Native Art in the Americas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marcus Amerman Resume

MARCUS J. AMERMAN PO Box 22701 Santa Fe, NM 87502 505.954.4136 Biography Marcus Amerman is an enrolled member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. He was born in Phoenix, AZ and grew up in the Pacific Northwest before settling in Santa Fe, NM. He received a BA in Fine Art at Whitman College in Walla Walla, WA and took additional art courses at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, NM. He credits the Plateau region and its wealth of talented bead artists with introducing him to the “traditional” art form of beadwork. He quickly made this art form his own, however, by creating a new genre of bead artistry in which beads are stitched down, one by one, to create realistic, pictorial images, not just large color fields or patterns. Amerman draws upon a wide range of influences to create strikingly original works that reflect his background of having lived in three different regions with strong artistic traditions, his academic introduction to pop art and social commentary and his inventive exploration of the potential artistic forms and expressions using beads. Although he is best known for his bead art, he is also a multimedia artist, painter, performance artist (his character “Buffalo Man” can be seen on the cover of the book Indian Country), fashion designer, and glass artist, as well. SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2010 — Destination X, Museum of World Culture, Göteborg, Sweden 2010 — Pop! Popular Culture in American Indian Art, Heard Museum, Phoenix, AZ 2009 — A Song for the Horse Nation, National Museum of the American Indian, New York City, NY 2009 — Looking Forward, Traver Gallery, Tacoma, WA 2009 — Pictorial Beading the Nez Perce Way, Lewis and Clark State College, Lewiston, ID 2008 — Comic Art Indigene, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Santa Fe, NM 2008 — Voices from the Mound: Contemporary Choctaw Artists Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, NM 2007 — Looking Indian (group exhibition), Untitled Artspace, Oklahoma City, OK Current Realities: A Dialogue with the People, IAO Gallery, Oklahoma City, OK 2006 — Indigenous Motivations, Natl. -

![2009–2010 Programs and Services Guide “The [Visiting Artist Experience] Has Introduced Me and My Work to Greater Possibilities](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1470/2009-2010-programs-and-services-guide-the-visiting-artist-experience-has-introduced-me-and-my-work-to-greater-possibilities-2121470.webp)

2009–2010 Programs and Services Guide “The [Visiting Artist Experience] Has Introduced Me and My Work to Greater Possibilities

2009–2010 Programs and Services Guide “The [Visiting Artist experience] has introduced me and my work to greater possibilities. Your program will have a definite impact on my practice.” —Michael Belmore (Ojibway), Visiting Artist, Native Arts Program, 2008 front cover: NMAI staff member Tony interior front cover: A student at Williams observes as Haudenosaunee the University of Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador, participants from the Native American collaborates with a Cañari community Resource Center in Rochester, New York, member in the development of a touch view objects from the museum’s collec- screen exhibit on Cañari culture. tions during a virtual museum workshop. Photo by Mark Christal Photo by Mark Christal smithsonian national museum of the american indian Programs and Services Guide 2009–2010 CONTENTS 4 Message from Kevin Gover, Director, 45 Indigenous Geography/ National Museum of the American Geografía Indígena Website Indian 45 Indigenous Geography/ Geografía Indígena Overview 5 Foreword by Carolyn McClellan, 47 Indigenous Geography/ Associate Director for Community Geografía Indígena Application and Constituent Services 49 Internships and Fellowships 6 Introduction: Programs and Services 49 Internships of the NMAI 55 Internships Application museum programs 57 Museum Stores and services (Smithsonian Enterprises) 57 Museum StoresOverview 7 Programs and Services 59 Vendor ProductProposal and Application Deadlines Questionnaire 9 Collections 61 Recruitment Program and 9 Collections Overview Visitor Services 10 Guide to Research 61 Recruitment -

Native Art, Native Voices a Resource for K–12 Learners Dear Educator: Native Art, Native Voices: a Resource for K–12 of Art

