The One Water Roadmap: the Sustainable Management of Life's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wastewater Technology Fact Sheet: Ammonia Stripping

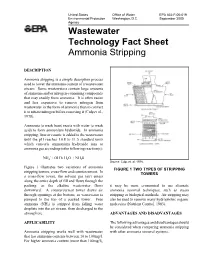

United States Office of Water EPA 832-F-00-019 Environmental Protection Washington, D.C. September 2000 Agency Wastewater Technology Fact Sheet Ammonia Stripping DESCRIPTION Ammonia stripping is a simple desorption process used to lower the ammonia content of a wastewater stream. Some wastewaters contain large amounts of ammonia and/or nitrogen-containing compounds that may readily form ammonia. It is often easier and less expensive to remove nitrogen from wastewater in the form of ammonia than to convert it to nitrate-nitrogen before removing it (Culp et al., 1978). Ammonia (a weak base) reacts with water (a weak acid) to form ammonium hydroxide. In ammonia stripping, lime or caustic is added to the wastewater until the pH reaches 10.8 to 11.5 standard units which converts ammonium hydroxide ions to ammonia gas according to the following reaction(s): + - NH4 + OH 6 H2O + NH38 Source: Culp, et. al, 1978. Figure 1 illustrates two variations of ammonia FIGURE 1 TWO TYPES OF STRIPPING stripping towers, cross-flow and countercurrent. In TOWERS a cross-flow tower, the solvent gas (air) enters along the entire depth of fill and flows through the packing, as the alkaline wastewater flows it may be more economical to use alternate downward. A countercurrent tower draws air ammonia removal techniques, such as steam through openings at the bottom, as wastewater is stripping or biological methods. Air stripping may pumped to the top of a packed tower. Free also be used to remove many hydrophobic organic ammonia (NH3) is stripped from falling water molecules (Nutrient Control, 1983). droplets into the air stream, then discharged to the atmosphere. -

Ozonedisinfection.Pdf

ETI - Environmental Technology Initiative Project funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under Assistance Agreement No. CX824652 What is disinfection? Human exposure to wastewater discharged into the environment has increased in the last 15 to 20 years with the rise in population and the greater demand for water resources for recreation and other purposes. Disinfection of wastewater is done to prevent infectious diseases from being spread and to ensure that water is safe for human contact and the environment. There is no perfect disinfectant. However, there are certain characteristics to look for when choosing the most suitable disinfectant: • Ability to penetrate and destroy infectious agents under normal operating conditions; • Lack of characteristics that could be harmful to people and the environment; • Safe and easy handling, shipping, and storage; • Absence of toxic residuals, such as cancer-causing compounds, after disinfection; and • Affordable capital and operation and maintenance (O&M) costs. What is ozone disinfection? One common method of disinfecting wastewater is ozonation (also known as ozone disinfection). Ozone is an unstable gas that can destroy bacteria and viruses. It is formed when oxygen molecules (O2) collide with oxygen atoms to produce ozone (O3). Ozone is generated by an electrical discharge through dry air or pure oxygen and is generated onsite because it decomposes to elemental oxygen in a short amount of time. After generation, ozone is fed into a down-flow contact chamber containing the wastewater to be disinfected. From the bottom of the contact chamber, ozone is diffused into fine bubbles that mix with the downward flowing wastewater. See Figure 1 on page 2 for a schematic of the ozonation process. -

