Public Industrial Enterprises July 1986

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bilingual / Bi-Annual Pakistan Studies, English / Urdu Research Journal

I ISSN: 2311-6803 PAKISTAN STUDIES Bilingual / Bi-annual Pakistan Studies, English / Urdu Research Journal Vol. 03 Serial No. 1 January - June 2016 Editor: Dr.Mohammad Usman Tobawal PAKISTAN STUDY CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN, QUETTA. II III MANAGING COMMITTE Patron Prof. Dr. Javaid Iqbal Vice Chancellor Editor Inchief Prof. Dr. Naheed Anjum Chishti Editor Dr. Muhammad Usman Tobawal Assistant Editors Dr. Noor Ahmed Prof. Dr. Kalimullah Prof. Dr. Ain ud Din Prof. Ghulam Farooq Baloch Prof. Yousuf Ali Rodeni Prof. Surriya Bano Associate Editors Prof. Taleem Badshah Mr. Qari Abdul Rehman Miss. Shazia Jaffar Mr. Nazir Ahmed Miss. Sharaf Bibi Composing Section Mr. Manzoor Ahmed Mr. Bijar Khan Mr. Pervaiz Ahmed IV EDITORIAL BOARD INTERNATIONAL Dr. Yanee Srimanee, Ministry of Commerce, Thailand. Prof. M. Aslam Syed Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Dr. Jamil Farooqui Dept. of Sociology and Anthropology, International Islamic University, Kaula Lumpur Prof. Dr. Shinaz Jindani, Savannah State University of Georgia, USA Dr. Elina Bashir, University of Chicago. Dr. Murayama Kazuyuki, #26-106, Hamahata 5-10, Adachi-ku, Tokyo 1210061, Japan. Prof. Dr. Fida Muhammad, State University of New York Oneonta NY 12820 Dr. Naseer Dashti, 11 Sparows Lane, New Elthaw London, England SEQ2BP. Dr. Naseeb Ullah, International Correspondent, Editor & Political Consultant, The Montreal Tribune, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Johnny Cheung Institute of Culture & Language Paris, France. V EDITORIAL BOARD NATIONAL Prof. Dr.Abdul Razzaq Sabir, Vice Chancellor, Turbat University. Dr. Fakhr-ul-Islam University of Peshawar. Dr. Abdul Saboor Pro Vice Chancellor, University of Turbat. Syed Minhaj ul Hassan, University of Peshawar. Prof. Dr. Javaid Haider Syed, Gujrat University. -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2008 the Management Team Is Also Being Trained on Various Basel II Requirements

Contents Corporate Information......................................................................01 Director’s Report to the Shareholders........................................02 Statement of Compliance with the Code of Corporate Governance.......................................................07 Statement of Internal Control........................................................09 Notice of Annual General Meeting...........................................10 Review Report to the Members on Statement of the Compliance with Best Practices of Code of Corporate Governance...................................................................12 Auditor’s Report to Members.......................................................13 Balance Sheet......................................................................................15 Profit and Loss Account..................................................................16 Cash Flow Statement.......................................................................17 Statement Of Changes In Equity................................................18 Notes to Financial Statements.....................................................19 Six Years Key financial Data...........................................................62 Annexure - 1.........................................................................................63 Combined Pattern of CDC and Physical Share Holdings...................................................................64 Combined Pattern of CDC and Physical Share Holdings ..................................................................65 -

