The Buffalo Nickel the Buffalo Nickel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Collect Coins a Fun, Useful, and Educational Guide to the Hobby

$4.95 Valuable Tips & Information! LITTLETON’S HOW TO CCOLLECTOLLECT CCOINSOINS ✓ Find the answers to the top 8 questions about coins! ✓ Are there any U.S. coin types you’ve never heard of? ✓ Learn about grading coins! ✓ Expand your coin collecting knowledge! ✓ Keep your coins in the best condition! ✓ Learn all about the different U.S. Mints and mint marks! WELCOME… Dear Collector, Coins reflect the culture and the times in which they were produced, and U.S. coins tell the story of America in a way that no other artifact can. Why? Because they have been used since the nation’s beginnings. Pathfinders and trendsetters – Benjamin Franklin, Robert E. Lee, Teddy Roosevelt, Marilyn Monroe – you, your parents and grandparents have all used coins. When you hold one in your hand, you’re holding a tangible link to the past. David M. Sundman, You can travel back to colonial America LCC President with a large cent, the Civil War with a two-cent piece, or to the beginning of America’s involvement in WWI with a Mercury dime. Every U.S. coin is an enduring legacy from our nation’s past! Have a plan for your collection When many collectors begin, they may want to collect everything, because all different coin types fascinate them. But, after gaining more knowledge and experience, they usually find that it’s good to have a plan and a focus for what they want to collect. Although there are various ways (pages 8 & 9 list a few), building a complete date and mint mark collection (such as Lincoln cents) is considered by many to be the ultimate achievement. -

Ft. Myers Rare Coins and Paper Money Auction (08/23/14) 8/23/2014 13% Buyer's Premium 3% Cash Discount AU3173 AB1389

Ft. Myers Rare Coins and Paper Money Auction (08/23/14) 8/23/2014 13% Buyer's Premium 3% Cash Discount AU3173 AB1389 www.gulfcoastcoin.com LOT # LOT # 400 1915S Pan-Pac Half Dollar PCGS MS67 CAC Old Holder 400r 1925 Stone Mountain Half Dollar NGC AU 58 1915 S Panama-Pacific Exposition 1925 Stone Mountain Memorial Half Dollar Commemorative Half Dollar PCGS MS 67 Old NGC AU 58 Holder with CAC Sticker - Toned with Min. - Max. Retail 55.00 - 65.00 Reserve 45.00 Beautiful Colors Min. - Max. Retail 19,000.00 - 21,000.00 Reserve 17,000.00 400t 1925 S California Half Dollar NGC MS 63 1925 S California Diamond Jubilee Half Dollar NGC MS 63 400c 1918 Lincoln Half Dollar NGC MS 64 Min. - Max. Retail 215.00 - 235.00 Reserve 1918 Lincoln Centennial Half Dollar NGC MS 190.00 64 Min. - Max. Retail 170.00 - 185.00 Reserve 150.00 401 1928 Hawaii Half Dollar NGC AU 58 1928 Hawaiian Sesquicentennial Half Dollar NGC AU 58 400e 1920 Pilgrim Half Dollar NGC AU 58 Min. - Max. Retail 1,700.00 - 2,000.00 Reserve 1920 Pilgrim Tercentenary Half Dollar NGC 1,500.00 AU 58 Min. - Max. Retail 68.00 - 75.00 Reserve 55.00 401a 1928 Hawaiian Half Dollar PCGS MS 65 CAC 1928 Hawaiian Sesquicentennial 400g 1921 Alabama Half Dollar NGC MS 62 Commemorative Half Dollar PCGS MS 65 with 1921 Alabama Centennial Commemorative Half CAC Sticker Dollar NGC MS 62 Min. - Max. Retail 4,800.00 - 5,200.00 Reserve Min. - Max. -

United States Mint

United States Mint Program Summary by Budget Activity Dollars in Thousands FY 2012 FY 2013 FY 2014 FY 2012 TO FY 2014 Budget Activity Actual Estimated Estimated $ Change % Change Manufacturing $3,106,304 $3,525,178 $2,937,540 ($168,764) -5.43% Total Cost of Operations $3,106,304 $3,525,178 $2,937,540 ($168,764) -5.43% FTE 1,788 1,844 1,874 86 4.81% Summary circulating coins in FY 2014 to meet the The United States Mint supports the needs of commerce. Department of the Treasury’s strategic goal to enhance U.S. competitiveness and promote Numismatic Program international financial stability and balanced Bullion – Mint and issue bullion coins global growth. while employing precious metal purchasing strategies that minimize or Since 1996, the United States Mint operations eliminate the financial risk that can arise have been funded through the Public from adverse market price fluctuations. Enterprise Fund (PEF), established by section 522 of Public Law 104–52 (codified at section Other Numismatic Products - Produce and 5136 of Title 31, United States Code). The distribute numismatic products in United States Mint generates revenue through sufficient quantities, through appropriate the sale of circulating coins to the Federal channels, and at the lowest prices Reserve Banks (FRB), numismatic products to practicable, to make them accessible, the public and bullion coins to authorized available, and affordable to people who purchasers. Both operating expenses and choose to purchase them. Design, strike capital investments are associated with the and prepare for presentation Congressional production of circulating and numismatic Gold Medals and commemorative coins, as coins and coin-related products. -

