University of Derby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2005 Credit Card Survey

Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage PAID CONSUMER San Francisco, CA Permit # 10402 ACTION NEWS Change Service Requested Summer 2005 • www.consumer-action.org A publication of San Francisco Consumer Action 2005 Credit Card Survey credit card bill late—even once. Late payments are not the only reason issuers Card companies use common ‘risk factors’ impose higher penalty interest rates. Going over your credit limit or bounc- ing a payment check can trigger a rate to impose unfair rate hikes, finds CA increase, too, in addition to hefty fees. The average penalty rate this year is redit card penalty interest rates the way customers handle other credit credit, the rate might be adjusted 24.23%, up from the 2004 average of and universal default rate hikes, accounts. This year, 44.68% of banks downward—although not always to the 21.91%. This increase is probably at- Coften cited as a way for card said they have universal default poli- original rate. tributable to the fact that most penalty companies to manage risk, top the list cies—a slight increase from last year’s Advance notice of default or penalty rates vary with the Prime Rate, and from of unfair credit card practices. In its survey. According to customer service rate increases is not required by law. last year’s survey to this year’s the Prime new credit card study, Consumer Action representatives, the following circum- In many cases, the first time consum- Rate increased two percentage points (CA) uncovered the top reasons that stances, in descending order of impor- ers learn of a rate increase is when they (from 4% to 6%). -

ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority

ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority Vol. XCVIII, No. 49 22nd MAY, 2020 Price RTGS$20,00 General Notice 863 of 2020. CUSTOMS AND EXCISE ACT [CHAPTER 23:02] Zimbabwe Revenue Authority: Notice of Intention to sell Unclaimed Vehicles NOTICE is hereby given in terms of section 39(2) of the Customs and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02], that the following vehicles will be dealt with in terms of section 39(3) and 39(4) of the Customs and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02] if not claimed within 30 days of the publication of this notice. The owners of these vehicles are unknown and the goods will be sold if not claimed within thirty days of the publication of this notice. The vehicles are accident damaged and were abandoned at Vehicle Inspection Depots in Gwanda and Bulawayo. The vehicles are being held at Manica Container Depot, Stand No. 3041, Institute Avenue, Raylton, Bulawayo, and Vehicle Inspection Depot premises in Gwanda. MS. F. MAZANI, 22-5-2020. Commissioner-General Zimbabwe Revenue Authority. Schedule UNCLAIMED VEHICLES DETENTION DATE OF REG ENGINE CHASSIS No MAKE STATUS YEAR LOCATION DETAILS DETENTION NUMBER NUMBER NUMBER Manica TOYOTA Accident Container 1 N/S 023183 14/12/2011 REG# B960ACT UNKNOWN MX75-0004189 Unknown CRESSIDA damaged Depot- Bulawayo HOMEMADE REG# LH- VID - 2 RIH 188365 14/10/2015 UNKNOWN NOT SEEN Unknown LIGHT TRAILER M588GP Gwanda TOYOTA PICK Accident VID - 3 RIH 188395 14/10/2015 REG# PHZ641GP 612160 5R2206954 Unknown UP Damaged Gwanda DATSUN REG# DR- Accident VID - 4 RIH 188394 14/10/2015 A09544 Unknown SEDAN -

METROPOLITAN BANK HOLDING CORP. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on October 25, 2017 Registration No. 333-220805 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 PRE-EFFECTIVE AMENDMENT NO. 1 TO THE FORM S-1 REGISTRATION STATEMENT UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 METROPOLITAN BANK HOLDING CORP. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) New York 6712 13-4042724 (State or other jurisdiction of (Primary Standard Industrial (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Classification Code Number) Identification Number) 99 Park Avenue New York, New York 10016 (212) 365-6700 (Address, Including Zip Code, and Telephone Number, Including Area Code, of Registrant’s Principal Executive Offices) Mark R. DeFazio President and Chief Executive Officer 99 Park Avenue New York, New York 10016 (212) 365-6700 (Address, Including Zip Code, and Telephone Number, Including Area Code, of Agent for Service) Copies to: Gary A. Lax, Esq. Richard D. Truesdell, Jr., Esq. Michael J. Brown, Esq. Shane Tintle, Esq. Megan McKinney, Esq. Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP Luse Gorman, PC 450 Lexington Avenue 5335 Wisconsin Avenue, N.W., Suite 780 New York, New York 10017 Washington, D.C. 20015 (212) 450-4000 (202) 274-2000 Approximate date of commencement of proposed sale to the public: As soon as practicable after this registration statement becomes effective. If any of the securities being registered on this Form are to be offered on a delayed or continuous basis pursuant to Rule 415 under the Securities Act of 1933, check the following box: If this -

