Reserve Positions in the 3Rd Canadian Infantry Division During the Battle of Normandy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pioneer Battalions

Guide to Sources Relating to Units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force Pioneer Battalions Pioneer Battalions Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 1st Canadian Pioneer Battalion .................................................................................................................. 2 2nd Canadian Pioneer Battalion ................................................................................................................. 5 3rd Canadian Pioneer Battalion ............................................................................................................... 22 4th Canadian Pioneer Battalion (formerly 67th Battalion) ....................................................................... 27 4th Canadian Pioneer Battalion ............................................................................................................... 29 5th Canadian Pioneer Battalion ............................................................................................................... 31 Follow the references for these Pioneer Battalions: 48th Pioneer Battalion, see 48th Infantry Battalion 67th Pioneer Battalion, see 67th Infantry Battalion 107th Pioneer Battalion, see 107th Infantry Battalion 123rd Pioneer Battalion, see 123rd Infantry Battalion 124th Pioneer Battalion, see 124th Infantry Battalion Guide to Sources Relating to Units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force Pioneer Battalions Introduction Worked -

Canadian Fatal Casualties on D-Day

Canadian Fatal Casualties on D-Day (381 total) Data from a search of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website, filtered by date (6 June 1944) and eliminating those in units that did not see action on the day Key: R.C.I.C = Royal Canadian Infantry Corps; R.C.A.C. = Royal Canadian Armoured Corps; Sqdn. = Squadron; Coy. = Company; Regt. = Regiment; Armd. = Armoured; Amb. = Ambulance; Bn. = Battalion; Div. = Division; Bde. = Brigade; Sigs. = Signals; M.G. = Machine Gun; R.A.F. = Royal Air Force; Bty. = Battery Last Name First Name Age Rank Regiment Unit/ship/squadron Service No. Cemetery/memorial Country Additional information ADAMS MAXWELL GILDER 21 Sapper Royal Canadian Engineers 6 Field Coy. 'B/67717' BENY-SUR-MER CANADIAN WAR CEMETERY, REVIERS France Son of Thomas R. and Effie M. Adams, of Toronto, Ontario. ADAMS LLOYD Lieutenant 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, R.C.I.C. RANVILLE WAR CEMETERY France ADAMSON RUSSEL KENNETH 19 Rifleman Queen's Own Rifles of Canada, R.C.I.C. 'B/138767' BENY-SUR-MER CANADIAN WAR CEMETERY, REVIERS France Son of William and Marjorie Adamson, of Midland, Ontario. ALLMAN LEONARD RALPH 24 Flying Officer Royal Canadian Air Force 440 Sqdn. 'J/13588' BENY-SUR-MER CANADIAN WAR CEMETERY, REVIERS France Son of Ephraim and Annie Allman; husband of Regina Mary-Ann Allman, of Schenectady, New York State, U.S.A. AMOS HONORE Private Le Regiment de la Chaudiere, R.C.I.C. 'E/10549' BENY-SUR-MER CANADIAN WAR CEMETERY, REVIERS France ANDERSON JAMES K. 24 Flying Officer Royal Canadian Air Force 196 (R.A.F.) Sqdn. -