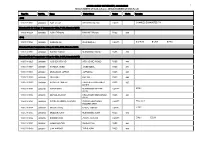

List of Category -I Members Registered in Membership Drive-Ii

LIST OF CATEGORY -I MEMBERS REGISTERED IN MEMBERSHIP DRIVE-II MEMBERSHIP CGN QUOTA CATEGORY NAME DOB BPS CNIC DESIGNATION PARENT OFFICE DATE MR. DAUD AHMAD OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT COMPANY 36772 AUTONOMOUS I 25-May-15 BUTT 01-Apr-56 20 3520279770503 MANAGER LIMITD MR. MUHAMMAD 38295 AUTONOMOUS I 26-Feb-16 SAGHIR 01-Apr-56 20 6110156993503 MANAGER SOP OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT CO LTD MR. MALIK 30647 AUTONOMOUS I 22-Jan-16 MUHAMMAD RAEES 01-Apr-57 20 3740518930267 DEPUTY CHIEF MANAGER DESTO DY CHEIF ENGINEER CO- PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 7543 AUTONOMOUS I 17-Apr-15 MR. SHAUKAT ALI 01-Apr-57 20 6110119081647 ORDINATOR COMMISSION 37349 AUTONOMOUS I 29-Jan-16 MR. ZAFAR IQBAL 01-Apr-58 20 3520222355873 ADD DIREC GENERAL WAPDA MR. MUHAMMA JAVED PAKISTAN BORDCASTING CORPORATION 88713 AUTONOMOUS I 14-Apr-17 KHAN JADOON 01-Apr-59 20 611011917875 CONTRALLER NCAC ISLAMABAD MR. SAIF UR REHMAN 3032 AUTONOMOUS I 07-Jul-15 KHAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110170172167 DIRECTOR GENRAL OVERS PAKISTAN FOUNDATION MR. MUHAMMAD 83637 AUTONOMOUS I 13-May-16 MASOOD UL HASAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110163877113 CHIEF SCIENTIST PROFESSOR PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISION 60681 AUTONOMOUS I 08-Jun-15 MR. LIAQAT ALI DOLLA 01-Apr-59 20 3520225951143 ADDITIONAL REGISTRAR SECURITY EXCHENGE COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD CHIEF ENGINEER / PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 41706 AUTONOMOUS I 01-Feb-16 LATIF 01-Apr-59 21 6110120193443 DERECTOR TRAINING COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD 43584 AUTONOMOUS I 16-Jun-15 JAVED 01-Apr-59 20 3820112585605 DEPUTY CHIEF ENGINEER PAEC WASO MR. SAGHIR UL 36453 AUTONOMOUS I 23-May-15 HASSAN KHAN 01-Apr-59 21 3520227479165 SENOR GENERAL MANAGER M/O PETROLEUM ISLAMABAD MR. -

Details of Unclaimed Insurance Benefits As at June 30, 2019

DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED INSURANCE BENEFITS AS AT JUNE 30, 2019 S.NO NAME 1 Iftikhar Rafiq 2 Mudasar Zawar 3 Hamid Ali Khan 4 Muhammad Waseem 5 Aatif Maqsood 6 Azhar Hussain 7 Syed Fasih Uddin 8 Shameer Ali 9 M. Irfan Siddiqui 10 Abdul Hai 11 Abdul Qayum 12 Abdul Qayum 13 Nasreen Kausar 14 Muhammad Naeem 15 Muhammad Abdullah Tufail Khan 16 Nabila Sarwar 17 Tahir Abbas Kazmi 18 Saiqa Imtiaz Arif 19 Dr. Shazia Javed 20 Aman Ullah Tahir 21 Afzal Ahmed 22 Iqbal Hussain Shaikh S/O Bhoonger Shaikh 23 Iqbal Hussain Lakho S/O Ghulam Hussain Lakho 24 Muhammad Darvesh Lakhan S/O Ahmed Din Lakhan 25 Samreen Ahmed 26 Muhammad Shoukat 27 Saeed Ahmed 28 Muhammad Ijaz 29 Khalid Mahmood 30 Kamal Khan Laghri 31 Haleema Bibi 32 Faisal Aziz 33 Jamila Ali D/O Ali Muhammad Qureshi 34 Manzoor Ahmed Khokar 35 Faisal Cheema 36 Mohammad Ali DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED INSURANCE BENEFITS AS AT JUNE 30, 2019 S.NO NAME 37 Mazher Mohib 38 Zahid Mehmood 39 Naushad 40 Gulzar Hussain S/O Abdul Lateef 41 Iqbal Khanani S/O Muhammad 42 Iqbal Khanani S/O Muhammad 43 Bhagyou S/O Thado 44 Malik Nasrullah Jan S/O Malik Muhammad Ikram 45 Seema Jabeen W/O Shakeel Khan 46 Farah Zeba D/O Muhammad Hussain 47 Imran Ilyas Jutt S/O Mohammad Ilyas Jutt 48 Eagle Maritime Services 49 Shah Sikander S/O Sarwar Khan 50 Anwar Mohammad Ali S/O Hassain Mohammad Ali Ghulam 51 Nighat Kanwal Pervez W/O Pervez Ali Khan 52 Mohammad Khalid Alvi S/O Mohammad Iqbal Alvi 53 Muhammad Jandad S/O Fazal Dad 54 Nasir Khan S/O Ajmal Khan 55 Abdul Hameed S/O Muhammad Saddique 56 Ameer Hamza S/O Rehm Din 57 Shoaib Ali -

