1 in the Matter of a Complaint Under the Clergy Discipline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Novembre 2012 Nouveautés – New Arrivals November 2012

Novembre 2012 Nouveautés – New Arrivals November 2012 ISBN: 9781551119342 (pbk.) ISBN: 155111934X (pbk.) Auteur: Daly, Chris. Titre: An introduction to philosophical methods / Chris Daly. Éditeur: Peterborough, Ont. : Broadview Press, c2010. Desc. matérielle: 257 p. ; 23 cm. Collection: (Broadview guides to philosophy.) Note bibliogr.: Includes bibliographical references (p. 223-247) and index. B 53 D34 2010 ISBN: 9780813344485 (pbk. : alk. paper) $50.00 ISBN: 0813344484 (pbk. : alk. paper) Auteur: Boylan, Michael, 1952- Titre: Philosophy : an innovative introduction : fictive narrative, primary texts, and responsive writing / Michael Boylan, Charles Johnson. Éditeur: Boulder, CO : Westview Press, c2010. Desc. matérielle: xxii, 344 p. ; 24 cm. Note bibliogr.: Includes bibliographical references and index. B 74 B69 2010 ISBN: 9783034311311 (pbk.) $108.00 ISBN: 3034311311 (pbk.) Titre: Understanding human experience : reason and faith / Francesco Botturi (ed.). Éditeur: Bern ; New York : P. Lang, c2012. Desc. matérielle: 197 p. ; 23 cm. Note bibliogr.: Includes bibliographical references. B 105 E9U54 2012 ISBN: 9782706709104 (br) ISBN: 2706709103 (br) Auteur: Held, Klaus, 1936- Titre: Voyage au pays des philosophes : rendez-vous chez Platon / Klaus Held ; traduction de l'allemand par Robert Kremer et Marie-Lys Wilwerth-Guitard. Éditeur: Paris : Salvator, 2012. Desc. matérielle: 573 p. : ill., cartes ; 19 cm. Note générale: Traduction de: Treffpunkt Platon. Note générale: Première éd.: 1990. Note bibliogr.: Comprend des références bibliographiques (p. 547-558) et des index. B 173 H45T74F7 2012 ISBN: 9780826457530 (hbk.) ISBN: 0826457533 (hbk.) Auteur: Adluri, Vishwa. Titre: Parmenides, Plato, and mortal philosophy : return from transcendence / Vishwa Adluri. Éditeur: London ; New York : Continuum, c2011. Desc. matérielle: xv, 212 p. ; 24 cm. Collection: (Continuum studies in ancient philosophy) Note bibliogr.: Includes bibliographical references (p. -

The Empty Tomb

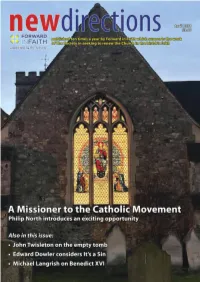

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

St Stephen's House 2 0 2 0 / 2 0

2020 / 2021 ST STEPHEN’S HOUSE NEWS 2 St Stephen’s House News 2020 / 2021 2020 / 2021 St Stephen’s House News 3 2020 / 2021 PRINCIPAL’S ST STEPHEN’S HOUSE CONTENTS NEWS WELCOME elcome to the latest edition of the NEWS WCollege Newsletter, in what has proved to be the most extraordinary year On the cover for us – as for most people – since the In recognition and Second World War. In March we were able thanks to our alumni for their many and to welcome the Chancellor of the University varied contributions of Oxford, Lord Patten of Barnes, to the Archbishop Stephen Cottrell Covid-19’s unsung alumni to society during (p13) heroes (p10) Covid-19. celebrations on Edward King Day, which were particularly important for us this year News ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 as we marked fifty years of our formal The College during Covid-19 ......................................................................................................................... 5 association with the University of Oxford, and A new VP in the House .................................................................................................................................. 8 forty years of our occupation of our current Alumni: celebrating the unsung heroes of Covid-19 ................................................................................... 10 Michael Dixon & Lydia Jones Joachim Delia Hugo Weaver buildings. Little did we know -