KAVANAUGH Gordon Henry

Gordon Henry KAVANAUGH Rifleman Royal Winnipeg Rifles M-8420 M-8420 Gordon Henry KAVANAUGH Personel information: Gordon Henry KAVANAUGH was born 22 December 1924 in Biggar, Saskatchewan, Canada. From the 'Soldiers Service Book' it appears that on 22 November 1943 the family KAVANAUGH was made up of father and mother, John Henry and Odile Susan, and Gordon's two sisters, Verna May and Tresa. Verna May was also in military service and as Lance Corporal, worked in the Canadian Women's Army Corps (CWAC) 103 Depot Company in Kingston, Ontario. Tresa was married to Joe Clarke. Tresa was married to Joe Clarke. Together they had four children, Kenneth aged 16, Patricia 14, Loren 12 and Michial 18 months. Tresa lived with her family in Fairfax, Alberta where they ran a farm. Gordon Henry attended the St Alphonsus Separate School and was brought up as a Roman Catholic. St. Alphonsus Separate School 1915 corner Parkstreet en Pellisser street He lived at different addresses; from his birth until he was four, in Biggar, Saskatchewan. Then the family moved to 506 Janette Avenue, Windsor, Ontario, only a short distance from the US border and Detroit. Gordon lived for a year here and after that for eight years in Toledo, Ohio, USA. Until he entered army service in 1942, Gordon lived with his sister Tresa and worked on the farm in Fairfax, Alberta. While there he also worked for about a month with the firm W.Evans as a truck driver. Gordon Henry Kavanaugh was not married and it is not known if he had a girlfriend. -

8 Th Newsletter

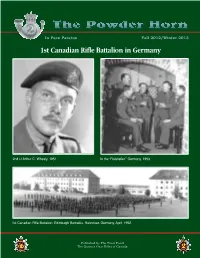

In Pace Paratus Fall 2012/Winter 2013 1st Canadian Rifle Battalion in Germany 2nd Lt Arthur C. Whealy, 1951 In the “Ratskeller,” Germany, 1953 1st Canadian Rifle Battalion, Edinburgh Barracks, Hannover, Germany, April, 1952. Published by The Trust Fund The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada 61 years ago 1st Canadian Rifle Bn sailed to Germany It has been 61 years since the 1st Canadian Rifle sonnel from rifles, line infantry or highland militia regi- Battalion sailed for foreign shores and NATO service in ments. As an independent brigade, in addition to the Germany and The Honourable Arthur C. Whealy, who infantry regiments, its complement included an died recently, was the last of eight officers from The armoured squadron, an artillery troop and contingents Queenʼs Own Rifles of Canadaʼs 1st (Reserve) Battalion from supporting services. Brigade commander was Brig who had volunteered to join the new battalion when it Geoffrey Walsh, DSO, who had served in Sicily and was formed. 57 other ranks from the reserve unit also Italy in World War Two and was awarded the joined, along with 120 new recruits. Following its forma- Distinguished Service Order for “Gallant and tion the battalion mustered at Camp Valcartier, QC, for Distinguished Services” in Sicily. six months training. In October, 1CRB paraded to the Plains of Abraham where it was inspected by Princess Upon arrival in Hannover, 1CRB and 1CHB were quar- Elizabeth during the first major tour of Canada by tered in a former German artillery housing now Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh, one renamed Edinburgh Barracks. -

The Normandy Campaign About:Reader?Url=

The Normandy Campaign about:reader?url=https://www.junobeach.org/canada-in-wwii/article ... junobeach.org The Normandy Campaign 22-27 minute s Canada in the Second World War The Normandy Campaign Extending the Bridgehead, June 7th - July 4th, 1944 Personnel of the Royal Canadian Artillery with a 17-pounder anti tank gun in Normandy, 22 June 1944. Photo by Ken Bell. Department of National Defence I National Archives of Canada, PA- 169273. The day following the Normandy landing, the 9th Infantry Brigade led the march towards Carpiquet where an airfield had been designated as the objective. The North Nova Scotia Highlanders, supported by the 27th Armoured Regiment (Sherbrooke Fusiliers) captured the village of Buron but a few kilometres further south ran into a German counter-offensive. The Canadians were facing the 12th SS Panzer Division (Hitlerjugend), a unit of young - mostly 18- year olds - but fanatical soldiers. The North Nova Scotia Highlanders put up a fierce fight but were finally forced to pull back. Near Authie, a neighbouring village, black smoke rose in column from the burning debris of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers' tanks, decimated by the German Panthers. rThe enemy then engaged our fire from BURON with 75, 88s, 1 of 12 2021-03-02, 4:13 p.m. The Normandy Campaign about:reader?url=https://www.junobeach.org/canada-in-wwii/article ... mortars and everything they had. Under this fire enemy infantry advanced and penetrated the forward slit trenches of D Company. It was impossible to stop them ... North Nova Scotia Highlanders, War Dia[Y. 7 June 1944 During the next couple of days, Canadians could hardly move without meeting with stubborn resistance from German divisions. -