Native Art, Native Voices A Resource for K–12 Learners Dear Educator: Native Art, Native Voices: A Resource for K–12 of art. Designed for learners in grades K–12, the Learners is designed to support the integration lessons originate from James Autio (Ojibwe); Gordon of Native voices and art into your curriculum. The Coons (Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior resource includes four types of content: Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin, Chippewa/Ojibwa, Ottawa); Dyani White Hawk (Sičháŋğu Lakȟóta 1. Artist interviews [Brulé]); Marlena Myles (Spirit Lake Dakota, Mohegan, 2. Essays about artworks in Mia’s collection and Muscogee); and Margaret Swenson, a visual arts questions to support deep looking, critical educator and collaborator with Heid Erdrich (Ojibwe thinking, and discussion enrolled at Turtle Mountain) in the creation of a Native artist residency program at Kenwood Elementary 3. Art lessons developed by and with Minnesota School in Minneapolis. Native artists 4. Reading selections for students to help provide Video Interviews environmental context for the artworks. Video interviews with eight Native artists allow your This resource includes information about Native students to learn about the artists’ lives in their own cultures both past and present and supports words and to view their art and other artworks in Mia’s Minnesota state standards for visual arts and Native art galleries. View multiple segments by indi- social studies/U.S. history. vidual artists, or mix and match to consider different artists’ responses to similar questions. Each video is less than 8 minutes. Discussion questions follow the Essays & Discussion Questions videos to guide your students’ exploration of the rich Marlena Myles (Spirit Lake Dakota, Mohegan, interview content. -

INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVES on CONTEMPORARY NATIVE ART, INDIGENOUS AESTHETICS and REPRESENTATION John Paul Rangel

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Language, Literacy, and Sociocultural Studies ETDs Education ETDs 4-2-2013 INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVES ON CONTEMPORARY NATIVE ART, INDIGENOUS AESTHETICS AND REPRESENTATION John Paul Rangel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/educ_llss_etds Recommended Citation Rangel, John Paul. "INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVES ON CONTEMPORARY NATIVE ART, INDIGENOUS AESTHETICS AND REPRESENTATION." (2013). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/educ_llss_etds/37 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Education ETDs at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Language, Literacy, and Sociocultural Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i ii © 2012 Copyright by John Paul Rangel Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge Dr. Greg Cajete, my advisor and dissertation chair, for the encouragement and advice throughout the years of graduate studies. I am so grateful for his guidance, mentorship, professionalism and friendship that have had a profound impact on my understanding of Indigenous studies, education, and leadership. I also thank my committee members, Dr. Penny Pence, Dr. Anne Calhoun, and Dr. Nancy Marie Mithlo, for their valuable recommendations and insights pertaining to this study and their assistance in my professional development. To the members of the Native arts community and specifically the Native artists whose contributions to this study made it possible, I am grateful for all the conversations leading up to this project, the meals we shared and the issues you brought up. -

Dewdrop Beaded Bead. Beadwork: ON12, 24-26 Bead Four: Treasure Trove Beaded Bead

Beadwork Index through April/May 2017 Issue abbreviations: D/J =December/January FM = February/March AM = April/May JJ = June/July AS=August/September ON=October/November This index covers Beadwork magazine, and special issues of Super Beadwork. To find an article, translate the issue/year/page abbreviations (for example, “Royal duchess cuff. D10/J11, 56-58” as Beadwork, December 2011/January 2012 issue, pages 56-58.) Website = www.interweave.com or beadingdaily.com Names: the index is being corrected over time to include first names instead of initials. These corrections will happen gradually as more records are corrected. Corrections often appear in later issues of Beadwork magazine, and the index indicates these. Many corrections, including the most up-to-date ones, are also found on the website. 15th Anniversary Beaded Bead Contest Bead five: dewdrop beaded bead. Beadwork: ON12, 24-26 Bead four: treasure trove beaded bead. Beadwork: AS12, 22-24 Bead one: seeing stars. Beadwork: FM12, 18-19 Bead three: stargazer beaded bead. Beadwork: JJ12, 20-22 Bead two: cluster beaded bead. Beadwork: AM12, 20-23 Beaded bead contest winners. Beadwork: FM13, 23-25 1800s-era jewelry Georgian jewels necklace. Beadwork: D14/J15, 80-81 1900s-era jewelry Bramble necklace. Beadwork: AS13, 24-27 Royal duchess cuff. Beadwork: D10/J11, 56-58 1920s-era jewelry Art Deco bracelet. Beadwork: D13/J14, 34-37 Modern flapper necklace. Beadwork: AS16, 70-72 1950s-era jewelry Aurelia necklace. Beadwork: D10/J11, 44-47 2-hole beads. See two-hole beads 21st century designs 21st century jewelry: the best of the 500 series. -