TV Presenter Launches Lily Appeal

E I D S Morality in the IN financial world explored E6 THE SUNDAY, MARCH 10, 2013 No: 6167 www.churchnewspaper.com PRICE £1.35 1,70j US$2.20 CHURCH OF ENGLAND THE ORIGINAL CHURCH NEWSPAPER ESTABLISHED IN 1828 NEWSPAPER Wakefield rebuffs plan for merger of dioceses FOLLOWING the failure of the Diocese of changed by the proposal. Blackburn will burn has voted. He can allow the plan to go Speaking after votes, Professor Michael Wakefield to approve the plan to replace receive six parishes and Sheffield will to General Synod if he is satisfied that the Clark, chair of the commission that pro- three Yorkshire dioceses with one it falls to receive two parishes if the plan goes ahead. interest of the diocese withholding consent duced the plan said: “It is good to know that the Archbishop of York to decide whether Sheffield Diocese has already signified is so small that it should not prevent the the dioceses of Bradford and Ripon and the proposal should go to General Synod, its agreement and Blackburn Diocese is scheme being referred to General Synod or Leeds support the Commission’s propos- possibly in July. due to vote on 13 April. if he feels there are wider factors affecting als. Looking at the voting in Wakefield, In voting last Saturday both the Diocese The Archbishop of York will not be able the Province or the Church of England as a there is significant support there although of Ripon and Leeds and the Diocese of to announce his decision until after Black- whole that need to be considered. -

'This Is a Very Special Day'

PAGE 2 PAGE 11 PAGE 16 Trip to game Women’s creations Priest cycles for a hit with fans grace churches environment TheTHE NEWSPAPER OF THE DIOCESE OF TORONTO A A SECTION OF THE ANGnLICAN JOURNAL g l www.tiorontoc.anglican.ca SUMn MER ISSUE, 2013 ‘This is a very special day’ One of the high points of the Hundreds service for her was seeing him in his mitre and chasuble. “I couldn’t believe it. I don’t know attend what to call him now. For me, he’ll always be Father Peter.” The Rev. Canon Stephen Fields, consecration the incumbent of Holy Trinity, Thornhill, said he was “over - BY STUART MANN whelmed” by the occasion. Bish - op Fenty had been his parish VALERIE Davis of St. Hugh and St. priest in Barbados in 1977, and Edmund, Mississauga, was lined they have been close friends ever up outside St. James Cathedral in since. Toronto at 7:30 a.m. on June 22— “Personally, this is fulfilling,” a full three hours before the start said Canon Fields. “I think the of Bishop Peter Fenty’s consecra - church here has made a very im - tion service. portant statement: that we affirm Ms. Davis was one of hundreds all peoples; whatever your back - of people who arrived early to get ground or culture, we are a seat for one of the most antici - church.” pated services of the year. Before In a sign of their affection for the doors of the church opened at Bishop Fenty, many people waited 9 a.m., the lineup stretched half- for up to an hour after the service way down the block. -

Thenews You Have Called Your Church Into Being in Your Love and Strengthened Us for APRIL 2021 Your Service

A Prayer for ‘Living Christ’s Story’ God our loving Father, TheNews you have called your Church into being in your love and strengthened us for APRIL 2021 your service. Inside this month: Guide and inspire us as we seek to re-shape our approach to mission and Thanksgiving for Jabs! ministry in our diocese; ...Which means that we may be a joyful Church of missionary disciples, As the government's vaccination programme rolls ‘God saves’: one in heart and mind; for the sake of your kingdom, out across the country and protects a growing Archbishop Stephen through Jesus Christ our Lord, number of people from the COVID coronavirus P2 who is alive and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, that has made life so difficult for the last year, why one God, now and for ever. not take the opportunity to offer thanks to God for Jonny Amen. www.dioceseofyork.org.uk/living-christs-story your 'jab' in a practical way as well as in prayer? Hedges—new face at Christian Aid Stepping Up works with some P3 of the poorest Prayer and Challenge: remembering Sarah Everard and most vulner- Farewell Bishop The Bishop of Selby, the Rt Revd Dr able communities Humphrey— across the world, former Bishop John Thomson, has spoken about the Merciful God, where there may of Selby dies death of York-born Sarah Everard hear the cries of our grief, be little hope of a P4 and public response to it. for you know the anguish of our vaccine rollout. "Like many others I have been hearts. -

Apr14nn:Layout 1.Qxd

Niftynotes news & information from the Diocese www.southwell.anglican.org APRIL 2014 Compiled by Nicola Mellors email: [email protected] Lent and Easter - The Journey The Very Revd John Guille, Dean be. For Christians, for example, fulfilled. We shall awake and of Southwell Minster writes: keeping Lent as a time of find it, after all, true." (Quotation preparation for Easter is a from Adam’s Dream-Mowbray count it a great privilege to be reminder that even when we are 2007). able to share a few thoughts enjoying the comfort and security with you as we continue to I of an advanced civilisation, I wish you all a joyous and make our journey through Lent Blessed Easter. and our final preparations for the celebration of Easter. I also look Christ is risen-Allelujah! forward to sharing with the John Clergy and Readers of our Diocese in the service in the Easter Minster when we re-affirm our At a turn of the head bent intent commitment to Ministry on the on a task, Wednesday in Holy Week at ripple of light, hem of his 7.30pm. It is also lovely when we garment only, are supported by members of our or a lift of the heart suddenly less parishes at this service as well. lonely As we approach Holy week and is all the Easter evidence I ask (Bishop J. V.Taylor) Easter I find these words written by Keith Jones- until recently Dean of York very helpful with which satisfies our wants in ways particular reference to the theme unimaginable to previous In this month’s issue: of journey. -