Atscaf Mai 2011

n° 05 – Mai 2011 CCaallvvaaddooss PPRROOCCHHAAIINNEESS MMAANNIIFFEESSTTAATTIIOONNSS –– DDAATTEESS AA RREETTEENNIIRR • Mardi 3 mai ; Dernier délai pour la commande de vins de Touraine. • Samedi 7 mai : Soirée cabaret à Dives sur Mer. • Vendredi 27 et samedi 28 mai : Coupe de Normandie à Forges les Eaux (76) • Samedi 2 juillet ; Visite du parc de Thoiry (information dans ce bulletin) Flash Info : Il reste quelques places disponibles pour le voyage en Inde du Sud prévu du 17 au 28 novembre prochain ; bulletin d’inscription en fin de ce bulletin ; renseignements en contactant directement Yvonne Génin au 02.31.26.73.38. Le secrétariat sera fermé du 2 au 6 mai inclus Coupe de Normandie à Forges les Eaux les 27 et 28 mai 2011 Si vous voulez de nouveau savourer les joies de la victoire et de la convivialité qui règnent lors de ces manifestations, nous vous invitons à vous manifester dès maintenant pour passer deux journées de détente à Forges les Eaux. Compétiteurs et supporters inscrivez-vous dès maintenant auprès de votre responsable sportif ou si vous êtes simple supporter, directement auprès de Ph. Deslandes pour obtenir le programme et le tarif des prestations proposées. En dehors de la compétition sportive, des activités ludiques sont prévues : tournoi de scrabble, visite d’un musée et d’une faïencerie. La région est magnifique et le VVF qui nous accueille est très agréable. Nous faisons donc entière confiance à l’ATSCAF de Rouen, responsable de l’organisation, pour que ce Souvenirs 2009 !... week end soit une réussite. Venez nombreux, vous ne le regretterez pas. PS : Nous recherchons parmi les concurrents du tennis de table, foot ou pétanque 4 à 6 volontaires pour disputer le tournoi de volley qui se déroulera dans l’après midi après le tournoi de foot. -

Canadian Infantry Combat Training During the Second World War

SHARPENING THE SABRE: CANADIAN INFANTRY COMBAT TRAINING DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By R. DANIEL PELLERIN BBA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2007 BA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2008 MA, University of Waterloo, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History University of Ottawa Ottawa, Ontario, Canada © Raymond Daniel Ryan Pellerin, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT “Sharpening the Sabre: Canadian Infantry Combat Training during the Second World War” Author: R. Daniel Pellerin Supervisor: Serge Marc Durflinger 2016 During the Second World War, training was the Canadian Army’s longest sustained activity. Aside from isolated engagements at Hong Kong and Dieppe, the Canadians did not fight in a protracted campaign until the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The years that Canadian infantry units spent training in the United Kingdom were formative in the history of the Canadian Army. Despite what much of the historical literature has suggested, training succeeded in making the Canadian infantry capable of succeeding in battle against German forces. Canadian infantry training showed a definite progression towards professionalism and away from a pervasive prewar mentality that the infantry was a largely unskilled arm and that training infantrymen did not require special expertise. From 1939 to 1941, Canadian infantry training suffered from problems ranging from equipment shortages to poor senior leadership. In late 1941, the Canadians were introduced to a new method of training called “battle drill,” which broke tactical manoeuvres into simple movements, encouraged initiative among junior leaders, and greatly boosted the men’s morale. -