JHELUM-Ren8c3.Pdf

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE NAME BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 47418 SHAMREZ SAJJAD SAJJAD AHMED MARKAZI JAMIA MASJID SOHAWA DISTT,, 15-3-1981 MATRIC 29/02/2015 JHELUM, PUNJAB 2 40771 IKHLAQ AHMED FAQIR ISLAM PURA TEH, DINA DISTT. JHELUM , 24-2-1982 MATRIC 11/7/2014 MUHAMMAD JHELUM, PUNJAB 3 31608 MUHAMMAD YAQUB DAULAT ALI VILL & P/O BEHLOLA VIA KALA GUJRAN TEH & 4-9-1963 MATRIC 11/07/2014 DISTT. JHELUM , JHELUM, PUNJAB 4 21324 ILYAS AHMED ARJASAB KHAN V.P.O. SAHAL VIA BARAGOWAHTEH SOHAWA 1/8/1959 MATRIC 13/07/2014 DIST, JHELUM, PUNJAB 5 22038 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD H.B-230MOH MAJAHID ABAD, JHELUM, PUNJAB 5/2/1959 F.A 14/07/2014 KHAWAR MAHMOOD KHAN 6 30123 ABDUL MAJEED HAFIZ GHULAM VILL KANTRILLA VIA KAL GUJRAN DISTT, 12-12- MATRIC 15/07/2014 RASUL JHELUM , JHELUM, PUNJAB 1961 7 27020 MEHWISH TAJ TAJ MUHAMMAD D-288, BILAL TOWN, JHELUM, PUNJAB 7-3-1982 MATRIC 16/07/2014 8 25314 SHABBIR HUSSAIN MUHD. SIDDIQ NEW MOH. G.T. ROAD. DINA., JHELUM, PUNJAB 6/6/1958 MATRIC 18/07/2014 SHAH SHAH 9 37458 NISHAT JAVEED SULTAN THATHI GUJRAN P/O KASHMIR COLONY TEH, & 10-5-1973 MATRIC 9/8/2014 MEHMOOD DISTT, JHELUM, JHELUM, PUNJAB 10 35342 MUHAMMAD IQBAL MAIN SAKHI VILLAGE & P.O. SANGHOL,JHELUM., JHELUM, 10/11/1941 B.Sc. 27/8/2014 MIRZA MUHAMMAD PUNJAB 11 22077 MUHAMMAD AMIN MUHAMMAD VILL. SHEIKHA UBE-E-DRYAP.O. CHAK DOULAT, 20/5/1976 MATRIC 03/09/2014 AKBAR JHELUM, PUNJAB 12 37009 RAHAT KAYANI MUHAMMAD VILLAGE AND P/O BARAGOWAH TEH, SOHAWA 11-3-1981 MATRIC 7/9/2014 ZULFIQAR DISTT, , JHELUM, PUNJAB 13 22160 ADNAN WAHEED ALLAH DITTA V.P.O. -