Including Exam Week

NAS 224 Native American Beadwork Styles Winter 2016 NAS 224 - 4 credits Instructor: April E. Lindala 12 Monday meetings from 5 – 9:10 pm in Whitman 127 Office Hours: Appointments early are best. Center Native American Studies in 112 Whitman Hall CNAS Website: www.nmu.edu/nativeamericans Phone: 906-227-1397 EMAIL: [email protected] NOTE: Please put YOUR LAST NAME NAS 224 W16 in the subject line. Thank you. I will do my best to respond in a timely manner, but I will not guarantee an answer during evenings or weekends. Teaching Philosophy (Active Learning Credo) · What I hear, I forget · What I hear & see, I remember a little · What I hear, see & ask questions about or discuss with someone else, I begin to understand · What I hear, see, discuss, and do, I acquire knowledge · What I teach to another, I master Course Description: The purpose of this course is three-fold: first, study contemporary forms of cultural expression of Native bead artists; second, examine laws and cultural responsibilities associated with Native art, and third, produce a portfolio of original beadwork. Course Learning Outcomes: By the end of this course successful students will be able to… Create a portfolio of original beadwork that demonstrates mastery of multiple stitches, Reflect upon and give examples on how beadwork functions to share stories, values and ideas, Recognize federal laws in relation to Native American art and artifacts, Recognize the diversity of beadwork styles among differing Native nations, and Identify multiple Native bead artisans. Native American Studies here at NMU Mission Statement: The Center for Native American Studies offers a holistic curriculum rooted in Native American themes that . -

Native American Beadwork Part One: History, Materials, and Construction

Tech Notes, Winter 2018 Native American Beadwork Part One: History, Materials, and Construction By Nora Frankel Assistant Conservator of Objects and Textiles Beadwork is iconic in Native American art, clothing, and objects. The familiar use of glass beads dates to early European contact, building on a much longer tradition of beadwork and quillwork appliqué using materials indigenous to North America. This first of two articles on Native American beadwork will focus on history, technique, and materials in order to provide a basic understanding and context to aid in proper care and conservation of beadwork objects. Beadwork from Ancient to Modern Different culture groups have developed a unique aesthetic of colors, motifs, and styles. A design may be significant to an individual or culture, and can be a result of dreams or deep contemplation. Some patterns resonate with cultural identity or origin stories, such as triangular representations of Bear Butte in Tsitsistas (Cheyenne) beadwork, or the curvilinear Tree of Life of Haudenosaunee (Iroquois/ Six Nations) beadwork. Beadwork, like any art, evolved, borrowed, and innovated to create a rich visual history. There are many active beadworkers today, some working with traditional styles, while artists such as Jamie Okuma,1,2 and Marcus Amerman3 use traditional knowledge in a contemporary context. Many cultures have a long pre-contact tradition of beadwork using natural materials. The established use of dyed porcupine quills to decorate clothing, bags, moccasins, and other items, also paved the way for the skillful and enthusiastic use of trade beads. Quillwork techniques include sewn appliqué, wrapping, and loom work, methods later echoed in beadwork. -