Of the 2Nd Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles, Canadian Expeditionary Force, Is Interred in Mazingarbe Communal Cemetery Extension: Grave Reference, III

Private Joseph Robert Barrett (Number 261054) of the 2nd Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles, Canadian Expeditionary Force, is interred in Mazingarbe Communal Cemetery Extension: Grave reference, III. A. 15. His occupation prior to service recorded as that of a telegraph operator working at International Falls, Massachusetts, John Robert Barrett had sailed from Newfoundland to Vanceboro, Maine, likely on board the vessel SS Glencoe – Bruce and Sylvia(?) are other ships also noted – in March of 1903 to live with a sister at 604, Western Avenue, Lynn, Massachusetts, while taking up employment there. 1 (Previous page: The image of the 2nd Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles, shoulder-flash is from the Wikipedia Web-Site.) The date on which he re-crossed the United States-Canadian border in order to enlist does not appear in his personal files; however, Joseph Robert Barrett did so at Fort Frances, Ontario – just across the Rainy River from where he was working, so it may be that he crossed on the day that he enlisted – on March 21 of 1916, signing on for the duration of the war at the daily rate of $1.10. He also passed a medical examination and was attested on that same day. Private Barrett is documented as having been attached upon his enlistment into the 212th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and officially recorded as a soldier of that unit by its Commanding Officer on March 27. Not quite three weeks afterwards, on May 15 or 16, he was transferred into the 97th Battalion (American Legion), also of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. -

Recueil Des Actes Administratifs Spécial N°14-2020-094

RECUEIL DES ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS SPÉCIAL N°14-2020-094 CALVADOS PUBLIÉ LE 17 JUILLET 2020 1 Sommaire Direction départementale de la cohésion sociale 14-2020-06-13-001 - Liste des admis au BNSSA (1 page) Page 3 Direction départementale des territoires et de la mer du Calvados 14-2020-07-17-001 - Arrêté préfectoral portant agrément de la Société des Eaux de Trouville Deauville et Normandie pour la réalisation des opérations de vidange, transport et élimination des matières extraites des installations d'assainissement non collectif (4 pages) Page 5 14-2020-07-16-005 - Arrêté préfectoral prescrivant la restauration de la continuité écologique au point de diffluence de la rivière Orbiquet et du ruisseau Graindin et sur la rivière Orbiquet au droit du vannage du Carmel, commune de LISIEUX (5 pages) Page 10 Préfecture du Calvados 14-2020-07-17-002 - 20200717-ArrêtéGrandsElecteurs (1 page) Page 16 14-2020-07-17-003 - 20200717-GRANDS ELECTEURS (48 pages) Page 18 14-2020-07-17-004 - Arrêté préfectoral du 17 juillet 2020 portant réglementation de la circulation sur les autoroutes A13 et A132 (4 pages) Page 67 2 Direction départementale de la cohésion sociale 14-2020-06-13-001 Liste des admis au BNSSA Jury du 13 juin 2020 Direction départementale de la cohésion sociale - 14-2020-06-13-001 - Liste des admis au BNSSA 3 Direction départementale de la cohésion sociale - 14-2020-06-13-001 - Liste des admis au BNSSA 4 Direction départementale des territoires et de la mer du Calvados 14-2020-07-17-001 Arrêté préfectoral portant agrément de la Société des -