Bank Supervision Annual Report - 2017

BANK SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT - 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS GOVERNOR’S FOREWORD ....................................................................................................... 6 DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD .......................................................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW OF MACROECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT ....................................... 10 CHAPTER 2: MAJOR DEVELOPMENTS AND OTHER SUPERVISORY ACTIVITIES IN THE BANKING SECTOR ............................................................................................. 14 CHAPTER 3: CONDITION & PERFORMANCE OF THE BANKING SECTOR .......................... 24 CHAPTER 4: LEGAL & REGULATORY DEVELOPMENTS ...................................................... 54 CHAPTER 5: CONSUMER EDUCATION AND CONSUMER PROTECTION ............................ 56 CHAPTER 6: OUTLOOK ........................................................................................................... 59 APPENDIX 1: FUNCTION AND ORGANIZATION OF BANK SUPERVISION DIVISION .......... 63 APPENDIX 2: MAJOR SUPERVISORY TOOLS AND METHODOLOGIES ............................... 65 APPENDIX 3: REGISTERED BANKING INSTITUTIONS AS AT 31 DECEMBER 2017 ............ 69 APPENDIX 4: STATISTICAL TABLES AS AT 31 DECEMBER 2017 ........................................ 72 2 List of Tables Table 1: Empowerment Facilities Utilisation ..................................................................................................... 20 Table 2: Financial Inclusion Indicators ............................................................................................................. -

Download January 2015 Monetary Policy

JANUARY 2015 MONETARY POLICY STATEMENT Rebalancing the Economy Through Competitiveness and Compliance BY DR. J. P. MANGUDYA GOVERNOR RESERVE BANK OF ZIMBABWE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 GLOBAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS 7 BALANCE OF PAYMENTS DEVELOPMENTS 11 Trade Balance 13 Current, Capital and Financial Account Development 16 Overall Balance of Payments Position 17 DOMESTIC ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS 17 Domestic Output 17 Inflation 18 Deflation (Price Correction) not Deflation 19 Inflation Outlook 20 FINANCIAL SECTOR DEVELOPMENTS 20 Structure and Performance 20 Capitalisation 21 Sector Profitability 23 Financial Intermediation (Deposits & Loans) 23 Sectorial Distribution of Loans & Advances 24 Performance of Microfinance Sector 25 Financial Inclusion 26 Non-performing Loans 28 Financial Stability 28 Distressed Banks 29 Tetrad Investment Bank 30 Metbank 30 AfrAsia Bank Zimbabwe Limited 31 STATUS OF RBZ SUBSIDIARIES 31 Export Credit Guarantee Corporation (ECGC) 31 Homelink 32 Fidelity Printers and Refiners 33 Aurex 35 PROGRESS ON BANKING SECTOR REFORMS AND INITIATIVES 35 Amendments to Banking Act 35 Basel II Implementation 36 Resolution of Non-performing Loans under ZAMCO 37 Consumer Protection 39 Capitalisation of the Reserve Bank 39 Credit Reference Bureau (CRB) 40 Enhancement of the Guideline on Relationship with External Auditors 41 Small Denomination Coins, Bond Coins 42 POLICY MEASURES 43 CONFIDENCE AND PRODUCTION ENHANCEMENT MEASURES 44 Demonetisation of the Zimbabwe Dollar 44 Distribution of Bond Coins 45 Changing Rand Coins for Bond Coins 45 -

CAMEL MINING (PRIVATE) LIMITED Versus METBANK LIMITED and REGISTRAR of DEED and the SHERIFF of the HIGH COURT of ZIMBABWE