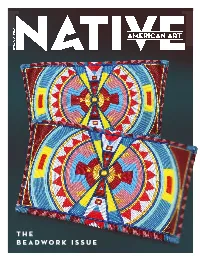

The Beadwork Issue

JUNE/JULY 2020 JUNE/JULY t h e Beadwork Issue NAA_Cover27.indd 1 5/1/20 2:59 PM Contributor John O'Hern John O’Hern retired to Santa Fe after 30 years in the museum business, specifically as the executive director and curator of the Arnot Art Museum, Elmira, New York. John was chair of the Artists Panel of the New York State Council on the Arts. He writes for gallery publications around the world, including regular monthly features on Art Market Insights in American Art Collector and Western Art Collector magazines. Paula A. Baxter Paula A. Baxter is a design historian who has worked as an art librarian, curator and adjunct professor in New York before recently moving to Scottsdale, Arizona, a long-time dream realized. The author of The Encyclopedia of Native American Jewelry, she and photographer husband Barry Katzen have just published their fourth book together, Pueblo Bead Jewelry: Living Design. Their next project she claims is “the big one.” Birdie Real Bird Birdie Real Bird, Bassannee Ahush meaning “Firsts Many Times,” is an Apsáalooke woman, leader, retired educator, historian and accomplished beader living on the Crow Reservation in South Central Montana. She learned how to bead from her grandmother decades ago. Her work has been displayed in various venues and is currently on display at the Chicago Field Museum show Apsáalooke Women and Warriors. Don Siegel Don Siegel has been a collector and dealer of historic Native art for more than 30 years. He is most interested in Apsáalooke, Crow beadwork and the history behind the art. -

Savages and Princesses Bead Hanging Craft Kit #10

Savages and Princesses Bead Hanging Craft Kit #10 INSTRUCTIONS: 1. Use the graph paper to draw out a 5x13 grid. Then use colors to plan out your design. 2. Take the plate and cut 6 notches 1/2 inch long, each 1/4 inch apart on one edge, then repeat on the other side of the plate so that the notches line up on both sides. 3. Take one piece of yarn, knot it at one end. Slide it into the frst notch (with the knot in the back) and pull it across to the corresponding notch on the other side. Loop the yarn behind and around through that notch and pull it back across to the front side. Keep doing this back and forth weaving through the notches through the last notch. Knot the end after the last notch. For more information about the artist and step-by-step instructions, visit: www.108contemporary.org/resources Use the hash tag #108CraftKits when sharing your artwork on social media! 4. Take the second piece of yarn, tie one end to the far right string on the “warp” (the vertical strings in the notches) end and thread the other through the needle. 5. Take the frst column of fve beads and thread them onto the “weft” (the horizontal thread with the needle that does the weaving), pulling them to the knot at the end. 6. Moving right to left, lay the beads on top of the ‘warp’, with a bead in each space between the strings. 7. Now moving left to right, thread the needle underneath the strings of the warp through the beads. -

September 2016 Member Appreciation!

Newsletter September 2016 Member Appreciation! Special “Members Only” Event Next Meeting: September 10, 2016 9:00 am The Point at CCYoung 4847 W Lawther Dr, Dallas, TX 75214 Dallas Bead Society Welcomes Glynna White For our September Meeting Project Our next meeting will be Saturday September 10th (second week due to holiday weekened). For this members-only event, DBS is having Glynna White, of Beadoholique Bead Shops, join us, teaching the bracelet shown. There is no charge to you (unless you would prefer to buy a bead kit from Glynna)! And… we’re providing lunch too! CLASS BEGINS AT 9:00AM!! Glynna will have 50 bead kits available, priced at $25 - $27, depending upon colorway. To help ensure that all who want a kit can get one, these will be limited to one per person until after lunch. Read on for kit colorways, supply details and important business meeting information! More September Meeting Details… Glynna’s kits (beads, rivolis, and wire only), will be available in the colorways shown. Come early to make sure you get your choice! To provide your own supplies, you’ll need: 1 foot of 12 G aluminum wire Delica Beads 2 or 3 Colors of size 11° Beads 2 or 3 Colors of size 15° Beads 2 twelve or fourteen millimeter Rivolis 75-85 2mm Glass Pearls or Fire Polished Beads 8 lb Fire Line or Nano Fil Size 11 or Smaller Needles Beading Surface Magnification Glasses Cutting Plier for Aluminum Wire (very soft wire) Needle Nose Plier We will conduct our business meeting while on lunch break. -