S. No. Folio No. Security Holder Name Father's/Husband's Name Address

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders without / invalid CNIC # as of 31-12-2019 S. Folio No. Security Holder Name Father's/Husband's Name Address No. of No. Securities 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN S/O MR. MOHAMMAD WAZIR KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI S/O MR. MOHD ABDUL HAFEEZ 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3,280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN S/O MURTUZA MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD MR. HAMID HUSSAIN C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE S/O A. RAHIM B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9,382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED S/O GHULAM QADDIR KHAN H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN S/O MOHD NASRULLAH KHAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA S/O FAZAL-I-MAHMOOD 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1,919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN S/O ABDUR REHMAN KHAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8,530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN SARDAR M. FAROOQ IBRAHIM 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5,945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN S/O KH. -

Unclaimed Deposit 2014

Details of the Branch DETAILS OF THE DEPOSITOR/BENEFICIARIYOF THE INSTRUMANT NAME AND ADDRESS OF DEPOSITORS DETAILS OF THE ACCOUNT DETAILS OF THE INSTRUMENT Transaction Federal/P rovincial Last date of Name of Province (FED/PR deposit or in which account Instrume O) Rate Account Type Currency Rate FCS Rate of withdrawal opened/instrume Name of the nt Type In case of applied Amount Eqv.PKR Nature of Deposit ( e.g Current, (USD,EUR,G Type Contract PKR (DD-MON- Code Name nt payable CNIC No/ Passport No Name Address Account Number applicant/ (DD,PO, Instrument NO Date of issue instrumen date Outstandi surrender (LCY,UFZ,FZ) Saving, Fixed BP,AED,JPY, (MTM,FC No (if conversio YYYY) Purchaser FDD,TDR t (DD-MON- ng ed or any other) CHF) SR) any) n , CO) favouring YYYY) the Governm ent 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 PRIX 1 Main Branch Lahore PB Dir.Livestock Quetta MULTAN ROAD, LAHORE. 54500 LCY 02011425198 CD-MISC PHARMACEUTICA TDR 0000000189 06-Jun-04 PKR 500 12-Dec-04 M/S 1 Main Branch Lahore PB MOHAMMAD YUSUF / 1057-01 LCY CD-MISC PKR 34000 22-Mar-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/S BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/SLAHORE LCY 2011423493 CURR PKR 1184.74 10-Apr-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR LCY 2011426340 CURR PKR 156 04-Jan-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING IND HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING INDSTREET NO.3LAHORE LCY 2011431603 CURR PKR 2764.85 30-Dec-04 "WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/SSUNSET LANE 1 Main Branch Lahore PB WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/S LCY 2011455219 CURR PKR 75 19-Mar-04 NO.4,PHASE 11 EXTENTION D.H.A KARACHI " "BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD.FEROZE PUR 1 Main Branch Lahore PB 0301754-7 BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD. -

DAM Collection 20180912.Xlsx

PM & CJP FUND FOR DIAMER BHASHA AND MOHMAND DAM ACCOUNT LIST OF DONOR FOR 12 SEP-18 RECEIPT Bank Depositor Name Amount AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD YUSUF 0117 132,013.20 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD NASREEN SADIQ 0117 50,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD FARHAN KHAN 0117 31,600.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD NAZIR 0117 30,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD JAHANZEB 0117 10,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ADC 0117 6,059.56 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD EJAZ UL HASAN 0117 5,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SARWAT SALMAN 0117 5,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD NOMAN IFTIKHAR 0117 5,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD MUHAMMAD MAZHAR 0117 5,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD M AZMA RASHEED 0117 5,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD YUSUF HUSSAIN 0117 4,500.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD FAIROZA FAIZA 0117 3,100.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD HAKIM 0117 3,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ALI SHER 0117 1,510.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ASIF MALIK 0117 1,500.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ADC 0117 1,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD OSAMA SHAH 0117 1,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD GHULAM HUSSAIN 0117 1,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD JAFAR 0117 1,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD MUZAFFAR AHMED 0117 1,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD M ASHFAQ 0117 1,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD UMER TARIQ 0117 1,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ADNAN 0117 1,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD KAMRAN SHAH 0117 1,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD GULZAR 0117 1,000.00 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) -