Diocese of Chichester Opening Statement

THE DIOCESE OF CHICHESTER OPENING STATEMENT BY COUNSEL TO THE INQUIRY OPENING REMARKS 1. Good Morning, Chair and Panel. I am Ms. Fiona Scolding, lead counsel to the Anglican investigation . Next to me sits Ms. Nikita McNeill and Ms. Lara McCaffrey , junior counsel to the Anglican investigation. Today we begin the first substantive hearing into the institutional response of the Anglican Church to allegations of child sexual abuse. The Anglican investigation is just one of thirteen so far launched by the statutory Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse established by the Home Secretary in March 2015, offering an unprecedented opportunity to examine the extent to which institutions and organisations in England and Wales have been able to respond appropriately to allegations of abuse. 2. This hearing focuses upon the response of the Diocese of Chichester to allegations made to it about various individuals – both clergy and volunteers over the past thirty years. Some of the abuse you will hear about occurred during the 1950’s and 1960’s: some of it is much more recent in origin. A series of allegations came to light from the late 1990’s onwards and then engulfed the Diocese of Chichester in the first decade of the 21 st century. The role of the hearing is to examine what happened and what that shows about the ability of the Anglican Church to protect children in the past. It is also to ask 1 about its ability to learn lessons and implement change as a result of learning from the mistakes which it has acknowledged that it has made. -

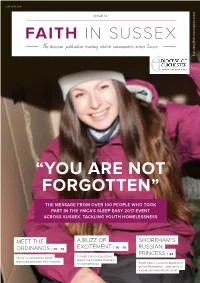

“You Are Not Forgotten”

ISSN 2056-3310 www.chichester.anglican.org ISSUE 14 “YOU ARE NOT FORGOTTEN” THE MESSAGE FROM OVER 100 PEOPLE WHO TOOK PART IN THE YMCA’S SLEEP EASY 2017 EVENT ACROSS SUSSEX, TACKLING YOUTH HOMELESSNESS MEET THE A BUZZ OF SHOREHAM’S ORDINANDS / 10 - 13 EXCITEMENT / 16 - 19 RUSSIAN PRINCESS / 34 12 men and women to be Church schools positive ordained deacons this summer response to bible-themed art competition Read how a staunch opponent of the Bolshevics now rests in a quiet Sussex churchyard Avoid a wrong turn with your care planning. Get on the right track with Carewise. How am I going to pay for my care? How much Will I have might it to sell my cost me? h ouse? l Help to consider What can care options l Money advice and I afford? benefits check l Comprehensive care services information l Approved care fee specialists | 01243 642121 • [email protected] www.westsussexconnecttosupport.org/carewise WS31786 02.107 WS31786 ISSUE 14 3 WELCOME As we move into the summer of 2017 there are two events that will unfold. The first is the General Election; the second is the novena of prayer, Thy Kingdom Come, that leads us from Ascension Day to Pentecost. These two events are closely linked for us as Christians individually and corporately as the Church. As Christians, we have an important contribution to make in the election. First, it is the assertion that having a vote is a statement of the mutual recognition of dignity in our society. In this respect, we are equal, each of us having one vote. -

Walsingham Festival at Westminster Abbey Page 10

Assumptiontide 2019 | Issue 164 The magazine of the Anglican Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham Walsingham Festival at Westminster Abbey Page 10 National Pilgrimage The Walsingham Bible Priests Associate Serving Book Review: Walsingham in the Armed Forces – Pilgrims & Pilgrimage Page 4 Page 6 Page 12 Page 17 The Priest Administrator’s Letter Henry III (six times). Edward I (thirteen times). Edward II (twice). Mary’s life and Then Edward III, Richard II, the Henry’s IV, V, VI, VII and finally, as we all know, Henry VIII. vocation perfectly mirror the values All these monarchs, often with their queens and royal children, came as pilgrims to Walsingham. It is an indication of the of the Gospel importance and fame of Our Lady’s Shrine before its destruction, taught by Jesus (tragically at royal hands), as well as of the influence of the Christian in the Beatitudes. faith in the lives of England’s rulers and in the history of our nation. Whenever we look Many of the monarchs who prayed in England’s Nazareth now at the beautiful lie in their royal tombs in Westminster Abbey, surrounding the Shrine of S. Edward the Confessor. As the Pilgrim Hymn reminds Image of Our Lady us, it was during Edward’s reign that the Shrine of Our Lady of of Walsingham, we Walsingham was founded. I dare to imagine that he and all those former royal pilgrims would have rejoiced to see two thousand see what the words present-day pilgrims gathered in the Abbey for the Walsingham of the Gospel mean. -