La Lettre De Cairon

La lettre de Cairon BULLETIN D’INFORMATIONS MUNICIPALES N° 89 SEPTEMBRE 2018 TELEPHONE : 02 31 80 01 33 – TELECOPIE : 02 31 80 65 48 Courriel : [email protected] – site web : www.cairon.info Le Mot du Maire Sommaire Le mot du maire 1 Madame, Monsieur, L’école de Cairon 2 L’Espace Jeunes 2 Dans le précédent bulletin d’informations municipales de Aménagement de la place des commerces 2 début juin je vous indiquais que les élus de Cairon et de Le salon « Sympa’tifs » 2 Rosel envisageaient la fusion de leurs deux communes à la Environnement 3 fin de l’année 2018. Des groupes de travail avaient été Le CLIC de Caen Ouest 4 constitués et le projet global devait être présenté à la APAEI 4 population le 18 juin en réunion publique avant une La chiffo 4 délibération par les conseils municipaux le 5 juillet. Le repas des ainés 4 Une très grande majorité des élus de Cairon était favorable La bibliothèque 5 aux conclusions des travaux des commissions. Le club des ainés 6 Malheureusement, avant même qu’ils ne délibèrent, de 24 ième édition des foulées de la Mue 6 nombreux élus de Rosel ont indiqué qu’ils ne voteraient pas Expo photo du CLIC 6 le projet qui avait été élaboré. Dans ces conditions, face à La saison culturelle aux Tilleuls 7,8 un projet qui ne recueillait pas l’assentiment de la très 17 ième journée de l’amitié avec Bébéquilts 8 grande majorité des élus, il ne nous était pas possible de Le yoga ici ou là-bas 9 poursuivre dans le processus de fusion et la réunion Sophravous 9 publique a été annulée. -

Flexo Mode D'emploi

BUS DE SOIRÉE Lignes Flexo, les vendredis et samedis soirs, toute l’année. Départs de Tour Leroy à 22h30 et 0h30. Pour vos retours du centre ville les vendredis et samedis soirs, pensez à la ligne Flexo 1. Flexo mode d’emploi Un seul et unique point de montée : Tour Leroy à 22h30 et 0h30. A votre montée dans le bus Flexo 1, indiquez au conducteur l’arrêt où vous souhaitez descendre. Tous les arrêts de la zone ne sont pas systématiquement desservis : l’itinéraire est défini en fonction des voyageurs à bord. Service accessible aux tarifs Twisto. Communes desservies : Flexo Authie, Cambes en Plaine, Mathieu, St-Contest, St-Germain-la-Blanche-Herbe, Point de Villons les Buissons. montée unique. Départs à 22h30 et 0h30 1 les vendredis et samedis soirs. BUS DE SOIRÉE Lignes Flexo, les vendredis et samedis soirs, toute l’année. Départs de Tour Leroy à 22h30 et 0h30. Pour vos retours du centre ville les vendredis et samedis soirs, pensez à la ligne Flexo 2. Flexo mode d’emploi Un seul et unique point de montée : Tour Leroy à 22h30 et 0h30. A votre montée dans le bus Flexo 2, indiquez au conducteur l’arrêt où vous souhaitez descendre. Tous les arrêts de la zone ne sont pas systématiquement desservis : l’itinéraire est défini en fonction des voyageurs à bord. Service accessible aux tarifs Twisto. Communes desservies : Flexo Biéville Beuville, Blainville sur Orne, Epron, Point de Hérouville St-Clair, montée unique. Periers sur le Dan. Départs à 22h30 et 0h30 les vendredis et 2 samedis soirs. -

Signal Service, Canadian Engineers

Guide to Sources Relating to Units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force Signal Service, Canadian Engineers Signal Service, Canadian Engineers Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Canadian Corps Signal Company ............................................................................................................... 2 1st Canadian Divisional Signal Company, Canadian Engineers .................................................................. 4 2nd Canadian Divisional Signal Company, C.E. ........................................................................................... 7 3rd Canadian Divisional Signal Company, C.E. ......................................................................................... 13 3rd Canadian Divisional Signal Company, C.E. ......................................................................................... 15 4th Canadian Divisional Signal Company, C.E. ......................................................................................... 16 4th Canadian Divisional Signal Company, C.E. ......................................................................................... 17 5th Canadian Divisional Signal Company, C.E. ......................................................................................... 20 6th Canadian Divisional Signal Company, C.E. ......................................................................................... 21 Cable Section ..........................................................................................................................................