1 Saif Ullah Compt. Chances Exhausted P-1 110021710002 Shereen Hazrat Asma Farooq Pass 130061810001 Rana M Farooq Naqash Ali

1 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc/B.Com. ANNUAL EXAMINATION 2020 (Part-II) Reg. No. Roll No. Name Father Name Status Marks Remarks (002) 110021710002 2010001 SAIF ULLAH SHEREEN HAZRAT COMPT. CHANCES EXHAUSTED P-1 Islamabad Model College of Commerce for Girls, F-10/3, Islamabad (006) 130061810001 2010002 ASMA FAROOQ RANA M FAROOQ PASS 820 (001) 130011710168 2010003 NAQASH ALI ZULFIQAR ALI COMPT. B-C-R-W B-LAW B-TAX Islamabad Model Postgraduate College for Girls, F-7/2, Islamabad (003) 110031810082 2010004 KASHAF NAWAZ MUHAMMAD NAWAZ PASS 433 Islamabad Model Postgraduate College for Girls, G-10/4, Islamabad (005) 110051810025 2010005 ALISHBA ARSHAD ARSHAD MEHMOOD PASS 446 110051810097 2010006 KHADIJA JAVED JAVED IQBAL PASS 491 110051810098 2010007 MUQADDAS JAFFAR JAFFAR ALI PASS 501 110051810099 2010008 IQRA WALI RAJ WALI PASS 480 110051810100 2010009 AFSHEEN ZAHEER ZAHEER-UD-DIN-BABER PASS 427 BHATTI 110051810101 2010010 HADIA KHAN MUHAMMAD ASHRAF COMPT. EDU:II KHAN 110051810102 2010011 MAHAM AYUB CH CHAUDHARY MUHAMMAD PASS 481 AYUB 110051810103 2010012 SYEDA SHAZEEN ALI KAZMI SYED ZULQARNANIN COMPT. POL-SC:II HUSSAIN SHAH 110051810104 2010013 MAIDA FAISAL FAISAL TABSUM COMPT. EDU:II 110051810105 2010014 MUBEEN ALTAF MUHAMMAD ALTAF PASS 518 110051810106 2010015 BISMEEN BIBI AWWAL MARJAN COMPT. ENG:I EDU:II 110051810107 2010016 ALMAS AKHTAR SHOUKAT ALI PASS 441 110051810109 2010017 UJALA AROOJ TARIQ IQBAL PASS 465 2 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc/B.Com. ANNUAL EXAMINATION 2020 (Part-II) Reg. No. Roll No. Name Father Name Status Marks Remarks 110051810110 2010018 SAWEERA ABID ABID HUSAIN COMPT. -