Water Workforce Renewing

RENEWING THE WATER WORKFORCE Improving water infrastructure and creating a pipeline to opportunity JOSEPH KANE AND ADIE TOMER, JUNE 2018 BROOKINGS METROPOLITAN POLICY PROGRAM 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary 4 Introduction 6 Background 8 Methodology 12 Findings 15 Implications 34 Recommendations 39 Conclusion 50 Appendix A: Water Workforce methodology 60 RENEWING THE WATER WORKFORCE 3 SUMMARY s the U.S. economy continues to grow, many communities are struggling to translate this growth into more equitable and inclusive employment opportunities. Simultaneously, many of the Anation’s water infrastructure assets are in urgent need of repair, maintenance, and restoration. Yet the workers capable of carrying out these efforts are in short supply due to an aging workforce eligible for retirement and the lack of a pipeline for new talent. However, addressing these two challenges operating, and governing U.S. water together offers an enormous infrastructure and infrastructure, spanning a variety of economic opportunity. Constructing, operating, industries and regions. Water utilities employ designing, and governing water infrastructure many workers, but multiple other industries systems demands a skilled workforce, and and establishments, including engineering firms hiring a diverse workforce can support greater and construction contractors, are essential to economic mobility. To unlock this opportunity, the water sector too. Collectively, the water local, state, and national leaders must work workforce fills 212 different occupations—from together to better understand current workforce positions in the skilled trades like electricians challenges and develop new techniques to hire, and technicians to financial, administrative, train, and retain water workers. and management positions—that are found everywhere, from big metropolitan markets to By analyzing occupational employment data, smaller rural areas. -

BEYOND the STATUS QUO: 2015 EQB Water Policy Report

BEYOND THE STATUS QUO: 2015 EQB Water Policy Report LAKE ST. CROIX TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 4 Health Equity and Water. 5 GOAL #1: Manage Water Resources to Meet Increasing Demands . .6 GOAL #2: Manage Our Built Environment to Protect Water . 14 GOAL #3: Increase and Maintain Living Cover Across Watersheds .. 20 GOAL #4: Ensure We Are Resilient to Extreme Rainfall . .28 Legislative Charge The Environmental Quality Board is mandated to produce a five year water Contaminants of Emerging Concern . .34 policy report pursuant to Minnesota Statutes, sections 103A .204 and 103A .43 . Minnesota’s Water Technology Industry . 36 This report was prepared by the Environmental Quality Board with the Board More Information . .43 of Water and Soil Resources, Department of Agriculture, Department of Employment and Economic Development, Department of Health, Department Appendices available online: of Natural Resources, Department of Transportation, Metropolitan Council, • 2015 Groundwater Monitoring Status Report and Pollution Control Agency . • Five-Year Assessment of Water Quality Degradation Trends and Prevention Efforts Edited by Mary Hoff • Minnesota’s Water Industry Economic Profile Graphic Design by Paula Bohte • The Agricultural BMP Handbook for Minnesota The total cost of preparing this report was $76,000 • Water Availability Assessment Report 2 Beyond the Status Quo: 2015 EQB Water Policy Report Minnesota is home to more than 10,000 lakes, 100,000 miles of rivers and streams, and abundant groundwater resources. However, many of these waters are not clean enough. In 2015, we took a major step toward improving our water by enacting a law that protects water quality by requiring buffers on more than 100,000 acres of land adjacent to water. -

Introduction to Co2 Chemistry in Sea Water

INTRODUCTION TO CO2 CHEMISTRY IN SEA WATER Andrew G. Dickson Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii Monthly Average Carbon Dioxide Concentration Data from Scripps CO Program Last updated August 2016 2 ? 410 400 390 380 370 2008; ~385 ppm 360 350 Concentration (ppm) 2 340 CO 330 1974; ~330 ppm 320 310 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 Year EFFECT OF ADDING CO2 TO SEA WATER 2− − CO2 + CO3 +H2O ! 2HCO3 O C O CO2 1. Dissolves in the ocean increase in decreases increases dissolved CO2 carbonate bicarbonate − HCO3 H O O also hydrogen ion concentration increases C H H 2. Reacts with water O O + H2O to form bicarbonate ion i.e., pH = –lg [H ] decreases H+ and hydrogen ion − HCO3 and saturation state of calcium carbonate decreases H+ 2− O O CO + 2− 3 3. Nearly all of that hydrogen [Ca ][CO ] C C H saturation Ω = 3 O O ion reacts with carbonate O O state K ion to form more bicarbonate sp (a measure of how “easy” it is to form a shell) M u l t i p l e o b s e r v e d indicators of a changing global carbon cycle: (a) atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) from Mauna Loa (19°32´N, 155°34´W – red) and South Pole (89°59´S, 24°48´W – black) since 1958; (b) partial pressure of dissolved CO2 at the ocean surface (blue curves) and in situ pH (green curves), a measure of the acidity of ocean water. -