Buffalo Hunt: International Trade and the Virtual Extinction of the North American Bison

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES BUFFALO HUNT: INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND THE VIRTUAL EXTINCTION OF THE NORTH AMERICAN BISON M. Scott Taylor Working Paper 12969 http://www.nber.org/papers/w12969 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2007 I am grateful to seminar participants at the University of British Columbia, the University of Calgary, the Environmental Economics workshop at the NBER Summer Institute 2006, the fall 2006 meetings of the NBER ITI group, and participants at the SURED II conference in Ascona Switzerland. Thanks also to Chris Auld, Ed Barbier, John Boyce, Ann Carlos, Charlie Kolstad, Herb Emery, Mukesh Eswaran, Francisco Gonzalez, Keith Head, Frank Lewis, Mike McKee, and Sjak Smulders for comments; to Michael Ferrantino for access to the International Trade Commission's library; and to Margarita Gres, Amanda McKee, Jeffrey Swartz, Judy Hasse of Buffalo Horn Ranch and Andy Strangeman of Investra Ltd. for research assistance. Funding for this research was provided by the SSHRC. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2007 by M. Scott Taylor. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Buffalo Hunt: International Trade and the Virtual Extinction of the North American Bison M. Scott Taylor NBER Working Paper No. 12969 March 2007 JEL No. F1,Q2,Q5,Q56 ABSTRACT In the 16th century, North America contained 25-30 million buffalo; by the late 19th century less than 100 remained. -

Initial Layout

he bison or buffalo is an enduring with the people who inhabited the Central typically located on built-in altars oppo- animal, having come from the Plains and its utility to them, it is not sur- site the east-facing entrances, so that the Tbrink of extinction in the latter part prising that the bison was an integral part morning light would fall upon them (see of the nineteenth century to a relatively of their lives. Buffalo were central char- earthlodge sketch at right). Such an altar substantial population today. The bison is acters in stories that were told of their can be seen at the Pawnee Indian Village also a living symbol, or icon, with mul- beginnings as tribal people living on Museum State Historic Site near Repub- tiple meanings to different people. earth, and bison figured prominently in lic, Kansas. Bison were also represented The association of bison with Ameri- ceremonies designed to insure the tribe’s in dances, such as the Buffalo Lodge can Indians is a firmly established and continued existence and good fortune. dance for Arapaho women; there were widely known image–and with good rea- Bison bone commonly is found as buffalo societies within tribal organiza- son. Archeological evidence and histori- food refuse in prehistoric archeological tions; and bison were represented in tribal cal accounts show that American Indians sites; but bison bones, in particular bison fetishes, such as the sacred Buffalo Hat or living in the Plains hunted bison for a skulls, also are revealed as icons. Per- Cap of the Southern Cheyenne. -

INFORMATION BULLETIN #50 SALES TAX JULY 2017 (Replaces Information Bulletin #50 Dated July 2016) Effective Date: July 1, 2016 (Retroactive)

INFORMATION BULLETIN #50 SALES TAX JULY 2017 (Replaces Information Bulletin #50 dated July 2016) Effective Date: July 1, 2016 (Retroactive) SUBJECT: Sales of Coins, Bullion, or Legal Tender REFERENCE: IC 6-2.5-3-5; IC 6-2.5-4-1; 45 IAC 2.2-4-1; IC 6-2.5-5-47 DISCLAIMER: Information bulletins are intended to provide nontechnical assistance to the general public. Every attempt is made to provide information that is consistent with the appropriate statutes, rules, and court decisions. Any information that is inconsistent with the law, regulations, or court decisions is not binding on the department or the taxpayer. Therefore, the information provided herein should serve only as a foundation for further investigation and study of the current law and procedures related to the subject matter covered herein. SUMMARY OF CHANGES Other than nonsubstantive, technical changes, this bulletin is revised to clarify that sales tax exemption for certain coins, bullion, or legal tender applies to coins, bullion, or legal tender that would be allowable investments in individual retirement accounts or individually-directed accounts, even if such coins, bullion, or legal tender was not actually held in such accounts. INTRODUCTION In general, an excise tax known as the state gross retail (“sales”) tax is imposed on sales of tangible personal property made in Indiana. However, transactions involving the sale of or the lease or rental of storage for certain coins, bullion, or legal tender are exempt from sales tax. Transactions involving the sale of coins or bullion are exempt from sales tax if the coins or bullion are permitted investments by an individual retirement account (“IRA”) or by an individually-directed account (“IDA”) under 26 U.S.C. -