A Missioner to the Catholic Movement Philip North Introduces an Exciting New Role

ELLAND All Saints , Charles Street, HX5 0LA A Parish of the Soci - ety under the care of the Bishop of Wakefield . Serving Tradition - alists in Calderdale. Sunday Mass 9.30am, Rosary/Benediction usually last Sunday, 5pm. Mass Tuesday, Friday & Saturday, parish directory 9.30am. Canon David Burrows SSC , 01422 373184, rectorofel - [email protected] BATH Bathwick Parishes , St.Mary’s (bottom of Bathwick Hill), BROMLEY St George's Church , Bickley Sunday - 8.00am www.ellandoccasionals.blogspot.co.uk St.John's (opposite the fire station) Sunday - 9.00am Sung Mass at Low Mass, 10.30am Sung Mass. Daily Mass - Tuesday 9.30am, St.John's, 10.30am at St.Mary's 6.00pm Evening Service - 1st, Wednesday 9.30am, Holy Hour, 10am Mass Friday 9.30am, Sat - FOLKESTONE Kent , St Peter on the East Cliff A Society 3rd &5th Sunday at St.Mary's and 2nd & 4th at St.John's. Con - urday 9.30am Mass & Rosary. Fr.Richard Norman 0208 295 6411. Parish under the episcopal care of the Bishop of Richborough . tact Fr.Peter Edwards 01225 460052 or www.bathwick - Parish website: www.stgeorgebickley.co.uk Sunday: 8am Low Mass, 10.30am Solemn Mass. Evensong 6pm parishes.org.uk (followed by Benediction 1st Sunday of month). Weekday Mass: BURGH-LE-MARSH Ss Peter & Paul , (near Skegness) PE24 daily 9am, Tues 7pm, Thur 12 noon. Contact Father Mark Haldon- BEXHILL on SEA St Augustine’s , Cooden Drive, TN39 3AZ 5DY A resolution parish in the care of the Bishop of Richborough . Jones 01303 680 441 http://stpetersfolk.church Saturday: Mass at 6pm (first Mass of Sunday)Sunday: Mass at Sunday Services: 9.30am Sung Mass (& Junior Church in term e-mail :[email protected] 8am, Parish Mass with Junior Church at1 0am. -

Christingle Support of the Children’S Society of the Children’S Support / 14

ISSN 2056-3310 www.chichester.anglican.org ISSUE 12 CHRISTINGLE THIS HUGELY POPULAR EVENT TAKES PLACE IN CHURCHES AND SCHOOLS ACROSS THE DIOCESE IN SUPPORT OF THE CHILDREN’S SOCIETY BUILD YOUR CELEBRATING ‘ADMITTED AND WELCOME / 14 YEAR OF THE LICENSED, LOVED / 18 / 26 Free resources to help BIBLE 2017 AND AFFIRMED’ parishes develop welcome packs Discover ‘its rich message of New Readers speak of their hope, peace and joy for all people special day Reformation tf oor day 28 APRIL -1 MAY 2017 THE WINTER GARDEN, EASTBOURNE www.biblebythebeach.org @biblebythebeach Bible by the beach t 07958 047140 e [email protected] ISSUE 12 3 BISHOP RICHARD WRITES.. Advent 2016 (November 27) will begin the Year of the Bible, the next strand of the Diocesan Strategy. A team has been working behind the scenes for some months now, preparing materials and events, organising the Lent course and getting ready for what I hope will be an exciting year in the life of the Diocese. Many Christians find it hard to get into regular Bible reading and find bits of it difficult to understand. We hope that over the course of this year we’ll be able to face some of these difficulties and fears head on, improve our knowledge of the scriptures and how they hang together, and put the Bible at the heart of our personal discipleship. The year will be launched at Diocesan Synod on November 15th, with events throughout 2017. Do watch out for further details of these in the magazine, e-news and website. With best wishes, +Richard Lewes November 2016 ISSUE 12 5 CONTENTS NEWS