1 HH123 -21 HC 4284/20 CAMEL MINING (PRIVATE) LIMITED versus METBANK LIMITED and REGISTRAR OF DEED and THE SHERIFF OF THE HIGH COURT OF ZIMBABWE HIGH COURT OF ZIMBABWE MANGOTA J HARARE, 17 November 2020 & 12 March 2021 Opposed Application T E Gumbo, for the applicant E Musendekwa, for the respondent MANGOTA J: Law is not a static discipline. It moves and changes in accordance with a given society’s stage of development. It changes in such a way that what society regarded as lawful yesterday may not be lawful on the following day and vice versa. Its movement and changes are not without reason. They assist people in whose society the changes and movements occur to resolve disputes which arise between, and amongst, them with a certain degree of clarity. They are, therefore, a dispute-resolving mechanism which society puts into place from time to time for the good of its own members. Where the law is clear and unambiguous, it must be taken as it is. It should not be overstretched to suit the circumstances of any litigant to a dispute. It should, in other words, neither be expanded nor contracted. It should be allowed to assume and retain its ordinary, grammatical meaning or the meaning by which its words, as they appear in a statute or document, are popularly known or understood to mean in every day parlance. It is only where the words which appear in a document are either unclear or ambiguous or are devoid of meaning that the onerous task of giving a possible meaning to them arises. -

Metbank Individual Account Opening Form

APPLICATION TO OPEN A JOINT / PERSONAL ACCOUNT Documents Required 2 passport sized photographs Proof of Residence Payslip / Source of income declaration SECTION 1: DETAILS OF ACCOUNT (Please Tick in Appropriate Box) Tick where applicable: USD ZAR GBP EURO BWP CNY Other (Please Specify) Current Savings Met Save Met Student Met Home Saver Other (Please Specify) Individual Joint Senior Citizen (60 Years +) SECTION 2: PLEASE FILL IN YOUR PERSONAL DETAILS Salutation/Title: Mr Mrs Other First Name (please specify) Maiden Middle Name Name Surname Gender(Tick): Male F emale Marital Status(Tick): Married Single Widowed Country of Birth Nationality Citizenship Residency Tel. number: Date of Birth D D M M Y Y Y Y Home Mobile Business E-mail Residential Address Postal Address Post Code Accommodation(Tick) Rented Provided by employer Owned but mortgaged Owned without mortgage Other (please specify) Number of Dependents Details of dependants (Please ll in table) Name Gender Date of Birth Type of ID (Tick): National ID Passport Drivers Licence National I.D Number (Mandatory) Issue Date D D M M Y Y Y Y Place of Issue District of Birth Issue Date Passport/Drivers Licence Number (of passport or Drivers license) D D M M Y Y Y Y Expiry Date (passport) D D M M Y Y Y Y Place of Issue Issuer Country SECTION 3: EMPLOYMENT DETAILS Profession Education Average Monthly Expenditure Position Held Employment Status: (please tick) Permanent Casual Contract Employer’s Name Employer Contact Person Name Designation Nature of Employer’s Business: (please tick) Manufacturing Mining Transport Commerce Farming Government Self Employed Other (please specify) Employer’s Physical Address Employer’s Postal Address Post Code Period of Employment (Yrs) Gross Monthly Income Net Monthly Income Other Source/s of Income Total Other Income ©Metbank Limited Page 1 of 8 Initials MFG 26 SECTION 4: SPOUSE’S/CO-ACCOUNT HOLDER’S DETAILS Salutation/Title: Mr Mrs Other First Name (Please Specify) Middle Name Maiden Name Country Surname Gender(Tick): Male Female of Birth Nationality Citizenship Residency Tel. -

To Ascertain Risk Exposures, Loan Loss Provisions and Significance

IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM) e-ISSN: 2278-487X, p-ISSN: 2319-7668. Volume 18, Issue 3 .Ver. I (Mar. 2016), PP 73-86 www.iosrjournals.org To Ascertain Risk Exposures, Loan Loss Provisions And Significance Of Internal Controls In The Commercial Banking Sector In Zimbabwe During The Multi-Currency Era (2009 2015) Itumeleng Magadi1, Gibson Blessing Blazo2 1Master Of Science In Banking And Financial Services Degree, Bachelor Of Commerce Honours In Banking Degree, An Institute Of Bankers Of Zimbabwe Diploma (Iobz). He Is A Lecturer – Zou Harare Region. 2Bachelor Of Commerce Honours Degree In Accounting. He Is Into Operations Department At Zimbabwe Open University. Abstract: The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe enforced strict adherence to loan loss provisions and standard risk exposures in implementing Basel 11 in the banking sector. This was due to a huge bad debt and non performing loans in the books of commercial banks from 2009 up to 2014. Such a scenario impacted negatively to some closures of indigenous banks in Zimbabwe. The descriptive survey method was adopted for the study. Managerial and non-managerial employees were used as research subjects. The population of the study was on the commercial banks in Harare, Zimbabwe. The main research instruments used in the study were self- administered questionnaires. A representative sample of thirty respondents from the retail and corporate banking departmental functions and the Bankers Association of Zimbabwe was selected to participate in the study of which comprised of two opinion leaders for each commercial bank was considered. The study showed that data was collected using both primary and secondary sources. -