National Primary Drinking Water Regulations

National Primary Drinking Water Regulations Potential health effects MCL or TT1 Common sources of contaminant in Public Health Contaminant from long-term3 exposure (mg/L)2 drinking water Goal (mg/L)2 above the MCL Nervous system or blood Added to water during sewage/ Acrylamide TT4 problems; increased risk of cancer wastewater treatment zero Eye, liver, kidney, or spleen Runoff from herbicide used on row Alachlor 0.002 problems; anemia; increased risk crops zero of cancer Erosion of natural deposits of certain 15 picocuries Alpha/photon minerals that are radioactive and per Liter Increased risk of cancer emitters may emit a form of radiation known zero (pCi/L) as alpha radiation Discharge from petroleum refineries; Increase in blood cholesterol; Antimony 0.006 fire retardants; ceramics; electronics; decrease in blood sugar 0.006 solder Skin damage or problems with Erosion of natural deposits; runoff Arsenic 0.010 circulatory systems, and may have from orchards; runoff from glass & 0 increased risk of getting cancer electronics production wastes Asbestos 7 million Increased risk of developing Decay of asbestos cement in water (fibers >10 fibers per Liter benign intestinal polyps mains; erosion of natural deposits 7 MFL micrometers) (MFL) Cardiovascular system or Runoff from herbicide used on row Atrazine 0.003 reproductive problems crops 0.003 Discharge of drilling wastes; discharge Barium 2 Increase in blood pressure from metal refineries; erosion 2 of natural deposits Anemia; decrease in blood Discharge from factories; leaching Benzene -

Ensuring Availability and Sustainable Management Of

Issue brief SDG 6 © Dan-Roizer ENSURING AVAILABILITY AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF WATER AND SANITATION FOR ALL Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) – Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all – confirms the importance of water and sanitation in the global political agenda. Building on the relevant Millennium Development Goal, SDG 6 addresses the sustainability of access to water and sanitation by focusing on the quality, availability and management of freshwater resources. The individual targets of SDG 6 Environmental dimension of UN Environment and SDG 6 cover the entire water cycle and its SDG 6 interconnections: As the global environmental authority, the SDG 6 recognizes that countries’ social United Nations Environment Programme ➡ 6.1: provision of drinking water development and economic prosperity (UN Environment) connects the issue of depend on the sustainable management of freshwater to other aspects of sustainable ➡ 6.2: sanitation and hygiene freshwater resources and ecosystems. development, such as oceans, land and services SDG 6 acknowledges that ecosystems and agriculture. This work entails building their inhabitants, including humans, are national capacity to monitor freshwater ➡ 6.3: treatment and reuse of water users and that their activities on land ecosystem health, including water wastewater and ambient can compromise the quality and availability quality, facilitating integrated water water quality of fresh water. resources management processes and ➡ 6.4: water-use efficiency and the implementation thereof, and providing scarcity The water-related ecosystems addressed guidelines and inputs for country-level in SDG 6 include wetlands, rivers, aquifers action to protect and restore freshwater ➡ 6.5: integrated water resources and lakes, which sustain a high level of ecosystems at the national level. -