Native Fashion Now

Native Fashion Now Mylar dresses. Stainless-steel boas. Iridescent- leather bomber jackets with a futuristic vibe. Stunning clothes and accessories you’ll find on the runway, in museum collections, and on the street. Welcome to Native American fashion and the contemporary designers from the United States and Canada who create it! They are pushing beyond buckskin fringe and feathers to produce an impressive range of new looks. In this exhibition you’ll find the cutting edge in dialogue with the time-honored. Some Native designers work with high-tech fabric, while others favor natural materials. Innovative methods of construction blend with techniques handed down in Native communities for countless generations. Mind- bending works such as a dress made of cedar bark—a reinvention of Northwest Coast basket weaving—appear alongside T-shirts bearing controversial messages. This wearable art covers considerable ground: the long tradition of Native cultural expression, the artists’ contemporary experience and aesthetic ambition, and fashion as a multifaceted creative domain. Native Fashion Now groups designers according to four approaches we consider important. Pathbreakers have broken ground with their new visions of Native fashion. Revisitors refresh, renew, and expand on tradition, and Activators merge street wear with personal style and activism. Get ready for the Provocateurs—their conceptual experiments expand the boundaries of what fashion can be. So let’s get started! Native fashion design awaits you, ready to surprise and inspire. [signature and photo] Karen Kramer Curator of Native American and Oceanic Art and Culture The artists have loaned these works except where otherwise noted. [HOTSPOT #1] Fashion Forward Designers like Patricia Michaels are actively redefining contemporary Native fashion. -

Beadwork Index Through October/November 2018

Beadwork Index through October/November 2018 Issue abbreviations: D/J =December/January FM = February/March AM = April/May JJ = June/July AS=August/September ON=October/November This index covers Beadwork magazine, and special issues of Super Beadwork. To find an article, translate the issue/year/page abbreviations (for example, “Royal duchess cuff. D10/J11, 56-58” as Beadwork, December 2011/January 2012 issue, pages 56-58.) Website = www.interweave.com or beadingdaily.com Corrections often appear in later issues of Beadwork magazine, and the index indicates these. Many corrections, including the most up-to-date ones, are also found on the website. 15th Anniversary Beaded Bead Contest Bead five: dewdrop beaded bead. Beadwork: ON12, 24-26 Bead four: treasure trove beaded bead. Beadwork: AS12, 22-24 Bead one: seeing stars. Beadwork: FM12, 18-19 Bead three: stargazer beaded bead. Beadwork: JJ12, 20-22 Bead two: cluster beaded bead. Beadwork: AM12, 20-23 Beaded bead contest winners. Beadwork: FM13, 23-25 1800s-era jewelry Georgian jewels necklace. Beadwork: D14/J15, 80-81 1900s-era jewelry Bramble necklace. Beadwork: AS13, 24-27 Royal duchess cuff. Beadwork: D10/J11, 56-58 1920s-era jewelry Art Deco bracelet. Beadwork: D13/J14, 34-37 Modern flapper necklace. Beadwork: AS16, 70-72 1950s-era jewelry Aurelia necklace. Beadwork: D10/J11, 44-47 2-hole beads. See two-hole beads 20th anniversary of Beadwork Beadwork celebrates 20 years of publication. Beadwork: ON17, 10-13 21st century designs 21st century jewelry: the best of the 500 series. Beadwork: AM12, 18 3-D block motifs Cosmo cuff. Beadwork: AM13, 60-62 Tumbling blocks.