Monetary Policy Statement

MONETARY POLICY STATEMENT FOCUSING ON PRICE AND EXCHANGE RATE STABILITY BY JOHN P. MANGUDYA GOVERNOR RESERVE BANK OF ZIMBABWE FEBRUARY 2020 DISTRIBUTED BY VERITAS e-mail: [email protected]; website: www.veritaszim.net Veritas makes every effort to ensure the provision of reliable information, but cannot take legal responsibility for information supplied. TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND........................... 5 SECTION TWO: MONETARY POLICY MEASURES AND MPC DECISIONS .................................................................................................. 8 SECTION THREE: CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK................................. 20 ANNEXURE: .............................................................................................. 21 ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL CONDITIONS UNDERPINNING MONETARY POLICY DECISIONS ........................................................... 21 GLOBAL AND REGIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS .................... 21 International Commodity Price Developments .............................................. 23 BALANCE OF PAYMENTS DEVELOPMENTS AND OUTLOOK ............ 25 Foreign Currency Receipts ........................................................................... 26 Gold Performance ........................................................................................ 27 International Remittances ............................................................................. 28 Performance of Offshore Loans .................................................................... 29 -

Mugabe Tinashe R036260p

The impact of E-Commerce on banking sector profitability. The case of FBC Holdings Limited. By MUGABE TINASHE (R036260P) A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Business Administration Graduate School of Management Faculty of Commerce University of Zimbabwe Supervisor: Mr. A. CHIDAKWA AUGUST 2013 1 Declaration I, Tinashe Mugabe, do hereby declare that this dissertation is the result of my own investigation and research, except to the extent indicated in the acknowledgements, references and by comments included in the body of the report, and that it has not been submitted in part or in full for any other degree to any other university. ______________ Date:_________ Student signature _______________ Name: Mr. A. Chidakwa Date:_________ Supervisor’s Signature ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my beloved family members namely my beloved wife Mutsawashe Olinda Mvududu, my sons Michael and Munesuishe, Doctor Madzviti Jacob Mugabe, My mom Beatrice Mugabe, Brothers (Gabriel, Tatenda, Eugene, Simba, Jacob), The MaNcubes (Mercy and Tendai), MaNyoni (Patience), Mugabe Family, Mvududu family, Mushayi Family, relatives and MBA group members. However, it must be mentioned that coming up with this document has not been easy due to several constraints known to the researcher and close associates. iii Acknowledgement The researcher expresses heartfelt gratitude, thanks and appreciation to my beloved wife Mutsawashe Olinda Mvududu, my sons Michael and Munesuishe, Doctor Madzviti Jacob Mugabe, My mom Beatrice Mugabe, Brothers (Gabriel, Tatenda, Eugene, Simba, Jacob), The MaNcubes (Mercy and Tendai), MaNyoni (Patience), Mugabe Family, Mvududu Family, Mushayi Family, relatives, MBA colleagues, MBA group members, FBC Staff, lecturers and lastly but no least, Mr. -

Foreign Exchange Allotments Under the Foreign Exchange Auction System and Foreign Exchange Payments for the Period June 2020 to 31 May 2021