Municipal and Industrial Water Supply ! I

APPENDIXES TO THE MAIN REPORT LOWER COLORADO RIDlON APPENDIX I- HISTORY OF STUDY APPENDIX II - THE HEGION APPENDIX III - LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL ENVIRONMENT APPENDIX IV - ECONOMIC BASE AND PROJECTIONS APPENDIX V- WATER RESOURCES APPENDIX VI - LAND RESOURCES AND USE APPENDIX VII - MINERAL RESOURCES APPENDIX VIII - WATERSHED MANAGEMENT APPENDIX IX - FLOOD CONTROL APPENDIX X- IRRIGATION AND DRAINAGE APPENDIX XI - MUNICIPAL AND INDUSTRIAL WATER APPENDIX XII - RECREATION APPENDIX XIII - FISH AND WILDLIFE APPENDIX XIV - ELECTRIC POWER APPENDIX XV - WATER QUALITY, POLLUTION CONTROL, AND HEALTH FACTORS APPENDIX XVI - SHORELINE PROTECTION AND DEVELOPMENT (NOT APPLICABLE) APPENDIX XVII - NAVIGATION (NOT APPLICABLE) APPENDIX XVIII - GENERAL PROGRAM AND ALTERNATIVES IIII/iliIII/lllillllIIII1I111IIIII1II11II!IIIII LCR[)1855 LOWER COLORADO REGION COMPREHENSIVE FRAMEWORK STUDY APPENDIX XI MUNICIPAL AND INDUSTRIAL WATER SUPPLY ! I This report of the Lower Colorado Region Framework Study State Federal Interagency Group was prepared at field-level and presents the water and related land resources of the Lower Colorado Region. This report is subject to review by the interested Federal agencies at the departmental level, by the Governors of the affected States, and by the Water Resources Council prior to its transmittal to the Congress for its consideration. JUNE 1971 --"---- INDEX MAP EXPLANATION ---- Lower Colorado Region boundary --- Subregion boundary CD Lower Moin Stem o Little Colorado ® Gila .. ... .... Lower Colorado Basin boundary ~ Existing dam o"d reservoir 18:&'41 Existing dam o"d Intermittent lake COMPREHENSIVE FRAMEWORK STUDY LOWER COLORADO REGION - HYDROLOGIC GENERAL LOCATION MAP MAP NO. 1019-314-45 " SCALE· OF MILES " This appendix prepared by the MUNICIPAL AND INDUSTRIAL WATER SUPPLY WORKGROUP of the LOWER COLORADO REGION STATE-FEDERAL INTERAGENCY GROUP for the PACIFIC SOUTHWEST INTERAGENCY COMMITTEE WATER RESOURCES COUNCIL Workgroup Members Robert H. -

Creating a Water and Wastewater Educational Program with Incorporated Experiential Training

AC 2012-5150: CREATING A WATER AND WASTEWATER EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM WITH INCORPORATED EXPERIENTIAL TRAINING Mr. Joseph Lee Gutenson, Western Kentucky University Joseph Gutenson is an Environmental Support Specialist with the Center for Water Resource Studies at Western Kentucky University. During his brief professional career he has participated in the construction of TMDL reports for the Panther Creek and Long Falls Creek Watersheds and site reconnaissance for the Bacon Creek TMDL. He has also participated in research related to the water industries workforce and serves as a presence for the Water Training Institute’s recruitment efforts. His present work includes aiding in the creation of a software packaged, created with funding from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), that will assist drinking water utilities in decontaminating there system after a natural or intentional contamination event. He graduated in December of 2010, magna cum laude, from Western Kentucky University with a degree in Geography, with an emphasis in Sustainable Development and a minor in Economics. Joseph is currently taking graduate coursework at Western Kentucky University. Ms. Jana Fattic, Western Kentucky University Dr. Andrew N.S. Ernest, Western Kentucky University c American Society for Engineering Education, 2012 Creating a Water and Wastewater Educational Program with Incorporated Experiential Training Abstract The EPA requires in the Final Guidelines for the Certification and Recertification of the Operators of Community and Nontransient Noncommunity Public Water Systems Notice (1999) that states and US territories establish some sort of experiential or on-the-job training requirement for incumbent water or wastewater operators before they can legally become licensed professionals. -