Read It Online

Serving the Numismatic Community Since 1959 Village Coin Shop Catalog 2020-2021 Vol. 59 www.villagecoin.com • P.O. Box 207 • Plaistow, NH 03865-0207 2020 U.S. Gold Eagles Half Dollar Commemoratives • Brilliant Uncirculated All in original box with COA unless noted **In Capsules Only • Call For Prices USGE1 . .1/10 oz Gold Eagle USGE2 . .1/4 oz Gold Eagle USGE3 . .1/2 oz Gold Eagle USGE4 . .1 oz Gold Eagle ITEM DESCRIPTION GRADE PRICE CMHD82B7 . .1982-D Washington . BU . $16 .00 Commemorative Sets CMHD82C8 . .1982-S Washington . Proof . 16 .50 CMHD86B7 . .1986-D Statue of Liberty** . BU . 5 .00 CMHD86C8 . .1986-S Statue of Liberty** . Proof . 4 .00 CMHD91C7 . .1991-D Mount Rushmore . BU . 20 .00 CMHD91C8 . .1991-S Mount Rushmore . Proof . 28 .00 CMHD92C8 . .1992-S Olympic . BU . 35 .00 CMHD92C8 . .1992-S Olympic . Proof . 35 .00 CMHD93D7 . .1993-W Bill of Rights . BU . 40 .00 CMHD93C8 . .1993-S Bill of Rights . Proof . 35 .00 CMHD93A7 . .1993-P World War II . BU . 30 .00 CMHD93A8 . .1993-P World War II . Proof . 36 .00 CMHD94B7 . .1994-D World Cup . BU . 13 .00 ITEM DESCRIPTION GRADE PRICE CMHD94A8 . .1994-P World Cup . Proof . 13 .00 Two-Coin Half Dollar And Silver Dollar Sets CMHD95A7 . .1995-P Civil War . BU . 63 .00 CMTC86A7 . .1986 Statue of Liberty . BU . $ 39 .00 CMHD95C9 . .1995-S Civil War . Proof . 63 .00 CMTC86A8 . .1986 Statue of Liberty . Proof . 39 .00 CMHD95C7 . .1995-S Olympic Basketball . BU . 27 .50 CMTC86C8 . .1989 Congressional . Proof . 49 .00 CMHD95C8 . .1995-S Olympic Basketball . Proof . 35 .00 CMHD95C7 . .1995-S Olympic Baseball . -

Notice of Sale of Personal Property Under Execution

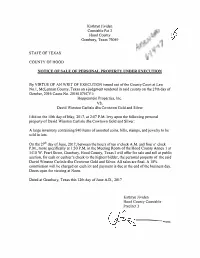

Kathryn Jividen Constable Pct 3 Hood County Granbury, Texas 76049 STATE OF TEXAS COUNTY OF HOOD NOTICE OF SALE OF PERSONAL PROPERTY UNDER EXECUTION By VIRTUE OF AN WRIT OF EXECUTION issued out ofthe County Court at Law No. I, McLennan County, Texas on a judgmentrend ered in said county on the 27th day of October, 2016 Cause No. 20161075CVI: Hoppenstein Properties, Inc. vs. David Winston Carlisle dba Cowtown Gold and Silver I did on the 10th day of May, 2017, at 2:07 P.M. levy upon the following personal property of David Winston Carlisle dba Cowtown Gold and Silver: A large inventory containing 940 items of assortedcoins, bills, stamps, and jewelry to be sold in lots. On the 2th day of June, 2017, between the hours often o'clock A.M. and fouro' clock P.M., more specifically at I :30 P.M. in the Meeting Room of the Hood County Annex 1 at 1410 W. Pearl Street, Granbury, Hood County, Texas I will offer forsale and sell at public auction, for cash or cashier's check to the highest bidder, the personal propertyof the said David Winston Carlisle dba Cowtown Gold and Silver. All sales are final.A 10% commission will be charged on each lot and payment is due at the end of the business day. Doors open forviewing at Noon. Dated at Granbury, Texas this 12th day of June A.O., 2017 Kathryn Jividen Hood County Constable Precinct 3 --=-==--- Lot 1 Lot 4 #29, 43, 66, 69 Plastic Bin with Pennies The Complete Collection of uncirculated Sacagawea 293 .50cent rolls of pennies Golden Dollars PCS Stamps & Coins .41 cents loose pennies The Complete Collection -

