. If the assessors consider that the Red List category of threat would change if the species was re- assessed using more current data than that which was used previously, or if a more recent national Red List assessment exists, a revised estimate of the new category can be chosen, and this will be used to calculate priorities and conservation actions. If a national Red List assessment exists, the national category of threat is used rather than the global category. -

Mexico's Ten Most Iconic Endangered Species

Alejandro Olivera Center for Biological Diversity, April 2018 Executive summary exico is one of the world’s most biologically rich nations, with diverse landscapes that are home to a treasure trove of wildlife, including plant and animal species found nowhere else. Sadly, in Mexico and Maround the world, species are becoming extinct because of human activities at rates never seen before. In this report we highlight the threats facing Mexico’s 10 most iconic endangered species to help illustrate the broader risks confronting the country’s imperiled plants and animals. These 10 species — which in most cases are protected only on paper — were chosen to reflect Mexico’s diversity of wildlife and ecosystems and the wide range of threats to the country’s biodiversity. New awareness of these unique animals and plants is critical to inspiring a nationwide demand to protect these critical components of Mexico’s natural heritage. Although the Mexican government began officially listing and protecting species as extinct, threatened, endangered, and “under special protection” in 1994 — more than 20 years ago — few species have actually recovered, and many critical threats continue unabated. In many cases, officials are failing to enforce crucial laws and regulations that would protect these species. Additionally, the Mexican government has not updated its official list of imperiled species, referred to as NOM059, since 2010, despite new and growing risks from climate change, habitat destruction, the wildlife trade and in some cases direct killing. This failure obscures the true plight of the nation’s endangered wildlife. The following 10 iconic endangered species are not adequately protected by the Mexican government: 1.