51. Astrobiology: the Final Frontier of Science Education

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 51 - Summer 2000 © 2000, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. Astrobiology: The Final Frontier of Science Education by Jodi Asbell-Clarke and Jeff Lockwood What (or Whom) Are We Looking For? Where Do We Look? Lessons from Our Past The Search Is On What Does the Public Have to Learn from All This? A High School Curriculum in Astrobiology Astrobiology seems to be all the buzz these days. It was the focus of the ASP science symposium this summer; the University of Washington is offering it as a new Ph.D. program, and TERC (Technical Education Research Center) is developing a high school integrated science course based on it. So what is astrobiology? The NASA Astrobiology Institute defines this new discipline as the study of the origin, evolution, distribution, and destiny of life in the Universe. What this means for scientists is finding the means to blend research fields such as microbiology, geoscience, and astrophysics to collectively answer the largest looming questions of humankind. What it means for educators is an engaging and exciting discipline that is ripe for an integrated approach to science education. Virtually every topic that one deals with in high school science is embedded in astrobiology. What (or Whom) Are We Looking For? Movies and television shows such as Contact and Star Trek have teased viewers with the idea of life on other planets and even in other galaxies. Illustration courtesy of and © 2000 by These fictional accounts almost always deal with intelligent beings that have Kathleen L. -

Ecological Sustainability Within California's Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog Clark University, [email protected]

Clark University Clark Digital Commons International Development, Community and Master’s Papers Environment (IDCE) 5-2018 Ecological Sustainability within California's Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog Clark University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers Part of the Environmental Policy Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Physical and Environmental Geography Commons, and the Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons Recommended Citation Hertog, Cory, "Ecological Sustainability within California's Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program" (2018). International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE). 195. https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers/195 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Master’s Papers at Clark Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE) by an authorized administrator of Clark Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Ecological Sustainability within California’s Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog May 2018 A Master’s Paper Submitted to the faculty of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science of Environmental Science and Policy in the department of International Development, Community, and Environment and a Master of Business Administration in the Graduate School of Management And accepted on the recommendation of Dominik Kulakowski - Ph.D. Will O’Brien - J.D., M.B.A Graduate School of Geography Graduate School of Management Abstract Ecological Sustainability within California’s Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog Forest Carbon offsets are being used as a climate change mitigation strategy in multiple programs around the world. -

Higher Education in the Water Sector: a Global Overview

UNU-INWEH REPORT SERIES 07 Higher Education in the Water Sector: A Global Overview Colin Mayfield www.inweh.unu.edu About UNU-INWEH UNU-INWEH’s mission is to help resolve pressing water challenges that are of concern to the United Nations, its Member States, and their people, through critical analysis and synthesis of existing bodies of scientific discovery; targeted research that identifies emerging policy issues; application of on-the-ground scalable science-based solutions to water issues; and global outreach. UNU-INWEH carries out its work in cooperation with the network of other research institutions, international organisations and individual scholars throughout the world. UNU-INWEH is an integral part of the United Nations University (UNU) – an academic arm of the UN, which includes 13 institutes and programmes located in 12 countries around the world, and dealing with various issues of development. UNU-INWEH was established, as a public service agency and a subsidiary body of the UNU, in 1996. Its operations are secured through long-term host-country and core-funding agreements with the Government of Canada. The Institute is located in Hamilton, Canada, and its facilities are supported by McMaster University. About UNU-INWEH Report Series UNU-INWEH Reports normally address global water issues, gaps and challenges, and range from original research on specific subject to synthesis or critical review and analysis of a problem of global nature and significance. Reports are published by UNU-INWEH staff, in collaboration with partners, as / when applicable. Each report is internally and externally peer-reviewed. UNU-INWEH Reports are an open access publication series, available from the Institute’s web site and in hard copies.