Coin Catalog 3-31-18 Lot # Description Lot # 1

COIN CATALOG 3-31-18 LOT # DESCRIPTION LOT # 1. 20 Barber Dimes 1892-1916 44. 1944S 50 Centavo Phillipine WWII Coinage GEM BU 2. 16 V-Nickels 1897-1912 45. 1956D Rosy Dime MS64 NGC 3. 8 Mercury Dimes 1941-1942S 46. 1893 Isabella Quarter CH BU Low Mintage 24,214 4. 16 Pcs. of Military Script 47. 1897 Barber Quarter CH BU 5. 1928A "Funny Back" $1 Silver Certificate 48. 10K Men's Gold Harley Davidson Ring W/Box 6. 1963B "Barr Note" $1 Bill W/Star 49. Roll of 1881-0 Morgan Dollars CH UNC 7. 40 Coins From Europe 50. 1954P,D,S Mint Sets in Capital Holder GEM 8. 4 Consecutively Numbered 2003A Green Seal $2 Bills 51. Roll of 1879 Morgan Dollars CH UNC 9. 1863 Indian Cent CH UNC 52. Colonial Rosa Americana Two Pence RARE 10. 1931D Lincoln Cent CH UNC KEY 53. 1911S Lincoln Cent VF20 PCGS 11. 1943 Jefferson Nickel MS65 Silver 54. 1919S " MS65 12. 1953 " PF66 Certified 55. 1934D " " 13. 1876S Trade Dollar CH UNC Rare High Grade 56. 1907 Indian Cent GEM PROOF 14. 1889S Morgan Dollar MS65 Redfield Collection KEY 57. 1903-0 Barber Dime XF45 Original 15. 1885S " CH BU KEY 58. 1917S Reverse Walking Liberty Half F15 16. 1880-0 " MS62 PCGS 59. 1926D Peace Dollar MS65+ 17. 1934D Peace Dollar MS62 NGC 60. 1987 Proof Set 18. 2 1923 Peace Dollar CH BU Choice 61. 1854 Seated Half AU+ 19. 1934 $100 FRN FR# 2152-A VF 62. 1893 Isabella Quarter MS63 Low Mintage 24,214 20. -

Coin Catalog 1-26-19 Lot # Description 1

COIN CATALOG 1-26-19 LOT # DESCRIPTION 1. Coin Paper Weight 44. 1909S Lincoln Cent VF+ KEY 2. 1962 Washington Quarter PR67 45. 1919 " BU 3. 1964 " " 46. 1931S " CH AU KEY RARE 4. 2009 Inaugural Ceremony Lincoln Cent Cert. 47. 1878 7/8 TF Morgan Dollar CH AU 5. 1999 SBA Dollar Proof 48. 1878S Morgan Dollar CH BU 6. 2004 ASE MS69 PCGS 49. 1879 " AU 7. 140 Wheat Cents in Bag 50. 1879-0 " BU 8. 1835 Half Cent XF 51. 1880S " MS65 9. 1857 Flying Eagle Cent AU 52. 1922 Peace Dollar BU 10. 1859 Indian Cent AU 53. 1922S " BU 11. 1863 " AU 54. 1923 " BU 12. 1874 " CH UNC Rare High Grade 55. 4 Peace Dollars 1922-1924 MS63 13. 1866 " " " 56. 1847 Lg. Cent AU+ 14. 1902 " " 57. 1855 " AU 15. 1832 Half Cent XF Low Mintage 58. 1856 " AU 16. 1832 Lg. Cent AU 59. 1949 Franklin Half MS64 KEY 17. 1850 " MS63 RB 60. 1946 Walking Liberty Half MS64 18. 1854 " AU 61. 1938D " VF KEY 19. 1931S Lincoln Cent MS63 KEY RARE 62. 4 Peace Dollars 1922-1924 MS63 20. 4 Peace Dollars 1922-1924 MS63 63. 1859 Indian Cent XF45 Original 21. 1948D Franklin Half MS65+ FBL 64. 1914S Lincoln Cent MS64+ Original Toning RARE 22. 1954D " " " 65. 1920D " " Typical Weak Mint Mark 23. 1948D Washington Quarter MS67 GEM 66. 1806 Lg. Cent Lg. 6, Stems AG3 24. 1948S " MS66+ " 67. 1917D T-1 Standing Quarter XF45 Original Scarce 25. Ladies Gold Chain & Tiger Eye Pendant 68. 1844-0 Seated Half CH AU Toned Rare 26. -