List of Bronze Medal Winners

LIST OF BRONZE MEDAL WINNERS FIRST POSITION IN INSTITUTION S. NO. ROLL NO. STUDENT NAME FATHER NAME CLASS INSTITUTION CITY/DISTRICT AAIMAH AHMED 1 18-47-20594-1-002-E IRFAN AHMED SUALEH 1 THE CITY NURSERY JHANG SUALEH 2 18-42-00739-1-014-E AAMINA HABIB HABIB QASIM 1 THE CITY SCHOOL JUNIOR LAHORE AL A'LA SCHOOL OF 3 18-42-20387-1-003-E AAMNA FAISAL FAISAL RIAZ 1 CONTEMPORARY AND LAHORE ISLAMIC STUDIES AANIYA AAMER 4 18-992-20490-1-003-E AAMER BHATTI 1 THE CITY NURSERY ABBOTTABAD BHATTI 5 18-051-00241-1-004-E AAYAN MASROOR TIPU MASROOR 1 ROOTS MILLENNIUM SCHOOL ISLAMABAD 6 18-544-20506-1-001-E ABBIHA MUNTAHA NISAR AHMAD 1 WINNINGTON SCHOOL JHELUM BLOOMFIELD HALL PREPS 7 18-61-00831-1-001-E ABDUL AHAD GARDEZI AHMAD NAWAZ GARDEZI 1 MULTAN AND JUNIOR SCHOOL ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 8 18-52-00546-1-069-E ABDUL AZIZ MUHAMMAD QASIM 1 SIALKOT JUNIOR CAMPUS 9 18-55-00222-1-011-E ABDUL AZIZ HAROON MUHAMMAD HAROON 1 THE NOOR SCHOOL GUJRANWALA THE CITY SCHOOL LIAQUAT 10 18-022-00518-1-001-E ABDUL HADI NASIR KHAN 1 HYDERABAD CAMPUS ALLIED SCHOOL 11 18-62-00468-1-009-E ABDUL HADI MUHAMMAD SHAKIR 1 BAHAWALPUR PRIMARY BAHAWALPUR CAMPUS ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 12 18-62-20346-1-008-E ABDUL KABEER HADI KHURRAM SHAHZAD 1 BAHAWALPUR MIDDLE BAHAWALPUR CANTT ABDUL MOIZ BIN MALIK RASHID THE CITY SCHOOL ATTOCK 13 18-57-00554-1-003-E 1 ATTOCK RASHID MEHMOOD CAMPUS AIR FOUNDATION SCHOOL 14 18-51-00538-1-004-E ABDUL RAFAY ABDUL HANAN ABBASSI 1 RAWALPINDI SYSTEM HARLEY CAMPUS AGA KHAN SCHOOL 15 18-021-00714-1-002-E ABDUL REHMAN MUHAMMAD IQBAL 1 KARACHI KHARADHAR ALLIED SCHOOL -

List of Mbbs Graduates for the Year 1997

KING EDWARD MEDICAL UNIVERSITY, LAHORE LIST OF MBBS GRADATES 1865 – 1996 1865 1873 65. Jallal Oddeen 1. John Andrews 31. Thakur Das 2. Brij Lal Ghose 32. Ghulam Nabi 1878 3. Cheytun Shah 33. Nihal Singh 66. Jagandro Nath Mukerji 4. Radha Kishan 34. Ganga Singh 67. Bishan Das 5. Muhammad Ali 35. Ammel Shah 68. Hira Lal 6. Muhammad Hussain 36. Brij Lal 69. Bhagat Ram 7. Sahib Ditta 37. Dari Mal 70. Atar Chand 8. Bhowani Das 38. Fazi Qodeen 71. Nathu Mal 9. Jaswant Roy 39. Sobha Ram 72. Kishan Chandra 10. Haran Chander Banerji 73. Duni Chand Raj 1874 74. Ata Muhammad 1868 40. Sobhan Ali 75. Charan Singh 76. Manohar Parshad 11. Fateh Singh 41. Jowahir Singh 12. Natha Mal 42. Lachman Das 1879 13. Ram Rich Pall 43. Dooni Chand 14. Bhagwan Das 44. Kali Nath Roy 77. Sada Nand 15. Mul Chand 45. Booray Khan 78. Mohandro Nath Ohdidar 16. Mehtab singh 46. Jodh Singh 79. Jai Singh 47. Munna Lal 80. Khazan Chand 48. Mehr Chand 81. Dowlat Ram 1869 49. Jowala Sahai 82. Jai Krishan Das 17. Taboo Singh 50. Gangi Ram 83. Perama Nand 18. Utum Singh 52. Devi Datta 84. Ralia Singh 19. Chany Mal 85. Jagan Nath 20. Esur Das 1875 86. Manohar Lal 21. Chunnoo Lal 53. Ram Kishan 87. Jawala Prasad 54. Kashi Ram 1870 55. Alla Ditta 1880 22. Gokal Chand 56. Bhagat Ram 88. Rasray Bhatacharji 57. Gobind Ram 89. Hira Lal Chatterji 90. Iktadar-ud-Din 1871 1876 91. Nanak Chand 23. Urjan Das 58.