K OF AN Z B IM E B V A R B E W S E E R PRESS STATEMENT FOREIGN EXCHANGE ALLOTMENTS UNDER THE FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION SYSTEM AND FOREIGN EXCHANGE PAYMENTS FOR THE PERIOD JUNE 2020 TO 31 MAY 2021 This statement is issued in line with the Bank’s commitment to regularly keep the public informed of developments in the foreign exchange market. In terms of the foregoing, the Bank hereby publishes the following: 1. A list of the 1423 beneficiaries of US$1 235 002 234 allotted under the Main Foreign Exchange Auction; 2. A list of the 2027 beneficiaries of US$102 975 034 allotted under the SMEs Foreign Exchange Auction; and 3. A schedule showing the total foreign exchange payments amounting to US$5 469 050 131 by source, i.e. from foreign currency accounts (US$3 747 693 742), interbank market (US$383 379 121) and the Foreign Exchange Auction System (US$1 337 977 269). John P Mangudya Governor 3 June 2021 FOREIGN PAYMENTS FOR THE PERIOD JUNE 2020 TO MAY 2021 BY SOURCE OF FUNDING (US$) Foreign Currency Interbank Market Foreign Currency Month Total Accounts Payments AucƟon allotments Jun-20 316,042,558 10,776,819 26,666,279 353,485,656 Jul-20 296,548,566 32,573,666 58,934,113 388,056,345 Aug-20 289,553,476 34,144,436 67,437,280 391,135,192 Sep-20 303,978,780 28,292,721 112,952,511 445,224,012 Oct-20 354,536,979 31,755,469 112,398,745 498,691,193 Nov-20 349,670,715 23,663,747 123,228,494 496,562,956 Dec-20 373,355,186 48,615,417 125,635,566 547,606,169 Jan-21 298,114,539 24,276,155 99,600,008 421,990,702 Feb-21 455,957,451 37,049,364 144,492,215 637,499,030 Mar-21 358,331,088 52,958,997 178,876,453 590,166,538 Apr-21 216,350,754 29,558,900 128,056,464 373,966,118 May-21 135,253,650 29,713,430 159,699,141 324,666,221 Total 3,747,693,742 383,379,121 1,337,977,269 5,469,050,131 ProporƟon 69% 7% 24% 100% Foreign Exchange Auction System Allotments by Purpose for the period June 2020 to May 2021 Purpose Main AucƟon SME AucƟon Total Share (%) Raw Materials 536,576,413 25,440,940 562,017,353 42% Machinery and Equipment 216,403,917 21,834,685 238,238,602 18% Consumables (incl. -

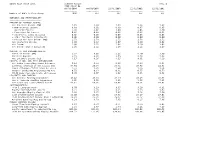

Bhcpr Peer Group Data Summary Ratios Page

BHCPR PEER GROUP DATA SUMMARY RATIOS PAGE 1 PEER GROUP 06 09/30/2004 09/30/2003 12/31/2003 12/31/2002 12/31/2001 ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- Number of BHCs in Peer Group 1000 967 967 877 826 EARNINGS AND PROFITABILITY -------------------------- PERCENT OF AVERAGE ASSETS: Net Interest Income (TE) 3.85 3.84 3.83 3.99 3.97 + Non-interest Income 0.80 0.91 0.89 0.87 0.85 - Overhead Expense 2.98 3.02 3.04 3.05 3.10 - Provision for Losses 0.16 0.21 0.22 0.26 0.24 + Securities Gains (Losses) 0.02 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.03 + Other Tax Equiv Adjustments 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 = Pretax Net Oper Income (TE) 1.52 1.59 1.52 1.59 1.51 Net Operating Income 1.09 1.12 1.07 1.10 1.02 Net Income 1.09 1.11 1.07 1.10 1.02 Net Income (Sub S Adjusted) 1.05 1.12 1.06 1.12 1.07 PERCENT OF AVG EARNING ASSETS: Interest Income (TE) 5.72 6.03 5.95 6.70 7.89 Interest Expense 1.55 1.86 1.79 2.38 3.61 Net Interest Income (TE) 4.17 4.16 4.15 4.31 4.29 LOSSES, ALLOW, AND PAST DUE+NONACCR: Net Ln&Ls Losses/Avg Loans & Leases 0.14 0.18 0.22 0.24 0.24 Earnings Coverage of Net Losses (X) 34.61 29.74 25.52 23.62 21.41 Ln&Ls Allowance/Total Loans & Leases 1.27 1.31 1.30 1.29 1.26 Nonaccr Lns&Ls+RE Acq/Lns&Ls+RE Acq 0.72 0.83 0.81 0.77 0.73 30-89 Days Past Due Loans and Leases 0.94 1.07 1.12 1.28 1.42 LIQUIDITY AND FUNDING: Net Noncore Funding Dependence 17.12 14.89 15.34 14.26 15.48 Net ST Noncore Funding Dependence 8.05 6.03 6.61 5.66 7.85 Net Loans and Leases/Total Assets 66.15 64.56 64.46 64.31 64.42 CAPITALIZATION: Tier 1 Leverage Ratio 9.50 9.29 9.35