Spring/Summer

friends OF THE SAINT-GAUDENS MEMORIAL CORNISH I NEW HAMPSHIRE I SUMMER 2007 (Right Augustus Saint-Gaudens in his Paris Studio, 1898. Sketch of the Amor Caritas IN THIS ISSUE SAINT-GAUDENS’ in the background. Saint-Gaudens’ Numismatic Legacy I 1 NUMISMATIC LEGACY (Below) Obverse of the high relief The Model for the 1907 Double Eagle I 4 The precedent that President 1907 Twenty Dollar A Little Known Treasure I 5 Gold Coin. Saint-Gaudens Film & Symposium I 6 Theodore Roosevelt established, Concerts and Exhibits I 7 of having academically trained Coin Exhibition I 8 sculptors design U.S. coinage, resulted in a series of remarkable coins. Many of these were created FROM THE MEMORIAL by five artists who trained under AND THE SITE Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Archival photo DEAR FRIENDS AND ANS MEMBERS, Bela Pratt (1867-1917) This Friends Newsletter from Connecticut, first studied with Saint-Gaudens In 1907, Pratt was encouraged by is dedicated to the centennial at the Art Students League Dr. William Sturgis Bigelow (185 0-1926), of Saint-Gaudens’ Ten and in New York City. He then a prominent collector of Oriental art and Twenty Dollar Gold Coins moved to Paris, where he an acquaintance of President Theodore studied under Jean Falguière (1831-1900) Roosevelt, to redesign the Two and a Half and his numismatic legacy. and Henri-Michel-Antoine Chapu (183 3- and Five Dollar Gold Coins. Pratt’s designs Augustus Saint-Gaudens, at the request 1891) at the École des Beaux-Arts. Saint- were the first American coins to have an of President Theodore Roosevelt, was the Gaudens was the first American accepted incused design, which is a relief in reverse . -

COIN AUCTION by Baxa Auctions, LLC Sunday, April 7, 2019 Kenwood Hall, 900 Greeley, Salina, KS Auction Starts at 12:30, Doors Open at 10:30

COIN AUCTION by Baxa Auctions, LLC Sunday, April 7, 2019 Kenwood Hall, 900 Greeley, Salina, KS Auction starts at 12:30, Doors open at 10:30 Note: Payment due immediately after the sale. Please review terms on last page before bidding. Lot # Description Grade Tokens & Misc 1 Silver Certificate Redemption Bullion in Plastic Unc 2 (13) Encased Cents (10-Lincolns, 3-Indian Head) Circ 3 (7) Rectangular Wooden Nickels (1939-1970) Unc 4 (5) Wm. J. Schwartz Hanover, KS Trade Tokens (5c-1$) Circ 5 (4) Coin Design Coasters Unc 6 (4) California $50 Gold Slug Replicas Unc 7 (5) California Souvenir Gold Replicas in Display Case Unc 8 (2) 1961 KS Statehood 3-inch Medals (Silver & Bronze) Unc 9 (2) 1971 Concordia KS 1-inch Medals (Silver & Bronze) Unc 10 1960 P&D Large/Small Date Cent Set in Plastic (4 coins) Unc 11 1960 Proof Large/Small Date Cent Set in Plastic (2 coins) Proof 12 1995-P Unc Bank Set & 1976 Bicentennial Coinage Mixed 13 1979 & 1980 ANA Convention Souvenir Sets (5 $ Coins) Unc Groups 14 (3) Indian Head Cents (1905, 1906, 1907) AU 15 (4) Jefferson Unc 5c (1938-D&S, 1939-D&S) MS63-65 16 (3) 1945-PDS Unc War Nickels Unc 17 (2) 1950-D Unc Jefferson Nickels MS65 18 (23) Proof Jefferson Nickels (1960-1964) (in mint cello) Proof 19 (9) Proof Silver Roosevelt Dimes (1956-1964 1 each) Proof 20 (15) Proof Clad Roosevelt Dimes (1968-1990) Proof 21 (12) Proof Washington Quarters (1959-1990) Proof 22 (6) Proof Kennedy Half Dollars (1964, 68S, 69S, 70S, 88S, 90S) Proof 23 (6) Susan B.